This is “Peer Production, Social Media, and Web 2.0”, chapter 6 from the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems: A Manager's Guide (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 6 Peer Production, Social Media, and Web 2.0

6.1 Introduction

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Recognize the unexpected rise and impact of social media and peer production systems, and understand how these services differ from prior generation tools.

- List the major classifications of social media services.

Over the past few years a fundamentally different class of Internet services has attracted users, made headlines, and increasingly garnered breathtaking market valuations. Often referred to under the umbrella term “Web 2.0A term broadly referring to Internet services that foster collaboration and information sharing; characteristics that distinctly set “Web 2.0” efforts apart from the static, transaction-oriented Web sites of “Web 1.0.” The term is often applied to Web sites and Internet services that foster social media or other sorts of peer production.,” these new services are targeted at harnessing the power of the Internet to empower users to collaborate, create resources, and share information in a distinctly different way from the static Web sites and transaction-focused storefronts that characterized so many failures in the dot-com bubble. Blogs, wikis, social networks, photo and video sharing sites, and tagging systems all fall under the Web 2.0 moniker, as do a host of supporting technologies and related efforts.

The term Web 2.0 is a tricky one because like so many popular technology terms there’s not a precise definition. Coined by publisher and pundit Tim O’Reilly in 2003, techies often joust over the breadth of the Web 2.0 umbrella and over whether Web 2.0 is something new or simply an extension of technologies that have existed since the creation of the Internet. These arguments aren’t really all that important. What is significant is how quickly the Web 2.0 revolution came about, how unexpected it was, and how deeply impactful these efforts have become. Some of the sites and services that have evolved and their Web 1.0 origins are listed in Table 6.1 "Web 1.0 versus Web 2.0".Adapted from T. O’Reilly, “What Is Web 2.0?” O’Reilly, September 30, 2005.

Table 6.1 Web 1.0 versus Web 2.0

| Web 1.0 | Web 2.0 | |

|---|---|---|

| DoubleClick | → | Google AdSense |

| Ofoto | → | Flickr |

| Akamai | → | BitTorrent |

| mp3.com | → | Napster |

| Britannica Online | → | Wikipedia |

| personal Web sites | → | blogging |

| evite | → | upcoming.org and E.V.D.B. |

| domain name speculation | → | search engine optimization |

| page views | → | cost per click |

| screen scraping | → | Web services |

| publishing | → | participation |

| content management systems | → | wikis |

| directories (taxonomy) | → | tagging (“folksonomy”) |

| stickiness | → | syndication |

| instant messaging | → | |

| Monster.com | → |

To underscore the speed with which Web 2.0 arrived on the scene, and the impact of leading Web 2.0 services, consider the following efforts:

- According to a spring 2008 report by Morgan Stanley, Web 2.0 services ranked as seven of the world’s top ten most heavily trafficked Internet sites (YouTube, Live.com, MySpace, Facebook, Hi5, Wikipedia, and Orkut); only one of these sites (MySpace) was on the list in 2005.Morgan Stanley, Internet Trends Report, March 2008.

- With only seven full-time employees and an operating budget of less than one million dollars, Wikipedia has become the Internet’s fifth most visited site on the Internet.G. Kane and R. Fichman, “The Shoemaker’s Children: Using Wikis for Information Systems Teaching, Research, and Publication,” MIS Quarterly, March 2009. The site boasts well over fourteen million articles in over two hundred sixty different languages, all of them contributed, edited, and fact-checked by volunteers.

- Just two years after it was founded, MySpace was bought for $580 million by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation (the media giant that owns the Wall Street Journal and the Fox networks, among other properties). By the end of 2007, the site accounted for some 12 percent of Internet minutes and has repeatedly ranked as the most-visited Web site in the United States.D. Chmielewski and J. Guynn, “MySpace Ready to Prove Itself in Faceoff,” Chicago Tribune, June 8, 2008.

- At rival Facebook, users in the highly sought after college demographic spend over thirty minutes a day on the site. A fall 2007 investment from Microsoft pegged the firm’s overall value at fifteen billion dollars, a number that would make it the fifth most valuable Internet firm, despite annual revenues at the time of only one hundred fifty million dollars.M. Arrington, “Perspective: Facebook Is Now Fifth Most Valuable U.S. Internet Company,” TechCrunch, October 25, 2007.

- Just twenty months after its founding, YouTube was purchased by Google for $1.65 billion. While Google struggles to figure out how to make profitable what is currently a money-losing resource hog (over twenty hours of video are uploaded to YouTube each minute)E. Nakashima, “YouTube Ordered to Release User Data,” Washington Post, July 4, 2008. the site has emerged as the Web’s leading destination for video, hosting everything from apologies from JetBlue’s CEO for service gaffes to questions submitted as part of the 2008 U.S. presidential debates. Fifty percent of YouTube’s roughly three hundred million users visit the site at least once a week.Morgan Stanley, Internet Trends Report, March 2008.

Table 6.2 Major Web 2.0 Tools

| Description | Features | Technology Providers | Use Case Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blogs | Short for “Web log”—an online diary that keeps a running chronology of entries. Readers can comment on posts. Can connect to other blogs through blog rolls or trackbacks. Key uses: Share ideas, obtain feedback, mobilize a community. |

|

|

Corporate Users:

|

| Wikis | A Web site that anyone can edit directly from within the browser. Key uses: Collaborate on common tasks or to create a common knowledge base. |

|

|

Corporate Users:

|

| Electronic Social Network | Online community that allows users to establish a personal profile, link to other profiles (i.e., friends), and browse the connections of other, and communicate with members via messaging, posts, et cetera.

Key Uses:

|

|

|

Corporate Users:

|

| Microblogging | Short, asynchronous messaging system. Users send messages to “followers.” Key Uses: distributing time, sensitive information, sharing opinions, virally spreading ideas, running contests and promotions, soliciting feedback, providing customer support, tracking commentary on firms/products/issues, organizing protests. |

|

|

Corporate Users:

|

Millions of users, billions of dollars, huge social impact, and these efforts weren’t even on the radar of most business professionals when today’s graduating college seniors first enrolled as freshmen. The trend demonstrates that even some of the world’s preeminent thought leaders and business publications can be sideswiped by the speed of the Internet.

Consider that when management guru Michael Porter wrote a piece titled, “Strategy and the Internet” at the end of the dot-com bubble, he lamented the high cost of building brand online, questioned the power of network effects, and cast a skeptical eye on ad-supported revenue models. Well, it turns out Web 2.0 efforts challenged all of these assumptions. Among the efforts above, all built brand on the cheap with little conventional advertising, and each owes their hypergrowth and high valuation to their ability to harness the network effect. In June, 2008, BusinessWeek also confessed to having an eye off the ball. In a cover story on social media, the magazine offered a mea culpa, confessing that while blogging was on their radar, editors were blind to the bigger trends afoot online, and underestimated the rise and influence of social networks, wikis, and other efforts.Stephen Baker and Heather Green, “Beyond Blogs: What Every Business Needs to Know,” BusinessWeek, June 2, 2008.

While the Web 2.0 moniker is a murky one, we’ll add some precision to our discussion of these efforts by focusing on peer productionWhen users collaboratively work to create content and provide services online. Includes social media sites, as well as peer-produced services, such as Skype and BitTorrent, where the participation of users provide the infrastructure and computational resources that enable the service., perhaps Web 2.0’s most powerful feature, where users work, often collaboratively, to create content and provide services online. Web-based efforts that foster peer production are often referred to as social mediaContent that is created, shared, and commented on by a broader community of users. Services that support the production and sharing of social media include blogs, wikis, video sites like YouTube, and most social networks. or user-generated content sites. These sites include blogs; wikis; social networks like Facebook and MySpace; communal bookmarking and tagging sites like Del.icio.us; media sharing sites like YouTube and Flickr; and a host of supporting technologies. And it’s not just about media. Peer-produced services like Skype and BitTorrent leverage users’ computers instead of a central IT resource to forward phone calls and video. This ability saves their sponsors the substantial cost of servers, storage, and bandwidth. Techniques such as crowdsourcing, where initially undefined groups of users band together to solve problems, create code, and develop services, are also a type of peer production. These efforts will be expanded on below, along with several examples of their use and impact.

Key Takeaways

- A new generation of Internet applications is enabling consumers to participate in creating content and services online. Examples include Web 2.0 efforts such as social networks, blogs, and wikis, as well as efforts such as Skype and BitTorret, which leverage the collective hardware of their user communities to provide a service.

- These efforts have grown rapidly, most with remarkably little investment in promotion. Nearly all of these new efforts leverage network effects to add value and establish their dominance and viral marketing to build awareness and attract users.

- Experts often argue whether Web 2.0 is something new or merely an extension of existing technologies. The bottom line is the magnitude of the impact of the current generation of services.

- Network effects play a leading role in enabling Web 2.0 firms. Many of these services also rely on ad-supported revenue models.

Questions and Exercises

- What distinguishes Web 2.0 technologies and services from the prior generation of Internet sites?

- Several examples of rapidly rising Web 2.0 efforts are listed in this section. Can you think of other dramatic examples? Are there cautionary tales of efforts that may not have lived up to their initial hype or promise? Why do you suppose they failed?

- Make your own list of Web 1.0 and Web 2.0 services and technologies. Would you invest in them? Why or why not?

- In what ways do Web 2.0 efforts challenge the assumptions that Michael Porter made regarding Strategy and the Internet?

6.2 Blogs

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Know what blogs are and how corporations, executives, individuals, and the media use them.

- Understand the benefits and risks of blogging.

- Appreciate the growth in the number of blogs, their influence, and their capacity to generate revenue.

BlogsOnline journal entries, usually made in a reverse chronological order. Blogs typically provide comment mechanisms where users can post feedback for authors and other readers. (short for Web logs) first emerged almost a decade ago as a medium for posting online diaries. (In a perhaps apocryphal story, Wired magazine claimed the term “Web log” was coined by Jorn Barger, a sometimes homeless, yet profoundly prolific, Internet poster). From humble beginnings, the blogging phenomenon has grown to a point where the number of public blogs tracked by Technorati (the popular blog index) has surpassed one hundred million.D. Takahashi, “Technorati Releases Data on State of the Blogosphere: Bloggers of the World Have United,” VentureBeat, September 28, 2008. This number is clearly a long tailIn this context, refers to an extremely large selection of content or products. The long tail is a phenomenon whereby firms can make money by offering a near-limitless selection. phenomenon, loaded with niche content that remains “discoverable” through search engines and blog indexes. TrackbacksLinks in a blog post that refer eaders back to cited sources. Trackbacks allow a blogger to see which and how many other bloggers are referring to their content. A “trackback” field is supported by most blog software and while it’s not required to enter a trackback when citing another post, it’s considered good “netiquette” to do so. (third-party links back to original blog post), and blog rollsA list of a blogger’s favorite blogs. While not all blogs include blog rolls, those that do are often displayed on the right or left column of a blog’s main page. (a list of a blogger’s favorite sites—a sort of shout-out to blogging peers) also help distinguish and reinforce the reputation of widely read blogs.

The most popular blogs offer cutting-edge news and commentary, with postings running the gamut from professional publications to personal diaries. While this cacophony of content was once dismissed, blogging is now a respected and influential medium. Consider that the political blog The Huffington Post is now more popular than all but eight newspaper sites and has a valuation higher than many publicly traded papers.E. Alterman, “Out of Print, the Death and Life of the American Newspaper,” New Yorker, March 31, 2008; and M. Learmonth, “Huffington Post More Valuable Than Some Newspaper Cos.,” DigitalNext, December 1, 2008. Keep in mind that this is a site without the sports, local news, weather, and other content offered by most papers. Ratings like this are hard to achieve—most bloggers can’t make a living off their musings. But among the elite ranks, killer subscriber numbers are a magnet for advertisers. Top blogs operating on shoestring budgets can snare several hundred thousand dollars a month in ad revenue.S. Zuckerman, “Yes, Some Blogs Are Profitable—Very Profitable,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 21, 2007. Most start with ad networks like Google AdSense, but the most elite engage advertisers directly for high-value deals and extended sponsorships.

Top blogs have begun to attract well-known journalists away from print media. The Huffington Post hired a former Washington Post editor Lawrence Roberts to head the site’s investigative unit. The popular blog TechCrunch hired Erick Schonfeld away from Time Warner’s business publishing empire, while Schonfeld’s cohort Om Malik founded another highly ranked tech industry blog, GigaOM. And sometimes this drift flows the other direction. Robert Scoble, a blogger who made his reputation as the informal online voice for Microsoft, was hired to run social media at Fast Company magazine.

Senior executives from many industries have also begun to weigh in with online ruminations, going directly to the people without a journalist filtering their comments. Sun Microsystem’s Jonathan Schwartz, GM’s Bob Lutz, and Paul Levy (CEO of healthcare quality leader Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) use their blogs for purposes that include a combination of marketing, sharing ideas, gathering feedback, press response, and image shaping. Blogs have the luxury of being more topically focused than traditional media, with no limits on page size, word count, or publication deadline. Some of the best examples engage new developments in topic domains much more quickly and deeply than traditional media. For example, it’s not uncommon for blogs focused on the law or politics to provide a detailed dissection of a Supreme Court opinion within hours of its release—offering analysis well ahead of, and with greater depth, than via what bloggers call the mainstream media (MSM)Refers to newspapers, magazine, television, and radio. The MSM is distinctly different from Internet media such as blogs.. As such, it’s not surprising that most mainstream news outlets have begun supplementing their content with blogs that can offer greater depth, more detail, and deadline-free timeliness.

Blogs

While the feature set of a particular blog depends on the underlying platform and the preferences of the blogger, several key features are common to most blogs:

- Ease of use. Creating a new post usually involves clicking a single button.

- Reverse chronology. Posts are listed in reverse order of creation, making it easy to see the most recent content.

- Comment threads. Readers can offer comments on posts.

- Persistence. Posts are maintained indefinitely at locations accessible by permanent links.

- Searchability. Current and archived posts are easily searchable.

- Tags. Posts are often classified under an organized tagging scheme.

- Trackbacks. Allows an author to acknowledge the source of an item in their post, which allows bloggers to follow the popularity of their posts among other bloggers.

The voice of the blogosphereA term referring to the collective community of bloggers, as well as those who read and comment on blogs. can wield significant influence. Examples include leading the charge for Dan Rather’s resignation and prompting the design of a new insulin pump. In an example of what can happen when a firm ignores social media, consider the flare-up Ingersoll Rand faced when the online community exposed a design flaw in its Kryptonite bike lock.

Online posts showed the thick metal lock could be broken with a simple ball-point pen. A video showing the hack was posted online. When Ingersoll Rand failed to react quickly, the blogosphere erupted with criticism. Just days after online reports appeared, the mainstream media picked up the story. The New York Times ran a story titled “The Pen Is Mightier Than the Lock” that included a series of photos demonstrating the ballpoint Kryptonite lock pick. The event tarnished the once-strong brand and eventually resulted in a loss of over ten million dollars.

Concern over managing a firm’s online reputation by monitoring blog posts and other social media commentary has led to the rise of an industry known as online reputation managementThe process of tracking and responding to online mentions of a product, organization, or individual. Services supporting online reputation management range from free Google Alerts to more sophisticated services that blend computer-based and human monitoring of multiple media channels.. Firms specializing in this field will track a client firm’s name, brand, executive names, or other keywords and report online activity and whether it is positive or negative

Like any Web page, blogs can be public, tucked behind a corporate firewall, or password protected. Most blogs offer a two-way dialog, allowing users to comment on posts (sort of instant “letters to the editor,” posted online and delivered directly to the author). The running dialog can read like an electronic bulletin board, and can be an effective way to gather opinion when vetting ideas. Just as important, user comments help keep a blogger honest. Just as the “wisdom of crowds” keeps Wikipedia accurate, a vigorous community of commenters will quickly expose a blogger’s errors of fact or logic.

Despite this increased popularity, blogging has its downside. Blog comments can be a hothouse for spam and the disgruntled. Ham-handed corporate efforts (such as poor response to public criticism or bogus “praise posts”) have been ridiculed. Employee blogging can be difficult to control and public postings can “live” forever in the bowels of an Internet search engine or as content pasted on other Web sites. Many firms have employee blogging and broader Internet posting policies to guide online conduct that may be linked to the firm. Bloggers beware—there are dozens of examples of workers who have been fired for what employers viewed as inappropriate posts.

Blogs can be hosted via third-party services (Google Blogger, WordPress.com, TypePad, Windows Live Spaces), with most offering a combination of free and premium features. Blogging features have also been incorporated into social networks such as Facebook, MySpace, and Ning, as well as wiki tools such as SocialText. Blogging software can also be run on third-party servers, allowing the developer more control in areas such as security and formatting. The most popular platform for users choosing to host their own blog server is the open source Word Press system (based on PHP and MySQL).

Blogs have become a fire hose of rapidly delivered information as tool providers have made it easier for would-be bloggers to capture and post content. For example, the Google Toolbar has a “BlogThis!” feature that allows anyone with a Google Blogger account to post links directly to their blogs. Apple ships blog hosting tools with its server products, and Microsoft offers the free LiveWriter blog editing tool and the Windows Spaces blogging service. Blogger and many social networking sites also offer easy features for posting content and photos from a mobile phone or devices like the iPod Touch.

In the end, the value of any particular blog derives from a combination of technical and social features. The technical features make it easy for a blogger and his or her community to engage in an ongoing conversation on some topic of shared interest. But the social norms and patterns of use that emerge over time in each blog are what determine whether technology features will be harnessed for good or ill. Some blogs develop norms of fairness, accuracy, proper attribution, quality writing, and good faith argumentation, and attract readers that find these norms attractive. Others mix it up with hotly contested debate, one-sided partisanship, or deliberately provocative posts, attracting a decidedly different type of discourse.

Key Takeaways

- Blogs provide a rapid way to distribute ideas and information from one writer to many readers.

- Ranking engines, trackbacks, and comments allow a blogger’s community of readers to spread the word on interesting posts and participate in the conversation, and help distinguish and reinforce the reputations of widely read blogs.

- Well-known blogs can be powerfully influential, acting as flashpoints on public opinion.

- Firms ignore influential bloggers at their peril, but organizations should also be cautious about how they use and engage blogs, and avoid flagrantly promotional or biased efforts.

- Top blogs have gained popularity, valuations, and profits that far exceed those of many leading traditional newspapers, and leading blogs have begun to attract well-known journalists away from print media.

- Senior executives from several industries use blogs for business purposes including marketing, sharing ideas, gathering feedback, press response, and image shaping.

Questions and Exercises

- Visit Technorati and find out which blogs are currently the most popular. Why do you suppose the leaders are so popular?

- How are popular blogs discovered? How is their popularity reinforced?

- Are blog comment fields useful? If so, to whom or how? What is the risk associated with allowing users to comment on blog posts? How should a blogger deal with comments that they don’t agree with?

- Why would a corporation, an executive, a news outlet, or a college student want to blog? What are the benefits? What are the concerns?

- Identify firms and executives that are blogging online. Bring examples to class and be prepared to offer your critique of their efforts.

- How do bloggers make money? Do all bloggers have to make money?

- According to your reading, how does the blog The Huffington Post compare with the popularity of newspaper Web sites?

- What advantage do blogs have over the MSM? What advantage does the MSM have over the most popular blogs?

- Start a blog using Blogger.com, WordPress.com, or some other blogging service. Post a comment to another blog. Look for the trackback field when making a post, and be sure to enter the trackback for any content you cite in your blog.

6.3 Wikis

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Know what wikis are and how they are used by corporations and the public at large.

- Understand the technical and social features that drive effective and useful wikis.

- Be able to suggest opportunities where wikis would be useful and consider under what circumstances their use may present risks.

- Recognize how social media such as wikis and blogs can influence a firm’s customers and brand.

A wikiA Web site that can be modified by anyone, from directly within a Web browser (provided that user is granted edit access). is a Web site anyone can edit directly within a Web browser (provided the site grants the user edit access). Wikis derive their name from the Hawaiian word for “quick.” Ward Cunningham, the “wiki father” christened this new class of software with the moniker in honor of the wiki-wiki shuttle bus at the Honolulu airport. Wikis can indeed be one of the speediest ways to collaboratively create content online. Many popular online wikis serve as a shared knowledge repository in some domain.

The largest and most popular wiki is Wikipedia, but there are hundreds of publicly accessible wikis that anyone can participate in. Each attempts to chronicle a world of knowledge within a particular domain, with examples ranging from Wine Wiki for oenophiles to Wookieepedia, the Star Wars wiki. But wikis can be used for any collaborative effort—from meeting planning to project management. And in addition to the hundreds of public wikis, there are many thousand more that are hidden away behind firewalls, used as proprietary internal tools for organizational collaboration.

Like blogs, the value of a wiki derives from both technical and social features. The technology makes it easy to create, edit, and refine content; learn when content has been changed, how and by whom; and to change content back to a prior state. But it is the social motivations of individuals (to make a contribution, to share knowledge) that allow these features to be harnessed. The larger and more active a wiki community, the more likely it is that content will be up-to-date and that errors will be quickly corrected. Several studies have shown that large community wiki entries are as or more accurate than professional publication counterparts.

Want to add to or edit a wiki entry? On most sites you just click the Edit link. Wikis support what you see is what you get (WYSIWYG)A phrase used to describe graphical editing tools, such as those found in a wiki, page layout program, or other design tool. editing that, while not as robust as traditional word processors, is still easy enough for most users to grasp without training or knowledge of arcane code or markup language. Users can make changes to existing content and can easily create new pages or articles and link them to other pages in the wiki. Wikis also provide a version history. Click the “history” link on Wikipedia, for example, and you can see when edits were made and by whom. This feature allows the community to roll backThe ability to revert a wiki page to a prior version. This is useful for restoring earlier work in the event of a posting error, inaccuracy, or vandalism. a wiki to a prior page, in the event that someone accidentally deletes key info, or intentionally defaces a page.

Vandalism is a problem on Wikipedia, but it’s more of a nuisance than a crisis. A Wired article chronicled how Wikipedia’s entry for former U.S. President Jimmy Carter was regularly replaced by a photo of a “scruffy, random unshaven man with his left index finger shoved firmly up his nose.”Daniel Pink, “The Book Stops Here,” Wired, March 2005. Nasty and inappropriate, to be sure, but the Wikipedia editorial community is now so large and so vigilant that most vandalism is caught and corrected within seconds. Watch-lists for the most active targets (say the Web pages of political figures or controversial topics) tip off the community when changes are made. The accounts of vandals can be suspended, and while mischief-makers can log in under another name, most vandals simply become discouraged and move on. It’s as if an army of do-gooders follows a graffiti tagger and immediately repaints any defacement.

Wikis

As with blogs, a wiki’s features set varies depending on the specific wiki tool chosen, as well as administrator design, but most wikis support the following key features:

- All changes are attributed, so others can see who made a given edit.

- A complete revision history is maintained so changes can be compared against prior versions and rolled back as needed.

- There is automatic notification and monitoring of updates; users subscribe to wiki content and can receive updates via e-mail or RSS feed when pages have been changed or new content has been added.

- All the pages in a wiki are searchable.

- Specific wiki pages can be classified under an organized tagging scheme.

Wikis are available both as software (commercial as well as open source varieties) that firms can install on their own computers or as online services (both subscription or ad-supported) where content is hosted off site by third parties. Since wikis can be started without the oversight or involvement of a firm’s IT department, their appearance in organizations often comes from grassroots user initiative. Many wiki services offer additional tools such as blogs, message boards, or spreadsheets as part of their feature set, making most wikis really more full-featured platforms for social computing.

Examples of Wiki Use

Wikis can be vital tools for collecting and leveraging knowledge that would otherwise be scattered throughout an organization; reducing geographic distance; removing boundaries between functional areas; and flattening preexisting hierarchies. Companies have used wikis in a number of ways:

- At Pixar, all product meetings have an associated wiki to improve productivity. The online agenda ensures that all attendees can arrive knowing the topics and issues to be covered. Anyone attending the meeting (and even those who can’t make it) can update the agenda, post supporting materials, and make comments to streamline and focus in-person efforts.

- At European investment bank Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein, employees use wikis for everything from setting meeting agendas to building multimedia training for new hires. Six months after launch, wiki use had surpassed activity on the firm’s established intranet. Wikis are also credited with helping to reduce Dresdner e-mail traffic by 75 percent.Dan Carlin, “Corporate Wikis Go Viral,” BusinessWeek, March 12, 2007.

- Sony’s PlayStation team uses wikis to regularly maintain one-page overviews on the status of various projects. In this way, legal, marketing, and finance staff can get quick, up-to-date status reports on relevant projects, including the latest projected deadlines, action items, and benchmark progress. Strong security measures are enforced that limit access to only those who must be in the know, since the overviews often discuss products that have not been released.

- Employees at investment-advisory firm Manning and Napier use a wiki to collaboratively track news in areas of critical interest. Providing central repositories for employees to share articles and update evolving summaries on topics such as universal health care legislation, enables the firm to collect and focus what would otherwise be fragmented findings and insight. Now all employees can refer to central pages that each serve as a lightning rod attracting the latest and most relevant findings.

When brought outside the firewall, corporate wikis can also be a sort of value-generation greenhouse, allowing organizations to leverage input from their customers and partners:

- Amazon leverages its Amapedia wiki, allowing customers to create user-generated product information and side-by-side review comparisons.

- eBay, a site that has regularly been shaped by user input through bulletin-board forums, now provides a wiki where users can collectively create articles on any topic of interest to the community, including sales strategy, information for collectable enthusiasts, or new user documentation.

- Microsoft leveraged its customer base to supplement documentation for its Visual Studio software development tool. The firm was able to enter the Brazilian market with Visual Studio in part because users had created product documentation in Portuguese.Rachel King, “No Rest for the Wiki,” BusinessWeek, March 12, 2007.

- ABC and CBS have created public wikis for the television programs Lost, The Amazing Race, and CSI, among others, offering an outlet for fans, and a way for new viewers to catch up on character backgrounds and complex plot lines.

- Executive Travel, owned by American Express Publishing, has created a travel wiki for its more than one hundred and thirty thousand readers with the goal of creating what it refers to as “a digital mosaic that in theory is more authoritative, comprehensive, and useful” than comments on a Web site, and far more up-to-date than any paper-based travel guide.Rachel King, “No Rest for the Wiki,” BusinessWeek, March 12, 2007. Of course, one challenge in running such a corporate effort is that there may be a competing public effort already in place. Wikitravel.org currently holds the top spot among travel-based wikis, and network effects suggest it will likely grow and remain more current than rival efforts.

Jump-starting a wiki can be a challenge, and an underused wiki can be a ghost town of orphan, out-of-date, and inaccurate content. Fortunately, once users see the value of wikis, use and effectiveness often snowballs. The unstructured nature of wikis are also both a strength and weakness. Some organizations employ wikimastersIndividuals often employed by organizations to review community content in order to delete excessive posts, move commentary to the best location, and edit as necessary. to “garden” community content; “prune” excessive posts, “transplant” commentary to the best location, and “weed” as necessary. Often communities will quickly develop norms for organizing and maintaining content. Wikipatterns.com offers a guide to the stages of wiki adoption and a collection of community-building and content-building strategies.

Don’t Underestimate the Power of Wikipedia

Not only is the nonprofit Wikipedia, with its enthusiastic army of unpaid experts and editors, an immediate threat to the three-hundred-year-old Encyclopedia Britannica, Wikipedia entries can impact nearly all large-sized organizations. Wikipedia is the go-to, first-choice reference site for a generation of “netizens,” and Wikipedia entries are invariably one of the top links, often the first link, to appear in Internet search results.

This position means that anyone from top executives to political candidates to any firm large enough to warrant an entry has to contend with the very public commentary offered up in a Wikipedia entry. In the same way that firms monitor their online reputations in blog posts and Twitter tweets, they’ve also got to keep an eye on wikis.

But firms that overreach and try to influence an entry outside of Wikipedia’s mandated neutral point of view (NPOV)An editorial style that is free of bias and opinion. Wikipedia norms dictate that all articles must be written in NPOV., risk a backlash and public exposure. Version tracking means the wiki sees all. Users on computers at right-leaning Fox News were embarrassingly caught editing the wiki page of the lefty pundit and politician Al Franken (a nemesis of Fox’s Bill O’Reilly);A. Bergman, “Wikipedia Is Only as Anonymous as your I.P.,” O’Reilly Radar, August 14, 2007. Sony staffers were flagged as editing the entry for the Xbox game Halo 3;I. Williams, “Sony Caught Editing Halo 3 Wikipedia Entry,” Vnunet.com, September 5, 2007. and none other than Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales was criticized for editing his own Wikipedia biography;E. Hansen, “Wikipedia Founder Edits Own Bio,” Wired, December 19, 2005. an act that some consider bad online form at best, and dishonest at worst.

One last point on using Wikipedia for research. Remember that according to its own stated policies, Wikipedia isn’t an original information source; rather, it’s a clearinghouse for verified information. So citing Wikipedia as a reference usually isn’t considered good form. Instead, seek out original (and verifiable) sources via the links at the bottom of Wikipedia entries.

Key Takeaways

- Wikis can be powerful tools for many-to-many content collaboration, and can be ideal for creating resources that benefit from the input of many such as encyclopedia entries, meeting agendas, and project status documents.

- The greater the number of wiki users, the more likely the information contained in the wiki will be accurate and grow in value.

- Wikis can be public or private.

- The availability of free or low-cost wiki tools can create a knowledge clearinghouse on topics, firms, products, and even individuals. Organizations can seek to harness the collective intelligence (wisdom of the crowds) of online communities. The openness of wikis also act as a mechanism for promoting organizational transparency and accountability.

Questions and Exercises

- Visit a wiki, either an established site like Wikipedia, or a wiki service like SocialText. Make an edit to a wiki entry or use a wiki service to create a new wiki for your own use (e.g., for a class team to use in managing a group project). Be prepared to share your experience with the class.

- What factors determine the value of a wiki? Which key concept, first introduced in Chapter 2 "Strategy and Technology", drives a wiki’s success?

- If anyone can edit a wiki, why aren’t more sites concerned about vandalism, inaccurate, or inappropriate content? Are there technical reasons not to be concerned? Are there “social” reasons that can alleviate concern?

- Give examples of corporate wiki use, as well as examples where firms used wikis to engage their customers or partners. What is the potential payoff of these efforts? Are there risks associated with these efforts?

- Do you feel that you can trust content in wikis? Do you feel this content is more or less reliable than content in print encyclopedias? Than the content in newspaper articles? Why?

- Have you ever run across an error in a wiki entry? Describe the situation.

- Is it ethical for a firm or individual to edit their own Wikipedia entry? Under what circumstances would editing a Wikipedia entry seem unethical to you? Why? What are the risks a firm or individual is exposed to when making edits to public wiki entries? How do you suppose individuals and organizations are identified when making wiki edits?

- Would you cite Wikipedia as a reference when writing a paper? Why or why not?

6.4 Electronic Social Networks

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Know what social networks are, be able to list key features, and understand how they are used by individuals, groups, and corporations.

- Understand the difference between major social networks MySpace, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

- Recognize the benefits and risks of using social networks.

- Be aware of trends that may influence the evolution of social networks.

Social networksAn online community that allows users to establish a personal profile and communicate with others. Large public social networks include MySpace, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Google’s Orkut. have garnered increasing attention as established networks grow and innovate, new networks emerge, and value is demonstrated. MySpace signed a billion-dollar deal to carry ads from Google’s AdSense network. Meanwhile, privately held Facebook has moved beyond its college roots, and opened its network to third-party application developers. LinkedIn, which rounds out the Big Three U.S. public social networks, has grown to the point where its influence is threatening recruiting sites like Monster.com and CareerBuilder.M. Boyle, “Recruiting: Enough to Make a Monster Tremble,” BusinessWeek, June 25, 2009. It now offers services for messaging, information sharing, and even integration with the BusinessWeek Web site.

Media reports often mention MySpace, Facebook, and LinkedIn in the same sentence. However, while these networks share some common features, they serve very different purposes. MySpace pages are largely for public consumption. The site was originally started by musicians as a tool to help users discover new music and engage with bands. Today, MySpace members leverage the service to discover people with similar tastes or experiences (say fans of a comic, or sufferers of a condition).

Facebook, by contrast, is more oriented towards reinforcing existing social ties between people who already know each other. This difference leads to varying usage patterns. Since Facebook is perceived by users as relatively secure, with only invited “friends” seeing your profile, over a third of Facebook users post their mobile phone numbers on their profile pages.

LinkedIn was conceived from the start as a social network for business users. The site’s profiles act as a sort of digital Rolodex that users update as they move or change jobs. Users can pose questions to members of their network, engage in group discussions, ask for introductions through mutual contacts, and comment on others’ profiles (e.g., recommending a member).

Active members find the site invaluable for maintaining professional contacts, seeking peer advice, networking, and even recruiting. Carmen Hudson, Starbucks manager of enterprise staffing, states LinkedIn is “one of the best things for finding midlevel executives.”Rachel King, “No Rest for the Wiki,” BusinessWeek, March 12, 2007. Such networks are also putting increasing pressure on firms to work particularly hard to retain top talent. While once HR managers fiercely guarded employee directories for fear that a list of talent may fall into the hands of rivals, today’s social networks make it easy for anyone to gain a list of a firm’s staff, complete with contact information.

While these networks dominate in the United States, the network effect and cultural differences work to create islands where other social networks are favored by a particular culture or region. The first site to gain traction in a given market is usually the winner. Google’s Orkut, Bebo (now owned by AOL), and Cyworld have small U.S. followings, but are among the largest sites in Brazil, Europe, and South Korea. Research by Ipsos Insight also suggests that users in many global markets, including Brazil, South Korea, and China, are more active social networkers than their U.S. counterparts.Ipsos Insights, Online Video and Social Networking Web Sites Set to Drive the Evolution of Tomorrow’s Digital Lifestyle Globally, July 5, 2007.

Perhaps the most powerful (and controversial) feature of most social networks is the feedAn update on an individual’s activities that are broadcast to a member’s contacts or “friends.” Feeds may include activities such as posting messages, photos, or video, joining groups, or installing applications. (or newsfeed). Pioneered by Facebook but now adopted by most services, feeds provide a timely update on the activities of people or topics that an individual has an association with. Facebook feeds can give you a heads up when someone makes a friend, joins a group, posts a photo, or installs an application.

Feeds are inherently viralIn this context, information or applications that spread rapidly between users.. By seeing what others are doing on a social network, feeds can rapidly mobilize populations and dramatically spread the adoption of applications. Leveraging feeds, it took just ten days for the Facebook group Support the Monks’ Protest in Burma to amass over one hundred and sixty thousand Facebook members. Feeds also helped music app iLike garner three million Facebook users just two weeks after its launch.Sarah Lacy, Once You’re Lucky, Twice You’re Good: The Rebirth of Silicon Valley and the Rise of Web 2.0 (New York: Gotham Books, 2008); and K. Nicole, “iLike Sees Exponential Growth with Facebook App,” Mashable, June 11, 2007. Its previous Web-based effort took eight months to reach those numbers.

But feeds are also controversial. Many users react negatively to this sort of public broadcast of their online activity, and feed mismanagement can create public relations snafus, user discontent, and potentially open up a site to legal action. Facebook initially dealt with a massive user outcry at the launch of feeds, and faced a subsequent backlash when its Beacon service broadcast user purchases without first explicitly asking their permission (see Chapter 7 "Facebook: Building a Business from the Social Graph" for more details).

Social Networks

The foundation of a social network is the user profile, but utility goes beyond the sort of listing found in a corporate information directory. Typical features of a social network include support for the following:

- Detailed personal profiles

- Affiliations with groups, such as alumni, employers, hobbies, fans, health conditions)

- Affiliations with individuals (e.g., specific “friends”)

- Private messaging and public discussions

- Media sharing (text, photos, video)

- “Feeds” of recent activity among members (e.g., status changes, new postings, photos, applications installed)

- The ability to install and use third-party applications tailored to the service (games, media viewers, survey tools, etc.), many of which are also social and allow others to interact.

Corporate Use of Social Networks

The use of public social networks within private organizations is becoming widespread. Many employees have organized groups using publicly available social networking sites because similar tools are not offered by their firms. Workforce Management reported that MySpace had over forty thousand groups devoted to companies or coworkers, while Facebook had over eight thousand.Ed Frauenheim, “Social Revolution,” Workforce Management, October 2007. Assuming a large fraction of these groups are focused on internal projects, this demonstrates a clear pent up demand for corporate-centric social networks.

Many firms are choosing to meet this demand by implementing internal social network platforms that are secure and tailored to firm needs. At the most basic level, these networks have supplanted the traditional employee directory. Social network listings are easy to update and expand. Employees are encouraged to add their own photos, interests, and expertise to create a living digital identity.

Firms such as Deloitte, Dow Chemical, and Goldman Sachs have created social networks for “alumni” who have left the firm or retired. These networks can be useful in maintaining contacts for future business leads, rehiring former employees (20 percent of Deloitte’s experienced hires are so called “boomerangs,” or returning employees), or recruiting retired staff to serve as contractors when labor is tight.Rachel King, “Social Networks: Execs Use Them Too,” BusinessWeek, November 11, 2006. Maintaining such networks will be critical in industries like I.T. and health care that are likely to be plagued by worker shortages for years to come.

Social networking can also be important for organizations like IBM, where some 42 percent of employees regularly work from home or client locations. IBM’s social network makes it easier to locate employee expertise within the firm, organize virtual work groups, and communicate across large distances.W. Bulkley, “Playing Well with Others,” Wall Street Journal, June 18, 2007. As a dialogue catalyst, a social network transforms the public directory into a front of knowledge sharing that promotes organization flattening and value-adding expertise sharing.

As another example of corporate social networks, Reuters has rolled out Reuters Space, a private online community for financial professionals. Profile pages can also contain a personal blog and news feeds (from Reuters or external services). Every profile page is accessible to the entire Reuters Space community, but members can choose which personal details are available to whom. While IBM and Reuters have developed their own social network platforms, firms are increasingly turning to third-party vendors like SelectMinds (adopted by Deloitte, Dow Chemical, and Goldman Sachs) and LiveWorld (adopted by Intuit, eBay, the NBA, and Scientific American).

Firms have also created their own online communities to foster brainstorming and customer engagement. Dell’s IdeaStorm.com forum collects user feedback and is credited with prompting line offerings, such as the firm’s introduction of a Linux-based laptop.D. Greenfield, “How Companies Are Using I.T. to Spot Innovative Ideas,” InformationWeek, November 8, 2008. At MyStarbucksIdea.com, the coffee giant has leveraged user input to launch a series of innovations ranging from splash sticks that prevent spills in to-go cups, to new menu items. Both IdeaStorm and MyStarbucksIdea run on a platform offered by Salesforce.com’s that not only hosts these sites, but provides integration into Facebook and other services. This platform has allowed Starbucks to leverage Facebook to promote free coffee on election day, a free cup on inauguration day for those pledging five hours of community service, and awareness of the firm’s AIDS-related (RED) campaign. This latter effort garnered an astonishing three hundred ninety million “viral impressions,” including activities such as joining a group to support the cause, messaging others, or making wall posts.M. Brandau, “Starbucks Brews Up Spot on the List of Top Social Brands in 2008,” Nation’s Restaurant News, April 6, 2009.

Concerns

As with any type of social media, content flows in social networks are difficult to control. Embarrassing disclosures can emerge from public systems or insecure internal networks. Employees embracing a culture of digital sharing may err and release confidential or proprietary information. Networks could serve as a focal point for the disgruntled (imagine the activity on a corporate social network after a painful layoff). Publicly declared affiliations, political or religious views, excessive contact, declined participation, and other factors might lead to awkward or strained employee relationships. Users may not want to add a coworker as a friend on a public network if it means they’ll expose their activities, lives, persona, photos, sense of humor, and friends as they exist outside of work. And many firms fear wasted time as employees surf the musings and photos of their peers.

All are advised to be cautious in their social media sharing. Employers are trawling the Internet, mining Facebook, and scouring YouTube for any tip-off that a would-be hire should be passed over. A word to the wise: those Facebook party pics, YouTube videos of open mic performances, or blog postings from a particularly militant period might not age well, and may haunt you forever in a Google search. Think twice before clicking the upload button! As Socialnomics author Erik Qualman puts it, “What happens in Vegas stays on YouTube (and Flickr, Twitter, Facebook…).”

Despite these concerns, trying to micromanage a firm’s social network is probably not the answer. At IBM, rules for online behavior are surprisingly open. The firm’s code of conduct reminds employees to remember privacy, respect, and confidentiality in all electronic communications. Anonymity is not permitted on IBM’s systems, making everyone accountable for their actions. As for external postings, the firm insists that employees don’t disparage competitors or reveal customers’ names without permission, and asks that employee posts from IBM accounts or that mention the firm also include disclosures indicating that opinions and thoughts shared publicly are the individual’s and not Big Blue’s.

Trends to Watch

Global positioning system (GPS)A network of satellites and supporting technologies used to identify a device’s physical location. and location-based services in devices are appearing in social software that allows colleagues and friends to find one another when nearby, ushering in a host of productivity and privacy issues along with them. At the launch of Apple’s iPhone 3G, Loopt CEO Sam Altman showed how the firm’s touch app for iPhones and iPods could display a map with dots representing anyone on his or her contact list who elected to broadcast their whereabouts to him. Claims Altman, “You never have to eat lunch alone again.”

Other efforts seek to increase information exchange and potentially lower switching costs between platforms. Facebook Connect allows users to access affiliated services using their Facebook I.D. and to share information between Facebook and these sites. OpenSocial, sponsored by Google and embraced by MySpace, LinkedIn, and many others, is a platform allowing third-party programmers to build widgets that take advantage of personal data and profile connections across social networking sites. Similarly, DataPortability.org, is an effort, supported by all major public social network platforms, to allow users to migrate data from one site for reuse elsewhere. The initiative should also allow vendors to foster additional innovation and utility through safe, cross-site data exchange.

Key Takeaways

- Electronic social networks help individuals maintain contacts, discover and engage people with common interests, share updates, and organize as groups.

- Modern social networks are major messaging services, supporting private one-to-one notes, public postings, and broadcast updates or “feeds.”

- Social networks also raise some of the strongest privacy concerns, as status updates, past messages, photos, and other content linger, even as a user’s online behavior and network of contacts changes.

- Network effects and cultural differences result in one social network being favored over others in a particular culture or region.

- Information spreads virally via news feeds. Feeds can rapidly mobilize populations, and dramatically spread the adoption of applications. The flow of content in social networks is also difficult to control and sometimes results in embarrassing public disclosures.

- Feeds have a downside and there have been instances where feed mismanagement has caused user discontent, public relations problems, and the possibility of legal action.

- The use of public social networks within private organizations is growing, and many organizations are implementing their own, private, social networks.

- Firms are also setting up social networks for customer engagement and mining these sites for customer ideas, innovation, and feedback.

- Emerging trends related to social networks that bear watching include: the use of e-mail to add contacts; the use of GPS; and the development of platforms to facilitate single sign-on, and sharing of information between sites.

Questions and Exercises

- Visit the major social networks (MySpace, Facebook, LinkedIn). What distinguishes one from the other? Are you a member of any of these services? Why or why not?

- How are organizations like Deloitte, Goldman Sachs, and IBM using social networks? What advantages do they gain from these systems?

- What factors might cause an individual, employee, or firm to be cautious in their use of social networks?

- How do you feel about the feed feature common in social networks like Facebook? What risks does a firm expose itself to if it leverages feeds? How might a firm mitigate these kinds of risks?

- What sorts of restrictions or guidelines should firms place on the use of social networks or the other Web 2.0 tools discussed in this chapter? Are these tools a threat to security? Can they tarnish a firm’s reputation? Can they enhance a firm’s reputation? How so?

- Why do information and applications spread so quickly within networks like Facebook? What feature enables this? What key promotional concept (described in Chapter 2 "Strategy and Technology") does this feature foster?

- Why are some social networks more popular in some nations than others?

- Investigate social networks on your own. Look for examples of their use for fostering political and social movements; for their use in healthcare, among doctors, patients, and physicians; and for their use among other professional groups or enthusiasts. Identify how these networks might be used effectively, and also look for any potential risks or downside. How are these efforts supported? Is there a clear revenue model, and do you find these methods appropriate or potentially controversial? Be prepared to share your findings with your class.

6.5 Twitter and the Rise of Microblogging

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Appreciate the rapid rise of Twitter—its scale, scope, and broad appeal.

- Understand how Twitter is being used by individuals, organizations, and political movements.

- Contrast Twitter and microblogging with Facebook, conventional blogs, and other Web 2.0 efforts.

- Consider the commercial viability of the effort, its competitive environment, and concerns regarding limited revenue.

Spawned in 2006 as a side project at the now-failed podcasting startup Odeo (an effort backed by Blogger.com founder Evan Williams), Twitter had a breakout year in 2009. The actor Ashton Kutcher beat out CNN as owner of the first account to net one million followers. Oprah’s first tweetA Twitter post, limited to 140 characters. is credited with boosting traffic by 43 percent. And by April 2009, Compete.com tracked the site as having thirty-two million visitors, more than the monthly totals for Digg (twenty-three million), the New York Times (seventeen and a half million), or LinkedIn (sixteen million). Reports surfaced of rebuffed buyout offers as high as five hundred million dollars.S. Ante, “Facebook’s Thiel Explains Failed Twitter Takeover,” BusinessWeek, March 1, 2009. Pretty impressive numbers for a firm which that month was reported to have only forty-nine employees.M. Kirkpatrick, “How Twitter’s Staff Uses Twitter (and Why It Could Cause Problems),” ReadWriteWeb, June 5, 2009, http://www.readwriteweb.com/archives/twitters_staff_may_not_use_twitter_like_you_do_tha.php.

Twitter is a microbloggingA type of short-message blogging, often made via mobile device. Microblogs are designed to provide rapid notification to their readership (e.g., a news flash, an update on one’s activities), rather than detailed or in-depth comments. Twitter is the most popular microblogging service. service that allows users to post 140 character tweets via the Web, SMSA text messaging standard used by many mobile phones., or a variety of third-party applications. The microblog moniker is a bit of a misnomer. The service actually has more in common with Facebook’s status update field than traditional blogs. But unlike Facebook, where most users must approve “friends” before they can see status updates, Twitter’s default setting allows for asymmetrical following (although it is possible to set up private Twitter accounts and to block followers).

Sure there’s a lot of inane “tweeting” going on. Lots of meaningless updates that read, “at the coffee shop” or “in line at the airport.” But many find Twitter to be an effective tool for quickly blasting queries to friends, colleagues, or strangers with potentially valuable input. Says futurist Paul Saffo, “Instead of creating the group you want, you send it and the group self-assembles.”C. Miller, “Putting Twitter’s World to Use,” New York Times, April 13, 2009.

Consider the following commercial examples:

- Starbucks uses Twitter in a variety of ways. It has tweeted corrections of bogus claims, such as the rumor the firm was dropping coffee shipments to U.S. troops to protest U.S. war efforts. The firm has also run Twitter-based contests, and promoted free samples of new products, such as its VIA instant coffee line. Starbucks has even recruited and hired off of Twitter.

- Dell got an early warning sign on poor design on its Mini 9 Netbook PC. After a series of early tweets indicated that the apostrophe and return keys were positioned too closely together, the firm dispatched design change orders quickly enough to correct the problem when the Mini 10 was launched just three months later. By June ’09, Dell also claimed to have netted two million dollars in outlet store sales referred via the Twitter account @DellOutlet (more than six hundred thousand followers), and another one million dollars from customers who have bounced from the outlet to the new products site.J. Abel, “Dude—Dell’s Making Money Off Twitter!” Wired News, June 12, 2009.

- The True Massage and Wellness Spa in San Francisco tweets when last-minute cancellations can tell customers of an opening. With Twitter, appointments remain booked solid.

Surgeons and residents at Henry Ford Hospital have even tweeted during brain surgery (the teaching hospital sees the service as an educational tool). Some tweets are from those so young they’ve got “negative age.” Twitter.com/kickbee is an experimental fetal monitor band that sends tweets when motion is detected: “I kicked Mommy at 08:52.” And savvy hackers are embedding “tweeting” sensors into all sorts of devices. Botanicalls (http://www.botanicalls.com), for example, offers a sort of electronic flowerpot stick that detects when plants need water and sends Twitter status updates to a mobile phone.

Twitter has provided early warning on earthquakes, terror attacks, and other major news events. And the site was seen as such a powerful force that the Iranian government blocked access to Twitter (and other social media sites) in an attempt to quell the June 2009 election protests. Users quickly assemble comments on a given topic using hash tagsA method for organizing tweets where keywords are preceeded by the # character. (keywords proceeded by the # or “hash” symbol), allowing others to quickly find related tweets (e.g., #iranelection, #mumbai, #swineflu, #sxsw).

Organizations are well advised to monitor Twitter activity related to the firm, as it can act as a sort of canary-in-a-coal mine uncovering emerging events. Users are increasingly using the service as a way to form flash protest crowds. Amazon.com, for example, was caught off guard over a spring 2009 holiday weekend when thousands used Twitter to rapidly protest the firm’s reclassification of gay and lesbian books (hash tag #amazonfail).

For all the excitement, many wonder if Twitter is overhyped. All the adoption success mentioned above came to a firm with exactly zero dollars in revenue—none! Many wonder how the site will make money, if revenues will ever justify initially high valuations, and if rivals could usurp Twitter’s efforts with similar features. Another issue—many loyal Twitter users rarely visit the site. Most active users post and read tweets using one of the dozens of free applications provided by third parties, such as Seesmic, TweetDeck, Tweetie, and Twirl. If users don’t visit Twitter.com, that lessens the impact of any ads running on the site (although Twitter was not running any ads on its site as of this writing). This creates what is known as the “free rider problemWhen others take advantage of a user or service without providing any sort of reciprocal benefit.,” where users benefit from a service while offering no value in exchange. And some reports suggest that many Twitter users are curious experimenters who drop the service shortly after signing up.D. Martin, “Update: Return of the Twitter Quitters,” Nielsen Wire, April 30, 2009.

Microblogging is here to stay and the impact of Twitter has been deep, broad, stunningly swift, and at times humbling in the power it provides. But whether or not Twitter will be a durable, profit-gushing powerhouse remains to be seen.

Key Takeaways

- While many public and private microblogging services exist, Twitter remains by far the dominant service.

- Unlike status updates found on services like Facebook and LinkedIn, Twitter’s default supports asymmetric communication, where someone can follow updates without first getting their approval. This function makes Twitter a good choice for anyone cultivating a following—authors, celebrities, organizations, and brand promoters.

- Twitter hash tags (keywords proceeded by the # character) are used to organize “tweets” on a given topic. Users can search on hash tags, and many third-party applications allow for Tweets to be organized and displayed by tag.

- Firms are leveraging Twitter in a variety of ways, including: promotion, customer response, gathering feedback, and time-sensitive communication.

- Like other forms of social media, Twitter can serve as a hothouse that attracts opinion and forces organizational transparency and accountability.

- Activists have leveraged the service worldwide, and it has also served as an early warning mechanism in disasters, terror, and other events.

- Despite its rapid growth and impact, significant questions remain regarding the firm’s durability, revenue prospects, and enduring appeal to initial users.

Questions and Exercises

- If you don’t already have one, set up a Twitter account and “follow” several others. Follow a diverse group—corporations, executives, pundits, or other organizations. Do you trust these account holders are who they say they are? Why? Which examples do you think use the service most effectively? Which provide the weaker examples of effective Twitter use? Why? Have you encountered Twitter “spam” or unwanted followers? What can you do to limit such experiences? Be prepared to discuss your experiences with class.

- If you haven’t done so, install a popular Twitter application such as TweetDeck, Seesmic, or a Twitter client for your mobile device. Why did you select the product you chose? What advantages does your choice offer over simply using Twitter’s Web page? What challenges do these clients offer Twitter? Does the client you chose have a clear revenue model? Is it backed by a viable business?

- Which Twitter hash tags are most active at this time? What do you think of the activity in these areas? Is there legitimate, productive activity happening?

- Why would someone choose to use Twitter over Facebook’s status update, or other services? Which (if either) do you prefer and why?

- What do you think of Twitter’s revenue prospects? Is the firm a viable independent service or simply a feature to be incorporated into other social media activity? Advocate where you think the service will be in two years, five, ten. Would you invest in Twitter? Would you suggest that other firms do so? Why?

- Assume the role of a manager for your firm. Advocate how the organization should leverage Twitter and other forms of social media. Provide examples of effective use, and cautionary tales, to back up your recommendation.

- Some instructors have mandated Twitter for classroom use. Do you think this is productive? Would your professor advocate tweeting during lectures? What are the pros and cons of such use? Work with your instructor to discuss a set of common guidelines for in-class and course use of social media.

6.6 Other Key Web 2.0 Terms and Concepts

Learning Objectives

After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

- Know key terms related to social media, peer production, and Web 2.0, including RSS, folksonomies, mash-ups, virtual worlds, and rich media.

- Be able to provide examples of the effective business use of these terms and technologies.

RSS

RSSA method for sending/broadcasting data to users who subscribe to a service’s “RSS feed.” Many Web sites and blogs forward headlines to users who subscribe to their “feed,” making it easy to scan headlines and click to access relevant news and information. (an acronym that stands for both “really simple syndication” and “rich site summary”) enables busy users to scan the headlines of newly available content and click on an item’s title to view items of interest, thus sparing them from having to continually visit sites to find out what’s new. Users begin by subscribing to an RSS feed for a Web site, blog, podcast, or other data source. The title or headline of any new content will then show up in an RSS readerA tool for subscribing to and accessing RSS feeds. Most e-mail programs and Web browsers can also act as RSS readers. There are also many Web sites (including Google Reader) that allow users to subscribe to and read RSS feeds.. Subscribe to the New York Times Technology news feed, for example, and you will regularly receive headlines of tech news from the Times. Viewing an article of interest is as easy as clicking the title you like. Subscribing is often as easy as clicking on the RSS icon appearing on the home page of a Web site of interest.

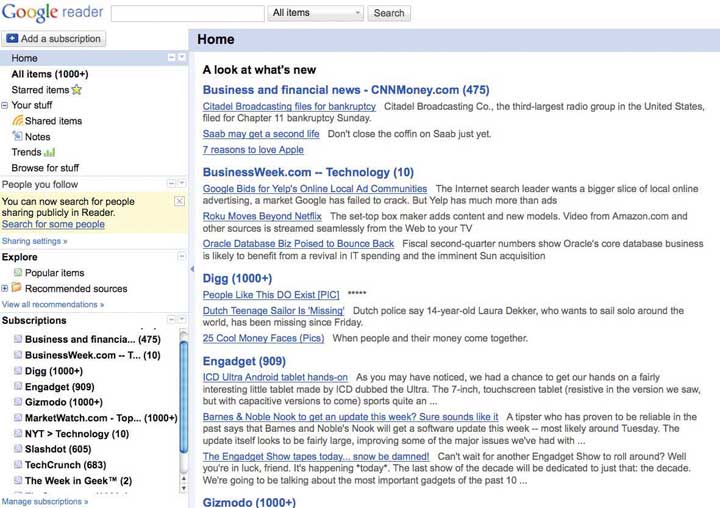

Figure 6.1

RSS readers like Google Reader can be an easy way to scan blog headlines and click through to follow interesting stories.

Figure 6.2

Web sites that support RSS feeds will have an icon in the address bar. Click it to subscribe.

Many firms use RSS feeds as a way to mange information overload, opting to distribute content via feed rather than e-mail. Some even distribute corporate reports via RSS. RSS readers are offered by third-party Web sites such as Google and Yahoo! and they have been incorporated into all popular browsers and most e-mail programs. Most blogging platforms provide a mechanism for bloggers to automatically publish a feed when each new post becomes available. Google’s FeedBurner is the largest publisher of RSS blog feeds, and offers features to distribute content via e-mail as well.

Folksonomies

FolksonomiesKeyword-based classification systems created by user communities. (sometimes referred to as social tagging) are keyword-based classification systems created by user communities as they generate and review content. (The label is a combination of “folks” and “sonomy,” meaning a people-powered taxonomy). Bookmarking site Del.icio.us and photo-sharing site Flickr (both owned by Yahoo!) make heavy use of folksonomies.

With this approach, classification schemes emerge from the people most likely to understand them—the users. By leveraging the collective power of the community to identify and classify content, objects on the Internet become easier to locate, and content carries a degree of recommendation and endorsement.

Flickr cofounder Stewart Butterfield describes the spirit of folksonomies, saying, “The job of tags isn’t to organize all the world’s information into tidy categories, it’s to add value to the giant piles of data that are already out there.”Daniel Terdiman, “Folksonomies Tap People Power,” Wired, February 1, 2005. The Guggenheim Museum in New York City and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among other museums, are taking a folksonomic approach to their online collections, allowing user-generated categories to supplement the specialized lexicon of curators. Amazon.com has introduced a system that allows readers to classify books, and most blog posts and wiki pages allow for social tagging, oftentimes with hot topics indexed and accessible via a “tag cloud” in the page’s sidebar.

Mash-up

Mash-upsThe combination of two or more technologies or data feeds into a single, integrated tool. are combinations of two or more technologies or data feeds into a single, integrated tool. Some of the best known mash-ups leverage Google’s mapping tools. HousingMaps.com combines Craigslist.org listings with Google Maps for a map-based display for apartment hunters. IBM linked together job feeds and Google Maps to create a job-seeker service for victims of Hurricane Katrina. SimplyHired links job listings with Google Maps, LinkedIn listings, and salary data from PayScale.com. And Salesforce.com has tools that allow data from its customer relationship management (CRM) system to be combined with data feeds and maps from third parties.

Mash-ups are made easy by a tagging system called XMLAbbreviation of Extensible Markup Language. A tagging language that can be used to identify data fields made available for use by other applications. For example, programmers may wrap XML tags around elements in an address data stream (e.g., <business name>, <street address>, <city>, <state>) to allow other programs to recognize and use these data items. (for extensible markup language). Site owners publish the parameters of XML data feeds that a service can accept or offer (e.g., an address, price, product descriptions, images). Other developers are free to leverage these public feeds using application programming interfaces (APIs)Programming hooks, or guidelines, published by firms that tell other programs how to get a service to perform a task such as send or receive data. For example, Amazon.com provides APIs to let developers write their own applications and Websites that can send the firm orders., published instructions on how to make programs call one another, to share data, or to perform tasks. Using APIs and XML, mash-up authors smoosh together seemingly unrelated data sources and services in new and novel ways. Lightweight, browser-friendly software technologies like Ajax can often make a Web site interface as rich as a desktop application, and rapid deployment frameworks like Ruby on Rails will enable and accelerate mash-up creation and deployment.

Virtual Worlds

In virtual worldsA computer-generated environment where users present themselves in the form of an avatar, or animated character., users appear in a computer-generated environment in the form of an avatarAn online identity expressed by an animated or cartoon figure., or animated character. Users can customize the look of their avatar, interact with others by typing or voice chat, and can travel about the virtual world by flying, teleporting, or more conventional means.

The most popular general-purpose virtual world is Second Life by Linden Labs, although many others exist. Most are free, although game-oriented worlds, such as World of Warcarft (with ten million active subscribers) charge a fee. Many corporations and organizations have established virtual outposts by purchasing “land” in the world of Second Life, while still others have contracted with networks to create their own, independent virtual worlds.

Even grade schoolers are heavy virtual world users. Many elementary school students get their first taste of the Web through Webkinz, an online world that allows for an animated accompaniment with each of the firm’s plush toys. Webkinz’s parent, privately held Ganz doesn’t release financial figures, but according to Compete.com, by year-end 2008 Webkinz.com had roughly the same number of unique visitors as FoxNews. The kiddie set virtual world market is considered so lucrative that Disney acquired ClubPenguin for three hundred fifty million dollars with agreements to pay another potential three hundred fifty million if the effort hits growth incentives.B. Barnes, “Disney Acquires Web Site for Children,” New York Times, August 2. 2007.

Most organizations have struggled to commercialize these Second Life forays, but activity has been wide-ranging in its experimentation. Reuters temporarily “stationed” a reporter in Second Life, presidential candidates have made appearances in the virtual world, organizations ranging from Sun Microsystems to Armani have set up virtual storefronts, and there’s a significant amount of virtual mayhem. Second Life “terrorists” have “bombed” virtual outposts run by several organizations, including ABC News, American Apparel, and Reebok.

YouTube, Podcasting, and Rich Media

Blogs, wikis, and social networks not only enable sharing text and photos, they also allow for the creation and distribution of audio and video. PodcastsDigital audio or video files served as a series of programs or a multimedia blog. are digital audio files (some also incorporate video), provided as a series of programs. Podcasts range from a sort of media blog, archives of traditional radio and television programs, and regular offerings of original online content. While the term podcast derives from Apple’s wildly successful iPod, podcasts can be recorded in audio formats such as MP3 that can be played on most portable media players. (In perhaps the ultimate concession to the market leader, even the iPod rival Microsoft Zune refers to serialized audio files as podcasts on its navigation menu).

There are many podcast directories, but Apple’s iTunes is by far the largest. Anyone who wants to make a podcast available on iTunes can do so for free. A podcast publisher simply records an audio file, uploads the file to a blog or other hosting server, then sends the RSS feed to Apple (copyrighted material cannot be used without permission, with violators risking banishment from iTunes). Files are discovered in the search feature of the iTunes music store, and listings seamlessly connect the user with the server hosting the podcast. This path creates the illusion that Apple serves the file even though it resides on a publisher’s servers.