This is “Market Failures and Public Choice”, section 11.1 from the book Finance, Banking, and Money (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

11.1 Market Failures and Public Choice

Learning Objective

- Why can’t the government legislate bad things out of existence and which model of government, public interest or private interest, is the most accurate depiction of reality?

Some regulations are clearly salubrious and should be retained. The main justifications for financial system regulation—market failuresThe inefficient allocation of resources by a free market caused by asymmetric information, externalities (costs or benefits not reflected in market prices), natural monopolies or other forms of excessive market power, and public goods (goods like national defense that cannot be profitably supplied by non-government entities due to free-rider problems).—do occur, and government regulations can, and sometimes have, helped to mitigate them. Like everything else in life, however, regulations are costly (not gratis) and hence entail trade-offs. As detailed in another chapter, they induce perfectly legal but bureaucratically disruptive loophole miningThe search for ways around regulations. and lobbyingAttempts to change regulations. activities. They can also lead to severely twisted, unintended consequencesEvents (usually negative) caused by regulations that lawmakers did not foresee., like banks purposely making bad loans.

The goal of this chapter is not to bash all regulation but rather to critique specific financial regulations in the hopes of creating better regulatory policies in the (hopefully near) future. The place to start, I believe, is to think about what regulators and regulations cannot do, and that is fix the world by decree. Simply making an activity illegal does not mean that it will stop. Because the government faces a budget constraint and opportunity costs, it can’t afford to monitor everyone all the time. What’s bad for some is often good for others, so many people willingly supply illegal goods or activities. As a result, many illegal activities are commonplace; in no particular order, sodomy, drug use, reckless use of automobiles, and music piracy come to mind. This may seem like a simple point, but many people believe that regulation can really work if only regulations, and the regulators charged with enforcing them, are strengthened. If regulations failed in the past, they believe that means regulators needed more money or authority, or both.

The problem with this view, however, is that government officials may not be the angels many people assume they are. It’s not their fault. Especially if they went through the U.S. public school system, they likely learned an interpretation of government called the public interest model. As its name suggests, the public interest modelA model of government developed by political scientists that posits that politicians, bureaucrats, and other government workers serve the public in lieu of themselves. posits that government officials work in the interests of the public, of “the people,” if you will. It’s the sort of thing Abraham Lincoln had in mind in his famous Gettysburg Address when he said “that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”showcase.netins.net/web/creative/lincoln/speeches/gettysburg.htm That’s outstanding political rhetoric, better than anything current spin artists concoct, but is it a fair representation of reality?

Many economists think not. They believe that private interest prevails, even in the government. According to their model, called the public choiceSee private interest model. or, less confusingly, the private interest modelA model of government developed by economists that posits that politicians, bureaucrats, and other government workers serve themselves in lieu of the citizens or public., politicians and bureaucrats often behave in their own interests rather than those of the public. Of course, they don’t go around saying that we need law X or regulation Y to help me to get rich via bribes, to bailout my brother-in-law, or to ensure that I soon receive a cushy job in the private sector. Rather, they say that we need law X or regulation Y to protect widows and orphans, to stymie the efforts of bad guys, or to make the rich pay for their success.

In many countries, the ones we will call “predatory” in the context of the Growth Diamond model, the private interest model clearly holds sway. In rich countries, the public interest model becomes more plausible. Nevertheless, many economic regulations, though clothed in public interest rhetoric, appear on close inspection to conform to the private interest model. As University of Chicago economist and Nobel Laureate George Stiglerwww.econlib.org/LIBRARY/Enc/bios/Stigler.html pointed out decades ago, regulators are often “captured”en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regulatory_capture by the industry they regulate. In other words, the industry establishes regulations for itself by influencing the decisions of regulators. Financial regulators, as we’ll see, are no exception.

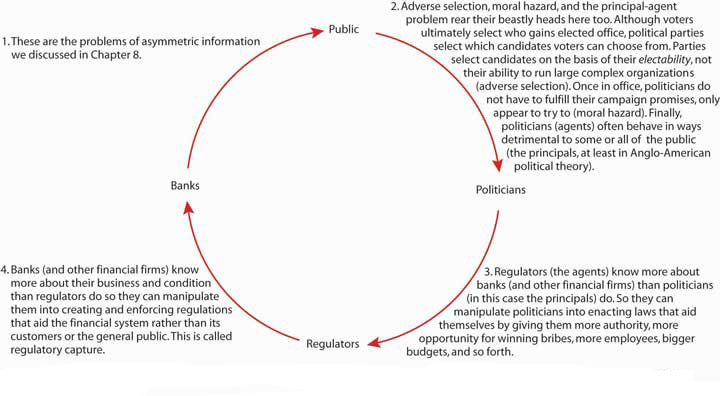

Regardless of regulators’ and politicians’ motivations, another very sticky question arises: could regulators stop bad activities, events, and people even if they wanted to? The answer in many contexts appears to be an unequivocal “No!” The reason is our old nemesis, asymmetric information, which, readers should recall, inheres in nature and pervades all. It flummoxes governments as much as markets and intermediaries. The implications of this insight are devastating for the effectiveness of regulators and their regulations, as Figure 11.1 "Asymmetric information and regulation" makes clear.

Figure 11.1 Asymmetric information and regulation

Source: Adapted from James R. Barth, Gerard Caprio Jr., and Ross Levine, Rethinking Bank Regulation: Til Angels Govern (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 6.

Although Figure 11.1 "Asymmetric information and regulation" is esthetically pleasing (great job, guys!) it does not paint a pretty picture. Due to multiple levels of nearly intractable problems of asymmetric information, democracyA type of government that is of, for, and by the people because it allows citizens to choose candidates and policies via elections. is no guarantee that government will serve the public interest. Matters are even worse in societies still plagued by predatory governmentA type of government that is of, for, and by the ruling elite and that fails to supply basic public goods like life, liberty, and property., where corruption further fouls up the works by giving politicians, regulators, and bankers (and other financiers) incentives to perpetuate the current system, no matter how suboptimal it may be from the public’s point of view.

And if you really want to get your head spinning, consider this: agency problems within the government, within regulatory bureaucracies, and within banks abound. Within banks, traders and loan officers want to keep their jobs, earn promotions, and bring home large bonuses. They can do the latter two by taking large risks, and sometimes they choose to do so. Sometimes shareholders want to take on much larger risks than managers or depositors or other debt holders do. Sometimes it’s the managers who have incentives to place big bets, to get their stock options “in the money.”www.investorwords.com/2580/in_the_money.html Within bureaucracies, regulators have incentives to hide their mistakes and to take credit for good outcomes, even if they had little or nothing to do with them. The same is true for the government, where the legislature may try to discredit the executive’s policies, or vice versa, and withhold information or even spread disinformation to “prove” its case.

Stop and Think Box

In the 1910s and early 1920s, a majority of U.S. states passed securities regulations called Blue Sky Laws that ostensibly sought to prevent slimy securities dealers from selling nothing but the blue sky to poor, defenseless widows and orphans. Can you figure out what was really going on? (Hint: Recall that this was a period of traditional banking, unit banks, the 3-6-3 rule, and all that. Recall, too, that securities markets are an alternative method of linking investors to borrowers.)

We probably gave it away with that last hint. Blue Sky Laws, scholars now realize, were veiled attempts to protect the monopolies of unit bankers upset about losing business to the securities markets. Unable to garner public sympathy for their plight, the bankers instead spoke in terms of public interest, of defrauded widows and orphans. There were certainly some scams about, but not enough to warrant the more virulent Blue Sky Laws, which actually gave state officials the power to forbid issuance of securities they didn’t like, and in some states, that was most of them!

It’s okay if you feel a bit uneasy with these new ideas. I think that as adults you can handle straight talk. It’ll be better for everyone—you, me, our children and grandchildren—if you learn to look at the government’s actions with a critical eye. Regulators have failed in the past and will do so again unless we align the interests of all the major parties depicted in Figure 11.1 "Asymmetric information and regulation" more closely, empowering market forces to do most of the heavy lifting.

Key Takeaways

- The government can’t legislate bad things away because it can’t be every place at once. Like the rest of us, government faces budget constraints and opportunity costs. Therefore, it cannot stop activities that some people enjoy or find profitable.

- According to the public interest model, government tries to enact laws, regulations, and policies that benefit the public.

- The private interest (or public choice) model, by contrast, suggests that government officials enact laws that are in their own private interest.

- It is important to know which model is a more accurate description of reality because the models have very different implications for our attitudes toward regulation.

- If one believes the public interest model is usually correct, then one will be more likely to call for government regulation, even if one admits that regulatory goals may in fact be difficult to achieve regardless of the intentions of politicians and bureaucrats.

- If one believes the private interest model is a more accurate depiction of the real world, one will be more skeptical of government regulation.

- Asymmetric information creates a principal-agent problem between the public and elected officials, another principal-agent problem between those officials and regulators, and yet another principal-agent problem between regulators and banks (and other financial firms) because in each case, one party (politicians, regulators, banks) knows more than the other (public, politicians, regulators).

- So there are at least three places where the public’s interest can be stymied: in political elections, in the interaction between Congress and the president and regulatory agencies, and in the interaction between regulators and the regulated. And that’s ignoring the often extensive agency problems found within governments, regulatory agencies, and financial institutions!