This is “Is Facebook Worth It?”, section 8.10 from the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems: A Manager's Guide (v. 1.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

8.10 Is Facebook Worth It?

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Question the $15 billion valuation so often cited by the media.

- Understand why Microsoft might be willing to offer to invest in Facebook at a higher valuation rate.

It has often been said that the first phase of the Internet was about putting information online and giving people a way to find it. The second phase of the Web is about connecting people with one another. The Web 2.0 movement is big and impactful, but is there much money in it?

While the valuations of private firms are notoriously difficult to pin down due to a lack of financial disclosure, the often-cited $15 billion valuation from the fall of 2007 Microsoft investment was rich, even when made by such a deep-pocketed firm. Using estimates at the time of the deal, if Facebook were a publicly traded company, it would have a price-to-earnings ratio of five hundred; Google’s at the time was fifty-three, and the average for the S&P 500 is historically around fifteen.

But the math behind the deal is a bit more complex than was portrayed in most press reports. The deal was also done in conjunction with an agreement that for a time let Microsoft manage the sale of Facebook’s banner ads worldwide. And Microsoft’s investment was done on the basis of preferred stock, granting the firm benefits beyond common stock, such as preference in terms of asset liquidation.B. Stone, “Facebook Aims to Extends Its Reach across Web,” New York Times, December 1, 2008. Both of these are reasons a firm would be willing to “pay more” to get in on a deal.

Another argument can be made for Microsoft purposely inflating the value of Facebook in order to discourage rival bidders. A fat valuation by Microsoft and a deal locking up ad rights makes the firm seem more expensive, less attractive, and out of reach for all but the richest and most committed suitors. Google may be the only firm that could possibly launch a credible bid, and Zuckerberg is reported to be genuinely uninterested in being absorbed by the search sovereign.F. Vogelstein, “The Great Wall of Facebook,” Wired, July 2009.

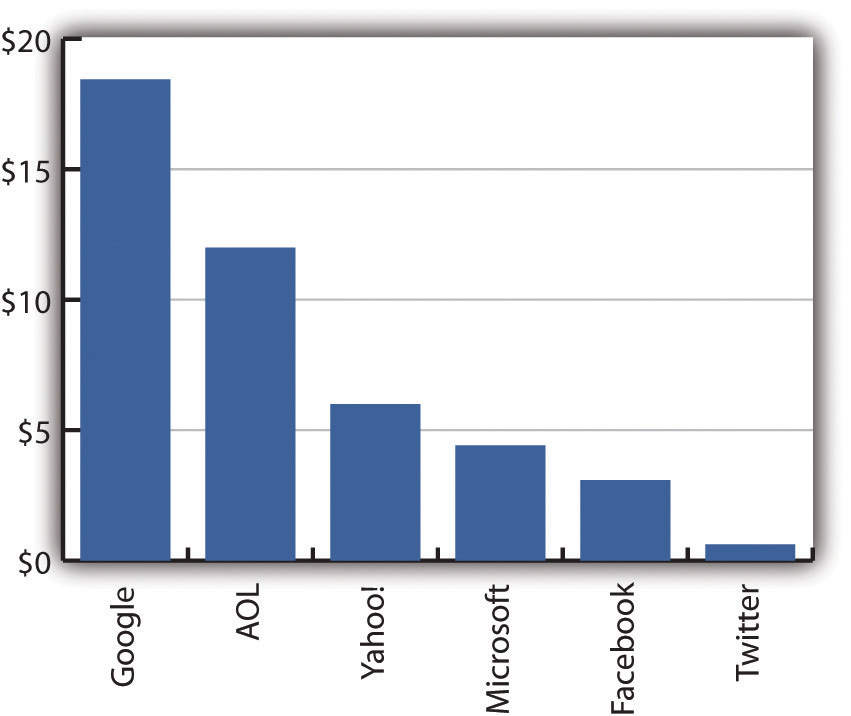

Since the fall of 2007, several others have invested private money into Facebook as well, including the Founders Fund and Li Ka-shing, the Hong Kong billionaire behind Hutchison Whampoa. Press reports and court documents suggest that these deals were done at valuations that were lower than what Microsoft accepted. In May 2009 Russian firm Digital Sky paid $200 million for 1.96 percent of the firm, a ten-billion-dollar valuation (also in preferred stock). That’s a one-third haircut off the Microsoft price, albeit without the Redmond-specific strategic benefits of the investment.D. Kirkpatrick, “Why Microsoft Isn’t Buying Facebook,” Fortune, May 9, 2008; and S. Ante, “Facebook: Friends with Money,” BusinessWeek, May 9, 2008. And as the chart in Figure 8.2 "Revenue per User (2009)" shows, Facebook still lags well behind many of its rivals in terms of revenue per user.

Figure 8.2 Revenue per User (2009)

While Facebook’s reach has grown to over half a billion visitors a month, its user base generates far less cash on a per-person basis than many rivals do.H. Blodget, “Whoops—Facebook Is Once Again Overhyped,” Business Insider, April 26, 2010.

So despite the headlines, even at the time of the Microsoft investment, Facebook was almost certainly not valued at a pure $15 billion. This isn’t to say definitively that Facebook won’t be worth $15 billion (or more) someday, but even a valuation at “just” $10 billion is a lot to pay for a then-profitless firm with estimated 2009 revenues of $500 million. Of course, raising more capital enables Zuckerberg to go on the hunt as well. Facebook investor Peter Theil confirmed the firm had already made an offer to buy Twitter (a firm which at the time had zero dollars in revenues and no discernible business model) for a cool half billion dollars.S. Ante, “Facebook’s Thiel Explains Failed Twitter Takeover,” BusinessWeek, March 1, 2009.

Much remains to be demonstrated for any valuation to hold. Facebook is new. Its models are evolving, and it has quite a bit to prove. Consider efforts to try to leverage friend networks. According to Facebook’s own research, “an average Facebook user with 500 friends actively follows the news on only forty of them, communicates with twenty, and keeps in close touch with about ten. Those with smaller networks follow even fewer.”S. Baker, “Learning and Profiting from Online Friendships,” BusinessWeek, May 21, 2009. That might not be enough critical mass to offer real, differentiable impact, and that may have been part of the motivation behind Facebook’s mishandled attempts to encourage more public data sharing. The advantages of leveraging the friend network hinge on increased sharing and trust, a challenge for a firm that has had so many high-profile privacy stumbles. There is promise. Profiling firm Rapleaf found that targeting based on actions within a friend network can increase click-through rates threefold—that’s an advantage advertisers are willing to pay for. But Facebook is still far from proving it can consistently achieve the promise of delivering valuable ad targeting.

Steve Rubel wrote the following on his Micro Persuasion blog: “The Internet amber is littered with fossilized communities that once dominated. These former stalwarts include AOL, Angelfire, theGlobe.com, GeoCities, and Tripod.” Network effects and switching cost advantages can be strong, but not necessarily insurmountable if value is seen elsewhere and if an effort becomes more fad than “must have.” Time will tell if Facebook’s competitive assets and constant innovation are enough to help it avoid the fate of those that have gone before them.

Key Takeaways

- Not all investments are created equal, and a simple calculation of investment dollars multiplied by the percentage of firm owned does not tell the whole story.

- Microsoft’s investment entitled the firm to preferred shares; it also came with advertising deal exclusivity.

- Microsoft may also benefit from offering higher valuations that discourage rivals from making acquisition bids for Facebook.

- Facebook has continued to invest capital raised in expansion, particularly in hardware and infrastructure. It has also pursued its own acquisitions, including a failed bid to acquire Twitter.

- The firm’s success will hinge on its ability to create sustainably profitable revenue opportunities. It has yet to prove that data from the friend network will be large enough and can be used in a way that is differentiably attractive to advertisers. However, some experiments in profiling and ad targeting across a friend network have shown very promising results. Firms exploiting these opportunities will need to have a deft hand in offering consumer and firm value while quelling privacy concerns.

Questions and Exercises

- Circumstances change over time. Research the current state of Facebook’s financials—how much is the firm “valued at”? How much revenue does it bring in? How profitable is it? Are these figures easy or difficult to find? Why or why not?

- Who else might want to acquire Facebook? Is it worth it at current valuation rates?

- What motivation does Microsoft have in bidding so much for Facebook?

- Do you think Facebook was wise to take funds from Digital Sky? Why or why not?

- Do you think Facebook’s friend network is large enough to be leveraged as a source of revenue in ways that are notably different than conventional pay-per-click or CPM-based advertising? Would you be excited about certain possibilities? Creeped out by some? Explain possible scenarios that might work or might fail. Justify your interpretation of these scenarios.

- So you’ve had a chance to learn about Facebook, its model, growth, outlook, strategic assets, and competitive environment. How much do you think the firm is worth? Which firms do you think it should compare with in terms of value, influence, and impact? Would you invest in Facebook?

- Which firms might make good merger partners with Facebook? Would these deals ever go through? Why or why not?