This is “Google: Search, Online Advertising, and Beyond…”, chapter 8 from the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems: A Manager's Guide (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 8 Google: Search, Online Advertising, and Beyond…

8.1 Introduction

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand the extent of Google’s rapid rise and its size and influence when compared with others in the media industry.

- Recognize the shift away from traditional advertising media to Internet advertising.

- Gain insight into the uniqueness and appeal of Google’s corporate culture.

Google has been called a one-trick pony,C. Li, “Why Google’s One-Trick Pony Struggles to Learn New Tricks,” Harvard Business Publishing, May 2009. but as tricks go, it’s got an exquisite one. Google’s “trick” is matchmaking—pairing Internet surfers with advertisers and taking a cut along the way. This cut is substantial—over twenty-one billion dollars in 2008. In fact, as Wired’s Steve Levy puts it, Google’s matchmaking capabilities may represent “the most successful business idea in history.”S. Levy, “The Secrets of Googlenomics,” Wired, June 2009. For perspective, consider that as a ten-year-old firm, and one that had been public for less than five years, Google had already grown to earn more annual advertising dollars than any U.S. media company. No television network, no magazine group, no newspaper chain brings in more ad bucks than Google. And none is more profitable. While Google’s stated mission is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful,” advertising drives profits and lets the firm offer most of its services for free.

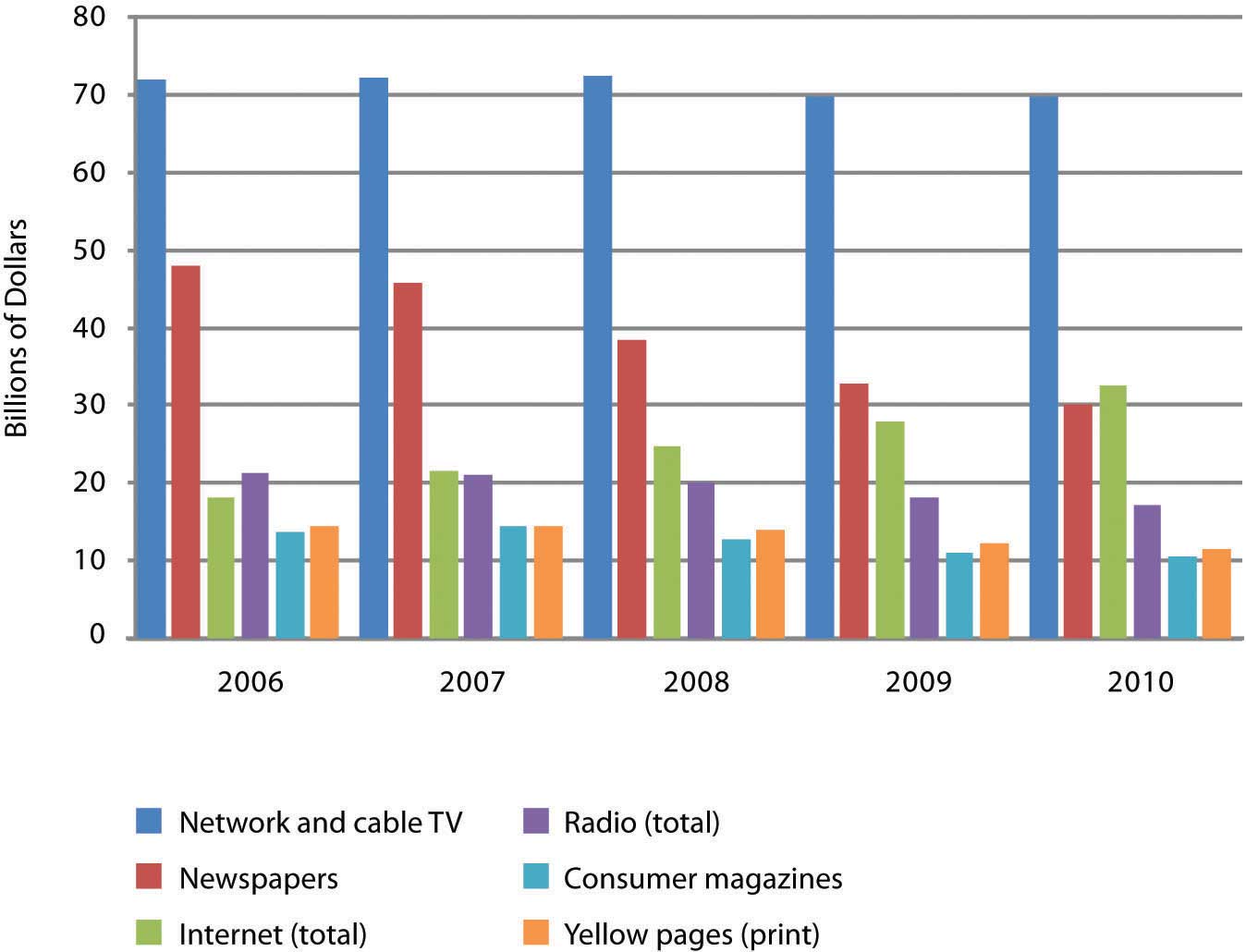

Figure 8.1 U.S. Advertising Spending (by selected media)

Online advertising represents the only advertising category trending with positive growth. Figures for 2009 and beyond are estimates.

Source: Data retrieved via eMarketer.com.

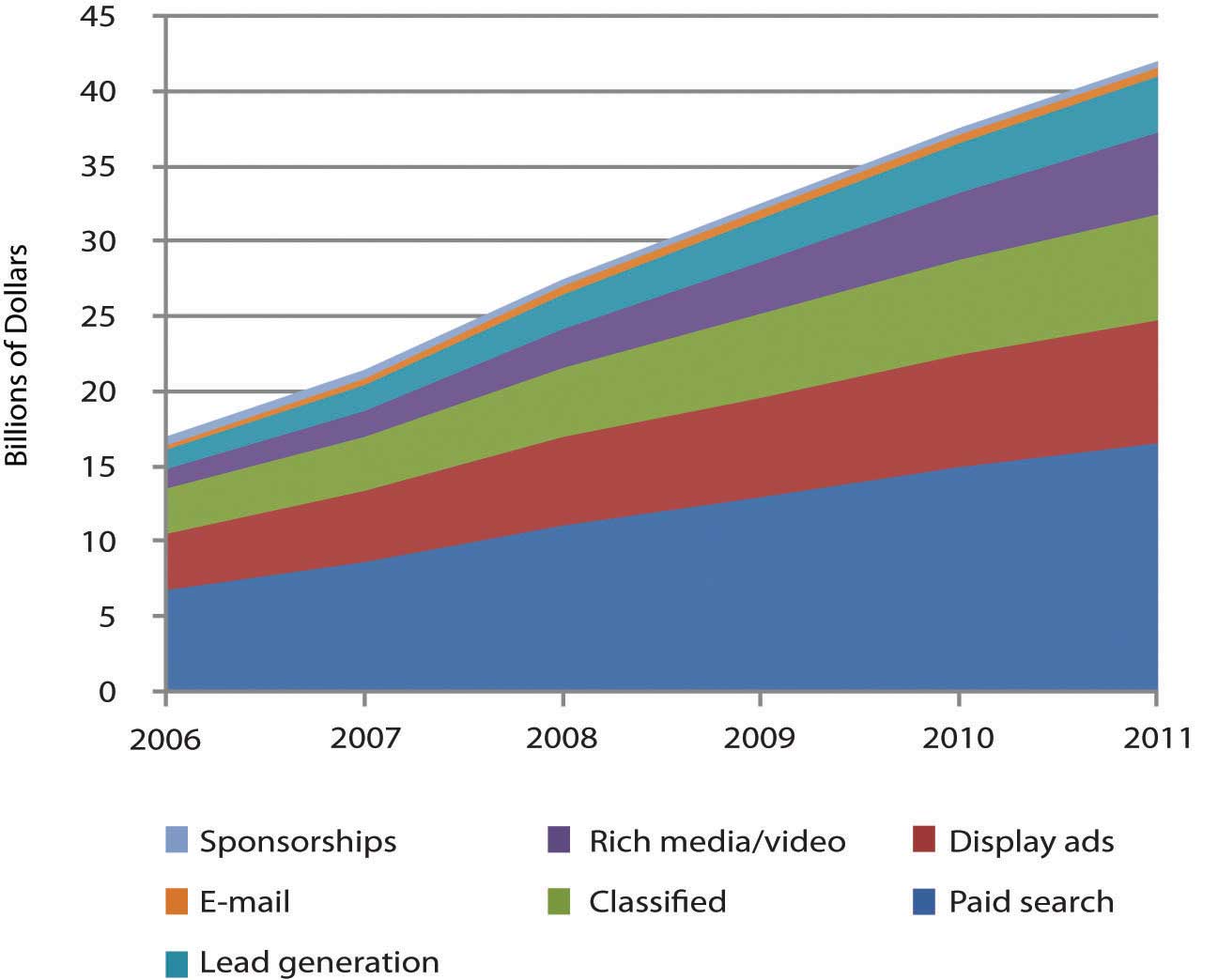

Figure 8.2 U.S. Online Ad Spending (by format)

Search captures the most online ad dollars, and Google dominates search advertising. Figures for 2009 and beyond are estimates.

Source: Data retrieved via eMarketer.com.

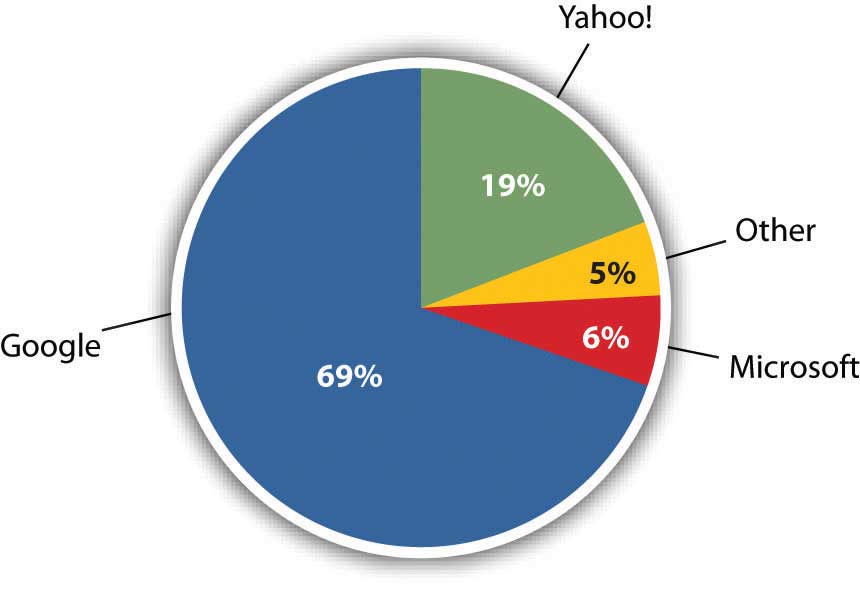

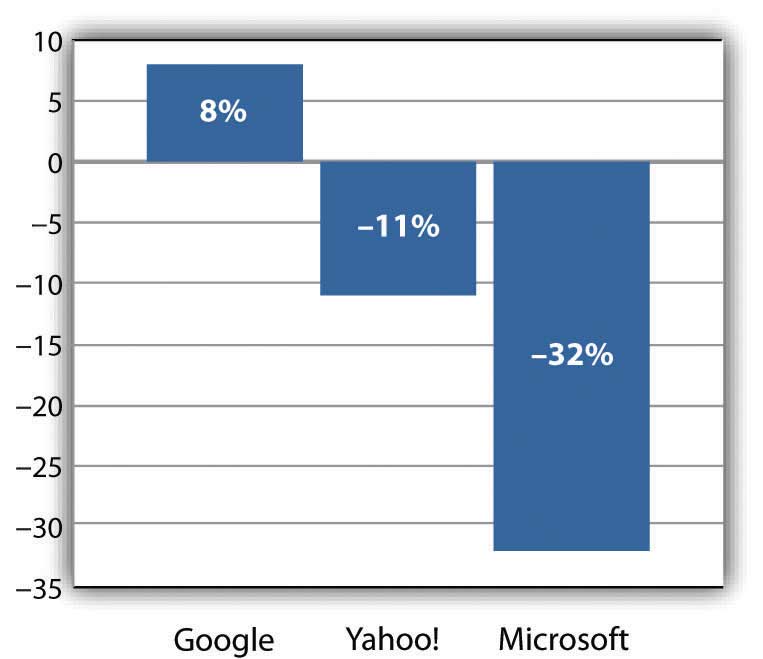

As more people spend more time online, advertisers are shifting spending away from old channels to the Internet; and Google is swallowing the lion’s share of this funds transfer.J. Pontin, “But Who’s Counting?” Technology Review, March/April 2009. By some estimates Google has 76 percent of the search advertising business.C. Sherman, “Report: Google Leads U.S. Search Advertising Market With 76% Market Share,” Search Engine Land, January 20, 2009. Add to that Google’s lucrative AdSense network that serves ads to sites ranging from small time bloggers to the New York Times, plus markets served by Google’s acquisition of display ad leader DoubleClick, and the firm controls in the neighborhood of 70 percent of all online advertising dollars.L. Baker, “Google Now Controls 69% of Online Advertising Market,” Search Engine Journal, March 31, 2008. Google has the world’s strongest brandL. Rao, “Guess Which Brand Is Now Worth $100 Billion?” TechCrunch, April 30, 2009. (its name is a verb—just Google it). It is regularly voted among the best firms to work for in America (twice topping Fortune’s list). While rivals continue to innovate (see the box “Search: Google Rules, but It Ain’t Over” in Section 8.10 "The Battle Unfolds") through Q1 2009, Google’s share of the search market has consistently grown while its next two biggest competitors have shrunk.

Figure 8.3 Search Market Share, Year-End 2008Adapted from S. Shankland, “Google Conquers 2008 Search Market in U.S.,” CNET, January 14, 2009.

Figure 8.4 Change in Market Share, 2007–2008Adapted from S. Shankland, “Google Conquers 2008 Search Market in U.S.,” CNET, January 14, 2009.

Wall Street has rewarded this success. The firm’s market capitalization (market cap)The value of a firm calculated by multiplying its share price by the number of shares., the value of the firm calculated by multiplying its share price by the number of shares, makes Google the most valuable media company on the planet. By early 2009, Google’s market cap was greater than that of News Corp (which includes Fox, MySpace, and the Wall Street Journal), Disney (including ABC, ESPN, theme parks, and Pixar), Time Warner (Fortune, Time, Sports Illustrated, CNN, and Warner Bros.), Viacom (MTV, VH1, and Nickelodeon), CBS, and the New York Times—combined! Not bad for a business started by two twenty-something computer science graduate students. By 2007 that duo, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, were billionaires, tying for fifth on the Forbes 400 list of wealthiest Americans.

Genius Geeks and Plum Perks

Brin and Page have built a talent magnet. At the Googleplex, the firm’s Mountain View, California headquarters, geeks are lavished with perks that include on-site laundry, massage, carwash, bicycle repair, free haircuts, state of the art gyms, and wi-fiWireless technologies linking base stations (or hotspots) with devices containing wi-fi chips. Most hotspots have a range of 100 to 300 feet. equipped shuttles that ferry employees between Silicon Valley and the San Francisco Bay area. The Googleplex is also pretty green. The facility gets 30 percent of its energy from solar cells, representing the largest corporate installation of its kind.D. Weldon, “Google’s Power Play,” EnergyDigital, August 30, 2007.

The firm’s quirky tech-centric culture is evident everywhere. A T-Rex skeleton looms near the volleyball court. Hanging from the lobby ceiling is a replica of SpaceShipOne, the first commercial space vehicle. And visitors to the bathroom will find “testing on the toilet,” coding problems or other brainteasers to keep gray matter humming while seated on one of the firm’s $800 remote-controlled Japanese commodes. Staff also enjoy an A-list lecture series attracting luminaries ranging from celebrities to heads of state.

And of course there’s the food—all of it free. The firm’s founders felt that no employee should be more than 100 feet away from nourishment, and a tour around Google offices will find espresso bars, snack nooks, and fully stocked beverage refrigerators galore. There are eleven gourmet cafeterias on site, the most famous being “Charlie’s Place,” first run by the former executive chef for the Grateful Dead.

CEO Eric Schmidt says the goal of all this is “to strip away everything that gets in our employees’ way.”L. Wolgemuth, “Forget the Recession, I Want a Better Chair,” U.S. News and World Report, April 28, 2008. And the perks, culture, and sense of mission have allowed the firm to assemble one of the most impressive rosters of technical talent anywhere. The Googleplex is like a well-fed Manhattan project, and employee ranks have included “Father of the Internet” Vint Cerf; Hal Varian, the former Dean of the U.C. Berkeley School of Information Management and Systems; Kai-Fu Lee, the former head of Microsoft Research in China; and Andy Hertzfeld, one of the developers of the original Macintosh user interface.

Engineers find Google a particularly attractive place to work, in part due to a corporate policy of offering “20 percent time,” the ability work the equivalent of one day a week on new projects that interest them. It’s a policy that has fueled innovation. Google Vice President Marissa Mayer (who herself regularly ranks among Fortune’s most powerful women in business) has stated that roughly half of Google products got their start in 20 percent time.B. Casnocha, “Success on the Side,” The American: The Journal of the American Enterprise Institute, April 24, 2009.

Studying Google gives us an idea of how quickly technology-fueled market disruptions can happen, and how deeply these disruptions penetrate various industries. We’ll also study the underlying technologies that power search, online advertising, and customer profiling. We’ll explore issues of strategy, privacy, fraud, and discuss other opportunities and challenges the firm faces going forward.

Key Takeaways

- Online advertising represents the only advertising category trending with positive growth.

- Google controls the lion’s share of the Internet search advertising business and online advertising dollars. The firm also earns more total advertising revenue than any other firm, online or off.

- Google’s market cap makes it the most valuable media company in the world; it has been rated as having the world’s strongest brand.

Questions and Exercises

- List the reasons why Google has been considered a particularly attractive firm to work for. Are all of these associated with perks?

- Market capitalization and market share change frequently. Investigate Google’s current market cap and compare it with other media companies. Do patterns suggested in this case continue to hold? Why or why not?

- Search industry numbers presented are through year-end 2008, but in mid-year 2009, Microsoft introduced Bing. Research online to find out the most current Google versus Bing versus Yahoo! market share. Does Google’s position seem secure to you? Why or why not?

8.2 Understanding Search

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand the mechanics of search, including how Google indexes the Web and ranks its organic search results.

- Examine the infrastructure that powers Google and how its scale and complexity offer key competitive advantages.

Before diving into how the firm makes money, let’s first understand how Google’s core service, search, works.

Perform a search (or querySearch.) on Google or another search engine, and the results you’ll see are referred to by industry professionals as organic or natural searchSearch engine results returned and ranked according to relevance.. Search engines use different algorithms for determining the order of organic search results, but at Google the method is called PageRankAlgorithm developed by Google cofounder Larry Page to rank Web sites. (a bit of a play on words, it ranks Web pages, and was initially developed by Google cofounder Larry Page). Google does not accept money for placement of links in organic search results. Instead, PageRank results are a kind of popularity contest. Web pages that have more pages linking to them are ranked higher.

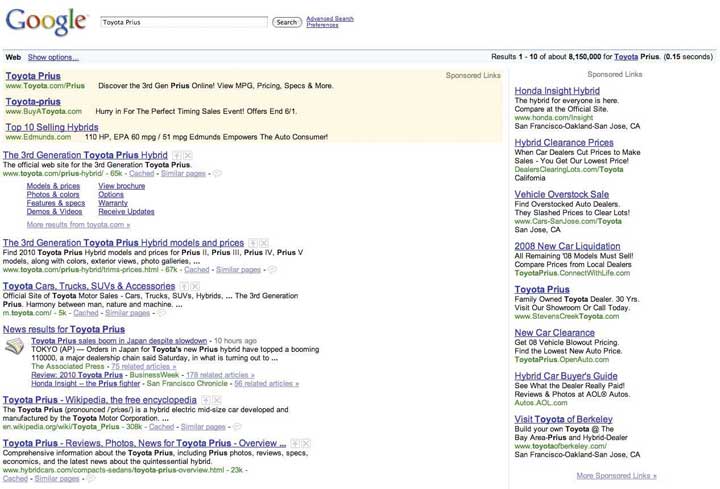

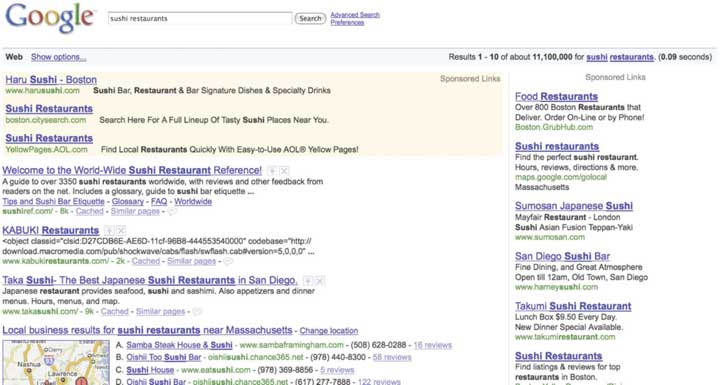

Figure 8.5

The query for “Toyota Prius” triggers organic search results, flanked top and right by sponsored link advertisements.

The process of improving a page’s organic search results is often referred to as search engine optimization (SEO)The process of improving a page’s organic search results.. SEO has become a critical function for many marketing organizations since if a firm’s pages aren’t near the top of search results, customers may never discover its site.

Google is a bit vague about the specifics of precisely how PageRank has been refined, in part because many have tried to game the system. The less scrupulous have tried creating a series of bogus Web sites, all linking back to the pages they’re trying to promote (this is called link fraudAlso called “spamdexing” or “link farming.” The process of creating a series of bogus Web sites, all linking back to the pages one is trying to promote., and Google actively works to uncover and shut down such efforts). We do know that links from some Web sites carry more weight than others. For example, links from Web sites that Google deems as “influential,” and links from most “.edu” Web sites, have greater weight in PageRank calculations than links from run-of-the-mill “.com” sites.

Spiders and Bots and Crawlers—Oh My!

When performing a search via Google or another search engine, you’re not actually searching the Web. What really happens is that the major search engines make what amounts to a copy of the Web, storing and indexing the text of online documents on their own computers. Google’s index considers over one trillion URLs.A. Wright, “Exploring a ‘Deep Web’ That Google Can’t Grasp,” New York Times, February 23, 2009. The upper right-hand corner of a Google query shows you just how fast a search can take place (in the example above, rankings from over eight million results containing the term “Toyota Prius” were delivered in less than two tenths of a second).

To create these massive indexes, search firms use software to crawl the Web and uncover as much information as they can find. This software is referred to by several different names: software robots, spiders, Web crawlersSoftware that traverses available Web links in an attempt to perform a given task. Search engines use spiders to discover documents for indexing and retrieval.. They all pretty much work the same way. In order to make its Web sites visible, every online firm provides a list of all of the public, named servers on its network, known as Domain Name Service (DNS)Internet directory service that allows devices and services to be named and discoverable. The DNS, for example, helps your browser locate the appropriate computers when entering an address like http://finance.google.com. listings. For example, Yahoo! has different servers that can be found at http://www.yahoo.com, sports.yahoo.com, weather.yahoo.com, finance.yahoo.com, et cetera. Spiders start at the first page on every public server and follow every available link, traversing a Web site until all pages are uncovered.

Google will crawl frequently updated sites, like those run by news organizations, as often as several times an hour. Rarely updated, less popular sites might only be reindexed every few days. The method used to crawl the Web also means that if a Web site isn’t the first page on a public server, or isn’t linked to from another public page, then it’ll never be found.Most Web sites do have a link where you can submit a Web site for indexing, and doing so can help promote the discovery of your content. Also note that each search engine also offers a page where you can submit your Web site for indexing.

While search engines show you what they’ve found on their copy of the Web’s contents; clicking a search result will direct you to the actual Web site, not the copy. But sometimes you’ll click a result only to find that the Web site doesn’t match what the search engine found. This happens if a Web site was updated before your search engine had a chance to reindex the changes. In most cases you can still pull up the search engine’s copy of the page. Just click the “Cached” link below the result (the term cacheA temporary storage space used to speed computing tasks. refers to a temporary storage space used to speed computing tasks).

But what if you want the content on your Web site to remain off limits to search engine indexing and caching? Organizations have created a set of standards to stop the spider crawl, and all commercial search engines have agreed to respect these standards. One way is to put a line of HTML code invisibly embedded in a Web site that tells all software robots to stop indexing a page, stop following links on the page, or stop offering old page archives in a cache. Users don’t see this code, but commercial Web crawlers do. For those familiar with HTML code (the language used to describe a Web site), the command to stop Web crawlers from indexing a page, following links, and listing archives of cached pages looks like this:

<META NAME=“ROBOTS” CONTENT=“NOINDEX, NOFOLLOW, NOARCHIVE”>

There are other techniques to keep the spiders out, too. Web site administrators can add a special file (called robots.txt) that provides similar instructions on how indexing software should treat the Web site. And a lot of content lies inside the “dark Web,” either behind corporate firewalls or inaccessible to those without a user account—think of private Facebook updates no one can see unless they’re your friend—all of that is out of Google’s reach.

What’s It Take to Run This Thing?

Sergey Brin and Larry Page started Google with just four scavenged computers.M. Liedtke, “Google Reigns as World’s Most Powerful 10-Year-Old,” Associated Press, September 5, 2008. But in a decade, the infrastructure used to power the search sovereign has ballooned to the point where it is now the largest of its kind in the world.David F. Carr, “How Google Works,” Baseline, July 6, 2006. Google doesn’t disclose the number of servers it uses, but by some estimates, it runs over 1.4 million servers in over a dozen so-called server farmsA massive network of computer servers running software to coordinate their collective use. Server farms provide the infrastructure backbone to SaaS and hardware cloud efforts, as well as many large-scale Internet services. worldwide.R. Katz, “Tech Titans Building Boom,” IEEE Spectrum 46, no. 2 (February 1, 2009). In 2008, the firm spent $2.18 billion on capital expenditures, with data centers, servers, and networking equipment eating up the bulk of this cost.Google, “Google Announces Fourth Quarter and Fiscal Year 2008 Results,” press release, January 22, 2009. Building massive server farms to index the ever-growing Web is now the cost of admission for any firm wanting to compete in the search market. This is clearly no longer a game for two graduate students working out of a garage.

Video Clip

Google’s Container Data Center

Take a virtual tour of one of Google’s data centers.

The size of this investment not only creates a barrier to entry, it influences industry profitability, with market-leader Google enjoying huge economies of scale. Firms may spend the same amount to build server farms, but if Google has two-thirds of this market (and growing) while Microsoft’s search draws only about one-tenth the traffic, which do you think enjoys the better return on investment?

The hardware components that power Google aren’t particularly special. In most cases the firm uses the kind of Intel or AMD processors, low-end hard drives, and RAM chips that you’d find in a desktop PC. These components are housed in rack-mounted servers about 3.5 inches thick, with each server containing two processors, eight memory slots, and two hard drives.

In some cases, Google mounts racks of these servers inside standard-sized shipping containers, each with as many as 1,160 servers per box.S. Shankland, “Google Unlocks Once-Secret Server,” CNET, April 1, 2009. A given data center may have dozens of these server-filled containers all linked together. Redundancy is the name of the game. Google assumes individual components will regularly fail, but no single failure should interrupt the firm’s operations (making the setup what geeks call fault-tolerantSystems that are capable of continuing operation even if a component fails.). If something breaks, a technician can easily swap it out with a replacement.

Each server farm layout has also been carefully designed with an emphasis on lowering power consumption and cooling requirements. And the firm’s custom software (much of it built upon open-source products) allows all this equipment to operate as the world’s largest grid computer.

Web search is a task particularly well suited for the massively parallel architecture used by Google and its rivals. For an analogy of how this works, imagine that working alone, you need try to find a particular phrase in a hundred-page document (that’s a one server effort). Next, imagine that you can distribute the task across five thousand people, giving each of them a separate sentence to scan (that’s the multi-server grid). This difference gives you a sense of how search firms use massive numbers of servers and the divide-and-conquer approach of grid computing to quickly find the needles you’re searching for within the Web’s haystack (for more on grid computing, see Chapter 4 "Moore’s Law and More: Fast, Cheap Computing and What It Means for the Manager", and for more on server farms, see Chapter 10 "Software in Flux: Partly Cloudy and Sometimes Free").

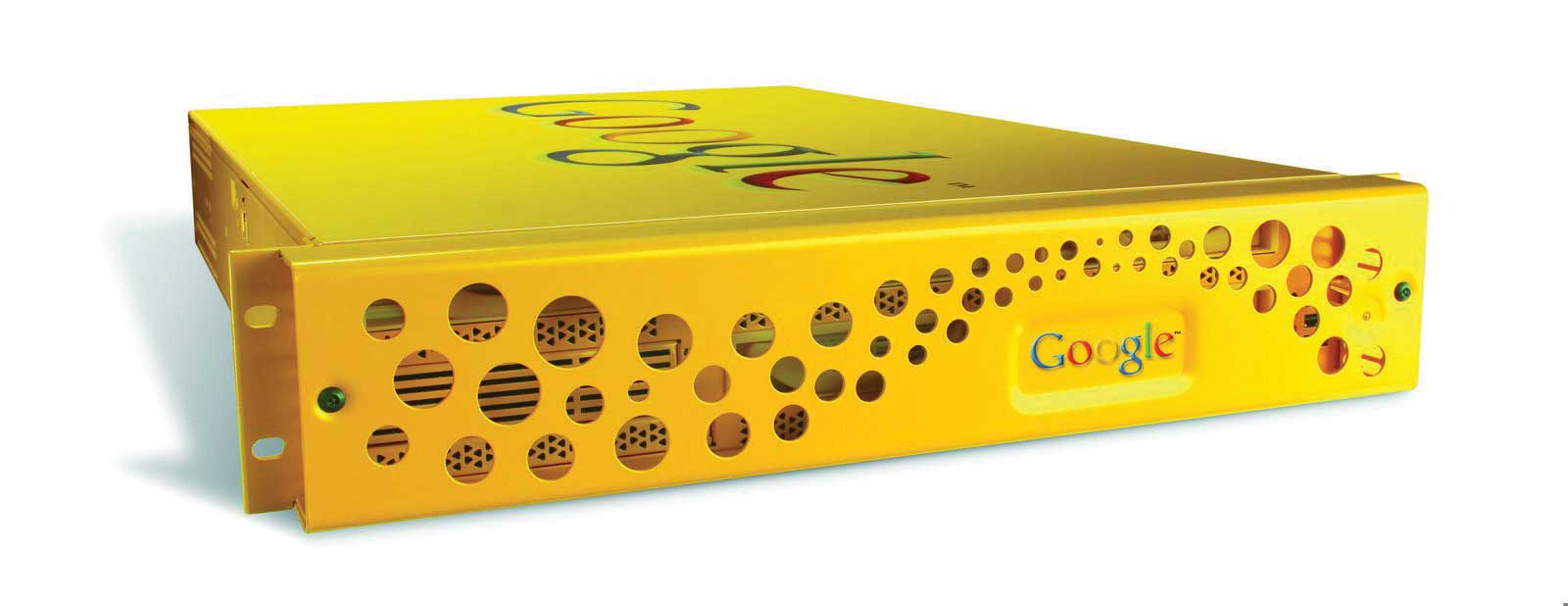

Figure 8.6

The Google Search Appliance is a hardware product that firms can purchase in order to run Google search technology within the privacy and security of an organization’s firewall.

Google will even sell you a bit of its technology so that you can run your own little Google in-house without sharing documents with the rest of the world. Google’s line of search appliances are rack-mounted servers that can index documents within a corporation’s Web site, even specifying password and security access on a per-document basis. Selling hardware isn’t a large business for Google, and other vendors offer similar solutions, but search appliances can be vital tools for law firms, investment banks, and other document-rich organizations.

Trendspotting with Google

Google not only gives you search results, it lets you see aggregate trends in what its users are searching for, and this can yield powerful insights. For example, by tracking search trends for flu symptoms, Google’s Flu Trends Web site can pinpoint outbreaks one to two weeks faster than the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.S. Bruce, “Google Says User Data Aids Flu Detection,” eHealthInsider, May 25, 2009. Want to go beyond the flu? Google’s Trends, and Insights for Search services allow anyone to explore search trends, breaking out the analysis by region, category (image, news, product), date, and other criteria. Savvy managers can leverage these and similar tools for competitive analysis, comparing a firm, its brands, and its rivals.

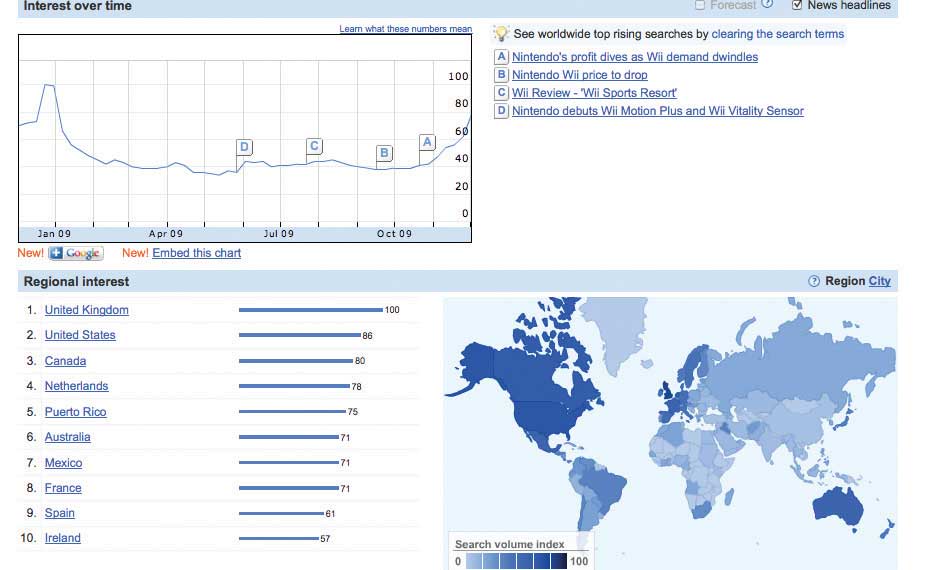

Figure 8.7

Google Insights for Search can be a useful tool for competitive analysis and trend discovery. The chart shows a comparison (over a twelve-month period, and geographically) of search interest in the terms Wii, Playstation, and Xbox.

Key Takeaways

- Ranked search results are often referred to as organic or natural search. PageRank is Google’s algorithm for ranking search results. PageRank orders organic search results based largely on the number of Web sites linking to them, and the “weight” of each page as measured by its “influence.”

- Search engine optimization (SEO) is the process of using natural or organic search to increase a Web site’s traffic volume and visitor quality. The scope and influence of search has made SEO an increasingly vital marketing function.

- Users don’t really search the Web; they search an archived copy built by crawling and indexing discoverable documents.

- Google operates from a massive network of server farms containing hundreds of thousands of servers built from standard, off-the-shelf items. The cost of the operation is a significant barrier to entry for competitors. Google’s share of search suggests the firm can realize economies of scales over rivals required to make similar investments while delivering fewer results (and hence ads).

- Web site owners can hide pages from popular search-engine Web crawlers using a number of methods, including HTML tags, a no-index file, or ensuring that Web sites aren’t linked to other pages and haven’t been submitted to Web sites for indexing.

Questions and Exercises

- How do search engines discover pages on the Internet? What kind of capital commitment is necessary to go about doing this? How does this impact competitive dynamics in the industry?

- How does Google rank search results? Investigate and list some methods that an organization might use to improve its rank in Google’s organic search results. Are there techniques Google might not improve of? What risk does a firm run if Google or another search firm determines that it has used unscrupulous SEO techniques to try to game ranking algorithms?

- Sometimes Web sites returned by major search engines don’t contain the words or phrases that initially brought you to the site. Why might this happen?

- What’s a cache? What other products or services have a cache?

- What can be done if you want the content on your Web site to remain off limits to search engine indexing and caching?

- What is a “search appliance?” Why might an organization choose such a product?

- Become a better searcher: Look at the advanced options for your favorite search engine. Are there options you hadn’t used previously? Be prepared to share what you learn during class discussion.

- Visit Google Trends and Google Insights for Search. Explore the tool as if you were comparing a firm with its competitors. What sorts of useful insights can you uncover? How might businesses use these tools?

8.3 Understanding the Increase in Online Ad Spending

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand how media consumption habits are shifting.

- Be able to explain the factors behind the growth and appeal of online advertising.

For several years, Internet advertising has been the only major media ad category to show significant growth. There are three factors driving online ad growth trends: (1) increased user time online, (2) improved measurement and accountability, and (3) targeting.

American teenagers (as well as the average British, Australian, and New Zealander Web surfer) now spend more time on the Internet than watching television.“American Teenagers Spend More Time Online Than Watching Television,” MediaWeek, June 19, 2008; A. Hendry, “Connected Aussies Spend More Time Online Than Watching TV,” Computerworld Australia, May 21, 2008; and “Brits Spend More Time Online Than Watching TV,” BigMouthMedia, July 12, 2007. They’re reading fewer print publications, and radio listening among the iPod generation is down 30 percent.M. Tobias, “Newspapers under Siege,” Philstar, May 18, 2009. So advertisers are simply following the market. Online channels also provide advertisers with a way to reach consumers at work—something that was previously much more difficult to do.

Many advertisers have also been frustrated by how difficult it’s been to gauge the effectiveness of traditional ad channels such as TV, print, and radio. This frustration is reflected in the old industry saying, “I know that half of my advertising is working—I just don’t know which half.” Well, with the Internet, now you know. While measurement technologies aren’t perfect, advertisers can now count ad impressionsEach time an ad is served to a user for viewing. (each time an ad appears on a Web site), whether or not a user clicks on an ad, and the product purchases or other Web site activity that comes from those clicks.For a more detailed overview of the limitations in online ad measurement, see L. Rao, “Guess Which Brand Is Now Worth $100 Billion?” TechCrunch, April 30, 2009. And as we’ll see, many online ad payment schemes are directly linked to ad performance.

Various technologies and techniques also make it easier for firms to target users based on how likely a person is to respond to an ad. In theory a firm can use targeting to spend marketing dollars only on those users deemed to be its best prospects. Let’s look at a few of these approaches in action.

Key Takeaways

- There are three reasons driving online ad growth trends: (1) increasing user time online, (2) improved measurement and accountability, and (3) targeting.

- Digital media is decreasing time spent through traditional media consumption channels (e.g., radio, TV, newspapers), potentially lowering the audience reach of these old channels and making them less attractive for advertisers.

- Measurement techniques allow advertisers to track the performance of their ads—indicating things such as how often an ad is displayed, how often an is clicked, where an ad was displayed when it was clicked, and more. Measurement metrics can be linked to payment schemes, improving return on investment (ROI) and accountability compared to many types of conventional advertising.

- Advertising ROI can be improved through targeting. Targeting allows a firm to serve ads to specific categories of users, so firms can send ads to groups it is most interested in reaching, and those that are most likely to respond to an effort.

Questions and Exercises

- How does your media time differ from your parents? Does it differ among your older or younger siblings, or other relatives? Which media are you spending more time with? Less time with?

- Put yourself in the role of a traditional media firm that is seeing its market decline. What might you do to address decline concerns? Have these techniques been attempted by other firms? Do you think they’ve worked well? Why or why not?

- Put yourself in the role of an advertiser for a product or service that you’re interested in. Is the Internet an attractive channel for you? How might you use the Internet to reach customers you are most interested in? Where might you run ads? Who might you target? Who might you avoid? How might the approach you use differ from traditional campaigns you’d run in print, TV, or radio? How might the size (money spent, attempted audience reach) and timing (length of time run, time between campaigns) of ad campaigns online differ from offline campaigns?

- List ways in which you or someone you know has been targeted in an Internet ad campaign. Was it successful? How do you feel about targeting?

8.4 Search Advertising

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand Google’s search advertising revenue model.

- Know the factors that determine the display and ranking of advertisements appearing on Google’s search results pages.

- Be able to describe the uses and technologies behind geotargeting.

The practice of running and optimizing search engine ad campaigns is referred to as search engine marketing (SEM)The practice of designing, running and optimizing search-engine ad campaigns..S. Elliott, “More Agencies Investing in Marketing with a Click,” New York Times, March 14, 2006. SEM is a hot topic in an increasingly influential field, so it’s worth spending some time learning how search advertising works on the Internet’s largest search engine.

Roughly two-thirds of Google’s revenues come from ads served on its own sites, and the vast majority of this revenue comes from search engine ads.Google, “Google Announces Fourth Quarter and Fiscal Year 2008 Results,” press release, January 22, 2009. During Google’s early years, the firm actually resisted making money through ads. In fact, while at Stanford, Brin and Page even coauthored a paper titled “The Evils of Advertising.”D. Vise, “Google’s Decade,” Technology Review, September 12, 2008. But when Yahoo! and others balked at buying Google’s search technology (offered for as little as $500,000), Google needed to explore additional revenue streams. It wasn’t until two years after incorporation that Google ran ads alongside organic search results. That first ad, one for “Live Mail Order Lobsters,” appeared just minutes after the firm posted a link reading “See Your Ad Here”).S. Levy, “The Secrets of Googlenomics,” Wired, June 2009.

Google has only recently begun incorporating video and image ads into search. For the most part, the ads you’ll see to the right (and sometimes top) of Google’s organic search results appear as keyword advertisingAdvertisements that are targeted based on a user’s query., meaning they’re targeted based on a user’s query. Advertisers bid on the keywords and phrases that they’d like to use to trigger the display of their ad. Linking ads to search was a brilliant move, since the user’s search term indicates an overt interest in a given topic. Want to sell hotel stays in Tahiti? Link your ads to the search term “Tahiti Vacation.”

Not only are search ads highly targeted, advertisers only pay for results. Text ads appearing on Google search pages are billed on a pay-per-click (PPC)A concept where advertisers don’t pay unless someone clicks on their ad. basis, meaning that advertisers don’t spend a penny unless someone actually clicks on their ad. Note that the term pay-per-click is sometimes used interchangeably with the term cost-per-click (CPC)The maximum amount of money an advertiser is willing to pay for each click on their ad..

Not Entirely Google’s Idea

Google didn’t invent pay-for-performance search advertising. A firm named GoTo.com (later renamed Overture) pioneered pay-per-click ads and bidding systems and held several key patents governing the technology. Overture provided pay-per-click ad services to both Yahoo! and Microsoft, but it failed to refine and match the killer combination of ad auctions and search technology that made Google a star. Yahoo! eventually bought Overture and sued Google for patent infringement. In 2004, the two firms settled, with Google giving Yahoo! 2.7 million shares in exchange for a “fully paid, perpetual license” to over sixty Overture patents.S. Olsen, “Google, Yahoo Bury the Legal Hatchet,” CNET, August 9, 2004.

If an advertiser wants to display an ad on Google search, they can set up a Google AdWords advertising account in minutes, specifying just a single ad, or multiple ad campaigns that trigger different ads for different keywords. Advertisers also specify what they’re willing to pay each time an ad is clicked, how much their overall ad budget is, and they can control additional parameters, such as the timing and duration of an ad campaign.

If no one clicks on an ad, Google doesn’t make money, advertisers don’t attract customers, and searchers aren’t seeing ads they’re interested in. So in order to create a winning scenario for everyone, Google has developed a precise ad ranking formula that rewards top performing ads by considering two metrics: the maximum CPC that an advertiser is willing to pay, and the advertisement’s quality scoreA broad measure of ad performance.—a broad measure of ad performance. Create high quality ads and your advertisements might appear ahead of competition, even if your competitors bid more than you. But if ads perform poorly they’ll fall in rankings or even drop from display consideration.

Below is the formula used by Google to determine the rank order of sponsored links appearing on search results pages.

Ad Rank = Maximum CPC × Quality ScoreOne factor that goes into determining an ad’s quality score is the click-through rate (CTR)The number of users who clicked an ad divided by the number of times the ad was delivered (the impressions). The CTR measures the percentage of people who clicked on an ad to arrive at a destination site. for the ad, the number of users who clicked an ad divided by the number of times the ad was delivered (the impressions). The CTR measures the percentage of people who clicked on an ad to arrive at a destination site. Also included in a quality score are the overall history of click performance for the keywords linked to the ad, the relevance of an ad’s text to the user’s query, and Google’s automated assessment of the user experience on the landing pageThe Web site displayed when a user clicks on an advertisement.—the Web site displayed when a user clicks on the ad. Ads that don’t get many clicks, ad descriptions that have nothing to do with query terms, and ads that direct users to generic pages that load slowly or aren’t strongly related to the keywords and descriptions used in an ad, will all lower an ad’s chance of being displayed.Google, Marketing and Advertising Using Google: Targeting Your Advertising to the Right Audience (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2007).

When an ad is clicked, advertisers don’t actually pay their maximum CPC; Google discounts ads to just one cent more than the minimum necessary to maintain an ad’s position on the page. So if you bid one dollar per click, but the ad ranked below you bids ninety cents, you’ll pay just ninety-one cents if the ad is clicked. Discounting was a brilliant move. No one wants to get caught excessively overbidding rivals, so discounting helps reduce the possibility of this so-called bidder’s remorse. And with this risk minimized, the system actually encouraged higher bids!S. Levy, “The Secrets of Googlenomics,” Wired, June 2009.

Ad ranking and cost-per-click calculations take place as part of an automated auction that occurs every time a user conducts a search. Advertisers get a running total of ad performance statistics so that they can monitor the return on their investment and tweak promotional efforts for better results. And this whole system is automated for self-service—all it takes is a credit card, an ad idea, and you’re ready to go.

How Much Do Advertisers Pay per Click?

Google rakes in billions on what amounts to pocket change earned one click at a time. Most clicks bring in between thirty cents and one dollar. However, costs can vary widely depending on industry, current competition, and perceived customer value. Table 8.1 "10 Most Expensive Industries for Keyword Ads" shows some of the highest reported CPC rates. But remember, any values fluctuate in real time based on auction participants.

Table 8.1 10 Most Expensive Industries for Keyword Ads

| Business/Industry | Keywords in the Top 25 | Avg. CPC |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Settlements | 2 | $51.97 |

| Secured Loans | 2 | $50.67 |

| Buying Endowments | 1 | $50.35 |

| Mesothelioma Lawyers | 5 | $50.30 |

| DUI Lawyers | 4 | $49.78 |

| Conference Call Companies | 1 | $49.64 |

| Car Insurance Quotes | 3 | $49.61 |

| Student Loan Consolidation | 3 | $49.44 |

| Data Recovery | 2 | $49.43 |

| Remortgages | 2 | $49.42 |

Source: X. Becket, “10 Businesses with the Highest Cost Per Click,” WebPageFX Weekly, February 20, 2009.

Since rates are based on auctions, top rates reflect what the market is willing to bear. As an example, law firms, which bring in big bucks from legal fees, decisions, and settlement payments often justify higher customer acquisition costs. And firms that see results will keep spending. Los Angeles–based Chase Law Group has said that it brings in roughly 60 percent of its clients through Internet advertising.C. Mann, “How Click Fraud Could Swallow the Internet,” Wired, January 2006.

IP Addresses and Geotargeting

GeotargetingIdentifying a user’s physical location (sometimes called geolocation) for the purpose of delivering tailored ads or other content. occurs when computer systems identify a user’s physical location (sometimes called the geolocation) for the purpose of delivering tailored ads or other content. On Google AdWords, for example, advertisers can specify that their ads only appear for Web surfers located in a particular country, state, metropolitan region, or a given distance around a precise locale. They can even draw a custom ad-targeting region on a map and tell Google to only show ads to users detected inside that space.

Ads in Google Search are geotargeted based on IP addressA value used to identify a device that is connected to the Internet. IP addresses are usually expressed as four numbers (from 0 to 255), separated by periods.. Every device connected to the Internet has a unique IP address assigned by the organization connecting the device to the network. Normally you don’t see your IP address (a set of four numbers, from 0 to 255, separated by periods; e.g., 136.167.2.220). But the range of IP addresses “owned” by major organizations and Internet service providers (ISPs) is public knowledge. In many cases it’s possible to make an accurate guess as to where a computer, laptop, or mobile phone is located simply by cross-referencing a device’s current IP address with this public list.

For example, it’s known that all devices connected to the Boston College network contain IP addresses starting with the numbers 136.167. If a search engine detects a query coming from an IP address that begins with those two numbers, it can be fairly certain that the person using that device is in the greater Boston area.

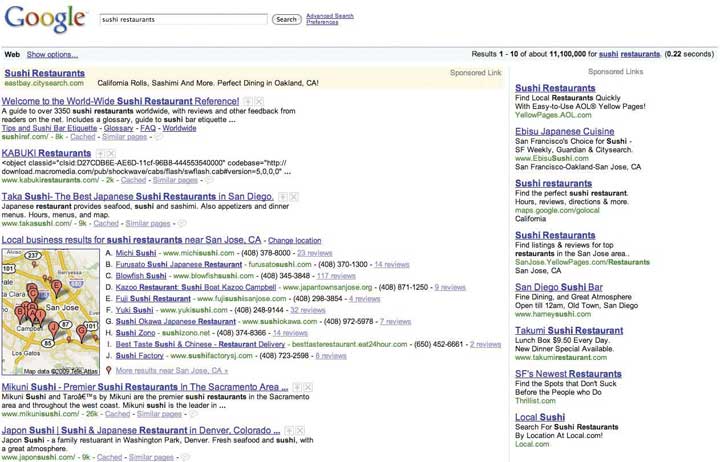

Figure 8.8

Figure 8.9

In this geotargeting example, the same search term is used at roughly the same time on separate computers located in Silicon Valley area (top) and Boston (bottom). Note how geotargeting impacts results.

IP addresses will change depending on how and where you connect to the Internet. Connect your laptop to a hotel’s wi-fi when visiting a new city, and you’re likely to see ads specific to that location. That’s because your Internet service provider has changed, and the firm serving your ads has detected that you are using an IP address known to be associated with your new location.

Geotargeting via IP address is fairly accurate, but it’s not perfect. For example, some Internet service providers may provide imprecise or inaccurate information on the location of their networks. Others might be so vague that it’s difficult to make a best guess at the geography behind a set of numbers (values assigned by a multinational corporation with many locations, for example). And there are other ways locations are hidden, such as when Internet users connect to proxy serversA third-party computer that passes traffic to and from a specific address without revealing the address of the connected user., third-party computers that pass traffic to and from a specific address without revealing the address of the connected users.

What’s My IP Address?

While every operating system has a control panel or command that you can use to find your current IP address, there are also several Web sites that will quickly return this value (and a best guess at your current location). One such site is http://ip-adress.com (note the spelling has only one “d”). Visit this or a similar site with a desktop, laptop, and mobile phone. Do the results differ and are they accurate? Why?

Geotargeting Evolves Beyond the IP Address

There are several other methods of geotargeting. Firms like Skyhook Wireless can identify a location based on its own map of wi-fi hotspots and nearby cell towers. Many mobile devices come equipped with global positioning system (GPS)A network of satellites and supporting technologies used to identify a device’s physical location. chips (identifying location via the GPS satellite network). And if a user provides location values such as a home address or zip code to a Web site, then that value might be stored and used again to make a future guess at a user’s location.

Key Takeaways

- Roughly two-thirds of Google’s revenues come from ads served on its own sites, and the vast majority of this revenue comes from search engine ads.

- Advertisers choose and bid on the keywords and phrases that they’d like to use to trigger the display of their ad.

- Advertisers pay for cost-per-click advertising only if an ad is clicked on. Google makes no money on CPC ads that are displayed but not clicked.

- Google determines ad rank by multiplying CPC by Quality Score. Ads with low ranks might not display at all.

- Advertisers usually don’t pay their maximum CPC. Instead, Google discounts ads to just one cent more than the minimum necessary to maintain an ad’s position on the page—a practice that encourages higher bids.

- Geotargeting occurs when computer systems identify a user’s physical location (sometimes called geolocation) for the purpose of delivering tailored ads or other content.

- Google uses IP addresses to target ads.

Questions and Exercises

- Which firm invented pay-per-click advertising? Why does Google dominate today and not this firm?

- How are ads sold via Google search superior to conventional advertising media such as TV, radio, billboard, print, and yellow pages? Consider factors like the available inventory of space to run ads, the cost to run ads, the cost to acquire new advertisers, and the appeal among advertisers.

- Are there certain kinds of advertising campaigns and goals where search advertising wouldn’t be a good fit? Give examples and explain why.

- Can a firm buy a top ad ranking? Why or why not?

- List the four factors that determine an ad’s quality score.

- How much do firms typically pay for a single click?

- Sites like SpyFu.com and KeywordSpy.com provide a list of the keywords with the highest cost per click. Visit the Top Lists page at SpyFu, KeywordSpy, or a comparable site, to find estimates of the current highest paying cost per click. Which key words pay the most? Why do you think firms are willing to spend so much?

- What is bidder’s remorse? How does Google’s ad discounting impact this phenomenon?

- Visit http://www.ip-adress.com/using a desktop, laptop, and mobile phone (work with a classmate or friend if you don’t have access to one of these devices). How do results differ? Why? Are they accurate? What factors go into determining the accuracy of IP-based geolocation?

- List and briefly describe other methods of geotargeting besides IP address, and indicate the situations and devices where these methods would be more and less effective.

- The field of search engine marketing (SEM) is relatively new and rising in importance. And since the field is so new and constantly changing, there are plenty of opportunities for young, knowledgeable professionals. Which organizations, professional certification, and other resources are available to SEM professionals? Spend some time searching for these resources online and be prepared to share your findings with your class.

8.5 Ad Networks—Distribution beyond Search

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand ad networks, and how ads are distributed and served based on Web site content.

- Recognize how ad networks provide advertiser reach and support niche content providers.

- Be aware of content adjacency problems and their implications.

- Know the strategic factors behind ad network appeal and success.

Google runs ads not just in search, but also across a host of Google-owned sites like Gmail, Google News, and Blogger. It will even tailor ads for its map products and for mobile devices. But about 30 percent of Google’s revenues come from running ads on Web sites that the firm doesn’t even own.Google, “Google Announces Fourth Quarter and Fiscal Year 2008 Results,” press release, January 22, 2009.

Next time you’re surfing online, look around the different Web sites that you visit and see how many sport boxes labeled “Ads by Google.” Those Web sites are participating in Google’s AdSense ad network, which means they’re running ads for Google in exchange for a cut of the take. Participants range from small-time bloggers to some of the world’s most highly trafficked sites. Google lines up the advertisers, provides the targeting technology, serves the ads, and handles advertiser payment collection. To participate, content providers just sign up online, put a bit of Google-supplied HTML code on their pages, and wait for Google to send them cash (Web sites typically get about seventy to eighty cents for every AdSense dollar that Google collects).B. Tedeschi, “Google’s Shadow Payroll Is Not Such a Secret Anymore,” New York Times, January 16, 2006.

Google originally developed AdSense to target ads based on keywords automatically detected inside the content of a Web site. A blog post on your favorite sports team, for example, might be accompanied by ads from ticket sellers or sports memorabilia vendors. AdSense and similar online ad networks provide advertisers with access to the long tail of niche Web sites by offering both increased opportunities for ad exposure as well as more-refined targeting opportunities.

Figure 8.10

The images show advertising embedded around a story on the New York Times Web site. The page runs several ads provided by different ad networks. For example, the WebEx banner ad above the article’s headline was served by AOL-owned Platform-A/Tacoda. The “Ads by Google” box appeared at the end of the article. Note how the Google ads are related to the content of the Times article.

Running ads on your Web site is by no means a guaranteed path to profits. The Internet graveyard is full of firms that thought they’d be able to sustain their businesses on ads alone. But for many Web sites, ad networks can be like oxygen, sustaining them with revenue opportunities they’d never be able to achieve on their own.

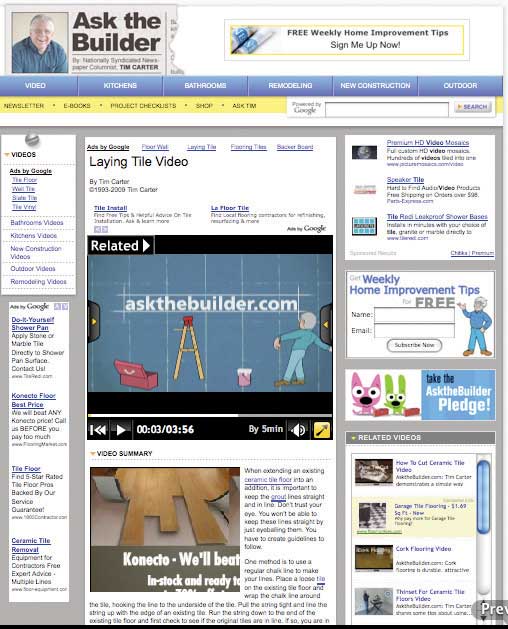

For example, AdSense provided early revenue for the popular social news site Digg, as well as the multimillion-dollar TechCrunch media empire. It supports Disaboom, a site run by physician and quadriplegic Dr. Glen House. And it continues to be the primary revenue generator for AskTheBuilder.com. That site’s founder, former builder Tim Carter, had been writing a handyman’s column syndicated to some thirty newspapers. The newspaper columns didn’t bring in enough to pay the bills, but with AdSense he hit pay dirt, pulling in over $350,000 in ad revenue in just his first year!R. Rothenberg, “The Internet Runs on Ad Billions,” BusinessWeek, April 10, 2008.

Figure 8.11

Tim Carter’s Ask the Builder Web site runs ads from Google and other ad networks. Note different ad formats surrounding the content. There’s even an ad in the bottom of the video, served from Google-owned YouTube.

Beware the Content Adjacency Problem

Contextual advertisingAdvertising based on a Web sites content. based on keywords is lucrative, but like all technology solutions it has its limitations. Vendors sometimes suffer from content adjacency problemsA situation where ads appear alongside text the advertiser would like to avoid. when ads appear alongside text they’d prefer to avoid. In one particularly embarrassing example, a New York Post article detailed a gruesome murder where hacked up body parts were stowed in suitcases. The online version of the article included contextual advertising and was accompanied by…luggage ads.A. Overholt, “Search for Tomorrow,” Fast Company, December 19, 2007.

To combat embarrassment, ad networks provide opportunities for both advertisers and content providers to screen out potentially undesirable pairings based on factors like vendor, Web site, keyword, and category. Ad networks also refine ad-placement software based on feedback from prior incidents (for more on content adjacency problems, see Chapter 7 "Facebook: Building a Business from the Social Graph").

Google launched AdSense in 2003, but Google is by no means the only company to run an ad network, nor was it the first to come up with the idea. Rivals include the Yahoo! Publisher Network, Microsoft’s adCenter, and AOL’s Platform-A. Others, like Quigo, don’t even have a consumer Web site yet manage to consolidate enough advertisers to attract high-traffic content providers such as ESPN, Forbes, Fox, and USA Today. Advertisers also aren’t limited to choosing just one ad network. In fact, many content provider Web sites will serve ads from several ad networks (as well as exclusive space sold by their own sales force), oftentimes mixing several different offerings on the same page.

Ad Networks and Competitive Advantage

While advertisers can use multiple ad networks, there are several key strategic factors driving the industry. For Google, its ad network is a distribution play. The ability to reach more potential customers across more Web sites attracts more advertisers to Google. And content providers (the Web sites that distribute these ads) want there to be as many advertisers as possible in the ad networks that they join, since this should increase the price of advertising, the number of ads served, and the accuracy of user targeting. If advertisers attract content providers, which in turn attract more advertisers, then we’ve just described network effects! More participants bringing in more revenue also help the firm benefit from scale economies—offering a better return-on-investment from its ad technology and infrastructure. No wonder Google’s been on such a tear—the firm’s loaded with assets for competitive advantage!

Google’s Ad Reach Gets Bigger

While Google has the largest network specializing in distributing text ads, it had been a laggard in graphical display ads (sometimes called image ads). That changed in 2008, with the firm’s $3.1 billion acquisition of display ad network and targeting company DoubleClick. Now in terms of the number of users reached, Google controls both the largest text ad network and the largest display ad network.L. Baker, “Google Now Controls 69% of Online Advertising Market,” Search Engine Journal, March 31, 2008.

Key Takeaways

- Google also serves ads through non-Google partner sites that join its ad network. These partners distribute ads for Google in exchange for a percentage of the take.

- AdSense ads are targeted based on keywords that Google detects inside the content of a Web site.

- AdSense and similar online ad networks provide advertisers with access to the long tail of niche Web sites.

- Ad networks handle advertiser recruitment, ad serving, and revenue collection, opening up revenue earning possibilities to even the smallest publishers.

Questions and Exercises

- On a percentage basis, how important is AdSense to Google’s revenues?

- Why do ad networks appeal to advertisers? What do they appeal to content providers? What functions are assumed by the firm overseeing the ad network?

- What factors determine the appeal of an ad network to advertisers and content providers? Which of these factors are potentially sources of competitive advantage?

- Do dominant ad networks enjoy strong network effects? Are there also strong network effects that drive consumers to search? Why or why not?

- How difficult is it for a Web site to join an ad network? What does this imply about ad network switching costs? Does it have to exclusively choose one network over another? Does ad network membership prevent a firm from selling its own online advertising, too?

- What is the content adjacency problem? Why does it occur? What classifications of Web sites might be particularly susceptible to the content adjacency problem? What can ad networks do to minimize the content adjacency problem for their advertisers? Are there tradeoffs to these approaches?

8.6 More Ad Formats and Payment Schemes

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Know the different formats and media types that Web ads can be displayed in.

- Know the different ways ads are sold.

- Know that games can be an ad channel under the correct conditions.

Online ads aren’t just about text ads billed in CPC. Ads running through Google AdSense, through its DoubleClick subsidiary, or on most competitor networks can be displayed in several formats and media types, and can be billed in different ways. The specific ad formats supported depend on the ad network but can include the following: image (or display) adsGraphical advertising (as opposed to text ads). (such as horizontally oriented banners, smaller rectangular buttons, and vertically oriented “skyscraper” ads); rich media adsOnline ads that include animation, audio, or video. (which can include animation or video); and interstitialsAds that run before a user arrives at a Web site’s contents. (ads that run before a user arrives at a Web site’s contents). The industry trade group, the Internet Advertising Bureau (IAB)A nonprofit industry trade group for the interactive advertising industry. The IAB evaluates and recommends interactive advertising standards and practices and also conducts research, education, and legislative lobbying. sets common standards for display ads so that a single creativeThe design and content of the advertisement. (the design and content of the advertisement) can run unmodified across multiple ad networks and Web sites.See Interactive Advertising Bureau Ad Unit Guidelines for details at http://www.iab.net/iab_products_and_industry_services/1421/1443/1452.

And there are lots of other ways ads are sold besides cost-per-click. Most graphical display ads are sold according to the number of times the ad appears (the impression). Ad rates are quoted in CPMCost per thousand impressions (the M representing the roman numeral for one thousand)., meaning cost per thousand impressions (the M representing the roman numerical for one thousand). Display ads sold on a CPM basis are often used as part of branding campaigns targeted more at creating awareness than generating click-throughs. Such techniques often work best for promoting products like soft drinks, toothpaste, or movies.

Cost-per-action (CPA)A method of charging for adverting whenever a user performs a specified action such as signing up for a service, requesting material, or making a purchase. ads pay whenever a user performs a specified action such as signing up for a service, requesting material, or making a purchase. Affiliate programsA cost-per-action program, where program sponsors (e.g., Amazon.com, iTunes) pay referring Web sites a percentage of revenue earned from the referral. are a form of cost-per-action, where Web sites share a percentage of revenue earned when a user click-throughs and buys something from their Web site. Amazon runs the world’s largest affiliate program, and referring sites earn can earn 4 percent to 15 percent of sales generated from these click-throughs. Purists might not consider affiliate programs as advertising (rather than text or banner ads, Amazon’s affiliates offer links and product descriptions that point back to Amazon’s Web site), but these programs can be important tools in a firm’s promotional arsenal.

Figure 8.12

Some firms sell sponsorship opportunities. The movie 500 Days of Summer sponsored the printer-friendly formatting of New York Times articles.

Figure 8.13

Abbott Laboratories sponsored a special section from HealthCentral.com on the Crohn’s Health Center site.

And rather than buying targeted ads, a firm might sometimes opt to become an exclusive advertiser on a site. For example, a firm could buy access to all ads served on a site’s main page; it could secure exclusive access to a region of the page (such as the topmost banner ad); or it may pay to sponsor a particular portion or activity on a Web site (say a parenting forum, or a “click-to-print” button). Such deals can be billed based on a flat rate, CPM, CPC, or any combination of metrics.

Ads in Games?

As consumers spend more time in video games, it’s only natural that these products become ad channels, too. Finding a sensitive mix that introduces ads without eroding the game experience can be a challenge. Advertising can work in racing or other sports games (in 2008 the Obama campaign famously ran virtual billboards in EA’s Burnout Paradise), but ads make less sense for games set in the past, future, or on other worlds. Branding ads often work best, since click-throughs are typically not something you want disrupting your gaming experience.

Advertisers have also explored sponsorships of Web-based and mobile games. Sponsorships often work best with casual games, such as those offered on Yahoo! Games or EA’s Pogo. Firms have also created online mini games (so-called advergamesWeb-based and mobile games that advertisers develop and offer as a way of building immersive brand engagements.) for longer term, immersive brand engagement (e.g., Mini Cooper’s Slide Parking and Stride Gum’s Chew Challenge). Others have tried a sort of virtual product placement integrated into experiences. A version of The Sims, for example, included virtual replicas of real-world inventory from IKEA and H&M.

Figure 8.14 Obama Campaign’s Virtual Billboard in EA’s Burnout Paradise

Source: Barack Obama U.S. Presidential Campaign Team, 2008.

In-game ad-serving technology also lacks the widely accepted standards of Web-based ads, so it’s unlikely that ads designed for a Wii sports game could translate into a PS3 first-person shooter. Also, one of the largest in-game ad networks, Massive, is owned by Microsoft. That’s good if you want to run ads on XBox, but Microsoft isn’t exactly a firm that Nintendo or Sony want to play nice with.

In-game advertising shows promise, but the medium is considerably more complicated than conventional Web site ads. That complexity lowers relative ROI and will likely continue to constrain growth.

Key Takeaways

- Web ad formats include, but are not limited to, the following: image (or display) ads (such as horizontally oriented banners, smaller rectangular buttons, and vertically oriented skyscraper ads), rich media ads (which can include animation or video), and interstitials (ads that run before a user arrives at a Web site’s contents).

- In addition to cost-per-click, ads can be sold based on the number of times the ad appears (impressions), whenever a user performs a specified action such as signing up for a service, requesting material, or making a purchase (cost-per-action), or on an exclusive basis which may be billed at a flat rate.

- In-game advertising shows promise, with successful branding campaigns run as part of sports games, through in-game product placement, or via sponsorship of casual games, or in brand-focused advergames.

- A lack of standards, concerns regarding compatibility with gameplay, and the cost of developing and distributing games are all stifling the growth of in-game ads.

Questions and Exercises

- What is the IAB and why is it necessary?

- What are the major ad format categories?

- What’s an interstitial? What’s a rich media ad? Have you seen these? Do you think they are effective? Why or why not?

- List four major methods for billing online advertising.

- Which method is used to bill most graphical advertising? What’s the term used for this method and what does it stand for?

- How many impressions are recorded if a single user is served the same ad one thousand times? How many if one thousand users are served the same ad once?

-

Imagine the two scenarios below. Decide which type of campaign would be best for each: text-based CPC advertising or image ads paid for on a CPM basis). Explain your reasoning.

- Netflix is looking to attract new customers by driving traffic to its Web site and increase online subscriptions.

- Zara has just opened a new clothing store in major retailing area in your town. The company doesn’t offer online sales; rather, the majority of its sales come from stores.

- Which firm runs the world’s largest affiliate program? Why is this form of advertising particularly advantageous to the firm (think about the ROI for this sort of effort)?

- Given examples where in-game advertising might work and those where it might be less desirable. List key reasons why in-game advertising has not be as successful as other forms Internet-distributed ads.

8.7 Customer Profiling and Behavioral Targeting

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Be familiar with various tracking technologies and how they are used for customer profiling and ad targeting.

- Understand why customer profiling is both valuable and controversial.

- Recognize steps that organizations can take to help ease consumer and governmental concerns.

Advertisers are willing to pay more for ads that have a greater chance of reaching their target audience, and online firms have a number of targeting tools at their disposal. Much of this targeting occurs whenever you visit a Web site, where a behind-the-scenes software dialog takes place between Web browser and Web server that can reveal a number of pieces of information, including IP address, the type of browser used, the computer type, its operating system, and unique identifiers, called cookiesA line of identifying text, assigned and retrieved by a given Web server and stored in your browser..

And remember, any server that serves you content can leverage these profiling technologies. You might be profiled not just by the Web site that you’re visiting (e.g., nytimes.com), but also by any ad networks that serve ads on that site (e.g., Platform-A, DoubleClick, Google AdSense, Microsoft adCenter).

IP addresses are leveraged extensively in customer profiling. An IP address not only helps with geolocation, it can also indicate a browser’s employer or university, which can be further matched with information such as firm size or industry. IBM has used IP targeting to tailor its college recruiting banner ads to specific schools, for example, “There Is Life After Boston College, Click Here to See Why.” That campaign garnered click-through rates ranging from 5 to 30 percentM. Moss, “These Web Sites Know Who You Are,” ZDNet UK, October 13, 1999. compared to average rates that are currently well below 1 percent for untargeted banner ads. DoubleClick once even served a banner that include a personal message for an executive at then-client Modem Media. The ad, reading “Congratulations on the twins, John Nardone,” was served across hundreds of sites, but was only visible from computers on the Modem Media corporate network.M. Moss, “These Web Sites Know Who You Are,” ZDNet UK, October 13, 1999.

The ability to identify a surfer’s computer, browser, or operating system can also be used to target tech ads. For example, Google might pitch its Chrome browser to users detected running Internet Explorer, Firefox, or Safari; while Apple could target those “I’m a Mac” ads just to Windows users.

But perhaps the greatest degree of personalization and targeting comes from cookies. Visit a Web site for the first time, and in most cases, a behind-the-scenes dialog takes place that goes something like this:

Server: Have I seen you before?

Browser: No.

Server: Then take this unique string of numbers and letters (called a cookie). I’ll use it to recognize you from now on.

The cookie is just a line of identifying text assigned and retrieved by a given Web server and stored in your browser. Upon accepting this cookie your browser has been tagged, like an animal. As you surf around the firm’s Web site, that cookie can be used to build a profile associated with your activities. If you’re on a portal like Yahoo! you might type in your zip code, enter stocks that you’d like to track, and identify the sports teams you’d like to see scores for. The next time you return to the Web site, your browser responds to the server’s “Have I see you before?” question with the equivalent of “Yes, you know me,” and it presents the cookie that the site gave you earlier. The site can then match this cookie against your browsing profile, showing you the weather, stock quotes, sports scores, and other info that it thinks you’re interested in.

Cookies are used for lots of purposes. Retail Web sites like Amazon use cookies to pay attention to what you’ve shopped for and bought, tailoring Web sites to display products that the firm suspects you’ll be most interested in. Sites also use cookies to keep track of what you put in an online “shopping cart,” so if you quit browsing before making a purchase, these items will reappear the next time you visit. And many Web sites also use cookies as part of a “remember me” feature, storing user IDs and passwords. Beware this last one! If you check the “remember me” box on a public Web browser, the next person who uses that browser is potentially using your cookie, and can log in as you!

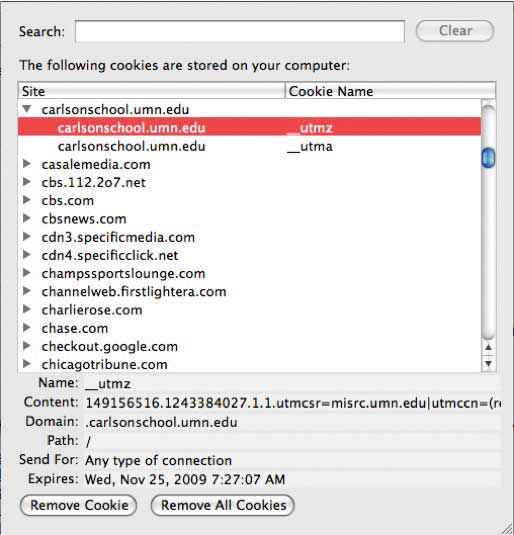

An organization can’t read cookies that it did not give you. So businessweek.com can’t tell if you’ve also got cookies from forbes.com. But you can see all of the cookies in your browser. Take a look and you’ll almost certainly see cookies from dozens of Web sites that you’ve never visited before. These are third-party cookiesSometimes called “tracking cookies” and are served by ad networks or other customer profiling firms. Tracking cookies are used to identify users and record behavior across multiple Web sites. (sometimes called tracking cookies), and they are usually served by ad networks or other customer profiling firms.

Figure 8.15

The Preferences setting in most Web browsers allows you to see its cookies. This browser has received cookies from several ad networks, media sites, and the University of Minnesota Carlson School of Management.

By serving cookies in ads shown on partner sites, ad networks can build detailed browsing profiles that include sites visited, specific pages viewed, duration of visit, and the types of ads you’ve seen and responded to. And that surfing might give an advertising network a better guess at demographics like gender, age, marital status, and more. Visit a new parent site and expect to see diaper ads in the future, even when you’re surfing for news or sports scores!

But What If I Don’t Want a Cookie!

If all of this creeps you out, remember that you’re in control. The most popular Web browsers allow you to block all cookies, block just third-party cookies, purge your cookie file, or even ask for your approval before accepting a cookie. Of course, if you block cookies, you block any benefits that come along with them, and some Web site features may require cookies to work properly. Also note that while deleting a cookie breaks a link between your browser and that Web site, if you supply identifying information in the future (say by logging into an old profile), the site might be able to assign your old profile data to the new cookie.

While the Internet offers targeting technologies that go way beyond traditional television, print, and radio offerings, none of these techniques is perfect. Since users are regularly assigned different IP addresses as they connect and disconnect from various physical and wi-fi networks, IP targeting can’t reliably identify individual users. Cookies also have their weaknesses. They’re assigned by browsers, so if several people use the same browser, all of their Web surfing activity may be mixed into the same cookie profile. Some users might also use different browsers on the same machine, or use different computers. Unless a firm has a way to match up these different cookies with user accounts or other user-identifying information, a site may be working with multiple, incomplete profiles.

Key Takeaways

- The communication between Web browser and Web server can identify IP address, the type of browser used, the computer type, its operating system, and can read and assign unique identifiers, called cookies—all of which can be used in customer profiling and ad targeting.

- An IP address not only helps with geolocation; it can also be matched against other databases to identify the organization providing the user with Internet access (such as a firm or university), that organization’s industry, size, and related statistics.

- A cookie is a unique line of identifying text, assigned and retrieved by a given Web server and stored in your browser, that can be used to build a profile associated with your Web activities.

- The most popular Web browsers allow you to block all cookies, block just third-party cookies, purge your cookie file, or even ask for your approval before accepting a cookie.

Questions and Exercises

- Give examples of how the ability to identify a surfer’s computer, browser, or operating system can be used to target tech ads.

- Describe how IBM targeted ad delivery for its college recruiting efforts. What technologies were used? What was the impact on click-through rates?

- What is a cookie? How are cookies used? Is a cookie a computer program? Which firms can read the cookies in your Web browser?

- Does a cookie accurately identify a user? Why or why not?

- What is the danger of checking the “remember me” box on a public Web browser?

- What’s a tracking cookie? What kinds of firms might use these? How are they used?

- How can users restrict cookie use on their Web browsers? What is the downside of blocking cookies?

- Work with a faculty member and join the Google Online Marketing Challenge (held spring of every year—see http://www.google.com/onlinechallenge). Google offers ad credits for student teams to develop and run online ad campaigns for real clients and offers prizes for winning teams. Some of the experiences earned in the Google Challenge can translate to other ad networks as well; and first-hand client experience has helped many students secure jobs, internships, and even start their own businesses.

8.8 Profiling and Privacy

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Understand the privacy concerns that arise as a result of using tracking cookies to build user profiles.

- Be aware of the negative consequences that could result from the misuse of tracking cookies.

- Know the steps Google has taken to demonstrate its sensitivity to privacy issues.

- Know the kinds of user information that Google stores, and the steps Google takes to protect the privacy of that information.

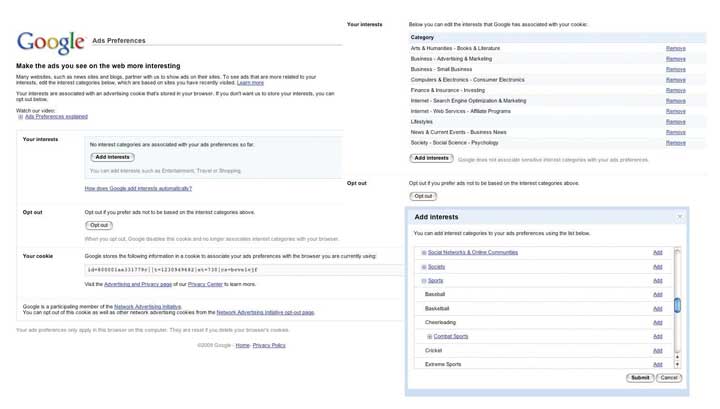

Until 2009, Google hadn’t used tracking cookies on its AdSense network. While AdSense has been wildly successful, contextual advertising has its limits. For example, what kind of useful targeting can firms really do based on the text of a news item on North Korean nuclear testing?R. Singel, “Online Behavioral Targeting Targeted by Feds, Critics,” Wired News, June 3, 2009. So in March 2009, the firm announced what it calls “interest-based ads.” Google AdSense would now issue a third-party cookie and would track browsing activity across AdSense partner sites, and Google-owned YouTube. AdSense would build a profile, initially identifying users within thirty broad categories and six hundred subcategories. Says one Google project manager, “We’re looking to make ads even more interesting.”R. Hof, “Behavioral Targeting: Google Pulls Out the Stops,” BusinessWeek, March 11, 2009.

Figure 8.16 Categories for Google’s Interest-Based Advertising

Of course, there’s a financial incentive to do this too. Ads deemed more interesting should garner more clicks, meaning more potential customer leads for advertisers, more revenue for Web sites that run AdSense, and more money for Google.

But while targeting can benefit Web surfers, users will resist if they feel that they are being mistreated, exploited, or put at risk. Negative backlash might also result in a change in legislation. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission has already called for more transparency and user control in online advertising and for requesting user consent (opt-inProgram (typically a marketing effort) that requires customer consent. This program is contrasted with opt-out programs, which enroll all customers by default.) when collecting sensitive data.R. Singel, “Online Behavioral Targeting Targeted by Feds, Critics,” Wired News, June 3, 2009. Mishandled user privacy could curtail targeting opportunities, limiting growth across the online advertising field. And with less ad support, many of the Internet’s free services could suffer.

Google’s roll-out of interest-based ads shows the firm’s sensitivity to these issues. First, while major rivals have all linked query history to ad targeting, Google steadfastly refuses to do this. Other sites often link registration data (including user-submitted demographics such as gender and age) with tracking cookies, but Google avoids this practice as well.

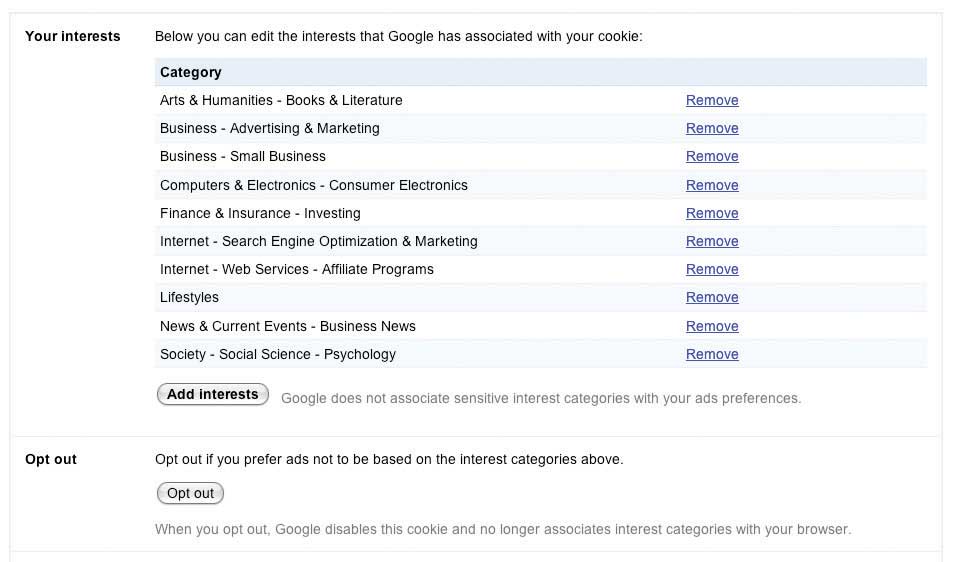

Figure 8.17 Here’s an example of one user’s interests, as tracked by Google’s “Interest-based Ads” and displayed in the firm’s “Ad Preferences Manager.”

Google has also placed significant control in the hands of users, with options at program launch that were notably more robust than those of its competitors.Hansell, 2009. Each interest-based ad is accompanied by an “Ads by Google” link that will bring users to a page describing Google advertising and which provides access to the company’s “Ads Preferences Manager.” This tool allows surfers to see any of the hundreds of potential categorizations that Google has assigned to that browser’s tracking cookie. Users can remove categorizations, and even add interests if they want to improve ad targeting. Some topics are too sensitive to track, and the technology avoids profiling race, religion, sexual orientation, health, political or trade union affiliation, and certain financial categories.R. Mitchell, “What Google Knows about You,” Computerworld, May 11, 2009.

Google also allows users to install a cookie that opts them out of interest-based tracking. And since browser cookies can expire or be deleted, the firm has gone a step further, offering a browser plug-inA small computer program that extends the feature set or capabilities of another application. that will remain permanent, even if a user’s opt-outPrograms that enroll all customer by default, but that allow consumers to discontinue participation if they want to. cookie is purged.

Google, Privacy Advocates, and the Law

Google’s moves are meant to demonstrate transparency in its ad targeting technology, and the firm’s policies may help raise the collective privacy bar for the industry. While privacy advocates have praised Google’s efforts to put more control in the hands of users, many continue to voice concern over what they see as the increasing amount of information that the firm houses.M. Helft, “BITS; Google Lets Users See a Bit of Selves” New York Times, November 9, 2009. For an avid user, Google could conceivably be holding e-mail (Gmail), photos (Picasa), a Web surfing profile (AdSense and DoubleClick), medical records (Google Health), location (Google Latitude), appointments (Google Calendar), transcripts of phone messages (Google Voice), work files (Google Docs), and more.

Google insists that reports portraying it as a data-hording Big Brother are inaccurate. The firm is adamant that user data exists in silos that aren’t federated in any way, nor are employees permitted access to multiple data archives without extensive clearance and monitoring. Data is not sold to third parties. Activities in Gmail, Docs, or most other services isn’t added to targeting profiles. And any targeting is fully disclosed, with users empowered to opt-out at all levels.R. Mitchell, “What Google Knows about You,” Computerworld, May 11, 2009. But critics counter that corporate intensions and data use policies (articulated in a Web site’s Terms of Service) can change over time, and that a firm’s good behavior today is no guarantee of good behavior in the future.R. Mitchell, “What Google Knows about You,” Computerworld, May 11, 2009.