This is “Financial Intermediaries”, section 2.5 from the book Finance, Banking, and Money (v. 1.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

2.5 Financial Intermediaries

Learning Objective

- In what ways can financial intermediaries be classified?

Like financial markets, financial intermediaries are highly specialized. Sometimes called the indirect method of finance, intermediaries, like markets, link investors/lenders/savers to borrowers/entrepreneurs/spenders but do so in an ingenious way, by transforming assetsAssets are “things owned” as opposed to liabilities, which are “things owed.”. Unlike facilitators, which, as we have seen, merely broker or buy and sell the same securities, intermediaries buy and sell instruments with different riskThe probability of loss., returnThe percentage gain or loss from an investment., and/or liquidity characteristics. The easiest example to understand is that of a bank that sells relatively low risk (which is to say, safe), low return, and highly liquid liabilitiesLiabilities are “things owed” to others, as opposed to assets, which are “things owned.”, called demand deposits, to investors called depositors and buys the relatively risky, high return, and nonliquid securities of borrowers in the form of loans, mortgages, and/or bonds. Note, too, that investor–depositors own claims on the bank itself rather than on the bank’s borrowers.

Financial intermediaries are sometimes categorized according to the type of asset transformations they undertake. As noted above, depository institutions, including commercial banks, savings banks, and credit unions, issue short-term deposits and buy long-term securities. Traditionally, commercial banks specialized in issuing demand, transaction, or checking deposits and making loans to businesses. Savings banks issued time or savings deposits and made mortgage loans to households and businesses, while credit unions issued time deposits and made consumer loans. (Finance companies also specialize in consumer loans but are not considered depository institutions because they raise funds by selling commercial paper, bonds, and equities rather than by issuing deposits.)

Due to deregulationGenerally, deregulation refers to any industry where regulations are eliminated or significantly reduced. In this context, deregulation refers to a series of regulatory reforms of the financial industry undertaken in the 1980s and 1990s., though, the lines between different types of depository institutions have blurred in recent years. Ownership structure, charter terms, and regulatory agencies now represent the easiest way to distinguish between different types of depository institutions. Almost all commercial and many savings banks are joint-stock corporations. In other words, stockholders own them. Some savings banks and all credit unions are mutual corporations and hence are owned by those who have made deposits with them.

Insurance companies are also divided between mutual and joint-stock corporations. They issue contracts or policies that mature or come due should some contingency occur, which is a mechanism for spreading and sharing risks. Term life insurance policies pay off if the insured dies within the contract period, while life annuities pay off if the insured is still alive. Health insurance pays when an insured needs medical assistance. Property or casualty insurance, such as fire or automobile insurance, comes due in the event of a loss, like a fire or an accident. Liability insurance pays off when someone is sued for a tort (damages). Insurers invest policyholder premiumsIn this context, a sum paid for an insurance contract. in stocks, corporate and government bonds, and various money market instruments, depending on the nature of the contingencies they insure against. Life insurance companies, for example, invest in longer-term assets than automobile or health insurers because, on average, life insurance claims occur much later than property or health claims. (In the parlance of insurance industry insiders, life insurance has a much longer “tail” than property insurance.)

The third major type of intermediary is the investment company, a category that includes pension and government retirement funds, which transform corporate bonds and stocks into annuities, and mutual funds and money market mutual funds, which transform diverse portfolios of capital and money market instruments, respectively, into nonnegotiableNontransferable to third parties. but easily redeemableIn this context, changeable into cash money by the fund. “shares.”

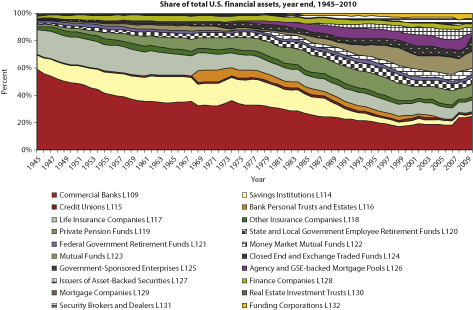

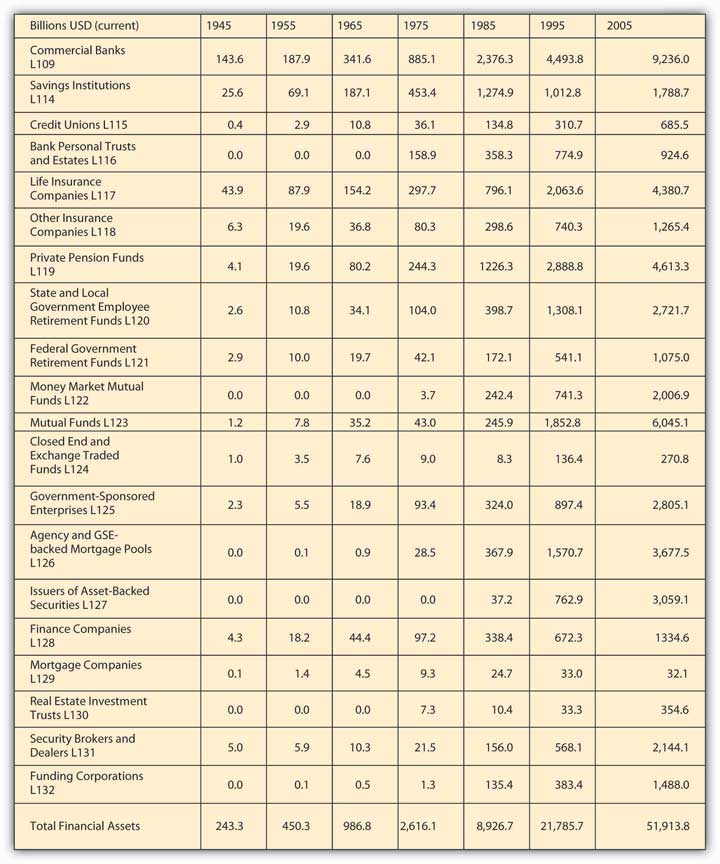

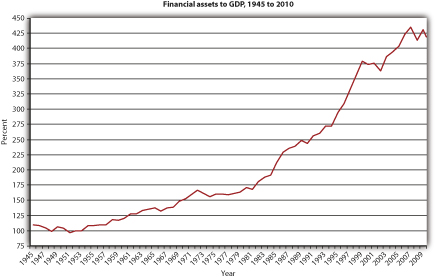

As Figure 2.4 "Share of total U.S. financial assets, year-end, 1945–2010"shows, the relative importance of commercial banks and life insurance companies has waned since World War II due to the proliferation of additional investment options. As Figure 2.5 "Assets of financial intermediaries, selected years, 1945–2005" shows, their decline is relative only; the assets of all major types of intermediaries have grown rapidly over the last six decades. The figures are in current dollars, or dollars not adjusted for inflation, and the U.S. economy has grown significantly since the war, in no small part due to the financial system. Nevertheless, as shown in Figure 2.6 "Financial assets to gross domestic product (GDP), 1945–2010", the assets of financial intermediaries have grown steadily as a percentage of GDPGDP, or gross domestic product, is one of several different measures of aggregate output, the total value of all final goods and services produced in an economy..

Figure 2.4 Share of total U.S. financial assets, year-end, 1945–2010

Figure 2.5 Assets of financial intermediaries, selected years, 1945–2005

Figure 2.6 Financial assets to gross domestic product (GDP), 1945–2010

Financial markets have exhibited similar growth. For example, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA),www.djindexes.com/mdsidx/index.cfm?event=showAverages a mechanism for tracking the prices of the shares of the nation’s most important corporations, grew from less than 200 at the end of World War II to just shy of 700 when John F. Kennedy took office in 1961, to around 1,000 when Ronald Reagan became president twenty years later, to over 3,200 in 1992 and over 10,000 by 1999.www.measuringworth.org/datasets/DJA/ Trading volumes on the New York Stock Exchangewww.nyse.com/ and the NASDAQwww.nasdaq.com/ have likewise soared. In 1945, daily trading volumes rarely exceeded 2 million shares. By 1975, 10 million shares was considered a slow day. By 2005, over 1 billion shares were regularly traded each day.

Key Takeaway

- Financial intermediaries, including depository institutions (commercial banks, savings banks, credit unions) and insurers (life, health, property and casualty), can be grouped by the composition of their balance sheets (nature of their assets and liabilities and the asset transformations they undertake) or their ownership structure, the origin of their corporate charters, and/or the identity of their regulators.