This is “Banking Industry Profitability and Structure”, section 10.5 from the book Finance, Banking, and Money (v. 1.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

10.5 Banking Industry Profitability and Structure

Learning Objective

- What role does market structure (concentration, consolidation, conglomeration) play in the banking industry’s profitability?

Despite their best innovation efforts, banks have been steadily losing market share as sources of loans to nonfinancial borrowers. In the 1970s, commercial banks and other depository institutions (the so-called thrifts—credit unions, savings and loans, savings banks) controlled over 60 percent of that market. Today, they have only about a third. The market for loans to nonfinancial borrowers grew very quickly over the last quarter century, however, so that decline is a relative one only. Banks are still extremely profitable, so much so that many new banks form each year. But bankers have to work harder than ever for those profits; the good old days of traditional banking and the 3-6-3 rule are long gone. Fees and other off-balance-sheet activities now account for almost half of bank income, up from about 7 percent in 1980. The traditional source of profit, the spread between the cost of liabilities and the returns on assets, has steadily eroded from both ends.

As noted above, the interest rates that banks could pay on deposits were capped (under so-called Regulation Q) at 0 for checking deposits and about 6 percent on time deposits. Until the Great Inflation, bankers loved the caps because they limited competition for deposits. When interest rates rose enough to cause disintermediation, to cause funds to flow out of banks to higher-yielding investments like money market mutual funds, bankers lobbied for an end to the interest rate restrictions and their request was granted in the 1980s. Since then, banks have had to compete with each other as well as with money market mutual funds for deposits. Unsurprisingly, banks have to pay more for deposits than ever before (the general level of interest rates constant). Little wonder that deposits have become relatively less important as sources of funds for banks.

On the asset side, banks can’t charge as much for loans, ceteris paribus, as they once did because they face increasingly stiff competition from the commercial paper and bond markets, especially the so-called junk bond market. Now, instead of having to cozy up to a bank, smaller and riskier companies can sell bonds directly to investors. Issuing bonds incurs costs besides interest charges—namely, mandatory information disclosure and constant feedback from investors on the issuing firm’s performance via its bond prices—but companies are willing to bear those costs if they can get a better interest rate than banks offer.

As mentioned above, securitization has also hurt banks by giving rise to numerous small lenders that basically sell every loan they originate. Such companies can be efficient at smaller scale because they do not have to attract and retain deposits or engage in more sophisticated asset and liability management techniques. All they have to do is originate loans and sell them to investors, using the proceeds to make new loans. Finance companies especially have eaten into banks’ market share in commercial lending, and a slew of specialized mortgage lenders made major inroads into the home mortgage market. What is good for the goose, as they say, is good for the gander.http://www.bartleby.com/59/3/whatsgoodfor.html

As a result of those competitive pressures, many banks exited the business, some by going bankrupt, others by merging with larger institutions. The banking crisis of the 1980s enabled bankers and regulators to make further reforms, including greatly easing restrictions on branch banking and investment banking (securities) activities. In 1933, at the nadir of the Great Depression, commercial and investment banking activities, receiving deposits and making loans and underwriting securities offerings, respectively, were strictly separated by legislation usually called Glass-Steagall, after the congressional members who cooked it up. The gradual de facto erosion of Glass-Steagall in the late 1980s and 1990s (by means of bank holding companies and a sympathetic Federal Reserve) and its de jure elimination in 1999 allowed investment and commercial banks to merge and to engage in each other’s activities. Due to those and other regulatory changes, usually called deregulation, and the decline of traditional banking, banks began to merge in large numbers, a process called consolidation, and began to enter into nonbanking financial activities, like insurance, a process called conglomeration.

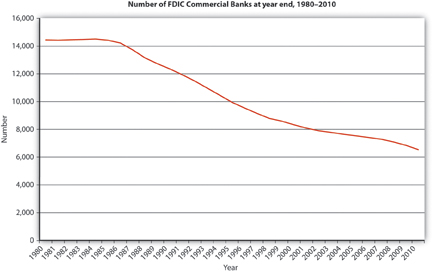

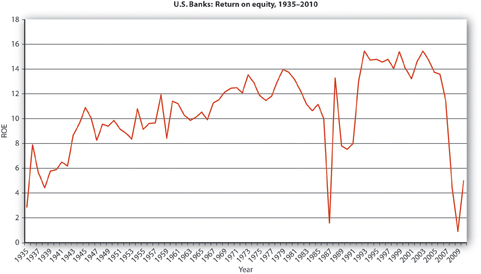

As Figure 10.4 "Number of FDIC commercial banks, year-end, 1980–2010" and Figure 10.5 "U.S. banks: return on equity, 1935–2010" show, consolidation and conglomeration have left the nation with fewer but larger and more profitable (and ostensibly more efficient) banks. Due to the demise of Glass-Steagall, conglomerate banks can now more easily tap economies of scope, the ability to use a single resource to supply numerous products or services. For example, banks can now use the information they create about borrowers to offer loans or securities underwriting and can use branches to schlep insurance. Consolidation has also allowed banks to diversify their risks geographically and to tap economies of scale. That is important because minimum efficient scale may have increased in recent decades due to the high initial costs of employing the latest and greatest computer and telecommunications technologies.

Figure 10.4 Number of FDIC commercial banks, year-end, 1980–2010

Figure 10.5 U.S. banks: return on equity, 1935–2010

The Federal Reserve labels the entities that have arisen from the recent wave of mergers large, complex banking organizations (LCBOs) or large, complex financial institutions (LCFIs). Those names, though, also point to the costs of the new regime. Consolidation may have made banks and other financial institutions too big, complex, and politically potent to regulate effectively. Also, to justify their merger activities to shareholders, many banks have increased their profitability, not by becoming more efficient, but by taking on higher levels of risk. Finally, conglomerates may be able to engage in many different activities, thereby diversifying their revenues and risks, but they may not do any of them very well, thereby actually increasing the risk of failure. As we’ll see in Chapter 11 "The Economics of Financial Regulation" and Chapter 12 "The Financial Crisis of 2007–2009", a combination of consolidation, conglomeration, and concentration helped to trigger a systemic financial crisis acute enough to negatively affect the national and world economies.

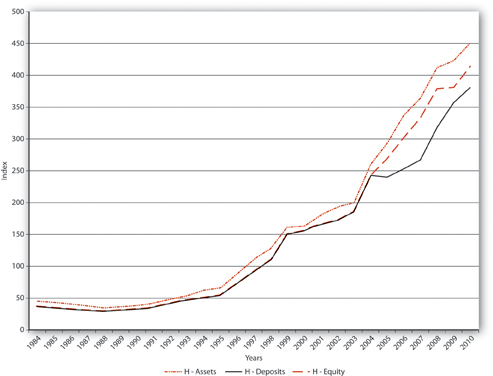

Today, the U.S. banking industry is far more concentrated than during most of its past. In other words, a few large banks have a larger share of assets, deposits, and capital than ever before. That may in turn give those banks considerable market power, the ability to charge more for loans and to pay less for deposits. Figure 10.6 "Concentration in the U.S. banking sector, 1984–2010" shows the increase in the industry’s Herfindahl indexA measure of market concentration calculated by summing the square of the market shares of the companies operating in a given market., which is a measure of market concentration calculated by taking the sum of the squares of the market shares of each firm in a particular industry. Whether scaled between 0 and 1 or 0 and 10,000, the Herfindahl index is low (near zero) if an industry is composed of numerous small firms, and it is high (near 1 or 10,000) the closer an industry is to monopoly (1 × 1 = 1; 100 × 100 = 10,000). While the Herfindahl index of the U.S. banking sector has increased markedly in recent years, thousands of small banks keep the national index from reaching 1,800, the magic number that triggers greater antitrust scrutiny by the Justice Department. At the end of 2006, for example, 3,246 of the nation’s 7,402 commercial banks had assets of less than $100 million. Another 3,662 banks had assets greater than $100 million but less than $1 billion, leaving only 494 banks with assets over $1 billion.

Figure 10.6 Concentration in the U.S. banking sector, 1984–2010

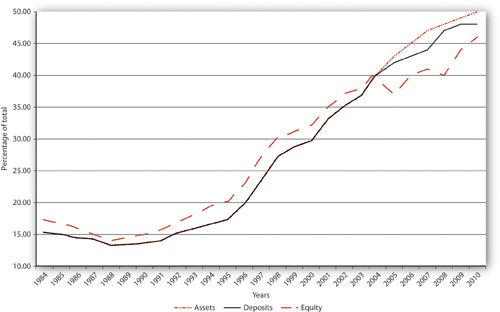

Figure 10.7 Shares of top ten U.S. banks, 1984–2010

Those 500 or so big banks, however, control the vast bulk of the industry’s assets (and hence liabilities and capital too). As Figure 10.7 "Shares of top ten U.S. banks, 1984–2010" shows, the nation’s ten largest banks are rapidly gaining market share. Nevertheless, U.S. banking is still far less concentrated than the banking sectors of most other countries. In Canada, for example, the commercial bank Herfindahl index hovers around 1,600, and in Colombia and Chile, the biggest five banks make more than 60 percent of all loans. The United States is such a large country and banking, despite the changes wrought by the Information Revolution, is still such a local business that certain regions have levels of concentration high enough that some fear that banks there are earning quasi-monopoly rents, the high profits associated with oligopolistic and monopolistic market structures. The good news is that bank entry is fairly easy, so if banks become too profitable in some regions, new banks will form to compete with them, bringing the Herfindahl index, n-firm concentration ratios, and ultimately bank profits back in line. Since the mid-1980s, scores to hundreds of new banks, called de novo banks, began operation in the United States each year.

Stop and Think Box

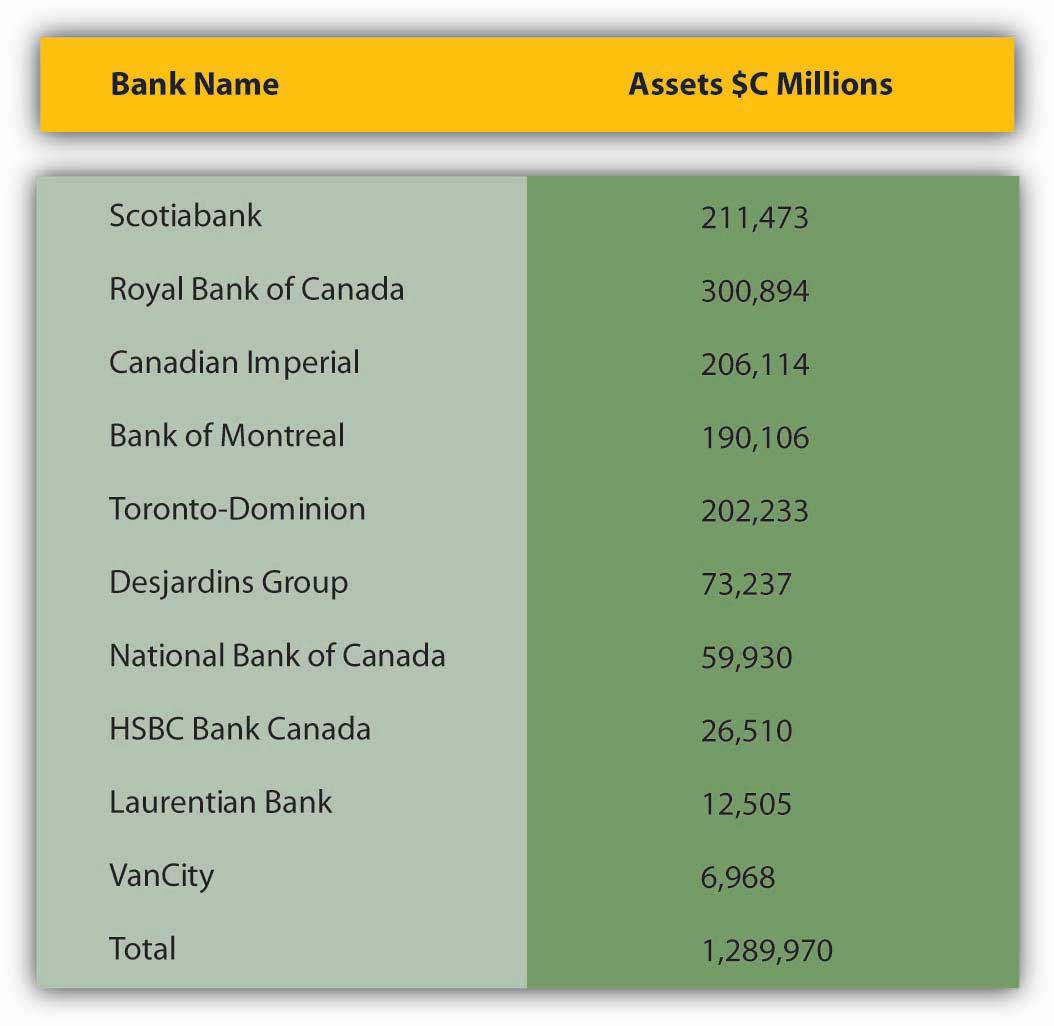

In 2003, Canada was home to the banks listed in Figure 10.8 "Canadian bank assets, 2003". How concentrated was the Canadian banking sector as measured by the five-firm concentration ratio? The Herfindahl index?

Figure 10.8 Canadian bank assets, 2003

The five-firm concentration ratio is calculated simply by summing the market shares of the five largest banks, as shown in Figure 10.9 "Five-firm concentration ratio":

Figure 10.9 Five-firm concentration ratio

So the five-bank concentration ratio (for assets) in Canada in 2003 was 86 percent.

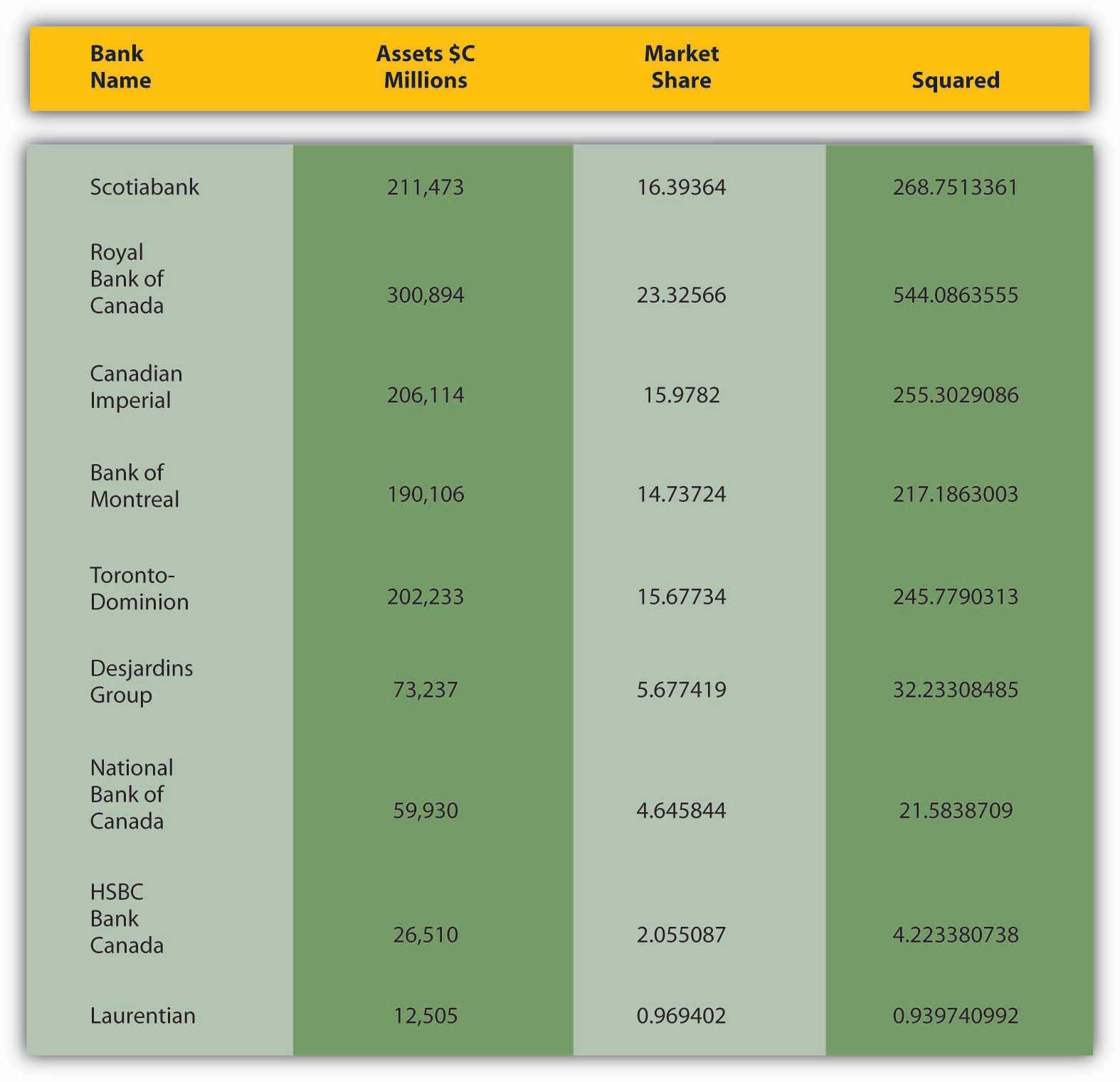

The Herfindahl index is calculated by summing the squares of the market shares of each bank, as shown in Figure 10.10 "Herfindahl index":

Figure 10.10 Herfindahl index

So the Herfindahl index for bank assets in Canada in 2003 was 1,590.

Starting a new bank is not as difficult as it sounds. About twenty or so incorporators need to put about $50,000 each at risk for the year or two it takes to gain regulatory approval. They must then subscribe at least the same amount in a private placement of stock that provides the bank with some of its capital. The new bank can then begin operations, usually with two branches, one in an asset-rich area, the other in a deposit-rich one. Consultants like Dan Hudson of NuBank.com help new banks to form and begin operations.http://www.nubank.com/ Due to the ease of creating new banks and regulations that effectively cap the size of megabanks, the handful of U.S. banks with over $1 trillion of assets, many observers think that the U.S. banking sector will remain competitive, composed of numerous small banks, a few (dozen, even score) megabanks, and hundreds of large regional players. The small and regional banks will survive by exploiting geographical and specialized niches, like catering to depositors who enjoy interacting with live people instead of machines. Small banks also tend to lend to small businesses, of which America has many. Despite funny television commercials to the contrary, large banks will also lend to small businesses, but smaller, community banks are often better at it because they know more about local markets and borrowers and hence can better assess their business plans.http://www.icba.org/communitybanking/index.cfm?ItemNumber=556&sn.ItemNumber=1744

The United States also allows individuals to establish other types of depository institutions, including savings and loan associations, mutual savings banks, and credit unions. Few new savings banks are created, and many existing ones have taken commercial bank charters or merged with commercial banks, but new credit union formation is fairly brisk. Credit unions are mutual (that is, owned by depositors rather than shareholders) depository institutions organized around a group of people who share a common bond, like the same employer. They are tax-exempt and historically quite small. Recently, regulators have allowed them to expand so that they can maintain minimum efficient scale and diversify their asset portfolios more widely.

The U.S. banking industry is also increasingly international in scope. Thus, foreign banks can enter the U.S. market relatively easily. Today, foreign banks hold more than 10 percent of total U.S. bank assets and make more than 16 percent of loans to U.S. corporations. Foreign banks can buy U.S. banks or they can simply establish branches in the United States. Foreign banks used to be subject to less stringent regulations than domestic banks, but that was changed in 1978. Increasingly, bank regulations worldwide have converged, a point we’ll take up again in Chapter 11 "The Economics of Financial Regulation".

The internationalization of banking also means that U.S. banks can operate in other countries. To date, about 100 U.S. banks have branches abroad, up from just eight in 1960. International banking has grown along with international trade and foreign direct investment. International banking is also a way to diversify assets, tap markets where spreads are larger than in the United States, and get a piece of the Eurodollar market. Eurodollars are dollar-denominated deposits in foreign banks that help international businesses to conduct trade and banks to avoid reserve requirements and other taxing regulations and capital controls. London, Singapore, and the Cayman Islands are the main centers for Eurodollars and, not surprisingly, favorite locations for U.S. banks to establish overseas branches. To help finance trade, U.S. banks also have a strong presence elsewhere, particularly in East Asia and in Latin America.

The nature of banking in the United States and abroad is changing, apparently converging on the European, specifically the British, model. In some countries in continental Europe, like Germany and Switzerland, so-called universal banks that offer commercial and investment banking services and insurance prevail. In other countries, like Great Britain and its commonwealth members, full-blown financial conglomerates are less common, but most banks engage in both commercial and investment banking activities. Meanwhile, foreign securities markets are modeling themselves after American markets, growing larger and more sophisticated. Increasingly, the world’s financial system is becoming one. That should make it more efficient, but it also raises fears of financial catastrophe, a point to which we shall return.

Key Takeaways

- Industry consolidation is measured by the number of banks in existence at a given time.

- As the number of banks declines (because mergers and bankruptcies exceed new bank formation), the industry is said to become more consolidated. It is important because a more consolidated industry may be safer and more profitable as smaller, weaker institutions are swallowed up by larger, stronger ones.

- However, consolidation can also lead to higher costs for consumers and borrowers and poorer service.

- Bigger banks are likely to be more diversified than smaller ones, but they might also take on higher levels of risk, thereby threatening the stability of the financial system.

- Conglomeration refers to the scope of activities that a bank or other financial intermediary is allowed to engage in.

- Traditionally, U.S. banks could engage in commercial banking activities or investment banking activities, but not both, and they could not sell or underwrite insurance. Due to recent regulatory changes, however, banks and other financial intermediaries and facilitators like brokerages can now merge into the same company or exist under the same holding company umbrella.

- This deregulation may increase competition for financial intermediaries, thereby driving innovation. It could also lead, however, to the creation of financial conglomerates that are too large and complex to regulate adequately.

- Industry concentration is a proxy for competition and is measured by the n-firm concentration of assets (revenues, capital, etc., where n is 1, 3, 5, 10, 25, 50, etc.) or by the Herfindahl index, the sum of the square of the market shares (again for assets, deposits, revenues, capital, etc.) of each company in the industry or in a given city, state, or region.

- Concentration is important because a highly concentrated industry may be less competitive, leading to less innovation, higher costs for borrowers, outsized profits for suppliers (in this case banks), and a more fragile (prone to systemic crisis) banking system.

- On the other hand, as banking has grown more concentrated, individual banks have become more geographically diversified, which may help them to better weather economic downturns.