This is “Competing Effectively through Global Marketing, Distribution, and Supply-Chain Management”, chapter 14 from the book Challenges and Opportunities in International Business (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 14 Competing Effectively through Global Marketing, Distribution, and Supply-Chain Management

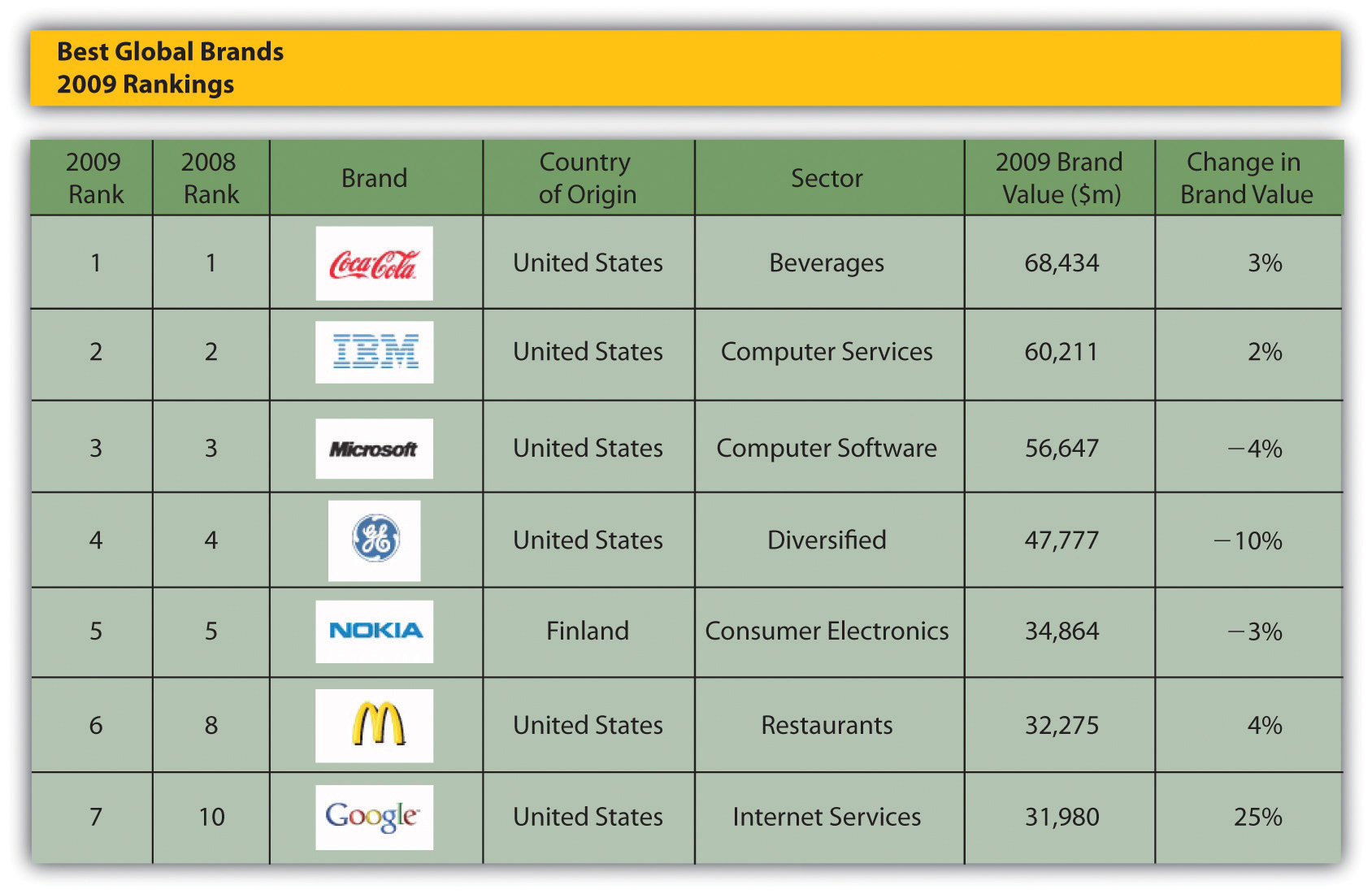

Source: Interbrand

What’s in It for Me?

- What are the fundamentals of global marketing?

- What are the trade-offs between standardized and customized products and promotions?

- What are the fundamentals of distribution?

- How does international distribution differ from purely domestic distribution?

- What are the international aspects of supply-chain management?

In this chapter, you’ll learn the “hows” of global marketing, distribution, and supply-chain management. Specifically, you’ll see how companies decide which products to market internationally, how to source and distribute those products, and how to manage operations for smooth operation throughout the company’s supply chain.

The chapter opens with a case study on Yum! Brands’ entry into China with KFC restaurants. After initial missteps, Yum! Brands and KFC have had great success and are now pondering ways to sustain that success. In Section 14.1 "Fundamentals of Global Marketing", you’ll learn the fundamentals of marketing in an international context. If the world were truly flat, then it would be easy to sell a product or service that is popular in one setting in another country setting with little additional work. However, because the world is not truly flat in terms of culture, administration, geography, and economics (i.e., CAGE), firms must make choices as to how they adapt to or avoid international markets. You’ll see how companies like Starbucks adapt and innovate in different markets, how integrated-circuit maker Intel deals with the difficulties of counterfeit markets, and how entertainment giant Bertelsmann makes decisions in emerging markets. You’ll also get a glimpse of how consumers in BRIC countries (i.e., Brazil, Russia, India, and China) differ and the special challenges of marketing products to countries where incomes are low.

You’ll be following along as companies like Nokia make decisions about whether to adapt products to specific markets. You’ll see the innovations that Procter & Gamble and General Electric create as they develop products for BRIC countries and how these innovations earn them additional benefits back home in developed markets. You’ll learn how to avoid the pitfalls that trapped Ford Motor Company, and you’ll see the entrepreneurial approaches to distribution management that Unilever created. Section 14.4 "Global Sourcing and Distribution" will highlight the difference between outsourcing and offshoring and the advantages and disadvantages they bring. Finally, Section 14.5 "Global Production and Supply-Chain Management" will demonstrate the value of an integrated approach to supply-chain management.

Opening Case: Colonel Sanders Is No Chicken!

Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) was the first American fast-food restaurant to enter China, opening its first outline there in 1987 in Beijing.The Gale Group Inc., “KFC Corporation,” International Directory of Company Histories, accessed December 19, 2010, http://www.answers.com/topic/kfc-corporation. KFC’s US archrival, McDonald’s, didn’t open a restaurant in China until 1990.Jennifer Lawinski, “KFC, Taco Bell a Hit for YUM! in China,” Slashfood, July 15, 2010, accessed December 14, 2010, http://www.slashfood.com/2010/07/15/kfc-taco-bell-a-hit-for-yum-in-china/#ixzz16JzYnIBS. Despite initial marketing mistakes—like its “finger lickin’ good” slogan being mistranslated into Chinese characters that meant “eat your fingers off”—the company grew and thrived.Carlye Adler, “Colonel Sanders’ March on China,” Time, November 17, 2003, accessed December 14, 2010, http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,543845,00.html. Today, KFC has 2,872 restaurants in China, which generate over $2 billion in sales for its parent company, Yum! Brands.“Restaurant Counts: 2009 Q4 Restaurant Units Activity Summary,” Yum! Brands, accessed December 14, 2010, http://www.yum.com/investors/restcounts.asp.

KFC is gaining popularity in the large Chinese market.

Source:© Yum! Brands

The main factor contributing to KFC’s success in China is its localization strategy. Let’s see how KFC did it.

When KFC first entered the Chinese market, Chinese law stipulated that foreign companies could only operate in China if they had a local partner. KFC selected partners who had connections to government, so that it could benefit from their resources and contacts.Karen Cho, “KFC China’s Recipe for Success,” INSEAD, July 1, 2009, accessed December 14, 2010, http://knowledge.insead.edu/KFCinChina090323.cfm?vid=195. KFC learned a lot from its local partners, and once joint ventures were no longer required, KFC chose a leadership team that knew Chinese culture intimately. Rather than sending expatriates to China to lead the expansion, for example, KFC selected people who had “an understanding of China and the Chinese cultural context ‘so deep that it is intuitive,’ to understand the Chinese people’s ‘mixed feelings, of love and hate about the West, to understand Chinese history, language, the influence of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, this is especially important if you are in the consumer goods industry,’” said Warren Liu, former vice president of development at KFC China and author of the book KFC in China: Secret Recipe for Success.John Sexton, “KFC—‘A Foreign Brand with Chinese Characteristics,’” China.org.cn, September 22, 2008, accessed December 14, 2010, http://www.china.org.cn/business/2008-09/22/content_16515747.htm. This leadership team recommended that KFC follow a strategy of localization: offering local Chinese food options on the menu to appeal to local tastes. For example, instead of serving coleslaw, KFC offers bamboo shoots and lotus roots. Likewise, it sells a sandwich in the style that Peking duck is served, simply substituting fried chicken for the duck.“Kentucky Fried China,” MSNBC, January17, 2005, accessed December 14, 2010, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/6833233/ns/business-world_business. The extent of KFC’s product localization is extensive, from preserved Sichuan pickle and shredded pork soup to a Chinese-style porridge called congee for breakfast.Aaron Hotfelder, “Why Does China Love KFC More Than McDonald’s?,” Gadling (blog), June 5, 2010, accessed December 14, 2010, http://www.gadling.com/2010/06/05/why-does-china-love-kfc-more-than-mcdonalds.

KFC’s promotional marketing is similarly steep in Chinese culture. As Yu Cui and Zhang Ting explain, “China is a society with relatively high collectivism, where people have a high sense of identity to the traditional culture and traditional food. Since the family members in China often share the similar value and most Chinese people consider that it is necessary to keep on the wonderful family traditions, such as respecting, loving and supporting the elderly, helping others, friendship between individuals and so on. Thus, many advertisements of KFC in recent years try to reveal the background of common Chinese families.”Yu Cui and Zhang Ting, “American Fast Food in Chinese Market: A Cross-Cultural Perspective—The Case of KFC and McDonald’s” (master’s diss. in international marketing, University of Halmstad, Halmstad, Sweden, 2009), 41, accessed December 14, 2010, http://hh.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:286121/FULLTEXT01.

KFC emphasizes speed and convenience rather than chicken. “Choosing to eat at fast food restaurants like KFC doesn’t necessarily indicate a desire for Western flavors,” said Sun Min, a local government official who eats at KFC because speed and convenience are his top priorities when choosing a place to eat.“Western Fast Food Giants Meet the Challenges of Local Culinary Preferences,” Alibaba, June 9, 2009, accessed December 15, 2010, http://resources.alibaba.com/topic/531563/KFC_s_localization_strategy_in_China_.htm.

Selecting the right place or location for its outlets is also important for convenience, and KFC is opening stores at a pace of nearly one a day in China, to be close to wherever its customers are.Ben Rooney, “China: The New Fast Food Nation,” CNN Money, July 14, 2010, accessed December 15, 2010, http://money.cnn.com/2010/07/13/news/companies/Yum_Brands/index.htm. KFC also developed its distribution system quickly, right from the start, and its parent, Yum! Brands, owns those distribution centers. Owning its own distribution centers lets Yum! Brands grow it restaurants efficiently as it expands into 402 cities in China.“Yum! Execs Discuss China Strategy, Franchising and the Recent Minimum Wage Uproar,” Seeking Alpha, May 6, 2007, accessed December 14, 2010, http://seekingalpha.com/article/34612-yum-execs-discuss-china-strategy-franchising-and-the-recent-minimum- wage-uproar.

For the future, David Novak, CEO of Yum! Brands (which owns Pizza Hut and Taco Bell in addition to KFC), said he envisions eventually having more than twenty thousand restaurants in China. “We’re in the first inning of a nine-inning ball game in China,” Novak told investors in a conference call in February 2010.Samuel Shen, “Kentucky Fried Chicken Banks on China,” New York Times, May 5, 2008, accessed December 14, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/05/business/worldbusiness/05iht-kfc.1.12567957.html?_r=1.

Opening Case Exercises

(AACSB: Ethical Reasoning, Multiculturalism, Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- Do you think that Yum’s other restaurants—Pizza Hut and Taco Bell—would be successful in China? Why or why not? What would help them be more successful?

- What advice would you give KFC about how to continue its growth in China?

- How might KFC’s presence in China help the restaurant in other markets?

14.1 Fundamentals of Global Marketing

Learning Objectives

- Understand the four Ps of marketing and how they differ in international marketing.

- Know how to segment international markets.

- Be able to explain how gray and counterfeit markets can be harmful to companies.

The Four Ps

As we saw in the opening case, KFC has had great success in China after a first failed attempt. Why did KFC try again after its first failure? For the same reason that most companies market their products globally. Specifically, companies expand internationally to reach more customers, gain higher profit opportunities, balance sales across countries in case one country experiences problems, and compete with other brands that are expanding internationally and with global firms in their home markets.

Reaching new consumers is often the main reason for international expansion. The rising standards of living in the developing world, especially BRIC countries (i.e., Brazil, Russia, India, and China) mean billions of new consumers.MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics, “Crossroads of Supply Chain and Strategy Symposium 2008” (symposium, MIT, Cambridge, MA, March 27, 2008). In fact, 80 percent of the world’s population lives in emerging-market countries. Companies based in the mature economies of the West are attracted by the potential for double-digit growth in emerging markets.

What is the best way to reach those international customers? You begin with the core of marketing knowledge—the four PsThe four key elements of marketing—product, price, promotion, and place.—product, price, promotion, and place. While you likely learned this framework in your marketing class, it’s important to recognize how this essential tool will help you think about marketing in the context of international business. In a flat world, the answers to questions about the four Ps are all the same; however, because the world isn’t really that flat, country differences will have important implications for how product, price, promotion, and place play out when an organization takes its offerings across borders.

The first P—productAny physical good or intangible service that is offered for sale.—refers to any physical good or intangible service that’s offered for sale. For example, the product could be physical, like a laser printer, or it could be a service, like printing or photocopying services. The product could also be access to information, such as stock-market reports. Given the differences between countries (e.g., language, culture, laws, and technology standards), a company’s products may need to be adapted to different countries. Some products, like Coca-Cola or Starbucks coffee, need little, if any, modification. But even these companies create product variations to suit local tastes. For example, Starbucks introduced a green tea Frappuccino in China. The new flavor was very successful there. We’ll learn more about product standardization and customization in the next section.

Did You Know?

Innovation at Starbucks

Annie Young-Scrivner, Starbucks’s chief marketing officer, described her company’s plans for innovation and international expansion. “We continue to have very solid plans for China,” Young-Scrivner said. “As we expand outside of the U.S. and get more depth in [international] markets, we’re finding lots of best practices and innovation that we can bring back. There are so many examples of creativity, like flat white [a milk and espresso beverage] in the U.K., black sesame [and] green tea Frappuccino in China. Green tea Frappuccino came from an international market and we launched it here. The local relevance became a tipping point for innovation in other markets for the brand.”Emily Bryson York, “The Global CMO Interview: Annie Young-Scrivner, Starbucks: ‘Local Relevance Became a Tipping Point for Innovation in Other Markets,’” Advertising Age, June 14, 2010, accessed November 4, 2010, http://adage.com/cmostrategy/article?article_id=144390.

The second P—priceThe amount of money that the consumer pays for the product.—is the amount of money that the consumer pays for the product. Pricing can take different forms. For example, pricing can be by item (e.g., a can of corn), by volume (e.g., gasoline), by subscription (e.g., monthly cable service), by usage (e.g., cell-phone minutes), or by performance (e.g., paying more for overnight delivery versus two-day delivery).

Let’s spend a little more time on price, because pricing has even more nuances when applied to international products. For example, emerging-market countries often have a less-developed financial system and limited credit available to local consumers and businesses. Some of the biggest challenges in selling to emerging markets involve making the product affordable. In Brazil, 26 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. However, companies have devised ways to help even the poorest consumers afford products. Let’s see how Casas Bahia has succeeded in selling to the bottom-of-the-pyramid (BOP) consumers in Brazil.

Did You Know?

Casas Bahia—Selling to BOP Consumers

Some consumers in developing countries are very poor. Often called the bottom of the pyramid (BOP) on income scales, they are the four billion people who live on less than $2 a day. Would you market products to these people? Surprisingly, the answer may be yes in many instances. According to C. K. Prahalad, BOP consumers are a viable market segment to target.C. K. Prahalad, The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wharton School Publishing, 2004). The key is having the right market mix of product, price, promotion, and place. Let’s see how it works.

Casas Bahia is a retailer in Brazil that sells appliances and furniture. It successfully sells to the BOP. In fact, 45 percent of its appliance and furniture products are sold to BOP consumers. First, consider product. You might think that a refrigerator is a luxury item for these consumers. In a tropical country like Brazil, however, a refrigerator becomes more of a necessity. Second, price: obviously, keeping costs low is key. Casas Bahia does this by buying products in huge volumes to get huge discounts. It has built large warehouses capable of storing much more inventory than a typical retailer would, in order to handle the large volumes. But low prices alone are not enough, as Walmart learned in its failed expansion into Brazil. Indeed, 70 percent of Casas Bahia customers have no formal or consistent income. How are these customers able to pay for their purchases? Casas Bahia helps them by giving them a passbook—similar to a credit card but with important differences. First, Casas Bahia hires credit analysts and trains them extensively, so that they can accurately assess how much a customer can afford to pay. These credit analysts help steer a customer away from products that may be too expensive for them and instead suggest a more modest model. Second, unlike credit-card statements that come in the mail and are easy to ignore, customers must make passbook payments directly inside the Casas Bahia store. This direct approach builds a personal relationship between the customer and the friendly store employees. Rates of default on passbooks are much lower than they are on credit cards. To recap, many of Casas Bahia’s products are seen as more of a necessity than a luxury. Low prices coupled with credit assessment and friendly employees encourage monthly payments. Selling in retail stores (place) reduces the need for external promotions, because customers return monthly to make payments, which gives Casas Bahia an opportunity to sell them additional products.

The third P—promotionAll the activities that inform and encourage consumers to buy a given product, including advertising (whether print, radio, television, online, billboard, poster, or mobile), coupons, rebates, and personal sales.—refers to all the activities that inform and encourage consumers to buy a given product.Michael Solomon, Lisa Duke Cornell, and Amit Nizan, Launch! Advertising and Promotion in Real Time (Nyack, NY: Flat World Knowledge, 2009). Promotions include advertising (whether print, broadcast radio, television, online, billboard, poster, or mobile), coupons, rebates, and personal sales. Like products, promotions are often customized to a country to appeal to local sensibilities. One obvious mistake to avoid is a language translation that misses the nuances of native speakers. For example, a straight translation of Clairol’s “Mist Stick” curling iron into German misses the nuance that “mist” in German is slang for manure. Likewise, Coors’ “turn it loose” slogan, when translated into Spanish, is interpreted by some locals as “suffer from diarrhea.”Richard P. Carpenter, “What They Meant to Say Was…,” Boston Globe, August 2, 1998, M5. Less obvious, but important to know, are the different countries’ regulations affecting advertising. For example, as discussed in Chapter 8 "International Expansion and Global Market Opportunity Assessment", Section 8.2 "PESTEL, Globalization, and Importing", regulations in Germany prohibited discounts, free gifts, or money-back guarantees with purchase. When US clothier Lands’ End expanded into Germany, it was taken to court for its guarantee that “If you’re not satisfied with any item, simply return it to us at any time for an exchange or refund of its purchase price.” Only recently have these German laws been repealed to bring them in line with European Union laws.Jan Peter Heidenreich, “The New German Act against Unfair Competition,” German Law Archive, accessed August 9, 2010, http://www.iuscomp.org/gla/literature/heidenreich.htm#D3c.

The final P—placeThe location at which the company offers its products for sale.—refers to the location at which a company offers its products for sale. The place could be a small kiosk in a village, a store in town, or an online website. Place poses a particular challenge when selling internationally. Many of the things we take for granted in the United States—national retailers, grocery stores, and extensive railways and roadways to reach them—aren’t prevalent everywhere. Section 14.4 "Global Sourcing and Distribution" discusses how to overcome these challenges.

Products reach consumers through a channel of distributionThe series of firms or individuals who facilitate the movement of the product from the producer to the final consumer., which is a series of firms or individuals who facilitate the movement of the product from the producer to the final consumer. The shortest channel, called the direct channelThe shortest channel of distribution, consisting of just the producer and the end consumer. The consumer buys the product directly from the producer., consists of just the producer and the consumer. In this case, the consumer buys directly from the producer, such as when you buy an apple from a local farmer. An indirect channelContains one or more intermediaries between the consumer and the producer. These intermediaries can include distributors, wholesalers, agents, brokers, retailers, international freight forwarders, and trading companies., in contrast, contains one or more intermediaries between the consumer and the producer. These intermediaries include distributors, wholesalers, agents, brokers, and retailers. In international business, the number of intermediaries can expand due to the regulations affecting import and export across national boundaries. Agents, brokers, international freight forwarders, and trading companies may get involved. Then, once a company’s product is in the foreign country, that country may have its own wholesalers who get involved. The firm must pay all these intermediaries for their services, which increases the cost of the product. Firms must raise prices or accept lower margins when confronting these added channel costs.

Even when sales are direct, as with Internet sales, place differences can affect marketing. For example, as mentioned previously, laws in Germany prohibit retailer Lands’ End from advertising its unconditional money-back guarantee because returns are allowed only up to fourteen days.Charles W. Lamb, Joseph F. Hair Jr., and Carl McDaniel, Essentials of Marketing (Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning, 2009), 131.

Ethics in Action

The Case of International Marketing

Major international marketing ethical problems derived from applied research are presented with their short definitions as follows:

- Traditional Small Scale Bribery—involves the payment of small sums of money, typically to a foreign official in exchange for him/her violating some official duty or responsibility or to speed routine government actions (grease payments, kickbacks).

- Large Scale Bribery—a relatively large payment intended to allow a violation of the law or designed to influence policy directly or indirectly (e.g., political contribution).

- Gifts/Favors/Entertainment—includes a range of items such as: lavish physical gifts, call girls, opportunities for personal travel at the company’s expense, gifts received after the completion of transaction and other extravagant expensive entertainment.

- Pricing—includes unfair differential pricing, questionable invoicing—where the buyer requests a written invoice showing a price other than the actual price paid, pricing to force out local competition, dumping products at prices well below that in the home country, pricing practices that are illegal in the home country but legal in host country (e.g., price fixing agreements).

- Products/Technology—includes products and technology that are banned for use in the home country but permitted in the host country and/or appear unsuitable or inappropriate for use by the people of the host country.

- Tax Evasion Practices—used specifically to evade tax such as transfer pricing (i.e., where prices paid between affiliates and/or parent company adjusted to affect profit allocation) including the use of tax havens, where any profit made is in low tax jurisdiction, adjusted interest payments on intra-firm loans, questionable management and service fees charged between affiliates and /or the parent company.

- Illegal/Immoral Activities in the Host Country—practices such as: polluting the environment, maintaining unsafe working conditions; product/technology copying where protection of patents, trademarks or copyrights has not been enforced and short-weighting overseas shipments so as to charge a country a phantom weight.

- Questionable Commissions to Channel Members—unreasonably large commissions of fees paid to channel members, such as sales agents, middlemen, consultants, dealers and importers.Recep Yücel, Halil Elibol, and Osman Dagdelen, “Globalization and International Marketing Ethics Problems,” International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, no. 26 (2009): 100–101, accessed October 22, 2010, http://www.eurojournals.com/irjfe_26_08.pdf.

- Cultural Differences—between cultures involving potential misunderstandings related to the traditional requirements of the exchange process (e.g., transactions) may be regarded by one culture as bribes but be acceptable business practices in another culture. These practices include: gifts, monetary payments, favors, entertainment and political contributions.

- Involvement in Political Affairs—related to the combination of marketing activities and politics including the following: the exertion of political influence by multinationals, engaging in marketing activities when either home or host countries are at war and illegal technology transfers.

The Marketing Mix

The four Ps together form the marketing mixA combination of the four Ps (product, price, promotion, and place) that can be customized for different countries.. Because the four Ps affect each other, marketers look at the mix of product, price, promotion, and place. They fine-tune and adjust each element to meet the needs of the market and to create the best outcome for the company. Promotion has an impact on the other Ps because a product’s price, for example, may be lowered during a promotional event. Likewise, holding a special promotional event like a two-for-one deal on a product impacts place, because the company must ensure that it supplies stores with enough product to meet the anticipated demand. Finally, the promotion might affect the product’s packaging, such as bundling a shampoo and conditioner together.

A company’s marketing mix will often be different for different countries based on

- a country’s culture and local preferences,

- a country’s economic level,

- what a country’s consumers can afford, and

- a country’s distribution channels and media.

Market Segmentation

Market segmentationThe process of dividing a larger market into smaller markets that share a common characteristic, such as age, gender, income level, or lifestyle. is the process of dividing a larger market into smaller markets that share a common characteristic. The characteristics might be demographics, such as segments divided by age groups (e.g., eighteen to twenty-four year-olds), genders, or household incomes. Segmentation can also be done on the basis of geographic location or by lifestyle (e.g., new moms of different ages might have more in common with each other than they have with identically aged nonmothers.) The purpose of segmentation is to give the company a concrete vision of its customers, so that it can better understand how to market to that customer. Segmentation helps companies target their marketing efforts more effectively.

For example, geographic segmentation is important for language differences. Sometimes, the segmentation must be done even more granularly than at the country level. Some parts of Mexico, for instance, don’t use Spanish as the primary language. Because of this, Walmart Mexico’s stores in Juchitán conduct business in the local Zapotec tongue. Its female employees wear traditional skirts, and the morning company cheer is in Zapotec.“Supply Chain Strategies in Emerging Markets” (roundtable discussion at the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics, MIT, Cambridge, MA, March 7, 2007).

Each country may have its own cultural groups that divide the country or transcend national boundaries. For example, the northern coast of Colombia is culturally more similar to the Caribbean than it is to the interior of its own country because the Andes Mountains split the country into two regions: east and west. Historically, these regions had been cut off from each other.

Understanding Your Target Customers

Foreign markets are not just copies of US markets; they require products suitable to the local population. Although European and developed country markets are more similar to the United States, emerging markets like the BRIC countries have important differences. Products must meet local needs in terms of cost, quality, performance, and features and, in order to be successful, a company must be aware of the interplay between these factors. Let’s look at consumers in emerging countries to get a feel for these differences.

Rising Middle Class

The number of middle-class people in emerging countries has been growing, partly because of Western companies hiring low-cost labor (directly or through outsourcing agreements) in these regions. Providing jobs in these countries has improved household incomes. These fast-rising incomes, especially in urban areas, create vast new pools of disposable income. Eight of the ten largest cities in the world are in emerging markets. Their populations are young, and they’re just beginning to adopt the full range of consumer goods found in the developed world.

In some cases, these middle-class consumers will buy more expensive branded goods, if the brands resonate with the interests of the local crowd. Consider the relative sales ratio of $60 Nike basketball shoes versus $120 Yao Ming–branded Nike basketball shoes. In the United States, sales might be 20 percent for the higher priced shoe. In mainland China, it might be 5 percent for the Yao Ming shoe due to cost; but in more prosperous Hong Kong, the sales might be 50 percent for the shoes.“Supply Chain Strategies in Emerging Markets” (roundtable discussion at the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics, MIT, Cambridge, MA, March 7, 2007). Middle-class populations are reading about Western goods and want branded items, but pricing can be an issue depending on the local level of affluence.

Millionaires Are Everywhere

Just because the average income is much lower in emerging markets doesn’t mean that no one can afford high-end luxury goods. Some automobile manufacturers, for example, track the number of millionaires in the country as an indicator of the very affluent segment. By recent estimates, China has approximately 477,000 millionaires,“Number of Millionaires Grows in China,” Digital Journal, June 24, 2010, accessed November 25, 2010, http://www.digitaljournal.com/article/293790. Brazil has approximately 143,000,“World Now Has 10 Million Millionaires,” MSN Money, June 25, 2008, accessed November 25, 2010, http://articles.moneycentral.msn.com/Investing/Extra/WorldNowHasTenMillionMillionaires.aspx. Russia has approximately 136,000,“World Now Has 10 Million Millionaires,” MSN Money, June 25, 2008, accessed November 25, 2010, http://articles.moneycentral.msn.com/Investing/Extra/WorldNowHasTenMillionMillionaires.aspx. and India has approximately 126,000.“Asian Millionaires Overtake Europeans in World Wealth Game,” Hindustan Times, June 23, 2010, accessed November 25, 2010, http://www.hindustantimes.com/Asian-millionaires-overtake-Europeans-in-world-wealth-game/Article1-562154.aspx. These very high net-worth individuals explicitly want the same products that are sold in the West, not down-market versions. Specific cities in emerging-market countries may have a concentration of affluent consumers. In Monterrey, Mexico, for example, the costs of consumer goods are comparable to those of New York City.

Emerging Markets for Business Customers

Business-to-business (B2B) opportunities also abound, as emerging-market businesses grow to serve export or internal markets. Just as with consumers, businesses in emerging markets are different from developed markets. For example, companies in emerging markets may be smaller and less sophisticated and may have lower budgets than their Western counterparts. They may lack the level of automation and information technology that prevails in the developed world. This is especially true in the retail industry. Many developing countries have a predominance of small mom-and-pop stores.

Global Market Research

Global market research includes understanding the market’s culture and social trends, because these factors impact which products consumers will like and which advertising appeals will resonate with them.

Some of the same techniques of market research used in the United States can be applied internationally. For example, Procter & Gamble (P&G) uses a variety of focus-group testing and in-home research to understand why people buy the products they buy. P&G researchers watch how consumers use products and ask about what features they might want in the future. The company has learned from past experience that just because a product sells well in one market doesn’t imply that it will sell well in another market. For example, although Bounty paper towels sell well in the United States, the European launch of Bounty paper towels did well in only two of twelve markets. Why? P&G quickly learned that Germans found the entire concept of paper towels to be too wasteful and, therefore, didn’t buy them.

Dealing with Gray and Counterfeit Markets

The gray marketCommerce areas where, because of price differences across countries, consumers are able to cross international borders to legally purchase products at lower prices than in their home country. exists because of price discrepancies between different markets. For example, consumer packaged-goods companies may price their products higher in Austria than in the neighboring Czech Republic due to the Austrian citizens’ higher income levels. As a result, Austrians might order their goods from Czech retailers and simply drive over the border to pick up the products. The goods in the Czech stores are legitimate and authentic, but the existence of this gray-market activity hurts the producer and their channel partners (e.g., distributors and retailers) in the higher-priced country.

In contrast to gray markets, which are legitimate but—legally—in a gray area, counterfeit marketsCommerce areas where vendors purposely deceive buyers by altering products and then selling them as branded products at a bargain cost. purposely deceive the buyer. For example, counterfeiters slightly alter the Sony logo to Bony in a way that makes it hard to distinguish without careful inspection.

Counterfeit markets hurt companies that have invested in building intellectual assets such as unique product designs, technological developments, costly media content, and carefully crafted brands. Together, these intellectual assets represent an investment of millions or billions of dollars. If a company’s product, technology, or brand is counterfeited, both the company’s reputation and financial security suffers. All of its channel partners (i.e., distributors, retailers, and licensing partners) are affected as well. For example, an executive traveling in Hong Kong saw unique styles of Nike shoes. When he asked about them, he was told the shoes were only available in size nine. This fact led him to realize that the shoes were probably prototype samples from a local factory that had been smuggled out of the factory to be sold. Some industries have tried to limit the scope of the counterfeiting and copying of DVDs through regionalized encoding, but even this is too easy to circumvent. That’s why musical and entertainment giant Bertelsmann avoids expansion into emerging-market countries that have lax enforcement of intellectual property rights.

Counterfeiters may also tamper with branded products. For example, Intel processor chips vary in price based on their processing speed: the higher the speed, the higher the price of the chip. Counterfeiters buy (or steal) low-end chips, repaint a few numbers on them, and then sell them as high-end chips. The high-end chips sell for $100 or $200 more than the low-end chips. Customers looking for a bargain may unwittingly buy these chips. For Intel, these remarked chips not only cannibalize sales of the higher-margin, high-performance chips, but they also create higher warranty costs because customers turn to Intel when these chips fail. The counterfeiting can also damage the brand’s reputation. To defeat counterfeiters, Intel implemented a long list of product-security measures. It replaced removable painted numbers with more-permanent, laser-etched numbers; developed retail packages with holograms and other hard-to-copy markings; and created software to detect any mismatch between the chip’s internal rating and operating speed.

Strategically, Intel executives debated whether to even use the Intel name on products at the low end of the spectrum that were sold in emerging markets. Not using the Intel name would prevent the low-priced goods from re-entering Western markets. The downside of that strategy, however, is less brand recognition in the developing country.

Key Takeaways

- The fundamentals of global marketing begin with the core of marketing knowledge, the four Ps. The four Ps refer to product, price, promotion, and place. When put together, the four Ps form the marketing mix.

- One or more of the four Ps can differ from country to country. For example, the product can differ from country to country if a company chooses to adapt its product to local tastes or to create a new product specifically for local tastes. Thus, Starbucks introduced a green tea Frappuccino in China.

- The second P, price, refers to the amount of money that the consumer pays for the product. Price represents a special challenge when companies sell to emerging markets because consumers’ income levels in these countries are much lower than in developed countries. In addition, the channel of distribution often gets longer when companies sell to international markets. Rather than a direct channel in which a company sells directly to a consumer, intermediaries (i.e., distributors, wholesalers, agents, brokers retailers, international freight forwarders, and trading companies) between the consumer and the producer often characterize the international-market distribution chain. Companies must pay each of these intermediaries, which increases the cost of the product.

- The third P, promotion, refers to the activities that inform and encourage consumers to buy a given product. Companies often customize these promotions to use images and wording that resonate with local markets.

- The final P, place, refers to where a company offers its products for sale. Many emerging countries may lack national retail chains, which means that companies may need to sell their products through a much more fragmented system of small storefronts or kiosks.

- Market segmentation refers to the process of dividing a larger market into smaller markets that share a common characteristic, such as age or lifestyle. It’s important to note that not all citizens of a given country can be marketed to uniformly, because besides demographic differences there may be regional differences within each country as well.

- Price discrepancies between markets can cause the development of gray markets. These price discrepancies are hard to avoid because income levels differ in different countries. Companies want to charge prices that locals in different countries can afford. The result, however, is that consumers in wealthier countries may buy the product in a less-affluent country for a cheaper price. Counterfeit markets deceive customers into buying what they think is a branded product at a bargain price.

Exercises

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- Why might a company’s marketing mix be different for different countries?

- What problems can gray or counterfeit markets cause for companies?

- What are some characteristics of emerging-market customers?

- Explain some ways to segment international markets.

- Name the four Ps and how they might differ in international marketing.

14.2 Critical Decision Points in Global Marketing

Learning Objectives

- Understand the advantages and disadvantages of global branding.

- Know the trade-offs of centralized versus decentralized marketing decision making.

- Identify the special challenges of branding decisions in emerging markets.

Global Branding

A global brandThe brand name of a product that has worldwide recognition. Some of the most recognized brands in the world include Coca-Cola, IBM, GE, and McDonald’s. is the brand name of a product that has worldwide recognition. Indeed, the world does become flatter to the extent a brand is recognized, accepted, and trusted across borders. Some of the most-recognized brands in the world include Coca-Cola, IBM, Microsoft, GE, Nokia, McDonald’s, Google, Toyota, Intel, and Disney.“Best Global Brands Report 2010,” Interbrand, accessed October 22, 2010, http://issuu.com/interbrand/docs/bgb_report_us_version?mode=a_p.

Companies invest a lot in building their brand recognition and reputation because a brand name signals trust. “Trust is what drives profit margin and share price,” says Larry Light, CEO of Arcature brand consultancy and a veteran of McDonald’s and BBDO Worldwide and Bates Worldwide advertising agencies. “It is what consumers are looking for and what they share with one another.”David Kiley and Burt Helm, “The Great Trust Offensive,” BusinessWeek, September 17, 2009, accessed November 4, 2010, http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/09_39/b4148038492933.htm.

The advantages of creating a global brand are economies of scale in production and packaging, which lower marketing costs while leveraging power and scope. The disadvantages, however, are that consumer needs differ across countries, as do legal and competitive environments. So while global branding, and consumer acceptance of such, is a flattener, significant country differences remain even when a firm has a strong global brand. Companies may decide to follow a global-brand strategy but also make adjustments to their communications strategy and marketing mix locally based on local needs.

The decision companies face is whether they should market one single brand around the world or multiple brands. Coca-Cola uses the Coke name on its cola products around the world but markets its water under the Dasani brand. Nestlé uses a local branding strategy for its 7,000 brands but also promotes the Nestlé corporate brand globally.

Acer’s Multiple-Brand Strategy

PC maker Acer sells its personal computers under four different brands. Using a multibrand strategy is a good choice when a country has a strong, positive association with a particular brand. For example, when Taiwan-based Acer bought US PC-maker Gateway, Acer kept the Gateway brand to use in the United States for midtier PCs. In Europe, however, Acer uses the Packard Bell brand. Acer also has two other brands, which are segmented by price. Acer’s eMachines brand is for the lower-end consumer who is most focused on price, whereas the Acer brand is reserved for the highest-quality products aimed at technophiles. This multibrand strategy also helps Acer’s distribution. As Acer’s chief marketing officer, Gianpiero Morbello, says, “It’s difficult to get a retailer to place 50 percent of his space with one brand. It’s easier to split that same space with three brands.”Bruce Einhorn and Tim Culpan, “With Dell in the Dust, Acer Chases HP,” BusinessWeek, March 8, 2010, 58–59.

Global Brand Web Strategy

Companies that are promoting their global brands successfully on the web include Google, Philips, Skype, Ericsson, Hewlett-Packard, and Cisco Systems. These companies are mindful of the cultural and language differences across countries. They have created websites in local languages and are using images and content specific to each country. At the same time, however, each country website has the same look and feel of the main corporate website to preserve the overall brand.Chanin Ballance, “Speaking Their Language: How to Localize Your Message for Global Customers,” Marketing Profs, March 24, 2009, accessed November 4, 2010, http://www.marketingprofs.com/9/speaking-their-language-localize-message-global-customers-ballance.asp.

Planning a Brand Strategy for Emerging Markets

Entering an emerging market with a developed-country brand poses an extra challenge. As noted in Section 14.1 "Fundamentals of Global Marketing", income levels in emerging markets are lower, so companies tend to price their products as inexpensively as possible. This low-cost strategy may have consequences for the company’s brand, however. For example, if a company introduces its brand as a “premium” product despite having a lower price, how will it introduce and differentiate its true “premium” brand later as consumers’ incomes rise?

Branding Issues: How Low Can You Go?

Many emerging markets call for lower-cost goods. But how low can a company go on quality and performance without damaging the company’s brand? The challenge is to balance maintaining a global reputation for quality while serving local markets at lower cost points.

One way to resolve the challenge is to offer the product at quality levels that are the best in that country even though they would be somewhat below developed-country standards. This is the tactic Walmart has successfully used in Mexico. Walmart’s flooring, lighting, and air conditioning make its Mexican stores better than any other local stores even if they might seem Spartan to US consumers.

Walmart stores in Mexico attract the country’s growing middle-class consumers.

© 2011, Walmart Inc.

Centralized versus Decentralized Marketing Decisions

Who has the authority to make marketing decisions? In a centralized-marketing organizational structureThe home-country headquarters retains decision-making power for marketing in all countries., the home-country headquarters retains decision-making power. In a decentralized-marketing organizational structureLocal regional headquarters have the power to make marketing decisions affecting their region., the regions are able to make decisions without headquarters’ approval. The advantage of the centralized structure is speed, consistency, and economies of scale that can save costs (such as through global-marketing campaigns). The disadvantages are that the marketing isn’t tied to local knowledge and doesn’t reflect local tastes, so sales aren’t optimized to appeal to regional differences.

Key Takeaways

- One of the key decisions that must be made when marketing internationally is how to set up the structure of the marketing organization in the company—centralized or decentralized. In a centralized structure, the home-country headquarters makes the decisions, which can save costs and bring consistency to marketing campaigns. In a decentralized organizational structure, the regions are able to make decisions autonomously, which enables regions to tailor their marketing to local sensibilities.

- Another decision concerns whether to pursue a single global-brand strategy or a multiple-brand strategy. A global brand is the brand name of a product that has worldwide recognition, such as Coca-Cola or IBM. Global brands bring economies of scale and marketing power. Multiple brands, however, may resonate more with specific markets, especially if a company merges with or acquires a local brand that is well respected in that region. The purpose of brands is to signal trust. In some cases, consumers may trust a familiar local brand more than a foreign global brand.

- Finally, companies need to plan a brand strategy for emerging markets, where products have to be sold at lower price points, which could hurt a premium brand reputation.

Exercises

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- What are the benefits of a centralized-marketing organization?

- When might a company prefer to make decentralized-marketing decisions?

- List the advantages of a global-brand strategy.

- Discuss the advantages of a multibrand strategy.

- How can a company use the web to promote a global brand while at the same time localizing it?

14.3 Standardized or Customized Products

Learning Objectives

- Understand the trade-offs between standardized versus customized products.

- Know the influence of the country-of-origin effect.

- Comprehend the benefits of reverse innovation.

Straight Product Extension

Companies deciding to market their products in different countries typically have a choice of three common strategies to pursue. The first is the straight product extensionTaking the company’s current products and selling them in other countries without making changes to the product.. This means taking the company’s current products and selling them in other countries without making changes to the product. The advantages of this strategy are that the company doesn’t need to invest in new research, development, or manufacturing. Changes may be made in packaging and labeling, but these are driven by local regulatory requirements. The disadvantages, however, are that its products may not be well suited to local needs and that the products may be more costly due to higher manufacturing and labor costs in the United States.

Product Adaptation

The second strategy is product adaptationThe company strategy of modifying an existing product in a way that makes it better fit local needs. and refers to modifying the company’s existing product in a way that makes it fit better with local needs. For example, when Procter & Gamble (P&G) introduced Tide laundry detergent in emerging markets like India, it changed the formulation to remove softeners. The reformulated Tide cost less than the original Tide. This change was important because price was an important factor in India where income levels were lower. Indian consumers were more able to afford the reformulated Tide.

Another way to localize a product is through packaging. Locally appropriate packaging doesn’t just mean using the country’s language. It also means creating packaging sizes that suit the country. For example, a company wanting to make its products more economical to less-wealthy countries may be tempted to sell larger, economy-sized packaging. But emerging-market consumers often prefer smaller package sizes, even if that increases the cost-per-use. They tend to buy sachets of shampoo rather than economy-size bottles. These smaller sizes are also easier to transport to local villages or to store in smaller-sized homes.

Mobile-phone maker Nokia went a step further in localizing its phones to different markets. The company uses local designers to create mobile-phone handset models that are specifically appropriate for each country. For example, the handsets designed in India are dust resistant and have a built-in flashlight. The models designed in China have a touchscreen, stylus, and Chinese character recognition.

Nokia phones are designed to meet the needs of local consumers.

© 2011, Nokia Inc.

Local designers are more likely to understand the needs of the local population than headquarters-located designers do.

The examples of Tide and Nokia show how companies can create a version of their existing product tailored to specific countries.

Product Invention: P&G Diapers

The third strategy, product inventionCreating an entirely new product for a given local market. In this strategy, companies go back to the drawing board and rethink how best to design a product for a specific country or region., is creating an entirely new product for the target market. In this strategy, companies go back to the drawing board and rethink how best to design a product for that country. You were introduced to this idea in Chapter 13 "Harnessing the Engine of Global Innovation".

The first step in inventing a product for a new country market is to understand the key product characteristics needed to succeed in that market. For example, when P&G wanted to sell diapers in BRIC countries (i.e., Brazil, Russia, India, and China), it started from square one. Rather than merely modifying the existing design, P&G engaged local knowledge and reconsidered all the key features of the design in the context of the needs of the emerging markets.

A major issue was price. To make the diaper affordable, P&G settled on an aggressive price target—each diaper should cost as much as one egg. But the company also wanted a diaper that could uphold the P&G brand name. At first, the designers thought that the lower-cost product needed to do everything that the current developed-world product did. But further discussions refined and narrowed the definition so that P&G could meet the cost target without damaging the brand.

P&G designers debated features such as absorbency, color, fit, and packaging to find a design that was acceptable on cost targets, acceptable to emerging-market consumers, and acceptable as a P&G-branded product. The designers considered materials and how they could avoid using high-paid, specialized suppliers. Some characteristics, such as packaging, could be adjusted to meet local cost standards. In other cases, a characteristic was nonnegotiable—such as corporate social-responsibility issues. For example, P&G wanted to ensure that none of the suppliers to its diaper business used child labor. In the end, P&G succeeded by understanding both the critical elements of the brand and the emerging-market customers’ expectations.

Nuances of Product Extension, Adaptation, and Invention

The product-adaptation strategy is easier for firms to execute than product invention. Nonetheless, even product adaptation requires understanding the local market well. Consider Ford Motor Company’s missteps in adapting its midpriced car model to the Indian market. Ford realized that it needed to lower the cost of its car to make it more affordable to Indian consumers. Ford brought a team of designers together in Detroit and tasked them with figuring out how to reduce the cost of the car. The designers looked at removing nonessential elements. The first feature to go was air conditioning. Next, the team decided to remove power windows in the back, keeping them only in the front. These and other such tweaks brought the total cost of the car down from $20,000 to $15,000. Reducing the cost by 25 percent is notable, but unfortunately the design team lacked vital local knowledge about India. First, even though the price of the car was lower, the $15,000 price point in India is still way above what the middle class can afford. The Indians who can afford a $15,000 car are the very rich. Second, the very rich in India who can afford to pay $15,000 for a car can also afford (and will have) a chauffeur. Remember the clever idea of removing the air conditioning and the power windows in the back? The consequence is that the chauffeur is the only one who gets a breeze. Given the sweltering summer temperatures and traffic congestion in Indian cities, you can guess that the Ford car didn’t sell well.Vijay Govindarajan, “Ten Rules for Strategic Innovators” (presentation, World Innovation Forum, New York, NY, May 5–6, 2009).

Country-of-Origin Effect

The country-of-origin effectA situation in which consumers use the country where a product was made as a barometer for evaluating the product’s quality. Their perceptions of the country influence whether they perceive the product favorably or unfavorably and thus whether they’ll purchase the product. refers to consumers using the country where the product was made as a barometer for evaluating the product. Their perceptions of the country influence whether they will perceive the product favorably or unfavorably. That perception influences consumers’ purchasing decisions. For example, France is known for its wines and luxury goods. Wines from Chile may be just as good and more affordably priced, but consumers may perceive French wines to be better due to the country-of-origin effect. In the 1960s, “Made in Japan” was a signal of low quality, but over time Japan has changed that perception through a dedicated focus on high quality. Specifically, Japan adopted Total Quality Management (TQM)A set of management practices initially introduced by W. Edwards Deming. The focus of TQM is increasing quality and reducing errors in production or service delivery. TQM consists of systematic processes, planning, measurement, continuous improvement, and customer satisfaction. which is a set of management practices initially introduced to Japan by W. Edwards Deming. The focus of TQM is increasing quality and reducing errors in production or service delivery. TQM consists of systematic processes, planning, measurement, continuous improvement, and customer satisfaction. These days, “made in Japan” is viewed positively, but “made in China” faces more of a stigma. Likewise, consumers in Colombia don’t want products that are made in Colombia. A similar problem happens with Mercedes-Benz—Mercedes-Benz cars assembled in Egypt have much lower resale value than those assembled in Germany. In these cases, local assembly in Egypt might be taken as a sign of inferior quality.

Reverse Innovation: How Designing for Emerging Economies Brings Benefits Back Home

Increasingly, marketing and innovation are directly linked. Reverse innovationDesigning a product for a developing country and bringing that innovation back to the home country. means designing a product for a developing country and bringing that innovation back to the home country. Creating new products and services for developing countries requires radical innovation and opens new opportunities in developed-world markets as well. For example, GE Healthcare sells sophisticated medical-imaging devices around the world. Historically, GE has sold these high-end machines in emerging economies like India. But only 10 percent of Indian hospitals can afford a $10,000 electrocardiogram (ECG) machine. Reaching the other 90 percent of the market takes more than simply cutting a few costs. It requires radical innovation and an in-depth understanding of local conditions.

One important local fact to know is that most Indians live in rural areas. That means they don’t have a local hospital to visit. Therefore, medical equipment needs to go to them, and no rural health care clinic is going to lug a $10,000 ECG machine into the field even if it could afford the device. Achieving the goal of a lightweight, reliable, simple-to-use ECG device took radical rethinking. GE built such a device that could fit in a shoulder bag or backpack. The device has a built-in replaceable printer and costs only $500. In addition, because the device would be used in rural locations with scant access to electricity, GE designed a battery that could do 500 ECGs on one charge. To make it easy to use, GE designed the device to have only three buttons. Finally, just because the device is inexpensive doesn’t mean it’s dumb. GE installed professional-level analysis software to aid rural doctors.

With its new portable ECG device, GE has unlocked a whole new market in developing countries. Beyond that, GE has also opened up new opportunities back home—and that’s the reverse innovation side of the story. How? The portable ECG machine with a $500 price tag is ideal for use in ambulances, saving lives of accident victims in developed countries as well. Cheap, portable, and easy-to-use devices are desirable in any country.Vijay Govindarajan, “Reverse Innovation: A New Strategy for Creating the Future” (webinar, HSM Global, March 18, 2010), accessed November 23, 2010, http://us.hsmglobal.com/contenidos/hsm-webinars-vijay.html.,“An ECG for Less Than Rs 10? New, Made-in-India, GE Device, Does IT,” India Tech Online, November 25, 2009, accessed August 1, 2010, http://www.indiatechonline.com/ge-mac-i-ecg-168.php.

Key Takeaways

- There are three strategies for introducing a company’s product to a new international market: (1) straight product extension, (2) product adaptation, and (3) product invention.

- A straight product extension involves taking the company’s current product and selling it in other countries without making changes to the product. The advantages of this strategy are that the company doesn’t need to invest in new research and development or manufacturing. The disadvantages, however, are that its products may not be well suited to local needs and that the products may be more costly due to higher US manufacturing and labor costs.

- Product adaptation refers to modifying the company’s existing product in a way that makes it fit better with local needs, as Nokia did by making its mobile phones for India dust-resistant.

- Product invention means creating an entirely new product for the target market, as P&G did by designing a diaper for emerging markets that cost the same as a single egg. Such a price would make the diaper affordable in emerging-market countries.

- When adapting or inventing a product for a new market, it’s important to have local knowledge, as the missteps of Ford’s car for India have shown. In addition, the country-of-origin effect influences consumers’ purchasing decisions. If consumers perceive one country more favorably than another, they’re more apt to buy products from that country.

- Inventing a new product for an international country can bring benefits back to the home market. GE Healthcare completely reinvented a $10,000 medical-imaging device to create a $500 portable, imaging device for the Indian market. In the process, GE realized it had created a new product for its home market as well.

Exercises

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- Describe three strategies for introducing a product to a new international market.

- Why might a company want to adapt its product to a local country rather than doing a straight product extension?

- What are the challenges of the product-invention strategy?

- Could the country-of-origin effect be used to a company’s advantage?

- Explain reverse innovation and the potential advantages it brings.

14.4 Global Sourcing and Distribution

Learning Objectives

- Understand the advantages of global sourcing.

- Know the pros and cons of sole-sourcing and multisourcing.

- Describe the distribution-management choices companies have when entering new international markets.

Global sourcingBuying the raw materials or components that go into a company’s products from around the world, not just from the headquarters’ country. refers to buying the raw materials or components that go into a company’s products from around the world, not just from the headquarters’ country. For example, Starbucks buys its coffee from locations like Colombia and Guatemala. The advantages of global sourcing are quality and lower cost. Global sourcing is possible to the extent that the world is flat—for example, buying the highest-quality cocoa beans for making chocolate or buying aluminum from Iceland, where it’s cheaper because it’s made using free geothermal energy.

When making global-sourcing decisions, firms face a choice of whether to sole-sourceTo buy raw materials, components, or services from one supplier exclusively, rather than buying from two or more suppliers. (i.e., use one supplier exclusively) or to multisource (i.e., use multiple suppliers). The advantage of sole-sourcing is that the company will often get a lower price by giving all of its volume to one supplier. If the company gives the supplier a lot of business, the company may have more influence over the supplier for preferential treatment. For example, during a time of shortage or strained capacity, the supplier may give higher quantities to that company rather than to a competitor as a way of rewarding the company’s loyalty.

On the other hand, using multiple suppliers gives a company more flexibility. For instance, if there’s a natural disaster or other disruption at one of their suppliers, the company can turn to its other suppliers to meet its needs. For example, when Hurricane Mitch hit Honduras with 180-mile-per-hour winds, 70 to 80 percent of Honduras’s infrastructure was damaged and 80 percent of its banana crop was lost. Both Dole Food Company and Chiquita bought bananas from Honduras, but Dole relied more heavily on bananas from Honduras than from other countries. As a result, Dole lost 25 percent of its global banana supply, but Chiquita lost only 15 percent.Yossi Sheffi, The Resilient Enterprise (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 216–17. In the aftermath, Chiquita’s revenues increased, while Dole’s decreased.

Sole-Sourcing Advantages

- Price discounts based on higher volume

- Rewards for loyalty during tough times

- Exclusivity brings differentiation

- Greater influence with a supplier

Sole-Sourcing Disadvantages

- Higher risk of disruption

- Supplier has more negotiating power on price

Multisourcing Advantages

- More flexibility in times of disruption

- Negotiating lower rates by pitting one supplier against another

Multisourcing Disadvantages

- Quality across suppliers may be less uniform

- Less influence with each supplier

- Higher coordination and management costs

Whichever sourcing strategy a company chooses, it can reduce risk by visiting its suppliers regularly to ensure the quality of products and processes, the financial health of each supplier, and the supplier’s adherence to laws, safety regulations, and ethics.

Ethics in Action

The Case of Global Sourcing

While there is little systematic research on questions related to ethics and global sourcing, one recent survey in the context of clothing manufacturers identified the following most encountered issues:Mike Pretious and Mary Love, “Sourcing Ethics and the Global Market: The Case of the UK Retail Clothing Sector,” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 34, no. 12 (2006): 892–903.

- Child labor. Forty-three percent of the respondents had encountered factories where child labor was being used. India, China, Thailand, and Bangladesh were cited as the worst offenders in this regard, partly because of the absence or unreliability of birth certificates, but also because of the difficulty that Westerners have in assessing the age of workers in these countries. Buyers relied on the management of the factory to check on documents supplied by the employee.

- Dangerous working conditions and health and safety issues. Forty-three percent of the respondents had encountered dangerous working conditions in factories. These included unsafe machinery (e.g., machine guards having been removed to speed up production), workers failing to use safety equipment such as cutting gloves, and the use and storage of hazardous chemicals (e.g., those used for dyeing and printing). Fire regulations were also sometimes inadequate, both in factories and in the dormitory accommodation often provided for workers who live away from their home regions. Sometimes fire exits were locked, and fire extinguishers were missing.

- Bribery and corruption. Thirty-one percent of respondents said that they had experienced bribery and corruption. One blatantly fraudulent practice mentioned was for suppliers to mislead the buyer over the true source of production. Many suppliers claim that goods are made in one factory, then transfer the production elsewhere, making it difficult for the retailer to audit.

- Exploitation of the workforce. Twenty-five percent of respondents mention some aspect of exploitation of the workforce, encompassing the issues of child labor and health and safety. However, it can also cover low wages being paid to workers and excessive overtime being expected by employers. Respondents specifically mentioned that they had encountered worker exploitation. Many spoke of long working hours in factories, especially at peak periods, with employees often working over seventy hours per week.

Distribution Management

Selling internationally means considering how your company will distribute its goods in the market. Developed countries have good infrastructure—passable roads that can accommodate trucks, retailers who display and sell products, and reliable communications infrastructure and media choices. Emerging markets, on the other hand, often have very fragmented distribution networks, limited logistics, and much smaller retailer outlets. Hole-in-the-wall shops, door-to-door peddlers, and street vendors play a much larger role in emerging-market countries. In the emerging countries of Africa, for example, books might be sold from the back of a moped.

In addition, the standards of living in emerging countries vary widely. Most of the middle class lives in cities, but the percentage of the population that lives in rural areas varies by country. In India, 70 percent of the population lives in rural areas, whereas in Latin America only 30 percent does.

Rural logistics are especially problematic. Narrow dirt roads, weight-limited bridges, and mud during the rainy season hamper the movement of goods. An executive at computer storage device manufacturer EMC noted that sometimes the company’s refrigerator-sized, data-storage systems have had to be transported on horse-drawn wagons.

How Nokia Tackles Distribution Challenges

Nokia is a $59 billion company with over 123,000 employees.“Nokia Corporation Company Profile,” Hoovers, accessed August 6, 2010, http://www.hoovers.com/company/Nokia_Corporation/crxtif-1-1njdap.html. It sells 150 different devices, of which 50 to 60 are newly introduced each year. Each device can be customized on many variants, including language and content. This variation adds greatly to the devices’ complexity; three hundred to four hundred components need to arrive on time at factories in order for the devices to be built. Approximately one billion people use Nokia devices worldwide. Countries like China, India, and Nigeria, which ten years ago had almost zero penetration of mobile phones, now have twenty million to forty million users each. Emerging markets now account for over half of Nokia’s annual sales.

Nokia has the challenge of selling a growing variety of mobile devices in hundreds of thousands of tiny retail outlets in the developing world. To tackle reaching its rural customers in developing countries, Nokia has 350,000 points of presence in rural areas, from small kiosks and corner shops to organized retail outlets. Nokia has 100,000 such point-of-sale (POS) outlets in India, 80,000 in China, and 120,000 in the Middle East and Africa.

To train salespeople in developing countries, Nokia created an internal university to educate the people who sell its phones in these POS locations—an average of five people per location. Nokia Academy teaches local salespeople about the features of the phones and how to sell them. As Nokia expands further into these emerging markets, it will penetrate deeper into the rural areas and will distribute through local providers.

Nokia’s challenge is to maintain its strong brand name—the fifth most recognized brand in the world—across these POS locations. Meeting this challenge has taken years. One way that Nokia maintains control of its brand across these locations is by having managers visit the outlets on a regular basis and using their mobile phones to photograph the shelf layout at each location. This lets Nokia control quality and improve merchandizing techniques at all locations.

Distribution-Management Choices: Partner, Acquire, or Build from Scratch

There are typically three distribution strategies for entering a new market. First, companies can do a joint-venture or partnership with a local company. This is the strategy Walmart used when entering Mexico. A second strategy is to acquire a local company to have immediate access to large-scale distribution. The Home Depot pursued this strategy in China when it acquired a partner with whom it had been working for quite some time. Third, a company can to build its own distribution from scratch. Retailer Carrefour chose this route in China years ago, because it knew China would offer a big opportunity, and Carrefour wanted to develop its own local capabilities. Which strategy the company chooses depends on its timetable for volume in the market, local foreign-ownership laws, and the availability of suitable partners or acquisition targets.

Spotlight on International Strategy and Entrepreneurship

Unilever Solves Distribution Issues in India

Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL), Unilever’s Indian subsidiary, wanted to reach the 70 percent of Indians who live in rural villages. This underserved market is very hard to reach. Not only is marketing to remote villages difficult, but the physical transport of products is no easier. Most of the villages lack paved roads, making traditional truck-based distribution arduous. The only way to reach many of these remote villages is by single-track dirt trails.

In response to these conditions, HUL has created Project Shakti (the word means “strength”) and developed a network of 14,000 women and women-owned cooperatives to serve 50,000 villages. The women handle the logistics and door-to-door retailing of a range of personal-care products. To address the needs of the market and this novel distribution system, HUL has packaged its products in much smaller sizes. The effort has created $250 million in new revenues for HUL, of which 10 percent is used for financing the women entrepreneurs. By using this approach, HUL doesn’t have to deal with the problem of moving products in rural India. The women or their employees come to the company’s urban distribution centers to get the products.

Key Takeaways

- Global sourcing refers to buying the raw materials or components that go into a company’s products from around the world, not just from the headquarters’ country. The advantages of global sourcing include access to higher quality or lower prices.

- When making sourcing decisions, companies must decide whether to sole-source (i.e., to use one supplier exclusively) or to use two or more suppliers. Sole-sourcing can bring advantages of price discounts based on volume and may give the company greater influence over a supplier or preferential treatment during times of constrained capacity Sole-sourcing can also bring advantages of differentiation or high quality. The disadvantages of sole-sourcing, however, are that the company faces a higher risk of disruption if something happens to that supplier. Also, the supplier may hold more negotiating power on price.

- A company typically has three distribution strategies for entering a new market—to engage in a joint venture, to acquire a local company, or to build its own distribution network from scratch. Establishing a partnership or joint venture is the least costly approach, followed by acquisition. Building a distribution network from scratch is the most costly and time consuming, but it may give the company the most local experience and capabilities for the long term.

- Distribution channels in emerging markets are less developed, which means that companies may need to seek novel solutions to distributing their products, such as Hindustan Unilever Limited creating its own distribution network of 14,000 female independent distributors and cooperatives or Nokia creating Nokia Academy to train salespeople.

Exercises

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- Describe three distribution strategies that companies can use when entering a new market.

- What challenges do companies face when distributing products internationally?

- What are the distribution challenges in emerging-market countries?

- When making a sourcing decision, would you choose to sole-source or multisource? Why?

- What are the advantages of global sourcing?

14.5 Global Production and Supply-Chain Management

Learning Objectives

- Understand the differences between outsourcing and offshoring.

- Explain three strategies for locating production operations.

- Know the value of supply-chain management.

Strategic Choices: Export, Local Assembly, and Local Production

When deciding where and how to produce products for international markets, companies typically have a choice of three strategies. The strategies vary in terms of levels of risk, cost, exposure to exchange-rate fluctuations, and leveraging of local capabilities. Companies need to tailor their strategy to fit their product and the country.

Manufacture in the United States and Then Export

The lowest-investment production strategy is to make the product at the company’s existing manufacturing locations and then export them to the new market. Companies use this solution in situations where the total opportunity in the new market doesn’t justify opening a plant. For example, EMC supplies its Asia-Pacific customers from plants in the United States and Ireland. This strategy does have several downsides. Specifically, the company faces higher shipping costs, importation delays, local import duties, risks due to exchange-rate fluctuations, and isolation from local knowledge.

Global Components with Local Assembly

The next level of strategy uses of out-of-country suppliers but local assembly. Dell Latin America uses this approach. It buys high-tech computer components globally but performs customized assembly in Brazil. Being closer to the market improves Dell’s sales, service, and customer knowledge.

Another example is Iams. Iams makes its proprietary pet food in the United States and ships it to other countries for packaging. This strategy lets Iams do some local customization and offer better customer response, while gaining tax or tariff incentives from local assembly.