This is “Mortality Risk Management: Individual Life Insurance and Group Life Insurance”, chapter 19 from the book Enterprise and Individual Risk Management (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 19 Mortality Risk Management: Individual Life Insurance and Group Life Insurance

Following Social Security as a foundation to managing the life cycle risks of old age, sickness, accidents, and death, we begin our expedition into the products that help in solving these risks. In this chapter we delve into the life insurance products and the life insurance industry as one separate from the property/casualty insurance industry. As you saw in Chapter 7 "Insurance Operations", the accumulation of a reserve and the pricing of life insurance and annuities are based on mortality tables and life expectancy tables. The health insurance products use morbidity tables and loss data for calculating health and disability rates. In this chapter we will learn about the different life insurance products available—term life, whole life, universal life, variable life, and universal variable life products. The way these products fit into the risk management portfolio of the Smith family is featured in Case 1 of Chapter 23 "Cases in Holistic Risk Management". This chapter concentrates on the life products themselves.

While mortality rates keep improving (as we discussed in Chapter 17 "Life Cycle Financial Risks"), extreme health catastrophes can reverse the trend for brief periods. At various points in human history, mortality rates worsened as extreme health catastrophes occurred. For example, the mortality rate changed dramatically in 1918 when millions of people died from the flu pandemic. The potential for an avian flu pandemic in 2006 led to estimated life insurance claims of up to $133 billion under the most extreme scenario. The young and the elderly are those affected most by the flu. Because these age cohorts usually have less life insurance coverage, the general mortality impact may be even greater than the life claims estimates.Insurance Information Institute (III), “Moderate Avian Flu Pandemic Similar to 1957 and 1968 Outbreaks Could Cost U.S. Life Insurers $31 Billion in Additional Claims,” Press Release, January 17, 2006, http://www.iii.org/media/updates/press.748721/ (accessed April 10, 2009).

Life insurance can be thought of as a contract providing a hedge against an untimely death. When purchasing life insurance, the policyowner buys a contract for the future delivery of dollars. This also provides liquidity. The death, whenever it occurs, will create , such as funeral costs and debt payment, and estate taxes if the estate is large enough, that must be paid immediately. Most people, no matter how wealthy, will not have this much cash on hand. Life insurance provides the necessary liquidity because its payment is triggered by death. Smart decisions about life insurance require understanding both the nature of life insurance and the different types of products available. In this chapter we cover the most widely used products.

The topics covered in this chapter include the following:

- Links

- How life insurance works

- Life insurance products: term insurance, universal life, variable life, variable universal life, and current assumption whole life

- Taxation, major policy provisions, riders, and adjusting life insurance for inflation

- Group life insurance

Links

For our holistic risk management, we need to look at all sources of coverages available. Understanding each type of coverage will complete our ability to manage our risk. In this chapter we delve into the various types of life insurance coverage that are available in the market. Some focus on covering the risk of mortality alone, while others also offer a savings element along with covering the risk of dying. This means that at any point in time, there is a cash value to the policy. This savings element is critical to the choices we make among policies such as whole life, universal life, or universal variable life policies. Our savings with insurance companies, via life products or annuities, makes this industry one of the largest financial intermediaries globally. As explained in Chapter 7 "Insurance Operations", the investment part of the operation of an insurer is as important as the underwriting part. Investments allow insurance companies to postprofits even when underwriting at a loss. In the life/health industry, investments are crucial to both financial performance and solvency. (Read how the industry is affected by poor investment returns in the box “The Life/Health Industry in the Economic Recession of 2008–2009” which appears later in this chapter.)

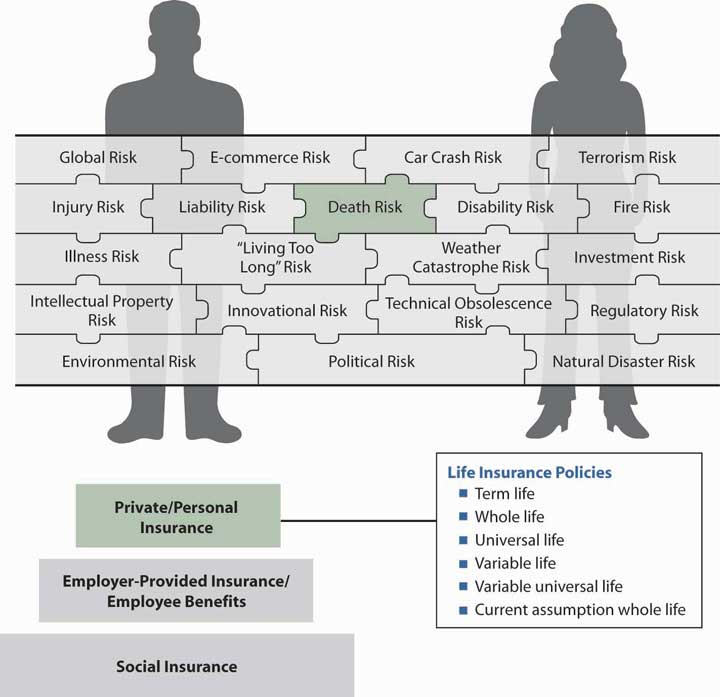

Figure 19.1 The Links between Holistic Risk Puzzle Pieces and Life Insurance Policies

In this chapter, we drill down into the life insurance policies, but this is just a piece of the products puzzle that helps us complete the bigger picture of our risks. All of the steps of the three-step structure in Figure 19.1 "The Links between Holistic Risk Puzzle Pieces and Life Insurance Policies" include some elements of death benefits coverage. In this chapter we delve into the top step for the different types of individual life coverage. Figure 19.1 "The Links between Holistic Risk Puzzle Pieces and Life Insurance Policies" provides us with the connection between the life policies of this chapter and the holistic risk picture.

19.1 How Life Insurance Works

Learning Objectives

In this section we elaborate on the manner in which life insurance products are able to pay the promised benefit:

- The concept of pooling in life insurance

- Adjustments reflected in life insurance premiums

- The cost-prohibitive nature of renewable term life insurance over time

- Level premiums in whole life policies

- How level premiums create reserve and protection

Life insurance, like other forms of insurance, is based on three concepts: pooling many exposures into a group, accumulating a fund through contributions (premiums) from the members of the group, and paying from this fund for the losses of those who die each year. That is, life insurance involves the group sharing of individual losses. The individual transfers the risk of dying to the pool by paying the premiums. To set premium rates, the insurer must be able to calculate the probability of death at various ages among its insureds, based on pooling. The simplest illustration of pooling is one-year term life insurance. If an insurer promises to pay $100,000 at the death of each insured who dies during the year, it must collect enough money to pay the claims. If past experience indicates that 0.1 percent of a group of young people will die during the year, one death may be expected for every 1,000 persons in the group. If a group of 300,000 is insured, 300 claims (300,000 × .001) are expected. Because each contract is for $100,000, the total expected amount of death claims is $30 million (300 claims × $100,000). To collect enough premiums to cover mortality costs (the cost of claims), the insurer must collect $100 per policyowner ($30 million in claims / 300,000 policyowners).

Other Premium Elements

In addition to covering mortality costs, a life insurance premium must reflect several adjustments. First, the premium is reduced to recognize that the insurer expects to earn investment income on premiums paid in advance. In this manner, most of an insurer’s investment income benefits consumers. Second, the premium is increased to cover the insurer’s marketing and administrative expenses. Taxes levied on the insurer must also be recovered. In calculating premiums, an actuary usually increases the premium to cover the insurer’s risk and expected profits. Risk charges cover any deviations above the predicted level of losses and expenses. The major premium elementsAdjustments made in life insurance rates for items such as investment income, marketing/administrative costs, taxes, and actuarial risks. for term life insurance and the actual prediction of deaths and the estimation of other premium elements are complicated actuarial processes (see Chapter 7 "Insurance Operations").

The mortality curve discussed in Chapter 7 "Insurance Operations" and Chapter 17 "Life Cycle Financial Risks" also shows why life insurance for a term of one year costs relatively little for young people. The probability that a death benefit payment will be made during that year is very low. The mortality curve also indicates why the cost of yearly renewable term life insuranceTerm life insurance purchased on a year-by-year basis., purchased on a year-by-year basis, becomes prohibitive for most people’s budgets beyond the middle years. The theory of insurance is that the losses of the few can be paid for by relatively small contributions from the many. If, however, a large percentage of those in the group suffer losses (say, because all members of the group are old), the burden on one’s budget becomes too great, substantial adverse selection is experienced, and the insurance mechanism fails.

Level-Premium Plan

The mortality curve shows that yearly renewable term life insurance, where premiums increase each year as mortality increases, becomes prohibitively expensive at advanced ages. For example, the mortality table shows a mortality rate of 0.06419 for a male age seventy-five. Thus, just the mortality element of the annual premium for a $100,000 yearly renewable term life insurance policy would be $6,419 (0.06419 × $100,000). At age ninety, ignoring other premium elements and adverse selection, the mortality cost would be $22,177 (0.22177 × −$100,000). From a budget perspective, this high cost, coupled with adverse selection, can leave the insurer with a group of insureds whose mortality is even higher than would be anticipated in the absence of adverse selection. Healthy people tend to drop the insurance, while unhealthy people try to pay premiums because they think their beneficiaries may soon have a claim. This behavior is built into renewal rates on term insurance, resulting in renewal rates that rise substantially above rates for new term insurance for healthy people of the same age. A system of spreading the cost for life insurance protection, over a long period or for the entire life span, without a rise in premiums, is essential for most individuals. This is the function of level-premium life insurance.

A level premiumIn life insurance, a premium that remains constant throughout the premium-paying period instead of rising from year to year. remains constant throughout the premium-paying period, instead of rising from year to year. Mathematically, the level premium is the amount of the constant periodic payment over a specified period (ending before the specified date in the event of death); it is equivalent to a hypothetical single premium that could be paid at the beginning of the contract, discounting for interest and mortality. The hypothetical single premium at the beginning can be thought of as similar to a mortgage that is paid for by periodic level premiums.

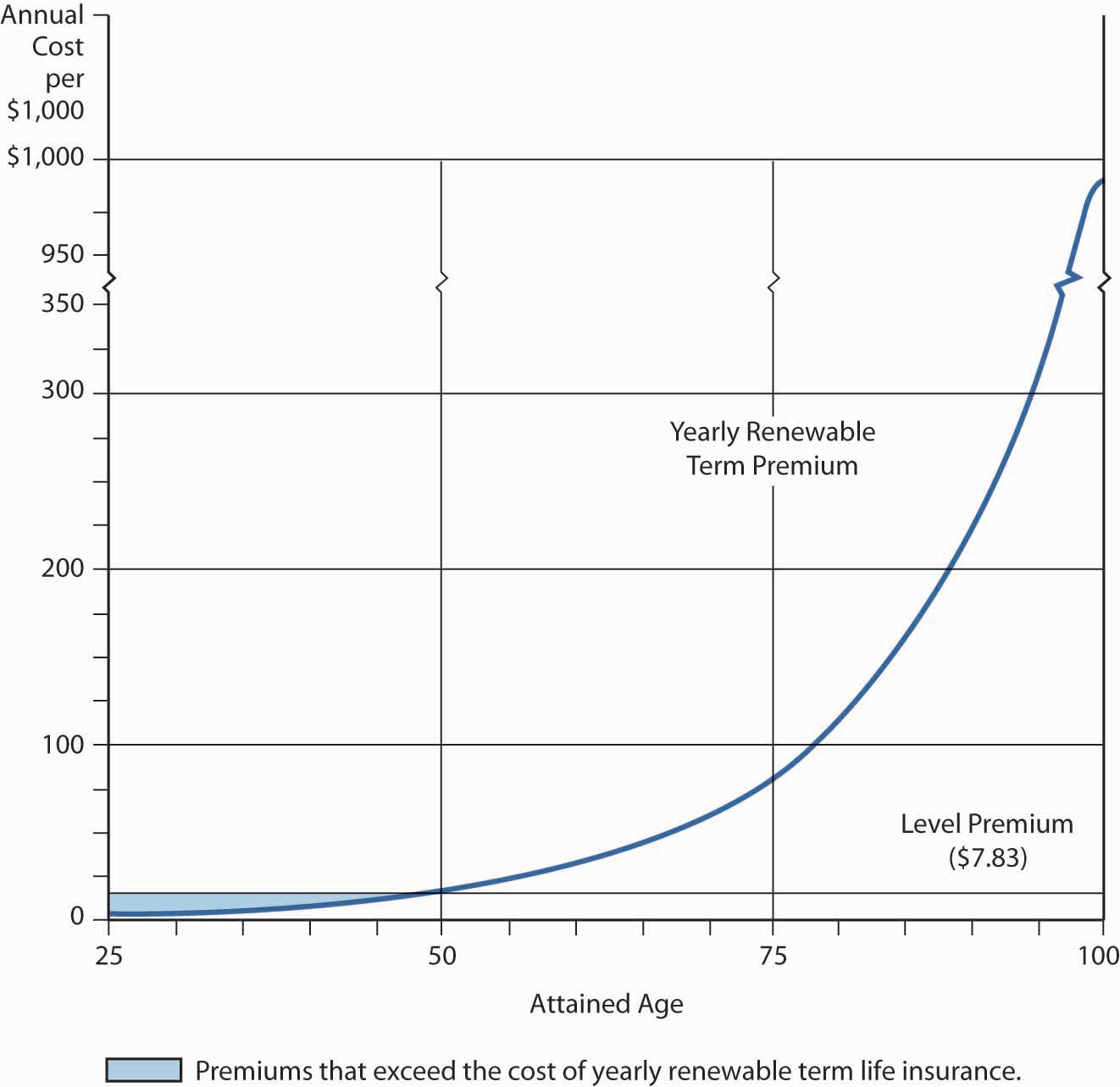

As Figure 19.2 "Yearly Renewable Term Premium and Level Premium for Ordinary Life (Issued at Age Twenty-Five)" shows, the level premium for an ordinary (whole) life policy (which provides lifetime protection) is issued at age twenty-five in the illustration and is greater during the early years than are the premiums for a yearly renewable term policy for the same period. The excess (see the shaded area between age twenty-five and a little before age fifty in Figure 19.2 "Yearly Renewable Term Premium and Level Premium for Ordinary Life (Issued at Age Twenty-Five)") and its investment earnings are available to help pay claims as they occur. This accumulation of funds, combined with a decreasing amount of true insurance protection (which is the net amount at risk to the insurance mechanism), makes possible a premium that remains level even though the probability of death rises as the insured grows older. In later years, the true cost of insurance protection (the probability of death at a particular age times the decreased amount of protection) is paid for by the level premium plus a portion of the investment earnings produced by the policy’s cash value. In summary, the level premium is higher than necessary to pay claims and other expenses during the early years of the contract, but less than the cost of protection equal to the total death benefit during the later years. The concept of a level premium is basic to an understanding of financing death benefits at advanced ages.

The accumulation of funds is a mathematical side effect of leveling the premium to accommodate consumers’ budgets. Beginning in the 1950s, however, insurers began to refer to the accumulated funds of level premium life insurance policies as cash valueAccumulated funds of level premium life insurance policies as that can be utilized to meet various savings needs. that could meet various savings needs. Today, the payment of premiums greater than the amount required to pay for a yearly renewable term policy often is motivated, at least in the minds of consumers, by the objective of creating savings or investment funds.

Figure 19.2 Yearly Renewable Term Premium and Level Premium for Ordinary Life (Issued at Age Twenty-Five)

Based on nonsmoker rates for a $50,000 policy with a selected company.

Effects of the Level Premium Plan

From an economic standpoint, the level premium plan does two things. First, the insurer offers an installment payment plan with equal payments over time. Second, the level premium policies are made up of two elements: protection and investment.

As discussed, although the periodic premium payments exceed death benefits and other expenses for an insured group during the early years of the policy, they fall short during later years (see Figure 19.2 "Yearly Renewable Term Premium and Level Premium for Ordinary Life (Issued at Age Twenty-Five)"); consequently, the insurer accumulates a reserveIn life insurance, funds accumulated to offset the deficiency of periodic premium payments falling short of providing promised death benefits in later years of a policy. to offset this deficiency. The insurer’s reserve is similar in amount, but not identical, to the sum of cash values for the insured group. The reserve is a liability on the insurer’s balance sheet, representing the insurer’s obligation and reflecting the extent to which future premiums and the insurer’s assumed investment income will not be sufficient to cover the present value of future claims on a policy. At any point, the present value of the reserve fund, future investment earnings, and future premiums are sufficient to pay the present value of all future death claims for a group of insureds. When an insured dies, the insurer is obligated to pay the beneficiary the face amount (death benefit) of the policy. Part of this payment is an amount equal to the reserve.

The difference between the reserve at any point in time and the face amount of the policy is known as the net amount at riskFor the insurer, the difference between the funding reserve at any point in time and the face amount of the policy. for the insurer and as the protection elementFor the insured, the difference between the funding reserve at any point in time and the face amount of the policy. for the insured. As Figure 19.2 "Yearly Renewable Term Premium and Level Premium for Ordinary Life (Issued at Age Twenty-Five)" illustrates, this element declines each year because the reserve (investment or cash value) increases. The protection/net-amount-at-risk element is analogous to decreasing term insurance. All level premium life policies have a combination of cash value and protection.

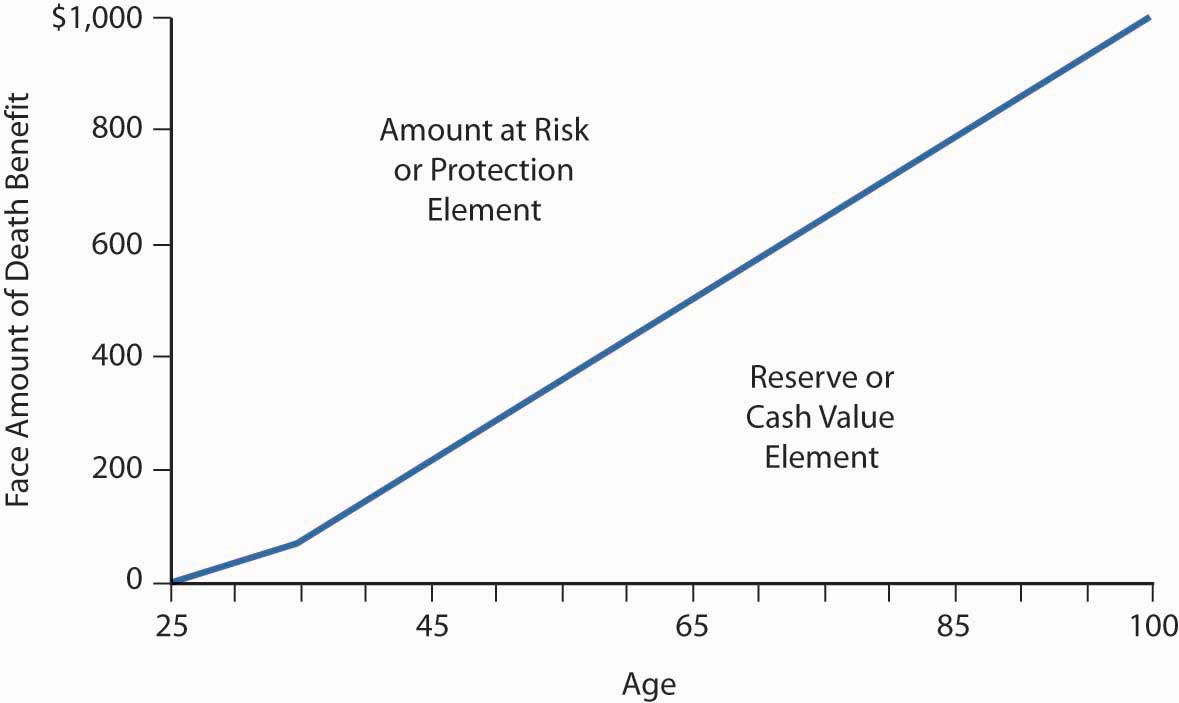

The amount at risk for the insurer (that is, the protection element) decreases as the cash value element increases with age; thus, less true insurance (protection) is purchased each year. This decreasing amount of insurance is one of the reasons why the annual cost of pure insurance (that is, the protection element) to the insurer is less than the sum of the level premium plus investment earnings, even at advanced ages when mortality rates significantly exceed the premium per $1,000 of death benefit. Over time, the growing amount of investment earnings (due to increasing cash value) more than offsets the inadequacy of the level premium. The periodic addition of part of these investment earnings to cash value explains why the cash value in the policy continues to grow throughout the life of the contract (see Figure 19.3 "Proportion of Protection and Cash Value in Ordinary Life Contract (Issued to a Male Age Twenty-Five)").

Figure 19.3 Proportion of Protection and Cash Value in Ordinary Life Contract (Issued to a Male Age Twenty-Five)

This graph shows the cash value (investment) figures for a selected ordinary life policy. The insurer’s reserve would be slightly higher than the cash value in the early contract years.

From an insurer’s perspective, the reserve is a liability that will have to be paid when the insured either dies or surrenders the policy. The separation of a whole life policy into protection and investment elements is an economic or personal finance concept rather than an actuarial one. Actuaries deal with large groups of insureds rather than individual policies; they look at an individual policy as an indivisible contract.

The cash value is classified as an asset on the policyholder’s personal balance sheet because it is the policy owner’s money. There are three ways to realize the cash value:

- Surrender (discontinue) the policy and receive the cash value as a refund

- Take a loan for an amount not to exceed the cash value

- Leave the cash value in the contract and eventually let it mature as part of the death claim

Key Takeaways

In this section you studied mechanisms that allow for the provision of life insurance:

- The concept of pooling is critical to life insurance because the losses of the few can be paid for by relatively small contributions from the many.

- Life insurance premiums are adjusted for investment income, marketing/administrative costs, taxes, and actuarial risks.

- Yearly renewable term life insurance is cost-prohibitive in later years due to adverse selection and the increased probability of death.

- In whole life policies, the level premium is higher than necessary to pay claims and other expenses during the early years of the contract, but less than the cost of protection equal to the total death benefit during the later years.

- Level premium policies allow for cash value accumulation.

- The difference between the reserve and the face amount of the life insurance policy is the net amount at risk for the insurer and the protection element for the insured.

- Insureds may realize their cash value by surrendering the policy, taking out a loan, or letting the policy mature as part of the policy’s death benefit.

Discussion Questions

- Why does yearly renewable term life become cost prohibitive over time?

- Explain why an investment (cash value) segment becomes part of a level premium life insurance contract.

- Explain the nature of the reserve an insurer accumulates in connection with its level premium life insurance policies.

- What are the options with cash surrender value?

19.2 Life Insurance Market Conditions and Life Insurance Products

Learning Objectives

In this section we elaborate on the following:

- Market condition in 2008–2009

- Term life insurance

- Whole life insurance

- Universal life insurance

- Variable life insurance

- Variable universal life insurance

- Current assumption whole life insurance

Market Conditions

The life insurance industry is one of the largest industries in the world. Premiums for life, health, and annuity grew by 5.7 percent from $583.6 billion in 2006 to $616.7 billion in 2007 in the United States.Insurance Information Institute (III), The Insurance Fact Book, 2009, 19. This section concentrates on the life products sold to individuals. A comprehensive summary of these products is available in Table 19.1 "Characteristics of Major Types of Life Insurance Policies". The trend is toward lower life insurance rates for all types of life insurance products. Improvements in mortality rates have accounted for lower expected rates. This improvement was also highlighted in Chapter 17 "Life Cycle Financial Risks". The life/health industry’s condition deteriorated during the economic recession beginning in December 2007. These problems are detailed in the box “The Life/Health Industry in the Economic Recession of 2008–2009.”

The Life/Health Industry in the Economic Recession of 2008–2009

Unlike property/casualty carriers, the prosperity of life insurance companies is closely linked to the health of the broader financial network. Investments make up a significant portion of industry profits, and they are the driving component behind product delivery. Because of the economic recession, life annuities promising minimum payments (discussed extensively in Chapter 21 "Employment-Based and Individual Longevity Risk Management") are particularly strained; in many cases, their guarantees are no longer supported by underlying investments. Those underlying investments consist of stocks, commercial mortgages, mortgage-backed securities (or MBSs, which were covered in the box “Problem Investments and the Credit Crisis” in Chapter 7 "Insurance Operations"), and corporate bonds. Market devaluation, default, or interest rate reductions have harmed all of these funding sources. Consider that the asset mix of life insurers in 2007 included $387.5 billion worth of MBSs; by way of comparison, the property and casualty insurance industry held $125.8 billion.

Recall from Chapter 5 "The Evolution of Risk Management: Enterprise Risk Management" and Chapter 7 "Insurance Operations" that insurers’ net worth is expressed in the form of capital and surplus (assets minus liabilities). Insurers must have capital that is sufficient to satisfy their liabilities (mainly in the form of loss reserves). In 2008, surplus declined by 4.7 percent for the top one hundred life insurers. This drop was mitigated somewhat, however, by successfully raising new capital in 2008. Nonetheless, investors will be none too pleased with the return on equity ratio of −0.3 percent, down from 12.8 percent in 2007. With little bargaining power, the industry may be able to raise new capital in the future only at less-than-favorable terms. Conning Research and Consulting estimates that surplus for the entire industry could be off by as much as 24 percent in 2008. Low interest rates and investments that are not simply depressed, but highly volatile, are cited as the reasons for the industry’s shrinking assets and surplus.

Twelve life insurers, including MetLife, Hartford Financial Group, and Prudential, have applied for aid through the government’s Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). TARP, signed into law October 2, 2008, pledges $700 billion worth of federal spending toward the purchase of assets and equities of imperiled financial institutions. As of this writing, the U.S. Treasury has decided to include insurers in the TARP program. (AIG is a special case, in a class all its own.) At the end of 2008, unrealized losses amounted to $30 billion for MetLife, $15 billion for Hartford, and $11 billion for Prudential. Nonetheless, company officials insist that their firms are adequately capitalized to meet current liabilities.

On February 27, 2009, in line with previous moves by fellow rating agencies Fitch and Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s (S&P) lowered its financial strength and credit ratings on ten groups of U.S. life insurers and seven life insurance holding companies, respectively. Organizations implicated include Metlife, Hartford, Genworth Financial, Prudential, and Pacific LifeCorp. S&P’s analysis focused on poor investment performance, equity declines, and company earnings volatility. On the bright side, Massachusetts Mutual Life, New York Life Insurance, and Northwestern Mutual in particular have retained triple-A financial strength ratings as of this writing. After these downgrades, the American Council of Life Insurers (ACLI) lobbied the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) for lower capital and reserve requirements. The ACLI, a trade organization of 340 member companies accounting for 93 percent of the life insurance industry’s U.S. assets, said that their proposal would give a financial cushion and restore some operating flexibility. The NAIC denied the request on January 29, 2009, with president and New Hampshire insurance commissioner Roger Sevigny stating, “So far the insurance industry is in much better condition than most of the rest of the financial services sector because of strong state solvency regulations.”

With respect to the health segment, there has been a longstanding assumption that health care was a recession-proof industry due to the fact that people become ill and need medical services regardless of economic circumstances. The current recession is casting doubt on this notion. As of this writing, 60 percent of Americans have health insurance through employer-sponsored plans. The recent advent of high-deductible health plans and their adoption by employers has increased personal responsibility for covering health care expenses traditionally paid by insurers. (Both employer-sponsored health options and high-deductible health plans are covered in Chapter 22 "Employment and Individual Health Risk Management".) Financially strapped employees are thus forced to choose between paying for medical services or paying their mortgages. On the one hand, the delaying and avoidance of medical services by insureds could bode well for health insurers’ loss experience. At the same time, however, with unemployment rates at their highest since 1982, the overall insured population has decreased over the course of the recession. To quantify, the Center for American Progress estimates that 4 million Americans have lost their health insurance since the recession began; up to 14,000 people could be losing coverage every day. The Center correlates each 1 percentage point rise in the unemployment rate with 2.4 million Americans losing employer-sponsored health insurance. Individual health insurance plans are an option, but they are frequently cost-prohibitive to the unemployed unless they are young and in the healthy pool. Those who do remain insured but reduce their consumption of medical services have less demand for health insurance. Consequently, they could drop all but the most basic and necessary health coverage options. Therefore, it is difficult to imagine potential improvements in loss experience offsetting the effects of a shrinking population of insureds.

As further evidence, consider that the top eight health insurance plans in the United States cover 58 percent of the insured population. These insurers have faced challenges over the course of the recession. For example, UnitedHealth Group saw the profit margins on its Health Care Services unit fall from 9.3 percent to 6.6 percent between September 30, 2007, and June 30, 2008. This may not seem significant, but stable profit margins help to contain premium costs in health insurance. The top eight plans have also experienced slowdowns in enrollment growth, a trend that could see enrollment contract as the recession persists.

In response to recessionary pressures, the life/health industry has scaled back on aggressive product development efforts to save costs and meet changing consumer demands. Life insurers are reporting an increasing preference among clients for term rather than permanent insurance. Insureds are also cutting the face value of their policies to reduce premiums. President of Genworth Retirement Services Chris Grady stressed, “The industry has to develop simple retirement income solutions, simple processes and simple marketing” to cope with current market conditions. To their advantage, life insurers’ needs for new capital are partially subsidized by highly liquid premium revenues. Fortunately, the fundamental drive for the security provided by life insurance is strong, and especially so during uncertain times. As for health insurance, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions expects that individuals will delay primary and preventive care, people with high-deductible health plans will put off making payments, and medical debt bankruptcies will rise. Insurers will adjust by shifting more costs to insureds in the form of higher premiums, deductibles, and copayments and by enacting stricter policy provisions.

On March 12, 2009, the Wall Street Journal reported that the Dow Jones Wilshire U.S. Life Insurance Index had fallen 59 percent for the year to date. For the life/health segment, the recession did not hit full-force until the fourth quarter of 2008 due to high losses from investments. Because of accounting rules, the impact of these losses may not be realized on insurers’ books until late 2009 into 2010. FBR Capital Markets estimated that realized credit losses over the preceding two years could top $19.2 billion, exceeding the industry’s projected excess capital of $17.5 billion through 2010. If such a shortfall materializes, it will entail raising new capital, government intervention, or dissolution of distressed companies. Going forward, Conning Research and Consulting predicts significant consolidation within the industry. With life insurers holding a reported 18 percent of all outstanding corporate bonds, the health of capital markets is highly dependent on the activities of life insurers. The 63 percent decline in private bond and equity purchases by life companies in the fourth quarter of 2008 certainly contributed to the depression of capital markets, which is projected to persist until investment activity improves. Similarly, with health care expenditures accounting for 17 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), recovery of the overall U.S. economy is projected to be influenced by the performance of the health industry. The Obama administration has targeted health care as a major area of reform, and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 contains some provisions for health care. These and other efforts will be discussed in Chapter 22 "Employment and Individual Health Risk Management".

Sources: “Analysis Shows Industry Income Down Sharply,” National Underwriter Life/Health Edition, March 5, 2009, http://www.lifeandhealthinsurancenews.com/News/2009/3/Pages/Analysis-Shows-Industry- Income-Down-Sharply.aspx, accessed March 12, 2009; “Recession’s Impact to Stay with Life Insurance Industry for Some Time, Study Says,” Insurance & Financial Advisor (IFA), January 15, 2009, http://www.ifawebnews.com/articles/2009/01/15/news/life/doc496b5d961a699473705621.txt, accessed March 12, 2009; “Conning Research: Life Insurance Industry Forecast—Financial Crisis Will Impact Industry Results Through 2010,” Reuters, January 7, 2009, http://www.reuters.com/article/pressRelease/idUS141575+07-Jan-2009+PRN20090107, accessed March 12, 2009; Scott Patterson and Leslie Scism, “The Next Big Bailout Decision: Insurers,” Wall Street Journal, March 12, 2009, A1; Stephen Taub, “S&P Less Sure of Life Insurance Industry,” CFO, February 27, 2009, http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/13209064/?f=rsspage, accessed March 12, 2009; Keith L. Martin, “State Regulators Deny Life Insurance Industry Request to Lower Capital and Surplus Standards,” Insurance & Financial Advisor (IFA), February 2, 2009, http://www.ifawebnews.com/articles/2009/02/02/news/life/doc49836329444a1723733499.txt, accessed March 12, 2009; Catherine Arnst, “Health Care: Not So Recession-Proof,” BusinessWeek, March 25, 2008, http://www.businessweek.com/technology/content/mar2008/tc20080324_828167.htm?chan=top+news_top+news+index_top+story, accessed March 12, 20009; Meha Ahmad, “Job Losses Leave More Americans Without Health Insurance,” Life and Health Insurance Foundation for Education, January 13, 2009, http://www.lifehappens.org/blog/p,154/#more-154, accessed March 12, 2009; Mary Beth Lehman, “Report: 4 Million Americans Lost Health Insurance Since Recession Began,” Business Review, February 22, 2009; http://www.bizjournals.com/albany/stories/2009/02/16/daily58.html, accessed March 12, 2009; “Top Health Plans Feel Recession According to Mark Farrah Associates,” Reuters, February 19, 2009, http://74.125.47.132/search?q=cache:CK-PYvd3vZUJ:http://www.reuters.com/article/pressRelease/idUS225967%2B19- Feb-2009%2BBW20090219+health+insurance+industry+recession&cd= 21&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us, accessed March 12, 2009; Linda Koco, “All Product Eyes Will Fix on the Economy in 2009,” National Underwriter Life/Health Edition, January 5, 2009, http://www.lifeandhealthinsurancenews.com/Issues/2009/January%205%202009/Pages/All-Product-Eyes-Will-Fix-On-The-Economy-In-2009.aspx, accessed March 12, 2009; Scott Patterson, “Insurers Face More Losses,” Wall Street Journal, March 12, 2009, http://blogs.wsj.com/marketbeat/2009/03/12/insurers-face-more-losses/, accessed March 12, 2009.

Term Insurance

Term life insuranceProvides coverage for a specified period, called the policy’s term (or duration). provides protection for a specified period, called the policy’s term (or duration). When a company issues a one-year term life policy, it promises to pay the face amount of the policy in the event of death during that year.

Duration

The length of term policies varies; common terms are one, five, ten, fifteen, and twenty years. Term policies are often not renewable beyond age sixty-five or seventy because of adverse selection that increases with age. Increasingly, however, yearly renewable term policies are renewable to age ninety-five or one hundred, although it would be unusual for a policy to stay in effect at advanced ages because of the amount of the premium. Yearly renewable term policies are subject to high lapse ratesIn term life insurance, failure to renew policies. (that is, failure to be renewed) and low profitability for the insurer.

Short-term life insurance policies involve no investment element. Long-term contracts (e.g., term to age sixty-five), when accompanied by a level premium, can accumulate a small cash value element in the early years, but this is depleted during the latter part of the term because then the cost of mortality exceeds the sum of the level premium and the investment earnings. Two options are typically available with term insurance sold directly to individuals: renewability and convertibility.

Table 19.1 Characteristics of Major Types of Life Insurance Policies

| Distinguishing Feature | Premiums | Cash Value | Death Benefit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Term life | Provides protection for a specific period (term) | Fixed, but increase at each renewal | None, thus no provision for loans or withdrawals | Pays face amount of policy if death occurs within term |

| Whole life | Lifetime protection: as long as premiums are paid, policy stays in force | Fixed | Guaranteed | Pays face amount if policy is in force when death occurs |

| Universal life | Guaranteed minimum interest rate on the investments accumulated in the accounts. Interest rates are based on bonds only (not stocks) and can be higher than the minimum guaranteed | Flexible, set by policyholder; used to pay mortality rates and expenses, then remainder is invested | Depends on the account value minus surrender charges |

Option A: maintains level death benefit Option B: face amount increases as accumulated cash value grows |

| Variable life | The “mutual fund” policy, intended to keep death benefits apace with inflation; technically, a security as well as insurance | Fixed | Not guaranteed; depends on investment performance of stocks | Minimum face amount that can be greater as cash value changes |

| Variable universal life | Combines the premium and death benefit flexibility of a universal life policy with the investment choices in stocks of variable life | Flexible, as in universal life | Not guaranteed; depends on investment performance of stocks | Same options are universal life |

Renewability

If the policyholder wishes to continue the protection for more than one term, the insurer will require a new application and new evidence of insurability. The risk of being turned down may be handled by purchasing renewable term insurance. The renewability optionIn term life insurance, gives the right to renew the policy for a specified number of additional periods of protection at a predetermined schedule of premium rates without new evidence of insurability. gives the policyholder the right to renew the life insurance policy for a specified number of additional periods of protection, at a predetermined schedule of premium rates, without new evidence of insurability. Renewability protects insurability for the period specified. After that period has elapsed, the insured must again submit a new application and prove insurability.

Each time the policy is renewed, the premium increases because of the insured’s increasing age. Because the least healthy tend to renew and the most healthy tend to discontinue, the renewable feature increases the cost of protection. The renewable feature, however, is valuable in term life insurance.

Convertibility

A term life policy with a convertibility optionIn term life insurance, provides the right to convert the policy to a whole life or another type of insurance before a specified time without proving insurability. provides the right to convert the term policy to a whole life or another type of insurance, before a specified time, without proving insurability. If, for example, at age twenty-eight you buy a term policy renewable to age sixty-five and convertible for twenty years, you may renew each year for several years and then, perhaps at age thirty-six, decide you prefer cash value life insurance. Your motivation may be that the premium, though higher than that of the term policy at the age of conversion, will remain the same year after year; the policy can be kept in force indefinitely; or you may want to include cash values among your investments. If you become uninsurable or insurable only at higher-than-standard (called substandard) rates, you will find the convertibility feature very valuable.

Most life insurance conversions are made at attained age premium ratesIn life insurance conversion, when the premium for the new policy is based on the age at the time of the conversion., meaning that the premium for the new policy is based on the age at the time of the conversion. The insured or policyowner pays the same rate as anyone else who can qualify for standard rates based on good health and other insurability factors. The option results in no questions about your insurability.

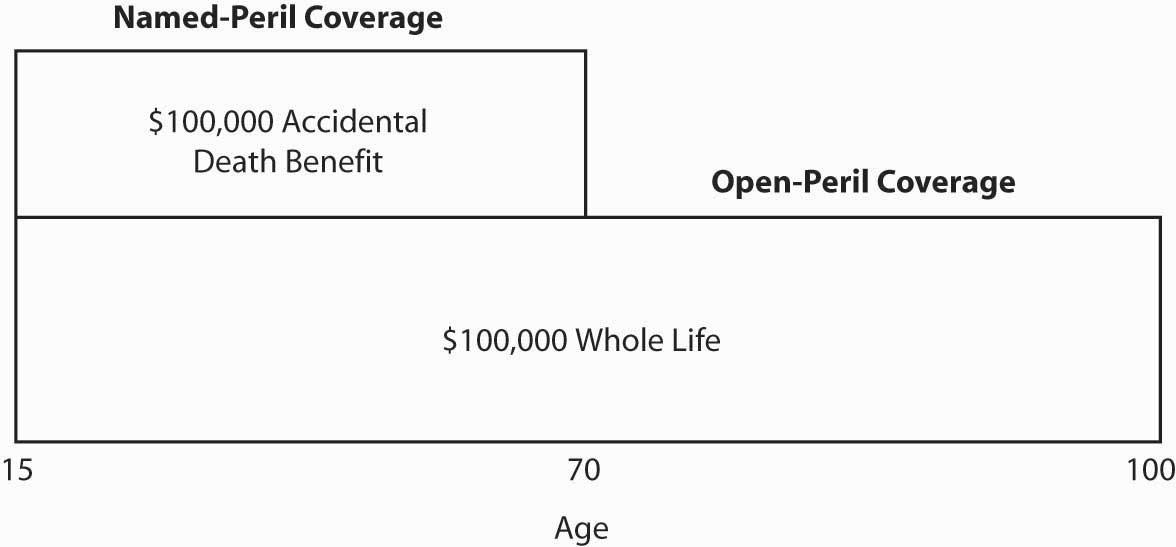

Death Benefit Pattern

The death benefit in a term policy remains level, decreases, or increases over time. Each pattern of protection fits specific needs. For example, a decreasing term policy may be used as collateral for a loan on which the principal is being reduced by periodic payments. An increasing amount of protection helps maintain purchasing power during inflation. The increasing benefit is likely to be sold as a rider to a level benefit policy.

Mortgage protection insuranceDecreasing term insurance; with each mortgage payment, the face value of the insurance decreases to correspond to the amount of the loan that is outstanding. is decreasing term insurance; with each mortgage payment, the face value of the insurance decreases to correspond to the amount of the loan that is outstanding. Otherwise, mortgage protection is like other decreasing term policies.Before buying a mortgage protection policy, consider the pros and cons of paying off your mortgage at the time of death. Will your spouse’s income be sufficient to meet the mortgage payments? Is the interest rate likely to be attractive in the future? Will the after-tax interest rate be less than the rate of growth in the value of the house, resulting in favorable leverage? Credit life insurance is similar to mortgage protection. In credit life insuranceProvides that the death benefit changes, up or down, as the balance changes on an installment loan or other type of consumer loan., the death benefit changes, up or down, as the balance changes on an installment loan or other type of consumer loan.

Premium Patterns

An insurer’s rates for nonsmokers may be 40 percent or so lower than those for smokers. Rates for women are less than for men (see the box “Should Life Insurance Rates Be Based on Gender?” in Chapter 17 "Life Cycle Financial Risks"). The yearly renewable term contract usually has a table of premiums that increase each year as the insured ages and as time elapses since insurability was established.

Reentry termIn life insurance, allows the insured to re-demonstrate insurability periodically, perhaps every five years, and qualify for a new (lower) select category of rates that are not initially loaded for adverse selection. allows the insured to demonstrate insurability periodically, perhaps every five years, and qualify for a new (lower) select category of rates that are not initially loaded for adverse selection. If the insured cannot qualify for the new rates, usually because of worsening health, he or she can either pay the higher rates of the initial premium table (ultimate rates) or drop the policy and try to find better rates with another insurer.

Summary: Features of Term Life

In summary, in term life we see the following features (see also Table 19.1 "Characteristics of Major Types of Life Insurance Policies"):

- Death benefits: level or decreasing

- Cash value: none

- Premiums: increase at each renewal

- Policy loans: not allowed

- Partial withdrawals: not allowed

- Surrender charges: none

Whole Life Insurance

Whole life insuranceProvides for payment of the face value upon death regardless of when the death may occur; “permanent insurance”, as its name suggests, provides for payment of the face value upon death regardless of when the death may occur. As long as the premiums are paid, the policy stays in force. Thus, whole life insurance is also referred to as permanent insurance. This ability to maintain the policy throughout one’s life, instead of a specific term, is the key characteristic of whole life insurance.

There are three traditional types of whole life insurance: (1) ordinary or straight life, (2) limited-payment life, and (3) single-premium life. The differences among them is in the arrangements for premium payment. (See Chapter 26 "Appendix C" for a sample straight whole life policy.)

Straight Life

The premiums for a straight lifeForm of whole life insurance where premiums are paid in equal periodic amounts over the life of the insured. policy are paid in equal periodic amounts over the life of the insured. The rate is based on the assumption that the insured will live to an advanced age (such as age ninety or 100). In effect, the insured is buying the policy on an installment basis and the installments are spread over the balance of the lifetime, as explained earlier in our discussion of the level premium concept. This provides the lowest possible level outlay for permanent protection.

As shown in Figure 19.3 "Proportion of Protection and Cash Value in Ordinary Life Contract (Issued to a Male Age Twenty-Five)", the level premium policy consists of a protection element and a cash value element. The cash value builds over time, and eventually, when the insured is ninety or one hundred, the cash value will equal the face value of the policy. If the insured is still alive at this advanced age, the insurer will pay the death benefit as if death occurred. By this time, no real insurance element exists. The options available with regard to this value are discussed later in this chapter. A basic straight life policy typically has a face amount (death benefit) that remains level over the lifetime. The pattern can change, however, by using dividends to buy additional amounts of insurance or by purchasing a cost-of-living adjustment rider.

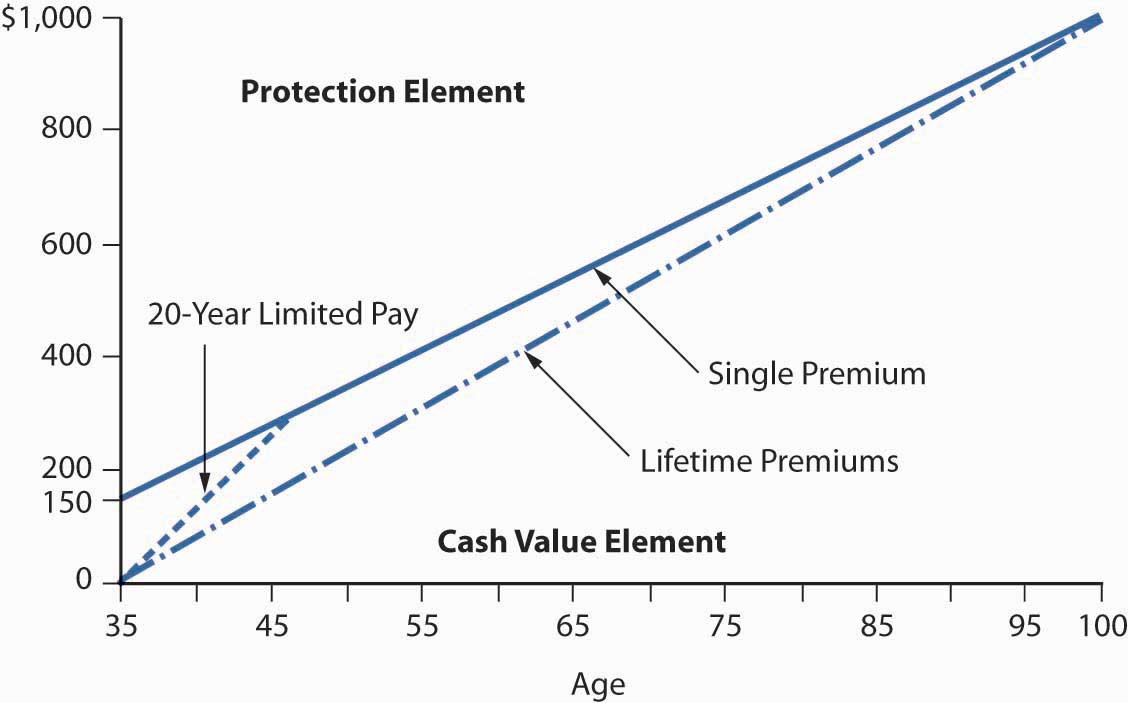

Limited-Payment Life

Like straight life, limited-payment lifeForm of whole life insurance that offers lifetime protection but limits premium payments to a specified period of years or to a specified age; after premiums have been paid during the specified period, the policy remains in force for the balance of life without further premium payment. offers lifetime protection but limits premium payments to a specified period of years or to a specified age. After premiums have been paid during the specified period, the policy remains in force for the balance of the insured’s life without further premium payment. The policy is “paid up.” A twenty-pay life insurance policy becomes paid up after premiums have been paid for twenty years, a life-paid-up-at-sixty-five becomes paid up at age sixty-five, and so on (see Figure 19.4 "Protection and Cash Value Elements for Single-Premium and Installment Forms of Cash Value Life Insurance"). The shorter premium payment period appeals to some buyers. For example, a life-paid-up-at-sixty-five policy ends premiums around the time many people expect to begin living on retirement pay. If the insured dies before the end of the premium-paying period, premium payments stop and the face amount is paid. These policies are mainly sold as business insurance where there is a need to pay fully for a policy by a certain date, such as the time an employee will retire.

Single-Premium Life

Whole life insurance may be bought for a single premium—the ultimate in limited payment. Mathematically, the single premiumForm of life insurance where the only premium paid is an amount equal to the present value of future benefits, with discounts both for investment earnings and mortality. is the present value of future benefits, with discounts both for investment earnings and mortality. Cash and loan values are high compared with policies bought on the installment plan (see Figure 19.4 "Protection and Cash Value Elements for Single-Premium and Installment Forms of Cash Value Life Insurance"). Single-premium life insurance is bought almost exclusively for its investment features; protection is viewed as a secondary benefit of the transaction.

Figure 19.4 Protection and Cash Value Elements for Single-Premium and Installment Forms of Cash Value Life Insurance

Note: Hypothetical values not drawn to scale.

Investment Aspects

The typical buyer of life insurance, however, does not expect to pay income taxes on proceeds from his or her policy. Instead, the expectation is for the policy to mature eventually as a death claim. At that point, all proceeds (protection plus cash value) of life insurance death claims are exempt from income taxes under Section 101(a)(1). In practice, most policies terminate by being lapsed or surrendered prior to death as needs for life insurance change.

Life insurers offer participation in portfolios of moderate-yield investments, such as high-grade industrial bonds, mortgages, real estate, and common stock, in which cash values are invested with potentially no income tax on the realized investment returns. Part of each premium, for all types of cash value life insurance, is used to make payments on the protection element of the contract, but the protection element also has an expected return. This return is equal to the probability of death multiplied by the amount of protection. Thus, the need to pay for protection in order to gain access to the cash value element of a single-premium or other investment-oriented plan should not be viewed as a consumer disadvantage if there is a need for additional life insurance protection. The participation (dividend) feature of a policy has a major effect on its cost and worth.

Participation Feature

Mutual life insurers have always sold their term and cash value life products on a participation basis. Stock life companies have also made limited use of participating policies. Participating whole life contracts pay dividendsPaid by participating whole life contracts to insureds for the purpose of refunding higher-than-necessary premiums and sharing company profits with policyowners. for the purpose of refunding higher-than-necessary premiums and sharing company profits with policyowners. Thus, as investment returns escalate above previous expectations, or as mortality rates decline, the policyowners share in the success of the insurer.

DividendsPaid by participating whole life contracts to insureds for the purpose of refunding higher-than-necessary premiums and sharing company profits with policyowners. allow the sharing of current profits from investments, mortality assumptions, expense estimates, and lapse experience with the policyholder. Investment returns usually have more influence on the size of dividends than do the other factors. The fact that insurer investment portfolios tend to have many medium- and long-term bonds and mortgages that do not turn over quickly creates a substantial lag, however, between the insurer’s realization of higher yields on new investments and the effect of those higher yields on average portfolio returns that affect dividends.

Participating whole life insurance continues to be a major product line for mutual insurers. Sales illustrations are used by agents in presenting the product to the consumer. For products with the participation feature, dividends projected for long periods into the future are a significant part of the sales illustration. Generally, the illustrations are based on the current experience of the insurer with respect to its investment returns, mortality experience, expenses, and lapse rates.

Summary: Features of Whole Life

In summary, in whole life we see the following features (see also Table 19.1 "Characteristics of Major Types of Life Insurance Policies"):

- Death benefits: fixed level

- Cash value: guaranteed amounts

- Premiums: fixed level

- Policy loans: allowed

- Partial withdrawals: not allowed

- Surrender charges: none

Universal Life Insurance

Universal life insurance contracts were introduced to the market in 1979 to bolster the profits of stock insurance companies. Universal life insuranceOffer competitive investment features and the flexibility to meet changing consumer needs by allowing policyholder to change the amount of premium periodically, discontinue premiums and resume them at later date without lapsing the policy, and change the amount of death protection. policies offer competitive investment features and the flexibility to meet changing consumer needs. When expense charges (such as mortality rates) are set at reasonable levels, the investment part of the universal life contract can be competitive on an after-tax basis with money market mutual funds, certificates of deposit, and other short-term instruments offered by investment companies, banks, and other financial institutions. Most insurers invest funds from their universal life contracts primarily in short-term investments so they can have the liquidity to meet policyholder demands for cash values. Some other insurers use investment portfolios that are competitive with medium- and long-term investment returns. A key feature of the product is its flexibility. The policyowner can do the following:

- Change the amount of premium periodically

- Discontinue premiums and resume them at a later date without lapsing the policy

- Change the amount of death protection (subject to restrictions)

Universal life was introduced during a period of historically high, double-digit interest rates. Sales illustrations often projected high investment returns for many years into the future, resulting in illustrated cash values that surpassed those of traditional cash value policies. Traditional policy illustrations projected dividends and cash values using average investment returns for a portfolio of securities and mortgages purchased during periods of low, medium, and high interest rates. Consumers were attracted to the high new money rates of the early 1980s, which resulted in universal life growing to a sizable market, with $146.3 billion of face amount in 2000. The share of the market declined when interest rates declined and it increased as the stock market became bearish.

Separation of Elements

Traditional cash value life insurance products do not clearly show the separate effect of their mortality, investment, and expense components. The distinguishing characteristic of universal life contracts is a clear separation of these three elements. This is called unbundlingFeature of universal life that clearly shows the separate effect of mortality, investment, and expense components.. The separation is reported at least annually, by a disclosure statement. The disclosure statementIn universal life, annually reporting of the gross rate of investment return credited to the account, the charge for death protection, expense charges, and the resulting changes in accumulation value and in cash value. shows the following:

- The gross rate of investment return credited to the accountThe advertised rate of return credited to the account is likely to be higher than the true rate of return being earned on the cash value element of the contract. This issue was discussed at length in Chapter 9 "Fundamental Doctrines Affecting Insurance Contracts" regarding vanishing premiums and market conduct.

- The charge for death protection

- Expense charges

- The resulting changes in accumulation value and in cash value

This transparency permits seeing how the policy operates internally, after the fact.

The insurer maintains separate accounting for each policyowner. The account has three income items:

- New premiums paid

- Guaranteed interest credited

- Excess interest credited

The cash outflow items, from a consumer perspective, consist of the following:

- A mortality charge for death protection

- Administrative and marketing expenses

- Withdrawals or loans

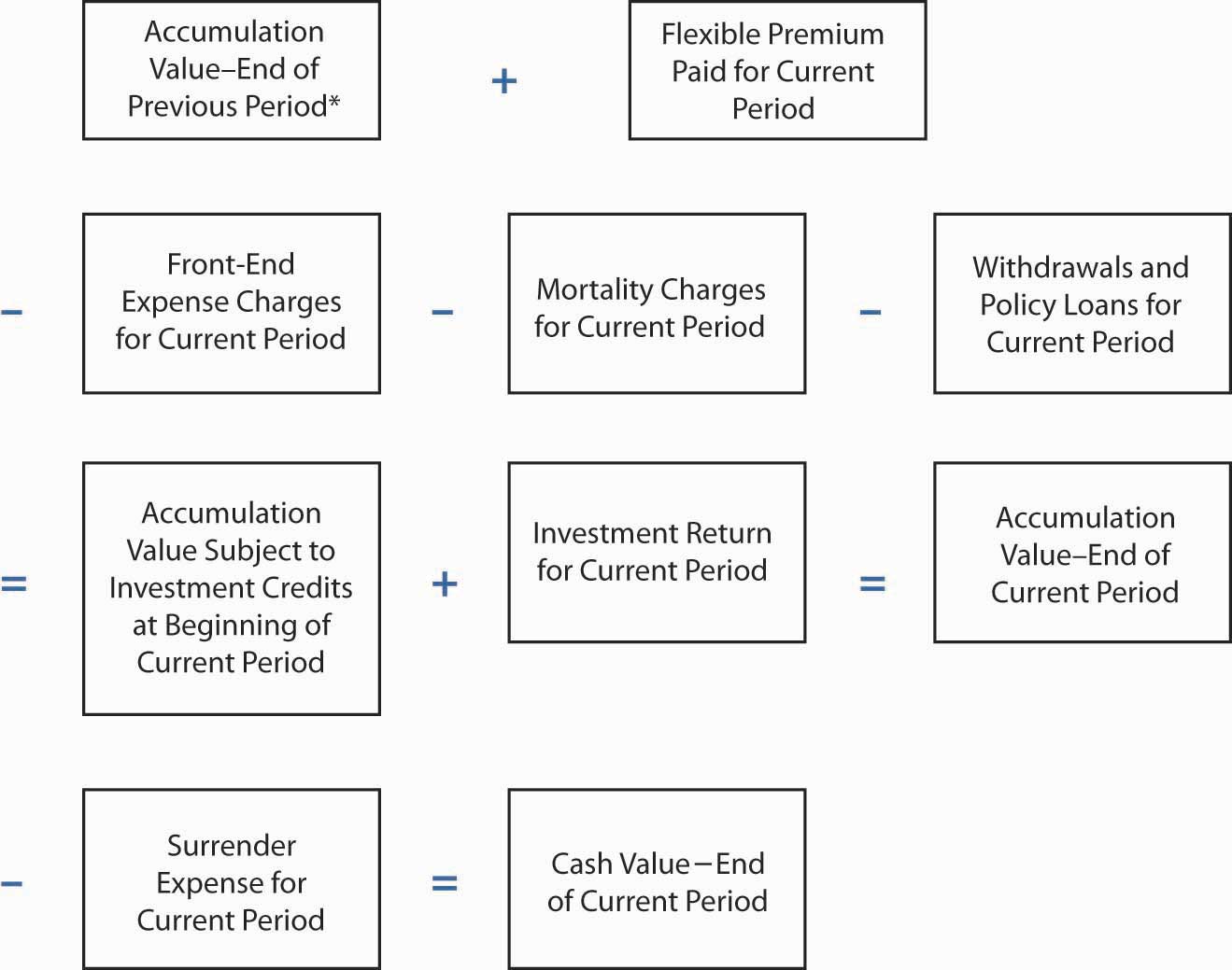

The difference between cash income and outflow in universal life becomes a new contribution to (or deduction from) the accumulation valueThe value of the annuity contract during the accumulation period; consists of premiums plus investment earnings minus expenses. account. Visualize this as the level of liquid in an open container where the three income items flow in at the top and the outflow items are extracted through a spigot at the bottom. Accounting usually occurs on a monthly basis, followed by annual disclosure of the monthly cash flows. The steps in the periodic flow of funds for a universal life policy are shown in Figure 19.5 "Flow of Funds for Universal Life Insurance". The first premium is at least a minimum amount specified by the insurer; subsequent premiums are flexible in amount, even zero if the cash value is large enough to cover the current cost of death protection and any applicable expense charges.

Administrative and marketing expense charges are subtracted each period. Some policies do not make explicit deductions. Instead, they recover their expenses by lowering investment credits or increasing mortality charges (limited by guaranteed maximums). Another periodic deduction is for mortality. The policyowner decides whether withdrawals (that is, partial surrenders of cash values) or policy loans are made. They cannot exceed the current cash value. If the entire cash value is withdrawn, the contract terminates. Withdrawals and loans reduce the death benefit as well as the cash value.

After deductions at the beginning of each accounting period for expenses, mortality, and withdrawals, the accumulation value is increased periodically by the percentage that reflects the insurer’s current investment experience (subject to a guaranteed minimum rate) for the portfolio underlying universal life policies.

The difference between the accumulation value and what can be withdrawn in cash (the cash value) at any point in time is determined by surrender expenses. Surrender expenses and other terms will become clearer as aspects of universal life are discussed in more detail in the next chapter sections.

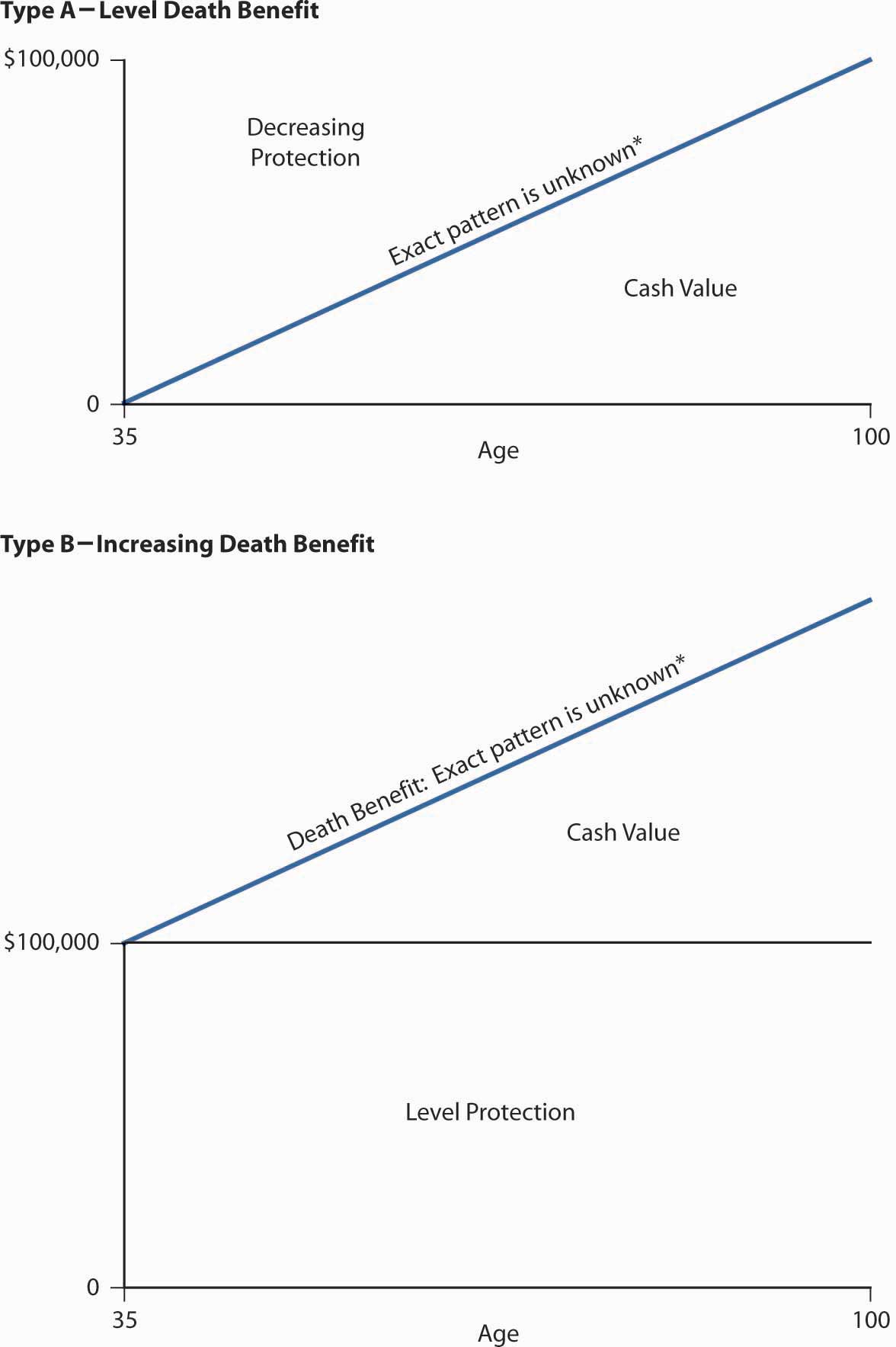

Death Benefit Options

Figure 19.6 "Two Universal Death Benefit Options" shows two death benefit options that are typically available. Type A keeps a level death benefit by making dollar-for-dollar changes in the amount of protection as the investment (cash value account) increases or decreases. This option is expected to produce a pattern of cash values and protection like that of a traditional, ordinary life contract. When a traditional, straight life contract is issued, the policy stipulates exactly what the pattern of cash values will be and guarantees them. In universal life contracts, there are illustrations of cash values for thirty years or so, assuming the following:

- A specified level of premium payments

- A guaranteed minimum investment return

- Guaranteed maximum mortality rates

Another column of this type of illustration shows values based on current investment and mortality experience. Company illustration practices also usually provide a column of accumulation and cash values based on an intermediate investment return (that is, a return between the guaranteed and current rates).

Figure 19.5 Flow of Funds for Universal Life Insurance

* This accumulation value is zero for a new policy.

The type B option is intended to produce an increasing death benefit. The exact amount of increase depends on future nonguaranteed changes in cash value, as described in the discussion of type A policies. The type B alternative is analogous to buying a yearly, renewable level term insurance contract and creating a separate investment account.

With either type, the policyowner may use the contract’s flexibility to change the amount of protection as the needs for insurance change. Like traditional life insurance contracts, additional amounts of protection require evidence of insurability, including good health, to protect the insurer against adverse selection. Decreases in protection are made without evidence of insurability. The insurer simply acknowledges the request for a different death benefit by sending notification of the change. The contract will specify a minimum amount of protection to comply with federal tax guidelines. These guidelines must be met to shelter the contract’s investment earnings (commonly called inside interest buildup) from income taxes.

Figure 19.6 Two Universal Death Benefit Options

* Cash values may decrease and even go to zero, for example, due to low investment returns or inadequate premium payments.

Cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) riders and options to purchase additional insurance are available from most insurers, as you will see at end of this chapter. COLA ridersIncrease the death benefit of universal life annually, consistent with the previous year’s increase in the consumer price index. increase the death benefit annually, consistent with the previous year’s increase in the consumer price index (CPI). Thus, if inflation is 3 percent, a $100,000 type A policy reflects a $103,000 death benefit in the second year. Of course, future mortality charges will reflect the higher amount at risk to the insurer, resulting in higher costs of death protection and lower cash values, unless premiums or investment returns increase concomitantly. Options to purchase additional insurance give the contractual right to purchase stipulated amounts of insurance at specified future ages (generally limited to age forty) and events (e.g., the birth of a child) without evidence of insurability.

Premium Payments

Most universal policies require a minimum premium in the first policy year. In subsequent years, the amount paid is the policyowner’s decision, subject to minimums and maximums set by insurers and influenced by Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rules.

Mortality Charges

Almost all universal life insurance policies specify that mortality charges be levied monthly. The charge for a particular month is determined by multiplying the current mortality rate by the current amount of protection (net amount at risk to the insurer). The current mortality rateIn universal life, can be any amount determined periodically by the insurer as long as the charge does not exceed the guaranteed maximum mortality rate specified in the contract. can be any amount determined periodically by the insurer as long as the charge does not exceed the guaranteed maximum mortality rate specified in the contract. Maximum mortality rates typically are those in the conservative 1980 CSO Mortality Table. Updated mortality tables were adopted in 2006 based on the 2001 CSO Mortality Table, as discussed in “New Mortality Tables” of Chapter 17 "Life Cycle Financial Risks".

The current practice among most insurers is to set current mortality rates below the specified maximums. Mortality charges vary widely among insurers and may change after a policy is issued. Consumers should not, however, choose an insurer solely based on a low mortality charge. Expense charges and investment returns also factor into any determination of a policy’s price. It is also unwise to choose a policy solely on the basis of low expenses or high advertised gross investment returns.

Expense Charges

Insurers levy expense charges to help cover their costs of marketing and administering the policies. The charges can be grouped into front-end expensesIn universal life, expenses applied at the beginning of each month or year consisting of some combination of (1) a percentage of new premiums paid, (2) a small flat dollar amount per month or year, and (3) a larger flat dollar amount in the first policy year. and surrender expensesIn universal life, marketing and administrative expenses applied when policies are terminated. (back-end expenses). Front-end expenses are applied at the beginning of each month or year. They consist of some combination of: (1) a percentage of new premiums paid (e.g., 5 percent, with 2 percent covering premium taxes paid by the insurer to the state); (2) a small flat dollar amount per month or year (e.g., $1.50 per month), and (3) a larger flat dollar amount in the first policy year (e.g., $50). Universal life policies began with high front-end expenses, but the trend has been toward much lower or no front-end expenses due to competition among companies. Those that levy front-end expenses tend to use only a percentage of premium load in both first and renewal policy years. Policies with large front-end loads seldom levy surrender expenses.

As most early issuers of universal policies lowered their front-end charges, they added surrender charges. Whereas front-end expenses reduce values for all insureds, surrender expenses transfer their negative impact to policyowners who terminate their policies. Surrender charges help the insurer recover its heavy front-end underwriting expenses and sales commissions. Questions exist about whether or not they create equity between short-term and persisting policyholders. A few insurers issue universal policies with neither front-end nor surrender charges. These insurers, of course, still incur operating expenses. Some lower operating expenses by distributing their products directly to consumers or through financial planners who charge separate fees to clients. These no-load products still incur marketing expenses for the insurers that must promote (advertise) their products through direct mail, television, and other channels. They plan to recover expenses and make a profit by margins on actual mortality charges (current charges greater than company death claim experience) and margins on investment returns (crediting current interest rates below what the company is earning on its investment portfolio). Thus, even no-load contracts have hidden expense loads. Expense charges of all types, like current mortality rates, vary widely among insurers. Advertised investment returns are likely to vary in a narrower range.

Investment Returns

Insurers reserve the right to change the current rate of return periodically. Some guarantee a new rate for a year; others commit to the new rate only for a month or a quarter.

The indexed investment strategyTies the rate of return on cash values in life insurance to a published index, such as rates on ninety-day U.S. Treasury bills or Moody’s Bond Index. used by some insurers ties the rate of return on cash values to a published index, such as rates on 90-day U.S. Treasury bills or Moody’s Bond Index, rather than leaving it to the insurer’s discretion and its actual investment portfolio returns. This approach also provides a guarantee between 4 and 5 percent.

Some insurers use a new money rate for universal contracts. As explained earlier, the new money rateIn life insurance, credits the cash value account with the return an insurer earns on its latest new investments. approach credits the account with the return an insurer earns on its latest new investments. The practice dictates investment of universal life funds in assets with relatively short maturities in order to match assets with liabilities. When short-term rates are relatively high, such as in the early 1980s, the new money approach produces attractive returns. When short-term returns drop, as they did after the mid-1980s, the approach is not attractive, as noted earlier.

Summary: Features of Universal Life

- In summary, in universal life, we see the following features (see also Table 19.1 "Characteristics of Major Types of Life Insurance Policies"):

- Death benefits: level or increasing

- Cash value: guaranteed minimum cash value plus additional interest when rates are higher than guaranteed

- Premiums: flexible

- Policy loans: yes, but the interest credited to the account is reduced

- Partial withdrawals: allowed

- Surrender charges: yes

Variable Life Insurance

To overcome policyholder fears that inflation will erode life insurance values, variable life insuranceProvides the opportunity to invest funds in the stock market; created to overcome policyholder fears that inflation will erode life insurance values. provides the opportunity to invest funds in the stock market.

The theory of variable life insurance (and variable annuities) is that the prices of the stock and other equities purchased by the insurer for this product will provide insureds with access to any investment vehicle available in the marketplace and will not be limited to fixed-income products. Investments supporting variable life insurance are held in one or more account(s) separate from the general accounts of the insurer. This distinguishes them from investments underlying other life and health insurance contracts.

Each variable life consumer has a choice of investing in a combination of between five and twenty different separate accounts with varying investment objectives and strategies. For example, you might add more short-term stability by placing part of your money in a short-term bond fund while maintaining a significant equity element in one or more common stock funds. Each separate account makes investments in publicly traded securities that have readily determined market values. Market values are needed to determine the current values of cash/accumulation values and death benefits. Cash values vary daily, and death benefits vary daily, monthly, or annually.

Variable life transfers all investment risks to the policyowner. Unlike universal life, for example, which guarantees the fixed-dollar value of your accumulation fund and a minimum return, variable insurance products make no guarantee of either principal or returns. All the investment risk (upside or downside) is yours. Cash values (but not death benefits) can go to zero as a result of adverse investment experience.

How It Works

The Model Variable Life Insurance Regulation, produced by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, sets guidelines that help establish the form of the product. Certain basic characteristics can be identified.

Variable life is, in essence, a whole life product that provides variable amounts of benefit for the entire life. It requires a level premium; therefore, the out-of-pocket contributions do not change with changes in the cost of living. This limits the extent to which death benefits can increase over time because no new amounts of insurance can be financed by defining the premium in constant dollars. All increases in death benefits must come from favorable investment performance.

Contracts specify a minimum death benefit, called the face amount. In one design, this minimum stays level during the life of the contract. Another design uses increasing term insurance to provide automatic increases of 3 percent per year for fourteen years, at which point the minimum face amount becomes level at 150 percent of its original face value. Assuming continuation of premium payments, the face amount can never go below the guaranteed minimum.

Each separate account is, in essence, a different mutual fund. For example, one contract offers five investment accounts: (1) guaranteed interest, (2) money market, (3) a balance of bonds and stocks, (4) conservative common stock, and (5) aggressive common stock. The policyowner could allocate all net premiums (new premiums minus expense and mortality charges) to one account or divide them among any two or more accounts. Currently, approximately 75 percent of separate account assets are in common stocks. Some policies limit the number of changes among the available accounts. For example, some contracts set a limit of four changes per year. Administrative charges may accompany switches among accounts, especially when one exceeds the limit. Because the changes are made inside a life insurance product where investment gains are not subject to income taxes (unless the contract is surrendered), gains at the time of transfer among accounts are not taxable.

It is assumed that investments in the underlying separate accounts will earn a modest compound return, such as 4 percent. This assumed rate of returnIn variable life insurance, generally is a rate necessary to maintain the level of cash values found in a traditional fixed-dollar straight life contract. is generally a rate necessary to maintain the level of cash values found in a traditional fixed-dollar straight life contract. Then, if actual investment returns exceed the assumed rate, (1) cash values increase more than assumed, and (2) these increases are used partly to purchase additional death benefits.

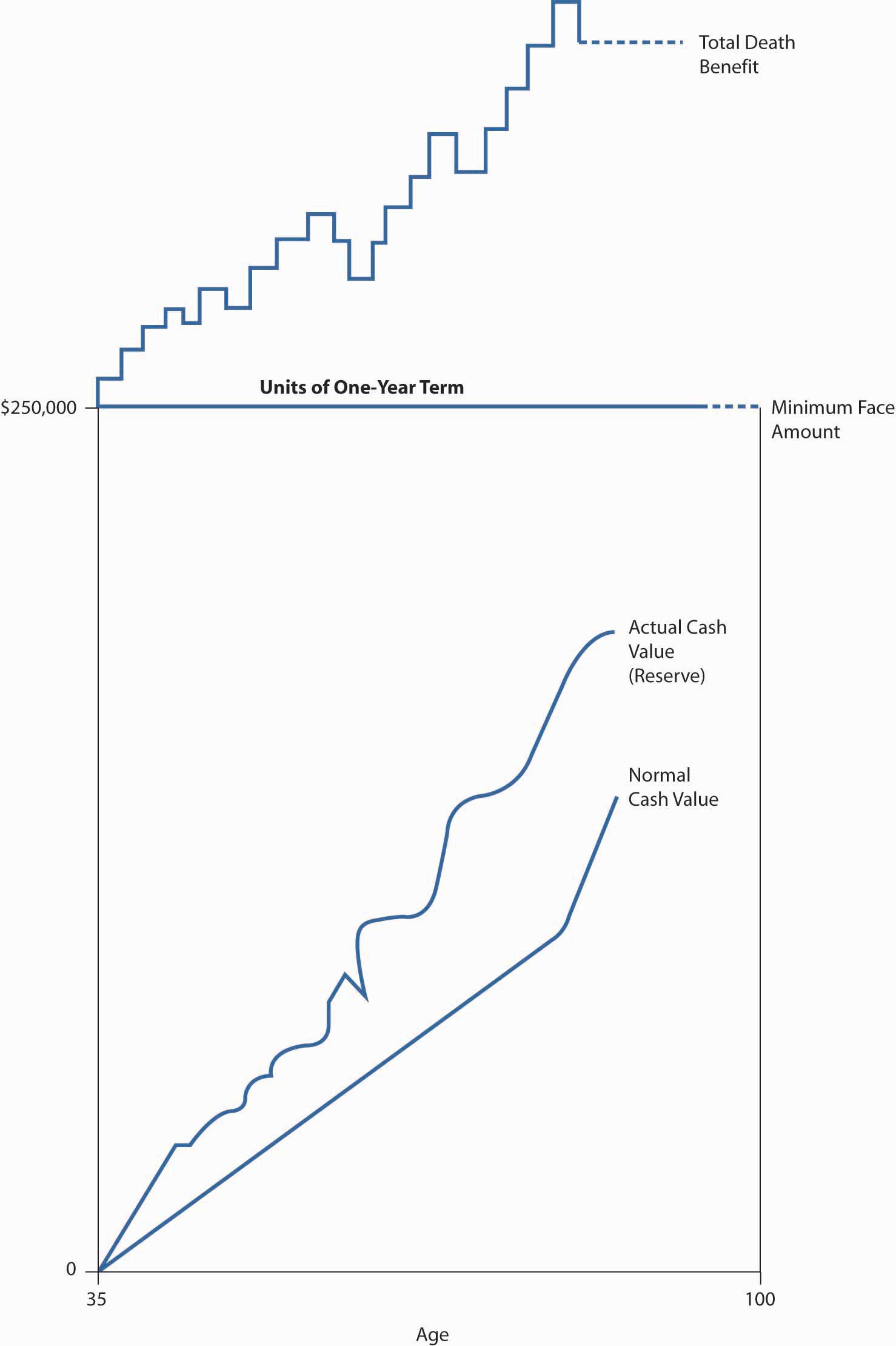

The additional death benefits are usually in the form of term insurance. The amount of term insurance can change (upward or downward) daily, monthly, or yearly, depending on the provisions of the contract. The total death benefit, at a point in time, becomes the amount of traditional straight life insurance that would be supported by a reserve equal to the policy’s current cash value.

If separate account values fall below the assumed rate, (1) the cash value falls, and (2) one-year term elements of death protection are automatically surrendered. The net result is a new death benefit that corresponds to the amount of straight life that could be supported by the new cash value, subject to the minimum death benefit. These variable aspects are what give the contract its name. The nature of variable life insurance, with one-year term additions, is depicted in Figure 19.7 "Hypothetical Values for a Variable Life Insurance Contract".

Policy loans and contract surrenders can be handled by transferring funds out of the separate account. Loans are typically limited to 90 percent of the cash value at the time of the latest loan. Surrenders are equal to the entire cash value minus any applicable surrender charge.

Some variable contracts are issued on a participating basis. Because investment experience is reflected directly in cash values, dividends reflect only unanticipated experience with respect to mortality and operating expenses.

Figure 19.7 Hypothetical Values for a Variable Life Insurance Contract

Note: The relationship depicted between the actual cash value and the total death benefit is approximate. It has not been drawn precisely to scale.

Variable life insurance is technically a security as well as insurance. Therefore, it is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)—which enforces the Investment Company Act of 1940, the Securities Act of 1933, and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934—as well as by state insurance departments. The SEC requires that an applicant be given a prospectusStatement issued by insurers as required by the SEC explaining the risks of variable life and illustrates how the death benefit and cash values would perform if future investment experience results in returns of 0, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 percent. before being asked to sign an application for variable life. The prospectus explains the risks and usually illustrates how the death benefit and cash values would perform if future investment experience results in returns of 0, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 percent. Returns also can be illustrated based on historical experience of the Standard and Poor’s 500 Stock Price Index. Because the product is a security, it can be sold only by agents who register with and pass an investments examination given by the National Association of Security Dealers.

A midrange assumption (e.g., 4 percent) produces a contract that performs exactly like traditional straight life insurance. The 0 percent return would produce the minimum face amount; the cash value would be below normal for a period and go to zero at an advanced age. Because cash values cannot be negative, the policy would continue from the time the cash values reach zero until the death without cash values. At death, the minimum face amount would be paid. The 8 and 12 percent returns would produce cash values that grow much faster than those normal for an ordinary life policy; the total death benefit would continue to grow above the minimum face amount. These examples all assume continuous payment of the fixed annual premium.

Summary: Features of Variable Life

The cash value in a variable life policy fluctuates with the market value of one or more separate accounts. Death benefits, subject to a minimum face amount, vary up or down as the cash value changes. Success in achieving the objective of maintaining a death benefit that keeps pace with inflation depends on the validity of the theory that certain investments are good inflation hedges. All investment risks are borne by the policyowner rather than by the insurer. The issuer of a variable life policy assumes only mortality and expense risks.

In summary, in variable life we see the following features (see also Table 19.1 "Characteristics of Major Types of Life Insurance Policies"):

- Death benefits: guaranteed minimum plus increases from investments

- Cash value: minimum not guaranteed; depends on investment performance

- Premiums: fixed level

- Policy loans: yes

- Partial withdrawals: not allowed

- Surrender charges: yes

Variable Universal Life Insurance

In 1985, variable universal life was marketed for the first time. Variable universal life insuranceCombines the premium and death benefit flexibility of a universal policy design with the investment choices of variable life. combines the premium and death benefit flexibility of a universal policy design with the investment choices of variable life. This policy is also called flexible premium variable life insurance. Some insurers allow all premiums to vary after the first year of the contract. Others specify minimum premiums that would, if paid, continue death protection at least through age sixty-five. Premiums can exceed these minimums. Single-premium policies are also available.

Like the universal life policyowner, the variable universal life policyowner decides periodically whether to decrease death protection (subject to the contract’s minimum face amount) or increase death benefits (subject to evidence of insurability). One design specifies a fixed face amount, like the type A design of universal life (see Figure 19.6 "Two Universal Death Benefit Options"), and allows investment experience to affect only cash values. Another design, like variable life, allows the total amount of protection to increase when cash values exceed their normal level for a straight life contract.

As with variable life, the assets backing variable universal policies are invested in separate accounts. The choices are like those for variable life policies, and the policyowner continues to assume all investment risks. The flow of funds due to expenses, mortality charges, and policy loans for both variable and variable universal work like those in universal policies. The outlook for the sale of variable universal policies is bright because the contract combines the following:

- The premium flexibility of universal life

- The death benefit flexibility of universal life

- Greater investment flexibility than universal life

- The disclosure of universal and variable life

- The ability to withdraw cash values as policy loans without any tax penalties (this is an advantage in comparison to annuities rather than to other types of life insurance)

Separate accounts are not general assets of an insurer. Therefore, they are protected in the event of the insurer’s insolvency. The major drawback of variable universal life, as with variable life, is the transfer of all investment risk to the policyowner.

Summary: Features of Variable Universal Life

In summary, in variable universal life, we see the following features:

- Death benefits: guaranteed minimum plus increases from investments

- Cash value: minimum not guaranteed; depends on investment performance

- Premiums: flexible

- Policy loans: allowed

- Partial withdrawals: allowed

- Surrender charges: yes

Current Assumption Whole Life Insurance