This is “The Software Cloud: Why Buy When You Can Rent?”, section 10.7 from the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems: A Manager's Guide (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

10.7 The Software Cloud: Why Buy When You Can Rent?

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Know how firms using SaaS products can dramatically lower several costs associated with their information systems.

- Know how SaaS vendors earn their money.

- Be able to list the benefits to users that accrue from using SaaS.

- Be able to list the benefits to vendors from deploying SaaS.

If open source isn’t enough of a threat to firms that sell packaged software, a new generation of products, collectively known as SaaS, claims that you can now get the bulk of your computing done through your Web browser. Don’t install software—let someone else run it for you and deliver the results over the Internet.

Software as a service (SaaS) refers to software that is made available by a third party online. You might also see the terms ASP (application service provider) or HSV (hosted software vendor) used to identify this type of offering. SaaS is potentially a very big deal. Firms using SaaS products can dramatically lower several costs associated with the care and feeding of their information systems, including software licenses, server hardware, system maintenance, and IT staff. Most SaaS firms earn money via a usage-based pricing model akin to a monthly subscription. Others offer free services that are supported by advertising, while others promote the sale of upgraded or premium versions for additional fees.

Make no mistake, SaaS is yet another direct assault on traditional software firms. The most iconic SaaS firm is Salesforce.com, an enterprise customer relationship management (CRM) provider. This “un-software” company even sports a logo featuring the word “software” crossed out, Ghostbusters-style.J. Hempel, “Salesforce Hits Its Stride,” Fortune, March 2, 2009.

Figure 10.3

The antisoftware message is evident in the logo of SaaS leader Salesforce.com.

Other enterprise-focused SaaS firms compete directly with the biggest names in software. Some of these upstarts are even backed by leading enterprise software executives. Examples include NetSuite (funded in part by Oracle’s Larry Ellison—the guy’s all over this chapter), which offers a comprehensive SaaS ERP suite; and Workday (launched by founders of Peoplesoft), which has SaaS offerings for managing human resources. Several traditional software firms have countered startups by offering SaaS efforts of their own. IBM offers a SaaS version of its Cognos business intelligence products, Oracle offers CRM On Demand, and SAP’s Business ByDesign includes a full suite of enterprise SaaS offerings. Even Microsoft has gone SaaS, with a variety of Web-based services that include CRM, Web meeting tools, collaboration, e-mail, and calendaring.

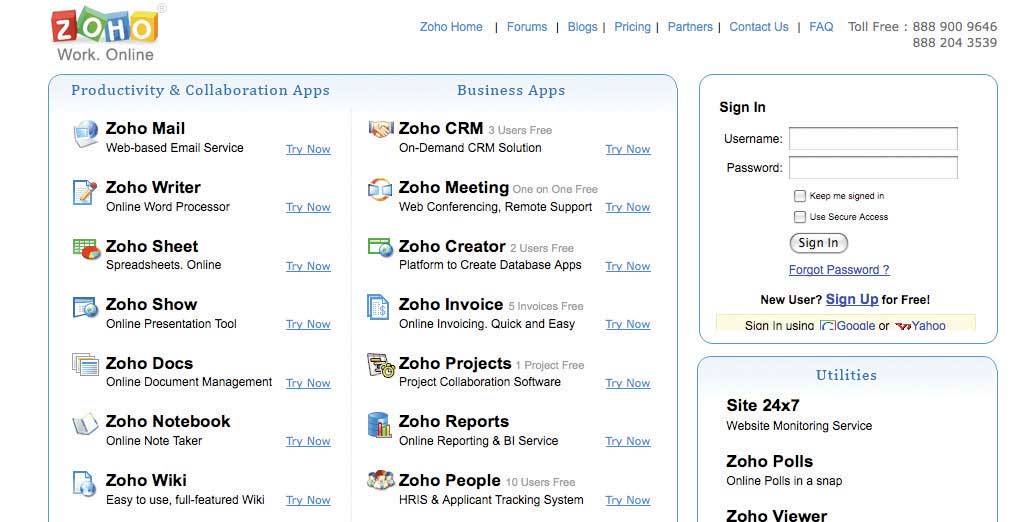

Figure 10.4

A look at Zoho’s home page shows the diversity of both desktop and enterprise offerings from this SaaS upstart. Note that the firm makes it services available through browsers, phones, and even Facebook.

SaaS is also taking on desktop applications. Intuit has online versions of its QuickBooks, TurboTax, and Quicken finance software. Adobe has an online version of Photoshop. Google and Zoho offer office suites that compete with desktop alternatives, prompting Microsoft’s own introduction of an online version of Office. And if you store photos on Flickr or Picassa instead of your PC’s hard drive, then you’re using SaaS, too.

The Benefits of SaaS

Firms can potentially save big using SaaS. Organizations that adopt SaaS forgo the large upfront costs of buying and installing software packages. For large enterprises, the cost to license, install, and configure products like ERP and CRM systems can easily run into the hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars. And these costs are rarely a one time fee. Additional costs like annual maintenance contracts have also been rising as rivals fail or get bought up. Less competition among traditional firms recently allowed Oracle and SAP to raise maintenance fees to as much as 20 percent.Sarah Lacy, “On-Demand Computing: A Brutal Slog,” BusinessWeek, July 18, 2008.

Firms that adopt SaaS don’t just save on software and hardware, either. There’s also the added cost for the IT staff needed to run these systems. Forrester Research estimates that SaaS can bring cost savings of 25 to 60 percent if all these costs are factored in.J. Quittner, “How SaaS Helps Cut Small Business Costs,” BusinessWeek, December 5, 2008.

There are also accounting and corporate finance implications for SaaS. Firms that adopt software as a service never actually buy a system’s software and hardware, so these systems become a variable operating expense. This flexibility helps mitigate the financial risks associated with making a large capital investment in information systems. For example, if a firm pays Salesforce.com sixty-five dollars per month per user for its CRM software, it can reduce payments during a slow season with a smaller staff, or pay more during heavy months when a firm might employ temporary workers. At these rates, SaaS not only looks good to large firms, it makes very sophisticated technology available to smaller firms that otherwise wouldn’t be able to afford expensive systems, let alone the IT staff and hardware required to run them.

In addition to cost benefits, SaaS offerings also provide the advantage of being highly scalable. This feature is important because many organizations operate in environments prone to wide variance in usage. Some firms might expect systems to be particularly busy during tax time or the period around quarterly financial reporting deadlines, while others might have their heaviest system loads around a holiday season. A music label might see spikes when an artist drops a new album. Using conventional software, an organization would have to buy enough computing capacity to ensure that it could handle its heaviest anticipated workload. But sometimes these loads are difficult to predict, and if the difference between high workloads and average use is great, a lot of that expensive computer hardware will spend most of its time doing nothing. In SaaS, however, the vendor is responsible for ensuring that systems meet demand fluctuation. Vendors frequently sign a service level agreement (SLA)A negotiated agreement between the customer and the vendor. The SLA may specify the levels of availability, serviceability, performance, operation, or other commitment requirements. with their customers to ensure a guaranteed uptime and define their ability to meet demand spikes.

When looking at the benefits of SaaS, also consider the potential for higher quality and service levels. SaaS firms benefit from economies of scale that not only lower software and hardware costs, but also potentially boost quality. The volume of customers and diversity of their experiences means that an established SaaS vendor is most likely an expert in dealing with all sorts of critical computing issues. SaaS firms handle backups, instantly deploy upgrades and bug fixes, and deal with the continual burden of security maintenance—all costly tasks that must be performed regularly and with care, although each offers little strategic value to firms that perform these functions themselves in-house. The breadth of a SaaS vendor’s customer base typically pushes the firm to evaluate and address new technologies as they emerge, like quickly offering accessibility from mobile platforms like the Blackberry and iPhone. For all but the savviest of IT shops, an established SaaS vendor can likely leverage its scale and experience to provide better, cheaper, more reliable standard information systems than individual companies typically can.

Software developers who choose to operate as SaaS providers also realize benefits. While a packaged software company like SAP must support multiple versions of its software to accommodate operating systems like Windows, Linux, and various flavors of Unix, an SaaS provider develops, tests, deploys, and supports just one version of the software executing on its own servers.

An argument might also be made that SaaS vendors are more attuned to customer needs. Since SaaS firms run a customer’s systems on their own hardware, they have a tighter feedback loop in understanding how products are used (and why they fail)—potentially accelerating their ability to enhance their offerings. And once made, enhancements or fixes are immediately available to customers the next time they log in.

SaaS applications also impact distribution costs and capacity. As much as 30 percent of the price of traditional desktop software is tied to the cost of distribution—pressing CD-ROMs, packaging them in boxes, and shipping them to retail outlets.M. Drummond, “The End of Software as We Know It,” Fortune, November 19, 2001. Going direct to consumers can cut out the middleman, so vendors can charge less or capture profits that they might otherwise share with a store or other distributor. Going direct also means that SaaS applications are available anywhere someone has an Internet connection, making them truly global applications. This feature has allowed many SaaS firms to address highly specialized markets (sometimes called vertical nichesSometimes referred to as vertical markets. Products and services designed to target a specific industry (e.g., pharmaceutical, legal, apparel retail).). For example, the Internet allows a company writing specialized legal software, for example, or a custom package for the pharmaceutical industry, to have a national deployment footprint from day one. Vendors of desktop applications that go SaaS benefit from this kind of distribution, too.

Finally, SaaS allows a vendor to counter the vexing and costly problem of software piracy. It’s just about impossible to make an executable, illegal copy of a subscription service that runs on a SaaS provider’s hardware.

Gaming in Flux: Is There a Future in Free?

PC game makers are in a particularly tough spot. Development costs are growing as games become more sophisticated. But profits are plummeting as firms face rampant piracy, a growing market for used game sales, and lower sales from rental options from firms like Blockbuster and GameFly. To combat these trends, Electronic Arts (EA) has begun to experiment with a radical alternative to PC game sales—give the base version of the product away for free and make money by selling additional features.

The firm started with the Korean version of its popular FIFA soccer game. Koreans are crazy for the world’s most popular sport; their nation even cohosted the World Cup in 2002. But piracy was killing EA’s sales in Korea. To combat the problem, EA created a free, online version of FIFA that let fans pay for additional features and upgrades, such as new uniforms for their virtual teams, or performance-enhancing add-ons. Each enhancement only costs about one dollar and fifty cents, but the move to a model based on these so-called “microtransactionsSmall payments, typically paid for product or services purchased online. Gaming firms, news, music, and other media efforts have all experimented with microtransactions, albeit with varying degrees of success.” has brought in big earnings. During the first two years that the microtransaction-based Korean FIFA game was available, EA raked in roughly one million dollars a month. The two-year, twenty-four-million-dollar take was twice the sales record for EA’s original FIFA game.

Asian markets have been particularly receptive to microtransactions—this revenue model makes up a whopping 50 percent of the region’s gaming revenues. But whether this model can spread to other parts of the world remains to be seen. The firm’s first free, microtransaction offering outside of Korea leverages EA’s popular Battlefield franchise. Battlefield Heroes sports lower quality, more cartoon-like graphics than EA’s conventional Battlefield offerings, but it will be offered free online. Lest someone think they can rise to the top of player rankings by buying the best military hardware for their virtual armies, EA offers a sophisticated matching engine, pitting players with similar abilities and add-ons against one another.J. Schenker, “EA Leaps into Free Video Games,” BusinessWeek, January 22, 2008.

Players of the first versions of Battlefield Heroes and FIFA Online needed to download software to their PC. But the startup World Golf Tour shows how increasingly sophisticated games can execute within a browser, SaaS-style. WGT doesn’t have quite the graphics sophistication of the dominant desktop golf game (EA’s Tiger Woods PGA Golf), but the free, ad-supported offering is surprisingly detailed. Buddies can meet up online for a virtual foursome, played on high-resolution representations of the world’s elite courses stitched together from fly-over photographs taken as part of game development. World Golf Tour is ad-supported. The firm hopes that advertisers will covet access to the high-income office workers likely to favor a quick virtual golf game to break up their workday. Zynga’s Farmville, an app game for Facebook, combines both models. Free online, but offering added features purchased in micropayment-sized chunks, Farmville made half a million dollars in three days, just by selling five-dollar virtual sweet potatoes.D. MacMillan, P. Burrows, and S. Ante, “Inside the App Economy,” BusinessWeek, October 22, 2009. FIFA Online, Battlefield Heroes, World Golf Tour, and Farmville all show that the conventional models of gaming software are just as much in flux as those facing business and productivity packages.

Key Takeaways

-

SaaS firms may offer their clients several benefits including the following:

- lower costs by eliminating or reducing software, hardware, maintenance, and staff expenses.

- financial risk mitigation since startup costs are so low.

- potentially faster deployment times compared with installed packaged software or systems developed in-house.

- costs are a variable operating expense rather than a large, fixed capital expense.

- scalable systems make it easier for firms to ramp up during periods of unexpectedly high system use.

- higher quality and service levels through instantly available upgrades, vendor scale economies, and expertise gained across its entire client base.

- remote access and availability—most SaaS offerings are accessed through any Web browser, and often even by phone or other mobile device.

-

Vendors of SaaS products benefit by:

- limiting development to a single platform, instead of having to create versions for different operating systems.

- tighter feedback loop with clients, helping fuel innovation and responsiveness.

- ability to instantly deploy bug fixes and product enhancements to all users.

- lower distribution costs.

- accessibility to anyone with an Internet connection.

- greatly reduces software piracy.

- Microtransactions and ad-supported gaming present alternatives to conventional purchased video games. Firms leveraging these models potentially benefit from a host of SaaS advantages, including direct-to-consumer distribution, instant upgrades, continued revenue streams rather than one-time purchase payments, and a method for combating piracy.

Questions and Exercises

- Firms that buy conventional enterprise software spend money buying software and hardware. What additional and ongoing expenses are required as part of the “care and feeding” of enterprise applications?

- In what ways can firms using SaaS products dramatically lower costs associated with their information systems?

- How do SaaS vendors earn their money?

- Give examples of enterprise-focused SaaS vendors and their products. Visit the Web sites of the firms that offer these services. Which firms are listed as clients? Does there appear to be a particular type of firm that uses its services, or are client firms broadly represented?

- Give examples of desktop-focused SaaS vendors and their products. If some of these are free, try them out and compare them to desktop alternatives you may have used. Be prepared to share your experiences with your class.

- List the cost-related benefits to users that accrue from using SaaS.

- List the benefits other than cost-related that accrue to users from using SaaS.

- List the benefits realized by vendors that offer SaaS services instead of conventional software.

- Microtransactions have been tried in many contexts, but have often failed. Can you think of contexts where microtransactions don’t work well? Are there contexts where you have paid (or would be wiling to pay) for products and services via microtransactions? What do you suppose are the major barriers to the broader acceptance of microtransactions? Do struggles have more to do with technology, consumer attitudes, or both?

- Search online to find free and microtransaction-based games. What do you think of these efforts? What kind of gamers do these efforts appeal to? See if you can investigate whether there are examples of particularly successful offerings, or efforts that have failed. What’s the reason behind the success or failure of the efforts that you’ve investigated?