This is “Winning through Effective, Global Talent Management”, chapter 12 from the book Challenges and Opportunities in International Business (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 12 Winning through Effective, Global Talent Management

What’s in It for Me?

- What is the scope and changing role of global, strategic human resources management (SHRM) in international business?

- How can you visualize the battlefield in the global war for talent?

- How can you engage in effective selection and placement strategies?

- What are the roles of pay structure and pay for performance in effective talent management?

- How can you use the Workforce Scorecard to gauge and proactively manage human capital, including your own?

You’ve probably heard the saying “people make the place.” Moreover, firms with operations across borders have this added advantage: access to the best and brightest people from around the world, because talent isn’t constrained by national borders. Indeed, one of the key forces in flattening the world is new technologies; other trends too are empowering people from every corner of the earth. At the same time, companies large and small are able to find and leverage human capital from the farthest reaches of the planet. This ability to arbitrage and attract human capital worldwide is a key driver in the the war for talent, which is a term signifying the strategic importance of attracting top employees to work for your company. In today’s fast-changing environment, companies need employees who understand the organization’s strategy and are empowered to execute it. To achieve this, organizations need to follow a strategic human resources management (SHRM) approach. SHRM ensures that people are a key factor in a firm’s competitive advantage. Organizations need human resources to be a partner in identifying, recruiting, and hiring the types of employees who will be most qualified to help the company achieve its goals. SHRM requires attracting the right employees to the company, identifying metrics to help employees stay on target to meet the company’s goals, and rewarding them appropriately for their efforts so that they stay engaged and motivated. Having all these components in place results in a high-performance work system, improves organizational performance, and unleashes employee talent.

Opening Case: Employee Recruitment, Selection, and Development Strategies at Enterprise Holdings

You may know this company through one of its businesses, Enterprise Rent-A-Car, and its “We’ll pick you up” jingle. The Enterprise car-rental business is part of a much larger family business—Enterprise Holdings. Through its regional subsidiaries, Enterprise Holdings operates more than 1 million cars and trucks, the largest fleet of passenger vehicles in the world today.“Enterprise Holdings Announces Fiscal 2010 Highlights,” MarketWire, September 30, 2010, accessed November 24, 2010, http://www.marketwire.com/press-release/Enterprise-Holdings-Announces-Fiscal-2010-Highlights-1328012.htm. It’s one of the largest and most comprehensive providers in the car-rental industry, serving approximately 7,600 neighborhood and airport locations in the United States, Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, Latin America, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Germany, and Asia. In addition, Enterprise Holdings is part of a global strategic alliance with Europcar, creating the world’s largest car-rental network. In this case study, you’ll see how Enterprise—with more than 68,000 employees and $12 billion revenue—ensures it has the right people with the right skills in the right locations worldwide.

Core Values from the Start

Enterprise was founded in 1957 by Jack Taylor, who returned from World War II to start a car-leasing company in St. Louis. He launched with a total of seven cars and one employee, but he had a vision to grow and a strong motto: “Take care of your customers and your employees first, and the profits will follow.”“Heritage,” Enterprise Holdings, accessed January 28, 2011, http://www.enterpriseholdings.com/about-us. This vision of exceptional customer service means that Enterprise has to identify, attract, and hire employees who would be good at delivering on its customer service mission. To accomplish this, Enterprise looks for potential new hires who have the following set of skills and competencies that support the company’s objectives:

- Customer service focus

- Sales and listening skills

- Positive work ethic (a drive to achieve results)

- Leadership aptitude

- Communication skills

- Flexibility

The company has identified the competencies and behaviors that such skills provide and has clearly articulated the benefits that these skills provide to Enterprise. For instance, flexibility is defined as dealing well with challenges, demonstrating resilience, and being able to prioritize. Enterprise believes that it—the company—is better able to cope with changing circumstances when an employee exhibits flexibility.

Enterprise describes the competencies it seeks on its website so that job seekers can determine for themselves whether they will measure up and fit in with the Enterprise culture.

Attracting and Recruiting Employees

Enterprise has a team of 200 recruiters whose job is to identify potential new candidates at over one hundred college campuses each year.“Recruitment and Selection at Enterprise Rent-A-Car,” The Times 100, 2009, accessed May 10, 2011, http://www.thetimes100.co.uk/downloads/enterprise/enterprise_14_full.pdf. Given its growth and international expansion, Enterprise hires 8,000 college graduates a year to fill its future management needs.Seth Cline, “The Companies Hiring the Most New College Grads,” Forbes, June 21, 2010, accessed January 27, 2011, http://www.forbes.com/2010/06/21/companies-hiring-college-graduates-leadership-careers-jobs.html? boxes=leadershipchannellatest. The recruiting function at Enterprise is decentralized: each recruiter is responsible for recruiting within his or her local market. The rationale for this structure is this: local hires reflect the local community for each branch office. “We try to mirror our communities,” says Pam Webster, assistant vice president for recruiting at Enterprise.Fay Hansen, “Enterprise’s Recruiting Model Transforms Interns into Managers,” Workforce Management Online, May 2009, accessed January 30, 2011, http://www.workforce.com/section/recruiting-staffing/feature/enterprises-recruiting-model-transforms-interns-into/index.html.

Enterprise also uses an internship program as a way to identify potential future employees. The program is open to college juniors and seniors; interested interns then spend a summer working at Enterprise after graduating. Recruiters stay in touch with interns during the school year through e-mails and lunches. Some even send a care package to interns during final exam time.

In the United Kingdom, Enterprise began using Campus Brand Managers on university campuses to find potential interns and job applicants. These Campus Brand Managers are interns or students who already work for Enterprise and who act as liaisons for potential applicants.“Recruitment and Selection at Enterprise Rent-A-Car,” The Times 100, 2009, accessed May 10, 2011, http://www.thetimes100.co.uk/downloads/enterprise/enterprise_14_full.pdf.

Enterprise also has an employee-referral program through which current employees get a financial reward if they recommend a new employee to Enterprise and that candidate is hired into a full-time position. The referral program has been the company’s primary source of minority and female hires, and approximately 40 percent of new hires join Enterprise that way.Fay Hansen, “Enterprise’s Recruiting Model Transforms Interns into Managers,” Workforce Management Online, May 2009, accessed January 30, 2011, http://www.workforce.com/section/recruiting-staffing/feature/enterprises-recruiting-model-transforms-interns-into/index.html.

Finally, Enterprise recruits online; about 50 percent of Enterprise’s UK and Ireland workforce is recruited via the web.

Developing Employees

To develop new recruits who would like to enter the ranks of management, Enterprise offers its Graduate Management Trainee program, which is a program that teaches management skills such as leadership and big-picture thinking; finance and business management skills such as cost control and attention to profits; sales and marketing skills to generate more sales; fleet-control skills such as handling repairs and getting the right number and type of cars; and of course customer service skills. In as little as eight to twelve months, trainees can become assistant managers. Once they become assistant managers, they start to earn performance pay in addition to their salaries.David Lagess, “A ‘Stealth Company’ No Longer,” U.S. News & World Report, October 17, 2008, accessed January 27, 2011, http://money.usnews.com/money/business-economy/small-business/articles/2008/10/17/a-stealth-company-no-longer?PageNr=2. The performance pay is based on branch profits, which means employees can directly benefit from the improvements they make to branch operations.

Enterprise’s training program supports the company’s promote-from-within philosophy. “We have always hired college grads into our management training program, and from there we promote entirely from within,” says Marie Artim, assistant vice president of recruiting. “It’s where I started, it’s where our CEO started, and it’s where almost all our senior leadership started.”Seth Cline, “The Companies Hiring the Most New College Grads,” Forbes, June 21, 2010, accessed January 27, 2011, http://www.forbes.com/2010/06/21/companies-hiring-college-graduates-leadership-careers-jobs.html? boxes=leadershipchannellatest. Enterprise Holdings’ president and chief operating officer (COO), Pamela Nicholson, started as a management trainee in 1981, working behind the rental counter, as did current chairman and CEO Andy Taylor.Anne Fisher, “Get a Great Job after Graduation,” Fortune, May 28, 2009, accessed January 27, 2011, http://money.cnn.com/2009/05/28/news/economy/new.grad.jobs.fortune/index.htm?postversion=2009052904. Nicholson moved steadily through the ranks of the company and in 1999 was promoted to senior vice president of the company’s North American operations, then to COO in 2003, and to president in 2008.“An Interview with Pamela M. Nicholson, President and Chief Operating Officer, Enterprise Holdings,” Leaders 34, no. 1 (January–March 2011), accessed January 27, 2011, http://www.leadersmag.com/issues/2011.1_Jan/Missouri/LEADERS-Pamela-Nicholson-Enterprise-Holdings.html.

Global Entrepreneurship

In addition to customer service, entrepreneurship is another key corporate value at Enterprise. The tradition began with founder Jack Taylor and continued through innovations introduced by Enterprise’s branch managers. For example, in 1974 a rental manager in Orlando decided to offer his customers a new service: a free ride to the Enterprise rental office. Other branches emulated this free pick-up service, which demonstrated that employees with a great idea can see it implemented across the company.

Other entrepreneurial ideas include WeCar, which is Enterprise’s new car-sharing program for corporations and campuses.David Lagess, “A ‘Stealth Company’ No Longer,” U.S. News & World Report, October 17, 2008, accessed January 27, 2011, http://money.usnews.com/money/business-economy/small-business/articles/2008/10/17/a-stealth-company-no-longer?PageNr=2. For example, Google is using the WeCar program and lets its employees choose among Priuses and Ford Escape Hybrids that Enterprise provides.Elizabeth Olson, “Car Sharing Reinvents the Company Wheels,” New York Times, May 6, 2009, accessed January 27, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/07/business/businessspecial/07CAR.html?_r=1&ref=businessspecial.

Expanding internationally is likewise done through entrepreneurial employees. Enterprise opened its first German office in Ottobrunn in 1997. Enterprise’s German pioneer, Jack Cope, said, “It’s a lot of fun taking something from nothing and making it big, and I’m on my way to making that happen. A few years ago, Enterprise was unknown here in Germany. Today, thanks to the efforts of our motivated German workforce, the Enterprise mission, philosophy and culture are catching on.”“For Management Trainees, Ours Really Is a World of Opportunity,” About Enterprise, Enterprise Rent-A-Car, accessed January 27, 2011, https://www.enterprisealive.com/about-enterprise/global-locations.

The company entices international entrepreneurs through messages like the following one on its website:

Just imagine the possibilities that come with joining a huge, internationally successful company with a personal, entrepreneurial approach which allows individuals to stand out. Our secret lies in the fact that we’re divided up into thousands of smaller, local businesses. So when you take one of our graduate trainee jobs, you’ll be learning how to run the business yourself. And how many organizations with a $12 billion turnover can say that?“With a Company as Successful as Ours, It’s Easy to Start Getting Ahead of Yourself,” About Enterprise, Enterprise Rent-A-Car, accessed January 27, 2011, http://www.enterprisealive.com/about-enterprise/our-industry.

Opening Case Exercises

(AACSB: Ethical Reasoning, Multiculturalism, Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- How does Enterprise use SHRM to support its customer service objectives?

- What strategies does Enterprise use to attract new employees?

- Do you think entrepreneurial employees would be motivated to work at Enterprise? Why or why not?

12.1 The Changing Role of Strategic Human Resources Management in International Business

Learning Objectives

- Understand how human resources management is becoming a strategic partner.

- Recognize the importance of an organization’s human capital.

- Learn the key elements of SHRM.

HR as a Strategic Partner

The role of human resources management (HRM) is changing in business, particularly in international business. Previously considered a support function, HRM is now becoming a strategic partner in helping a global company achieve its goals. The strategic approach to HRM—strategic human resources management (SHRM)An organizational approach to human resources management (HRM) with a concern for the effects of HRM practices on firm performance.—means going beyond administrative tasks such as payroll processing. Instead, as shown in the opening case on Enterprise, managers need to think more broadly and deeply about how employees will contribute to the company’s success.

SHRM is not just a function of the human resources (HR) department—all managers and executives need to be involved because the role of people is so vital to a company’s competitive advantage.Brian E. Becker and Mark A. Huselid, “Strategic Human Resources Management: Where Do We Go from Here?,” Journal of Management 32, no. 6 (2006): 898–925. In addition, organizations that value their employees are more profitable than those that don’t.Mark A. Huselid, “The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Turnover, Productivity, and Corporate Financial Performance,” Academy of Management Journal 38, no. 3 (1995): 635–72; Jeffrey Pfeffer, The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998); Jeffrey Pfeffer and John F. Veiga, “Putting People First for Organizational Success,” Academy of Management Executive 13, no. 2 (1999): 37–48; Theresa M. Welbourne and Alice O. Andrews, “Predicting Performance of Initial Public Offering Firms: Should HRM be in the Equation?,” Academy of Management Journal 39, no. 4 (1996): 910–11. Research shows that successful organizations have several things in common: providing employment security, engaging in selective hiring, using self-managed teams, being decentralized, paying well, training employees, reducing status differences, and sharing information.Jeffrey Pfeffer and John F. Veiga, “Putting People First for Organizational Success,” Academy of Management Executive 13, no. 2 (1999): 37–48. When organizations enable, develop, and motivate human capital, they improve accounting profits as well as shareholder value in the process.Brian E. Becker, Mark A. Huselid, and David Ulrich, “Six Key Principles for Measuring Human Capital Performance in Your Organization” (working paper, School of Management and Labor Relations, Department of Human Resources Management, Rutgers, State University of New Jersey, 2002). The most successful organizations manage HR as a strategic asset and measure HR performance in terms of its strategic impact. When each piece is in the right place, it creates a high-performance work system (HPWS)A set of management practices that attempts to create an environment within an organization in which the employee has greater involvement and responsibility.—a set of management practices that attempt to create an environment within an organization in which the employee has greater involvement and responsibility.

The following are some questions that HRM should be prepared to answer in this new world:David Ulrich, Delivering Results (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998).

- Competence. To what extent does our company have the required knowledge, skills, and abilities to implement its strategy?

- Consequence. To what extent does our company have the right measures, rewards, and incentives in place to align people’s efforts with the company strategy?

- Governance. To what extent does our company have the right structures, communications systems, and policies to create a high-performing organization?

- Learning and Leadership. To what extent can our company respond to uncertainty and learn and adapt to change quickly?

Crucial Role of SHRM in Global Firms

Developing an effective international workforce is much more difficult for a competitor to emulate than buying technology or securing capital.Dennis R. Briscoe, Randall S. Schuler, and Lisbeth Claus, International Human Resource Management, 3rd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2009). Besides, how well companies manage their HR around the world can mean the difference between success and failure. In a nutshell, firms that effectively manage their international HR typically outperform competitors in terms of identifying new international business opportunities, adapting to changing conditions worldwide, sharing innovation knowledge throughout the firm, effectively coordinating subsidiary operations, conducting successful cross-border acquisitions, and maintaining a high-performing, committed overseas workforce.Mary Yoko Brannen and Mark F. Peterson, “Merging without Alienating: Interventions Promoting Cross-cultural Organizational Integration and Their Limitations,” Journal of International Business Studies 40 (2009): 468–89; Yaping Gong, “Toward a Dynamic Process Model of Staffing Composition and Subsidiary Outcomes in Multinational Enterprises,” Journal of Management 29, no. 2 (2003): 259–80; Dana Minbaeva, Torben Pedersen, Ingmar Björkman, Carl F. Fey, and Hyeon Jeong Park, “MNC Knowledge Transfer, Subsidiary Absorptive Capacity, and HRM,” Journal of International Business Studies 34, no. 6 (2003): 586–99; Gary Oddou, Joyce S. Osland, and Roger N. Blakeney, “Repatriating Knowledge: Variables Influencing the ‘Transfer’ Process,” Journal of International Business Studies 40, no. 2 (2009): 181–99.

Did You Know?

Robert Half International (RHI), a professional consulting firm, has staffing operations in more than 400 locations worldwide.“About Us,” Robert Half International, accessed January 28, 2011, http://www.rhi.com/AboutUs. During the recession of 2009, RHI began hiring older, more experienced workers to add to its roster of temporary workers. Typically, temporary workers are low-level employees, but during the recession, many workers with fifteen or twenty years of experience lost their jobs or retired from full-time jobs. RHI hired older highly skilled workers, such as accounting and finance experts, to work on temporary projects—helping a company restructure or emerge from bankruptcy, for instance. The situation is a win-win: companies get access to experts they may not otherwise be able to afford, while retired workers earn extra money or income after a layoff. Zurich-based Adecco, a competitor to RHI, likewise hired older workers. “More companies are looking for flexible, highly skilled temporary employees because it’s much easier to end an assignment than terminate employment,” said Doug Arms, chief talent officer at Ajilon Professional Staffing, a unit of Adecco.Aili McConnon, “Temp Giant Robert Half Welcomes Boomers,” BusinessWeek, May 21, 2009, accessed January 28, 2011, http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/09_22/b4133054601320.htm.

In many multinationals, an important challenge is balancing the need to coordinate units scattered around the world with the need for individual units to have the control necessary to deal effectively with local issues.Randall S. Schuler, Pawan S. Budhwar, and Gary W. Florkowski, “International Human Resource Management,” in Handbook for International Management Research, ed. Betty-Jane Punnett and Oded Shenkar (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004), 356–414. Achieving this balance becomes more difficult as the level of diversity that firms are exposed to increases. For example, consider a situation where the parent firm’s national culture differs dramatically from the cultures in its overseas subsidiaries. In this case, it may be harder for the parent firm to share information, technology, and innovations between the home office and foreign outposts. It may also be more difficult to promote needed organizational changes and manage any conflicts that arise between employees in different countries.

Fortunately, international human resources management (IHRM) strategies can overcome such problems. For instance, IHRM professionals can help ensure that top executives understand the different cultures within the company workforce and around the world. They can also offer advice on how to coordinate functions across boundaries and develop outstanding cross-cultural skills in employees (e.g., through various training programs and career paths that involve significant overseas exposure).Dennis R. Briscoe, Randall S. Schuler, and Lisbeth Claus, International Human Resource Management, 3rd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2009); Carl F. Fey and Ingmar Björkman, “The Effect of Human Resource Management Practices on MNC Subsidiary Performance in Russia,” Journal of International Business Studies 32, no. 1 (2001): 59–75; Patrick M. Wright, Gary C. McMahan, and Abagail McWilliams, “Human Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage: A Resource-Based Perspective,” International Journal of Human Resource Management 5, no. 2 (1994): 301–26.

Of course, these are general suggestions and a range of HR practices might be used to implement them. Companies should develop an international HR philosophy that describes corporate values about HR—this in turn, will shape the broad outline of what constitutes acceptable IHRM practices for employees all over the world. From there, individual units can fine-tune and select specific practices that best fit their local conditions. But this is easier said than done, especially for firms operating in dozens of countries. Multinationals typically find it extremely difficult, for example, to design a compensation system that is sensitive to cultural differences yet still meets general guidelines of being seen as fair by employees everywhere. Indeed, culture may impact local HRM practices in a variety of ways—from how benefit packages are constructed to the hiring, termination, and promotion practices used, just to name a few.Dennis R. Briscoe, Randall S. Schuler, and Lisbeth Claus, International Human Resource Management, 3rd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2009).

Local cultures can impact HRM practices.

© 2011, Atma Global Inc. All rights reserved.

Nevertheless, selecting the right IHRM strategy can pay off, particularly in difficult foreign markets. Consider multinationals wanting to quickly enter countries with transitional economies—those that are moving from being state-dominated to being market-based (e.g., China and Russia). Choosing to enter those markets by buying local firms, building new plants, or establishing joint ventures may create significant HR challenges that will undercut performance if not handled well. Consequently, global firms need to adopt an appropriate IHRM strategy to meet transition economy challenges.

The Importance of Human Capital

Employees provide an organization’s human capitalThe collective sum of the attributes, life experiences, knowledge, inventiveness, energy, and enthusiasm that a company’s employees choose to invest in their work.. Your human capital is the set of skills that you have acquired on the job—through training and experience—which increase your value in the marketplace. The Society of Human Resource Management’s Research Quarterly defined an organization’s human capital as “the collective sum of the attributes, life experience, knowledge, inventiveness, energy, and enthusiasm that its people choose to invest in their work.”Leslie A. Weatherly, “Human Capital—the Elusive Asset; Measuring and Managing Human Capital: A Strategic Imperative for HR,” 2003 SHRM Research Quarterly, March 2003, accessed November 2, 2010, http://www.ispi.org/pdf/suggestedReading/6_Weatherly_HumanCapital.pdf.

Focus on Outcomes

Unfortunately, many HR managers are more effective in the technical or operational aspects of HR than they are in the strategic, even though the strategic facet has a much larger effect on the company’s success.Mark A. Huselid, Susan E. Jackson, and Randall S. Schuler, “Technical and Strategic Human Resource Management Effectiveness as Determinants of Firm Performance,” Academy of Management Journal 40, no. 1 (1997): 171–88. In the past, HR professionals focused on compliance to rules, such as those set by the federal government, and tracked simple metrics—for instance, the number of employees hired or the number of hours of training delivered. The new principles of management, however, require a focus on outcomes and results, not just numbers and compliance. Just as lawyers count how many cases they’ve won—not just how many words they used—so too must HR professionals track how employees are using the skills they’ve learned to attain goals, not just how many hours they’ve spent in training.David Ulrich, Delivering Results (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998).

John Murabito, executive vice president and head of Human Resources and Services at CIGNA, says that HR executives need to understand the company’s goals and strategy and then provide employees with the skills needed. Too often, HRM executives get wrapped up in their own initiatives without understanding how their role contributes to the business. That’s dangerous, because when it comes to the HR department, “anything that is administrative or transactional is going to get outsourced,” Murabito says.Jessica Marquez, “On the Front Line: A Quintet of 2006’s Highest-Paid HR Leaders Discuss How They Are Confronting Myriad Talent Management Challenges as Well as Obstacles to Being Viewed by Their Organizations as Strategic Business Partners,” Workforce Management 86, no. 5 (1997): 22. Indeed, the number of HRM outsourcing contracts over $25 million has been increasing, with nearly 3,000 active company contracts recently under way.“TPI Counts 2700+ Outsourcing Contracts,” SharedXpertise Forums, December 2007, accessed January 30, 2009, http://www.sharedxpertise.com/content/4301/tpi-counts-2700-outsourcing-contracts. For example, Bank of America outsourced its HRM administration to NorthgateArinso. NorthgateArinso now provides timekeeping, payroll processing, and payroll services for 10,000 Bank of America employees outside the United States.“Annual Report 2006,” Arinso International, accessed March 10, 2011, http://bib.kuleuven.be/ebib/data/jaarverslagen/Arinso_2006eng.pdf. To avoid being outsourced, HRM needs to stay relevant and accept accountability for its business results. In short, the people strategy needs to fully align with the company’s business strategy, keeping the focus on outcomes.

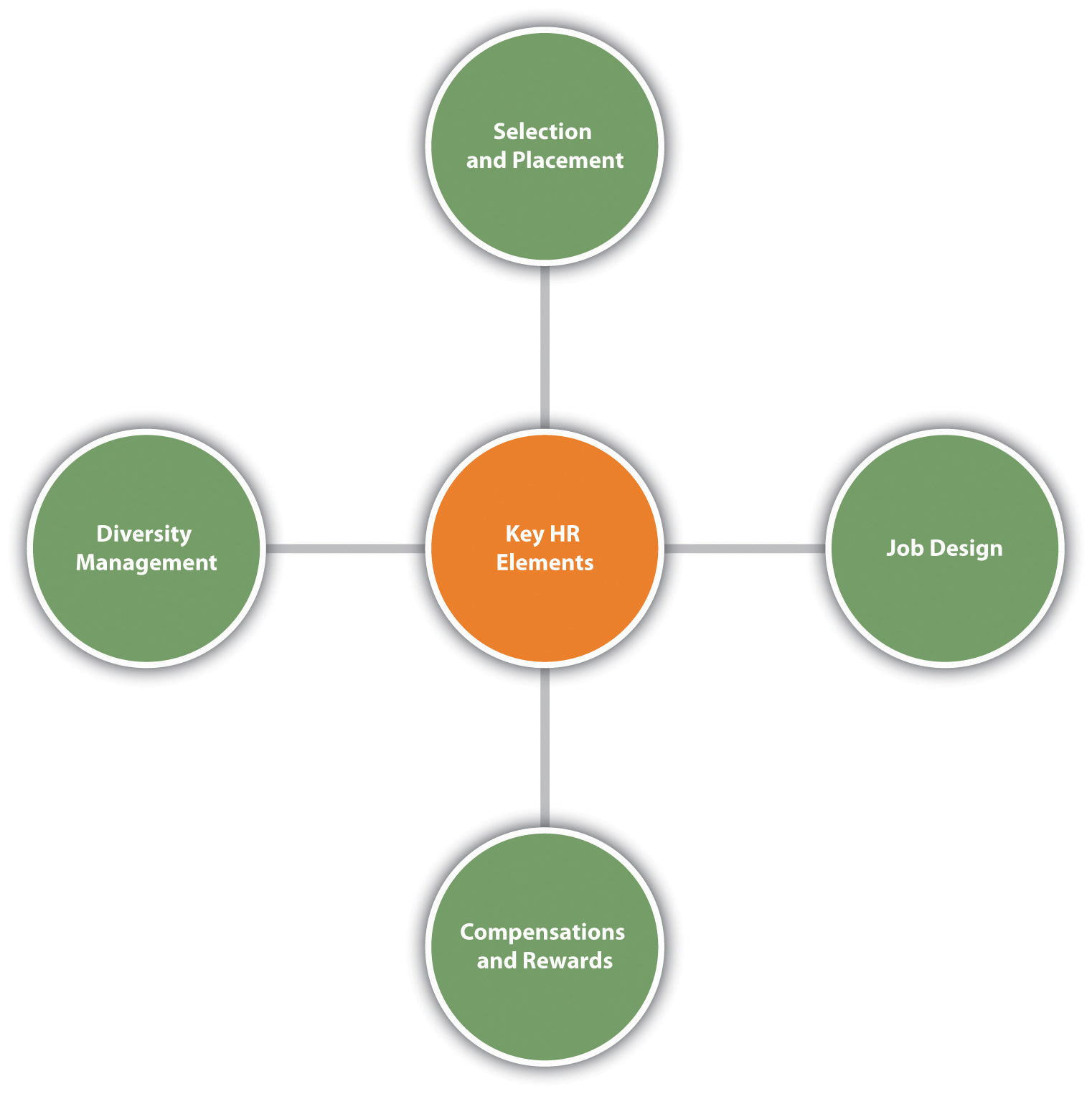

Key Elements of HRM

Beyond the basic need for compliance with HRM rules and regulations, the four key elements of HR are summarized in Figure 12.1 "Key HRM Elements". In high-performing companies such as Enterprise Holdings, each element of the HRM system is designed to reflect best practices and to maximize employee performance. The different parts of the HRM system are strongly aligned with company goals.

Figure 12.1 Key HRM Elements

Selection and Placement

It’s good for firms to acquaint prospective new hires with the nature of the jobs they’ll be expected to fulfill early in the hiring process. This includes explaining the technical competencies needed (e.g., collecting statistical data) and defining behavioral competencies. Behavioral competencies may have a customer focus, such as the ability to show empathy and support of customers’ feelings and points of view, or a work-management focus, such as the ability to complete tasks efficiently or to know when to seek guidance.

In addition, an SHRM best practice is to make the organization’s culture clear by discussing the values that underpin the organization. For example, firms can describe the “heroes” of the organization—those employees who embody the values of the organization. For example, a service company’s heroes may be the people who go the extra mile to get customers to smile. In a software company, the heroes may be the people who toil through the night to develop new code. By sharing such stories of company heroes with potential hires, the firm helps reinforce the values and behaviors that make the company unique. This, in turn, will help the job candidates determine whether they’ll fit well into that organization’s culture.

Job Design

Job designThe process of combining tasks to form a whole job while taking into account issues of the health and safety of the worker. refers to the process of combining tasks to form a whole job. The goal is to design jobs that involve doing a whole piece of work and that are challenging but ultimately doable for the employee. Job design also takes into account issues of health and safety of the worker. When planning jobs or assigning people to jobs, HR managers also consider training (ensuring that employees to have the knowledge and skills to perform all parts of their job) and giving them the authority and accountability to do so.Edward E. Lawler III, The Ultimate Advantage (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1992).

One company that does training right is Motorola. As a global company, Motorola operates in many countries, including China. Operating in China presents particular challenges in terms of finding and hiring skilled employees. In a recent survey conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai, 37 percent of US-owned enterprises operating in China said that recruiting skilled employees was their biggest operational problem.Kevin Lane and Florian Pollner, “How to Address China’s Growing Talent Shortage,” McKinsey Quarterly, no. 3 (2008), accessed March 10, 2011, http://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/How_to_address_Chinas_growing_talent_shortage_2156. Indeed, polled companies cited HRM as a problem more often than they cited regulatory concerns, bureaucracy, or infringement on intellectual property rights. This is because Chinese universities don’t turn out candidates with the skills that multinational companies need. As a result, Motorola has created its own training and development programs to bridge the gap. For example, Motorola’s China Accelerated Management Program is designed for local managers. Motorola’s Management Foundation program helps train managers in areas such as communication and problem solving. Finally, Motorola offers a high-tech MBA program in partnership with Arizona State University and Tsinghua University, so that top employees can earn an MBA in-house.Kevin Lane and Florian Pollner, “How to Address China’s Growing Talent Shortage,” McKinsey Quarterly, no. 3 (2008), accessed March 10, 2011, http://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/How_to_address_Chinas_growing_talent_shortage_2156. Such programs are tailor-made to the minimally skilled—but highly motivated—Chinese employees.

Figure 12.2 W. P. Carey and Motorola China High Technology MBA Program Graduation Ceremony

Source: W. P. Carey School of Business MBA China Programs.

Compensation and Rewards

The SHRM function also includes evaluating and paying people on the basis of their performance—not simply for showing up to the job. Firms must offer rewards for skill development and organizational performance, emphasizing teamwork, collaboration, and responsibility for performance. Good compensation systems include incentives, gainsharing, profit sharing, and skill-based pay that rewards employees who learn new skills and put those skills to work for the organization. Employees who are trained in problem solving and a broad range of skills are more likely to grow on the job and feel more satisfaction. Their training enables them to make more valuable contributions to the company, which, in turn, gains them higher rewards and greater commitment to the company.William F. Barnes, “The Challenge of Implementing and Sustaining High Performance Work Systems in the United States: An Evolutionary Analysis of I/N Tek and Kote” (PhD diss., University of Notre Dame, 2001). Likewise, the company benefits from employees’ increased flexibility, productivity, and commitment.

When employees have access to information and the authority to act on that information, they’re more involved in their jobs, more likely to make the right decision, and more inclined to take the necessary actions to further the organization’s goals. Similarly, rewards need to be linked to performance so that employees are naturally inclined to pursue outcomes that will earn rewards and further the organization’s success at the same time.Mason Carpenter, Talya Bauer, and Berrin Erdogan, Principles of Management (Nyack, NY: Flat World Knowledge, 2009), accessed January 5, 2011, http://www.flatworldknowledge.com/printed-book/127834.

Diversity Management

Another key to successful SHRM in today’s business environment is embracing diversity. In past decades, “diversity” meant avoiding discrimination against women and minorities in hiring. Today, diversity goes far beyond this limited definition; diversity management involves actively appreciating and using the differing perspectives and ideas that individuals bring to the workplace. Diversity is an invaluable contributor to innovation and problem-solving success. As James Surowiecki shows in The Wisdom of Crowds, the more diverse the group in terms of expertise, gender, age, and background, the more ability the group has to avoid the problems of groupthink.James Surowiecki, The Wisdom of Crowds (New York: Anchor Books, 2005). Diversity helps company teams to come up with more creative and effective solutions. Teams whose members have complementary skills are often more successful because members can see one another’s blind spots. Diverse people will probably make different kinds of errors, which also means that they’ll be more likely to catch and correct each other’s mistakes.

Key Takeaways

- HRM is becoming increasingly important in organizations because today’s knowledge economy requires employees to contribute ideas and be engaged in executing the company’s strategy.

- HRM is becoming a strategic partner by identifying the skills that employees need and then providing employees with the training and structures needed to develop and deploy those competencies.

- All the elements of HRM—selection, placement, job design, and compensation—need to be aligned with the company’s strategy so that the right employees are hired for the right jobs and rewarded properly for their contributions to furthering the company’s goals.

Exercises

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- What are the advantages of the new SHRM approach?

- Name three elements of HRM.

- What must HRM do to be a true strategic partner of the company?

- What benefits does a diverse workforce provide the company?

- If you were an HR manager, what steps would you take to minimize the outsourcing of jobs in your department?

12.2 The Global War for Talent

Learning Objectives

- Define talent management.

- Discover how to attract the right workers to your organization.

- Understand the benefits of good talent management.

What Talent Management Means

You have likely heard the phrase “the war for talentThe competition between organizations to attract and retain the most able employees.,” which reflects competition among organizations to attract and retain the most able employees. For years, agencies that track demographic trends have been warning that the US workforce will shrink in the second and third decades of the twenty-first century as the baby boom generation (those born between 1945 and 1961) reaches retirement age. According to one source, there will be 11.5 million more jobs than workers in the United States by 2010.“Extreme Talent Shortage Makes Competition Fierce for Key Jobs and Highlights Needs for Leadership Development,” Business Wire, November 26, 2007, 27. Even though many boomers say they want (or have) to continue working past the traditional age of retirement, those who do retire or who leave decades-long careers to pursue “something I’ve always wanted to do” will force employers to scramble to replace well-trained, experienced workers. As workers compete for the most desirable jobs, employers will have to compete even more fiercely to find the right talent.

Peter Cappelli of the Wharton School defines talent managementAnticipating the need for human capital and setting a plan to meet it. as anticipating the need for human capital and setting a plan to meet it. Talent management goes hand in hand with succession planningA process whereby an organization ensures that employees are recruited and developed to fill each key role within the company., which refers to the process of recruiting and developing employees to ensure that the key roles in the company are filled.Peter Cappelli, “Talent Management for the Twenty-First Century,” Harvard Business Review 86, no. 3 (March 2008): 74–81. Most companies, unfortunately, don’t plan ahead for the talent they need, which means that they face shortages of critical skills at some times and surpluses at other times. Other companies use outdated methods of succession planning that don’t accurately forecast the skills they’ll need in the future.

Interestingly, however, techniques that were developed to achieve productivity breakthroughs in manufacturing can be applied to talent management. For example, it’s expensive to develop all talent internally; training people takes a long time and requires accurate predictions about which skills will be needed. Such predictions are increasingly difficult to make in our uncertain world. Therefore, rather than developing everyone internally, companies can hire from the outside when they need to tap specific skills. In manufacturing, this principle is known as “make or buy.” In human resources management (HRM), the solution is to make and buy—that is, to train some people and to hire others from the external marketplace. In this case, “making” an employee means hiring a person who doesn’t yet have all the needed skills to fulfill the role but who can be trained to develop them. The key to a successful “make” decision is to distinguish between the high-potential employees who don’t yet have the skills but who can learn them, from the mediocre employees who merely lack the skills. The “buy” decision means hiring an employee who has all the necessary skills and experience to fulfill the role from day one. The buy decision is useful when it’s too difficult to predict exactly which skills will be needed in the future.Patricia M. Buhler, “Managing in the New Millennium; Succession Planning: Not Just for the C Suite,” Supervision 69, no. 3 (2008): 19–23.

Ethics in Action

One month after launching in Kenya, start-up txteagle became one of the country’s largest employers with a workforce of 10,000 Kenyans.Kate Greene, “Crowd-Sourcing the World,” MIT Tech Review, January 21, 2009, accessed January 23, 2011, http://www.technologyreview.com/business/21983. Nathan Eagle founded txteagle in 2008. Txteagle deconstructs work into microtasks that can be performed on any simple mobile phone through texting. For example, one task is to type in local road signs (the data will be used to create a satellite navigation system).Robert Bain, “The Power of Text in the Developing World,” Research, January 20, 2011, accessed May 17, 2011, http://www.research-live.com/features/the-power-of-text-in-the-developing-world/4004395.article. Txteagle is similar to Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (mTurk), which also asks workers to complete microtasks such as clicking on photos that contain a particular object. The difference is that workers for txteagle only need a simple mobile phone—no computer or Internet access is necessary. Txteagle distributes the microtasks to thousands of workers (currently primarily in Africa) who complete them and get paid via the mobile phone either in airtime minutes or in cash through the M-Pesa service.Andrea Meyer, “Workforce Innovation: How Txteagle Distributes Microtasks Worldwide,” Working Knowledge (blog), January 23, 2011, accessed January 23, 2011, http://workingknowledge.com/blog/?p=1444; Jessica Vaughn, “Q&A: Nathan Eagle, Founder of txteagle,” JWT Intelligence, March 3, 2010, accessed January 23, 2011, http://www.jwtintelligence.com/2010/03/qa-nathan-eagle-founder-of-txteagle. “Txteagle is a commercial corporation that enables people to earn small amounts of money on their mobile phones by completing simple tasks for our corporate clients,” says Eagle.Jessica Vaughn, “Q&A: Nathan Eagle, Founder of txteagle,” JWT Intelligence, March 3, 2010, accessed January 23, 2011, http://www.jwtintelligence.com/2010/03/qa-nathan-eagle-founder-of-txteagle.

Txteagle now has partnerships with 220 mobile operators in more than eighty countries.“Mobile Work,” Economist, October 28, 2010, accessed January 23, 2011, http://www.economist.com/node/17366137. This expands txteagle ’s reach to 2.1 billion cell phone users in sub-Saharan Africa, Brazil, and India, who can all participate as workers.Txteagle website, accessed January 23, 2011, http://txteagle.com. Currently, the firm earns revenues in forty-nine countries. Companies like txteagle and mTurk give citizens in poor countries an opportunity to get work. But some Westerners criticize mTurk because employers can reject a person’s work without explanation. The pay scale is also very low—about twenty-four cents an hour, which makes some critics call mTurk a “digital sweatshop.”Bryan Walsh, “Pennies for Your Thoughts,” Time, January 31, 2011, accessed January 31, 2011,http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2043450,00.html. For workers in developing nations, however, where wages are low and unemployment rates are high, such wages may be better than the alternative of no work.

Another principle from manufacturing that works well in talent management is to run smaller batch sizes.Mason Carpenter, Talya Bauer, and Berrin Erdogan, Principles of Management (Nyack, NY: Flat World Knowledge, 2009), accessed January 5, 2011, http://www.flatworldknowledge.com/printed-book/127834. That is, rather than sending employees to three-year-long training programs, send them to shorter programs more frequently. With this approach, managers don’t have to make the training decision so far in advance. They can wait to decide exactly which skills employees will learn closer to the time the skill is needed, thereby ensuring that employees are trained on the skills they’ll actually use.

Attracting the Right Workers to the Organization

Winning the war for talent means more than simply attracting workers to your company. It means attracting the right workers—the ones who will be enthusiastic about their work. Enthusiasm for the job requires more than having a good attitude about receiving good pay and benefits—it means that an employee’s goals and aspirations also match those of the company. Therefore, it’s important to identify employees’ preferences and mutually assess how well they align with the company’s strategy. To do this, the organization must first be clear about the type of employee it wants. Companies already do this with customers—marketing executives identify specific segments of the universe of buyers to target for selling products. Red Bull, for example, targets college-age consumers, whereas Slim Fast goes for adults of all ages who are overweight. Both companies are selling beverages but to completely different consumer segments. Similarly, companies need to develop a profile of the type of workers they want to attract. Do you want entrepreneurial types who seek autonomy and continual learning, or do you want team players who enjoy collaboration, stability, and structure? Neither employee type is inherently “better,” but an employee who craves autonomy may feel constrained within the very same environment in which a team player would thrive.

As stated earlier, it’s important to “mutually assess” how well employees’ preferences align with the company’s strategy. Half of “mutual” refers to the company, but the other half refers to the job candidate. Potential employees need to know whether they’ll fit into the company well. One way to help prospective hires make this determination is to describe to them the “signature experience” that sets your company apart. As Tamara Erickson and Lynda Gratton define it, your company’s signature experience is the distinctive practice that shows what it’s really like to work at your company.Tamara J. Erickson and Lynda Gratton, “What It Means to Work Here,” Harvard Business Review 85, no. 3 (2007): 23–29.

Here are the signature experiences of two companies—Whole Foods Market and Goldman Sachs. At Whole Foods, team-based hiring is a signature experience—employees in each department vote on whether a new employee will be retained after a four-week trial period. This demonstrates to potential hires that Whole Foods is all about collaboration. In contrast, Goldman Sachs’s signature experience is multiple one-on-one interviews. The story often told to prospective hires is of the MBA student who went through sixty interviews before being hired. This story signals to new hires that they need to be comfortable meeting endless numbers of new people and building networks across the company. Those who enjoy meeting and being interviewed by so many diverse people are exactly the ones who will fit into Goldman’s culture.

The added benefit of hiring workers who match your organizational culture and are engaged in their work is that they will be less likely to leave your company just to get a higher salary.

Keeping Star Employees

The war for talent stems from the approaching shortage of workers. As mentioned earlier in this chapter, the millions of baby boomers reaching retirement age are leaving a gap in the US workforce. What’s more, workers are job-hopping more frequently than in the past. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average job tenure has dropped from fifteen years in 1980 to four years in 2007. As a manager, therefore, you need to give your employees reasons to stay with your company. One way to do this is to spend time talking with employees about their career goals. Listen to their likes and dislikes so that you can help them fully utilize the skills they like using or develop the new ones they wish to acquire.Beverly Kaye, Love ’Em or Lose ’Em (San Francisco: Barrett-Koehler, 2008).

Don’t be afraid to “grow” your employees. Some managers want to keep their employees in their department. They fear that helping employees grow on the job will mean that employees will outgrow their jobs and leave.Anne Field and Ken Gordon, “Do Your Stars See a Reason to Stay?,” Harvard Management Update 13, no. 6 (2008), http://hbr.org/product/do-your-stars-see-a-reason-to-stay/an/U0806A-PDF-ENG. However, keeping your employees down is a sure way to lose them. What’s more, if you help your employees advance, it’ll be easier for you to move up, because your employees will be better able to take on the role you leave behind.

In some cases, your employees may not be sure what career path they want. As a manager, you can help them identify their goals by asking questions such as the following:

- What assignments have you found most engaging?

- Which of your accomplishments in the last six months made you proudest?

- What makes for a great day at work?Timothy Butler, Getting Unstuck (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2007).

What Employees Want

Employees want to grow and develop, stretching their capabilities. They want projects that engage their heads as well as their hearts, and they want to connect with the people and things that will help them achieve their professional goals.Deloitte Research, It’s 2008: Do You Know Where Your Talent Is? Why Acquisition and Retention Strategies Don’t Work (Geneva, Switzerland: Deloitte Research Report, 2007), accessed May 10, 2011, http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-Venezuela/Local%20Assets/Documents/VE_Consulting_HC_connect_talentmgmt_Feb07.pdf. Here are two ways to provide this to your employees: First, connect people with mentors and help them build their networks. Research suggests that successful managers dedicate 70 percent more time to networking activities and 10 percent more time to communication than their less successful counterparts.Fred Luthans, Richard M. Yodgetts, and Stuart A. Rosenkrantz, Real Managers (Cambridge, MA: Ballinger, 1988). What makes networks special? Through networks, people energize one another as well as learn, create, and find new opportunities for growth. Second, help connect people with a sense of purpose. Focusing on the need for purpose is especially important for younger workers, who rank meaningful work and challenging experiences at the top of their job-search lists.Peter Sheahan, Generation Y: Thriving (and Surviving) with Generation Y at Work (Victoria, Australia: Hardie Grant Books, 2006).

Benefits of Good Talent Management

Global consulting firm McKinsey & Company conducted a study to identify a possible link between a company’s financial performance and its success in managing talent. The survey results, reported in May 2008, show that there was indeed a relationship between a firm’s financial performance and its global talent-management practices. Three talent-management practices, in particular, correlated highly with exceptional financial performance:

- Creating globally consistent talent-evaluation processes

- Achieving cultural diversity in a global setting

- Developing and managing global leaders“McKinsey Global-Talent-Management Survey of Over 450 Executives,” December 2007, as cited in Matthew Guthridge and Asmus B. Komm, “Why Multinationals Struggle to Manage Talent,” McKinsey Quarterly, May 2008, 19–25, accessed January 30, 2009, http://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/article_print.aspx?L2=18&L3=31&ar=2140.

The McKinsey survey found that companies achieving scores in the top third of any of these areas had a 70 percent chance of achieving financial performance in the top third of all companies.Matthew Guthridge and Asmus B. Komm, “Why Multinationals Struggle to Manage Talent,” McKinsey Quarterly, May 2008, 19–25.

Let’s take a closer look at what each of these three best practices entail. First, having consistent talent evaluation means that employees around the world are evaluated on the same standards. This is important because it means that if an employee from one country transfers to another, his or her manager can be assured that the employee has been held to the same level of skills and standards. Second, having cultural diversity means having employees who learn something about the culture of different countries, not just acquire language skills. This helps bring about open-mindedness across cultures. Finally, developing global leaders means rotating employees through different cultures, giving them international experience. Companies that do this best also have policies of giving managers incentives to share their employees with other units.

Key Takeaways

- The coming shortage of workers makes it imperative for managers to find, hire, retain, and develop their employees.

- Managers first need to define the skills that the company will need for the future. Then they can “make or buy”—that is, train or hire—employees with the needed skills.

- Retaining these employees requires engaging them on the job. Good talent-management practices translate into improved financial performance for the company as a whole.

Exercises

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- How might a manager go about identifying the skills that the company will need in the future?

- Describe the “make or buy” option and how it can be applied to human resources management.

- How would you go about attracting and recruiting talented workers to your organization? Suggest ideas you would use to retain stars and keep them happy in their jobs.

- What skills might an organization like a bank need from its employees?

12.3 Effective Selection and Placement Strategies

Learning Objectives

- Identify why a good job description benefits both the employer and the applicant.

- Learn how company culture can be used in selecting new employees.

- Know the advantages and disadvantages of personnel testing.

- Recognize some of the considerations in international staffing and placement.

Job-Description Best Practices

Selecting the right employees and placing them in the right positions within the company is a key human resources management (HRM) function and is vital to a company’s success. Companies should devote as much care and attention to this “soft” issue as they do to financial planning, because errors will have a financial impact and adverse effects on a company’s strategy.

Let’s use a hypothetical example of Walt, a manager in a midsize company who considers himself fortunate that the organizational chart allows him to have a full-time administrative assistant (AA) who reports to him. In the two years Walt has been in his job, however, five people have held this AA job. The most recent AA, who resigned after four weeks, told Walt that she hadn’t known what the job would involve. “I don’t do numbers; I’m not an accountant,” she said. “If you want someone to add up figures and do calculations all day, you should say so in the job description. Besides, I didn’t realize how long and stressful my commute would be—the traffic between here and my house is murder!”

Taken aback, Walt contacted the company’s HRM department to clarify the job description for the AA position. What he learned was that the description made available to applicants was, indeed, inadequate in a number of ways, which resulted in frequent turnover that was draining Walt’s company of resources that could be used for much more constructive purposes.

An accurate and complete job description is a powerful strategic human resources management (SHRM) tool that costs little to produce and can save a bundle in reduced turnover. While the realistic description may discourage some applicants (e.g., those who lack an affinity for calculations might not bother to apply for Walt’s AA position), those who follow through with the application process are much more likely to be satisfied with the job once hired. In addition to summarizing what the worker will actually be doing all day, here are some other suggestions for writing an effective job description:Mason Carpenter, Talya Bauer, and Berrin Erdogan, Principles of Management (Nyack, NY: Flat World Knowledge, 2009), accessed January 5, 2011, http://www.flatworldknowledge.com/printed-book/127834.

- List the job requirements in bullet form, so that job seekers can scan the posting quickly.

- Use common industry terms, which speak to knowledgeable job seekers.

- Avoid organization-specific terms and acronyms, which would confuse job seekers.

- Use meaningful job titles (not the internal job codes of the organization).

- Use key words taken from the list of common search terms (to maximize the chance that a job posting appears on a job seeker’s search).

- Include information about the organization, such as a short summary and links to more detailed information.

- Highlight special intangibles and unusual benefits of the job and workplace (e.g., flextime or travel).

- Specify the job’s location (and nearest large city) and provide links to local community pages (to entice job seekers with quality-of-life information).

Tailoring Recruitment to Match Company Culture

Managers who hire well don’t just hire for skills or academic background; they ask about the potential employee’s philosophy on life or how the candidate likes to spend free time. These questions help the manager assess whether the cultural fit is right. A company in which all work is done in teams needs team players, not just “A” students. Ask questions such as “Do you have a personal mission statement? If not, what would it be if you wrote one today?” to identify a potential hire’s preferences. Jeffrey Pfeffer, The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998).

At Google, for example, job candidates are asked questions such as “If you could change the world using Google’s resources, what would you build?”Chuck Slater, “The Faces and Voices of Google,” Fast Company, March 2008, 37–45. Google wants employees who will think and act on a grand scale—employees who will take on the challenges of their jobs, whatever their jobs may be. Take Josef DeSimone, Google’s executive chef. DeSimone, who’s worked everywhere from family-style restaurants to Michelin-caliber ones, was amazed to learn that Google had seventeen cafes for its employees. “Nobody changes the menu daily on this scale,” he says. “It’s unheard of.” When he was hired, DeSimone realized, “Wow, you hire a guy who’s an expert in food and let him run with it! You don’t get in his way or micromanage?”Chuck Slater, “Josef DeSimone—Executive Chef,” Fast Company, February 2008, 46–48. Google applies this approach to all positions; they let employees run with the challenge.

Traditionally, companies have built a competitive advantage by focusing on what they have—structural advantages such as economies of scale, a well-established brand, or dominance in certain market segments. Companies such as Southwest Airlines, by contrast, see its people as their advantage: “Our fares can be matched; our airplanes and routes can be copied. But we pride ourselves on our customer service,” said Sherry Phelps, director of corporate employment. That’s why Southwest looks for candidates who generate enthusiasm; they lean toward extroverted personalities. Southwest hires for attitude. Flight attendants have been known to sing the safety instructions, and pilots tell jokes over the public address system.

Pilots take pride in wearing the 2011 Adopt-A-Pilot program tie, an exclusive Southwest uniform piece designed by a fifth-grade student.

© 2011, Southwest Airlines. All rights reserved.

Southwest Airlines makes clear right from the start the kind of people it wants to hire. For example, one recruitment ad depicted Southwest cofounder Herb Kelleher dressed as Elvis and read “Work in a Place Where Elvis Has Been Spotted…The qualifications? It helps to be outgoing. Maybe even a bit off-center. And be prepared to stay awhile. After all, we have the lowest employee turnover rate in the industry.” People may scoff or question why Southwest indulges in such showy activities or wonder how an airline can treat its jobs so lightly. Phelps answers, “We do take our work seriously. It’s ourselves that we don’t.” People who don’t have a humane, can-do attitude are fired. Southwest has a probationary period during which it determines the compatibility of new hires with the culture. People may be excellent performers, but if they don’t match the culture, they’re let go. As Kelleher once said, “People will write me and complain, ‘Hey, I got terminated or put on probation for purely subjective reasons.’ And I’ll say, ‘Right! Those are the important reasons.’”Anne Bruce, “Southwest: Back to the FUNdamentals,” HR Focus 74, no. 3 (March 1997): 11; Kevin Freiberg and Jackie Freiberg, Nuts! Southwest Airlines’ Crazy Recipe for Business and Personal Success (Austin, TX: Bard, 2003); Roger Hallowell, “Southwest Airlines: A Case Study Linking Employee Needs Satisfaction and Organizational Capabilities to Competitive Advantage,” Human Resource Management 35, no. 4 (Winter 1996): 513–29; James L. Heskett and Roger Hallowell, “Southwest Airlines: 1993 (A),” Harvard Business School Case 694-023, 1993; “Southwest Airlines’ Herb Kelleher: Unorthodoxy at Work,” Management Review, January 1995, 2–9; Polly LaBarre, “Lighten Up! Blurring the Line Between Fun and Work Not Only Humanizes Organizations but Strengthens the Bottom Line,” Industry Week 245, no. 3 (February 5, 1996): 53–67; Kenneth Labich, “Is Herb Kelleher America’s Best CEO?,” Fortune, May 2, 1994, 44–45; Donald J. McNerney, “Employee Motivation: Creating a Motivated Workforce,” HR Focus 73, no. 8 (August 1996): 1; Richard Tomkins, “HR: The Seriously Funny Airline,” Financial Times, November 11, 1996, 14.

In many states, employees are covered under what is known as the at-will employment doctrineA doctrine that stipulates that a contract of employment can be terminated by either the employer or the employee at any time for any legal reason. (In the United States, for example, it is illegal to fire an employee on the basis of gender or ethnicity.). The at-will employment doctrine defines an employment relationship in which either party can break the relationship with no liability, provided there was no express contract for a definite term governing the employment relationship and that the employer doesn’t belong to a collective bargaining unit (i.e., a union).Mark A. Rothstein, Andria S. Knapp, and Lance Liebman, Cases and Materials on Employment Law (New York: Foundation Press, 1987), 738. However, there are legal restrictions on how purely subjective the reasons for firing can be. For instance, if the organization has written hiring and firing procedures and doesn’t follow them in selective cases, then those cases might give rise to claims of wrongful termination. Similarly, in situations where termination is clearly systematic—for example, based on age, race, religion, and so on—wrongful termination can be claimed.

Organized Labor and International Business

Many labor markets around the world have organized labor and labor unions, just as the United States does. Historically, most labor relations departments were decentralized, operating on the individual subsidiary level. With the rise of globalization, however, labor unions are seeing new threats, such as multinational enterprises (MNEs) threatening to move production to another country if the local union is demanding too much.

Because the actions of labor unions can constrain a firm’s ability to pursue an effective global strategy, the firm’s SHRM function must develop policies and practices that maintain harmony and reduce potential conflict between labor and management. Similarly, MNEs evaluate the labor climate when considering entering a new international location. MNEs typically look for labor markets that do not have a history of strife. MNEs may also try to negotiate better terms with a local union in exchange for locating a new facility in the country. To counter this, organized labor has attempted to organize globally, but this has proven to be difficult due to legal and cultural differences among countries.James Heskett, “What’s the Future of Globally Organized Labor?,” HBS Working Knowledge (blog), October 3, 2005, accessed January 31, 2011, http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/5029.html.

Tools and Methods: Interviewing and Testing

To make good selection and placement decisions, a company needs information about the job candidate. Testing and interviewing are two time-tested methods used to get that information.

A detailed interview begins by asking the candidate to describe his work history and then getting as much background on his most recent position (or the position most similar to the open position). Ask about the candidate’s responsibilities and major accomplishments. Then, ask in-depth questions about specific job situations. Called situational interviewsA job interview where the candidate is asked to describe in specific and behavioral detail how he would respond to a hypothetical situation., these types of interviews can focus on past experience or future situations. For example, experienced-based questions draw on the employees past performance. One such question may be “What is a major initiative you developed and the steps you took to get it adopted? Describe a problem you had with someone and how you handled it.” In contrast, future-oriented situation interview questions ask candidates to describe how they would handle a future hypothetical situation. An example of this kind of question is “Suppose you came up with a faster way to do a task, but your team was reluctant to make the change. What would you do in that situation?”

In addition to what is asked, it’s also important that interviewers understand what they should not ask, largely because certain questions lead to answers that may be used to discriminate. There are five particularly sensitive areas. First, the only times you can ask about age are when it is a requirement of a job duty or you need to determine whether a work permit is required. Second, it is rarely appropriate or legal to ask questions regarding race, color, national origin, or gender. Third, although candidates may volunteer religious or sexual orientation information in an interview, you still need to be careful not to discriminate. Ask questions that are relevant to work experience or qualifications. Fourth, firms cannot discriminate for health or disabilities; you may not ask about smoking habits, health-related issues, or disabilities in an interview. Finally, you may not ask questions about marital status, children, personal life, pregnancy, or arrest record. These kinds of questions could be tempting to ask if you’re interviewing for a position requiring travel; however, you can only explain the travel requirements and confirm that these requirements are acceptable.

In addition to interviews, many employers use testing to select and place job applicants. Any tests given to candidates must be job related and follow guidelines set forth by the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to be legal.Mason Carpenter, Talya Bauer, and Berrin Erdogan, Principles of Management (Nyack, NY: Flat World Knowledge, 2009), accessed January 5, 2011, http://www.flatworldknowledge.com/printed-book/127834. For the tests to be effective, they should be developed by reputable psychologists and administered by professionally qualified personnel who have had training in occupational testing in an industrial setting. The rationale behind testing is to give the employer more information before making the selection and placement decision—information vital to assessing how well a candidate is suited to a particular job. Most preemployment assessment tests measure thinking styles, behavioral traits, and occupational interests. The results are available almost immediately after a candidate completes the roughly hour-long questionnaire. Thinking-styles tests can tell the potential employer how fast someone can learn new things or how well she can verbally communicate. Behavioral-traits assessments measure energy level, assertiveness, sociability, manageability, and attitude. For example, a high sociability score would be a desirable trait for salespeople.Terri Mrosko, “The Personnel Puzzle: Preemployment Testing Can Help Your Bottom Line,” Inside Business 8, no. 8 (August 2006): 60–73.

International Staffing and Placement

In our increasingly global economy, managers need to decide between using expatriates or hiring locals when staffing international locations. An expatriateA person who is living in a country other than his or her home (native) country., or expat, is a person who is living in a country other than his or her home (native) country. Most expatriates only stay temporarily in the foreign country, planning to return to their home country. Some expatriates, however, never return to their country of citizenship. On the surface, this seems a simple choice between the firm-specific expertise of the expatriate and the cultural knowledge of the local hire. In reality, companies often fail to consider the high probability and high cost of expatriates failing to adapt and perform in their international assignments.

There are four predictors of a manager’s ability to succeed as an expatriate:

- Self-orientation. The expatriate has attributes that strengthen his or her self-esteem, self-confidence, and mental well-being.Mark Mendenhall and Gary Oddou, “The Dimensions of Expatriate Acculturation,” Academy of Management Review 10 (1985): 39–47.

- Others orientation. The expatriate has attributes that enhance his or her ability to interact effectively with host-country nationals (e.g., sociability and openness).Paula M. Caligiuri, “Selecting Expatriates for Personality Characteristics: A Moderating Effect of Personality on the Relationship between Host National Contact and Cross-cultural Adjustment,” Management International Review 40, no. 1 (2000): 65, accessed January 29, 2011, http://chrs.rutgers.edu/pub_documents/Paula_21.pdf.

- Perceptual ability. The expatriate has the ability to understand why people of other countries behave the way they do.Mark Mendenhall and Gary Oddou, “The Dimensions of Expatriate Acculturation,” Academy of Management Review 10 (1985): 39–47.

- Cultural toughness. The expatriate has the ability to adjust to a particular posting given the culture of the assignment’s country.J. Stewart Black, Mark Mendenhall, and Gary Oddou, “Toward a Comprehensive Model of International Adjustment: An Integration of Multiple Theoretical Perspectives,” Academy of Management Review 16, no. 2 (1991): 291–317.

Individuals who are high on all four dimensions are generally better able to cope and thrive with an expat experience. Research also shows that a global mind-set (i.e., having cognitive complexity—the ability to differentiate, articulate, and integrate—and a cosmopolitan outlook) greatly increases the chances that a global manager will be successful in international assignments.Joana S. Story, “Testing the Impact of Global Mindset on Positive Organizational Outcomes: A Multi-Level Analysis” (PhD diss., University of Nebraska at Lincoln, April 2010), accessed January 29, 2011, http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/aglecdiss/4; Mansour Javidan, “Bringing the Global Mindset to Leadership,” Harvard Business Review (blog), May 19, 2010, accessed January 29, 2011, http://blogs.hbr.org/imagining-the-future-of-leadership/2010/05/bringing-the-global-mindset-to.html. Ironically, however, studies show that most firms select expatriate managers on the basis of technical expertise and do not factor in a global mind-set.

Living and working in another place, such as São Paulo, Brazil, can be exciting, rewarding, and challenging.

© Thinkstock

Firms that use expatriates to staff international operations must be aware of and prepare for the possibility of expatriate failure, which means that the expatriate returns to the home country before completing the international assignment. Researchers estimate the expatriate failure rate to be 40 percent to 55 percent.J. Stewart Black, H. B. Gregersen, Mark Mendenhall, and L. K. Stroh, Globalizing People through International Assignments (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1999). For example, cultural issues can easily create misunderstandings between expatriate managers and employees, suppliers, customers, and local government officials. Given the high cost of expatriate failure, international-assignment decisions are often made too lightly in many companies. There are several factors that contribute to expatriate failure in US-headquartered multinational firms:

- The expatriate’s spouse is unable to adapt to a foreign culture, or there are other family-related reasons.

- The expatriate is unable to adjust to the new culture or lacks personal or emotional maturity to function well in the new country.

- The expatriate is unable to handle the larger overseas responsibilities.

The challenge is to overcome the natural tendency to hire a well-known, corporate insider over an unknown local at the international site. Here are some indications to consider in determining whether an expatriate or a local hire would be best.

Managers may want to choose an expatriate when the following factors are true:

- Company-specific technology or knowledge is important.

- Confidentiality in the staff position is an issue.

- There is a need for speed (i.e., assigning an expatriate is usually faster than hiring a local).

- Work rules regarding local workers are restrictive.

- The corporate strategy is focused on global integration.

Managers may want to staff the position with a local hire when the following factors are true:

- The need to interact with local customers, suppliers, employees, or officials is paramount.

- The corporate strategy is focused on multidomestic or market-oriented operations.

- Cost is an issue (i.e., expatriates often bring high relocation/travel costs).

- Immigration rules regarding foreign workers are restrictive.

- There are large cultural distances between the host country and candidate expatriates.Rebecca E. Weems, “Ethnocentric Staffing and International Assignments: A Transaction Cost Theory Approach” (presentation, Academy of Management Conference, San Diego, CA, August 9–12, 1998).

Key Takeaways

- Effective selection and placement means finding and hiring the right employees for your organization and then putting them into the jobs for which they are best suited. Providing an accurate and complete job description is a key step in the selection process.

- An important determination is whether the candidate’s personality is a good fit for the company’s culture. Interviewing is a common selection method. Situational interviews ask candidates to describe how they handled specific situations in the past (experience-based situational interviews) and how they would handle hypothetical questions in the future (future-oriented situational interviews). Other selection tools include cognitive tests, personality inventories, and behavioral-traits assessments. Specific personalities may be best suited for positions that require sales, teamwork, or entrepreneurship, respectively.

- In our increasingly global economy, managers need to decide between using expatriates and hiring locals when staffing international locations.

Exercises

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

- What kind of information would you include in a job description?

- Do you think it is important to hire employees who fit into the company culture? Why or why not?

- List questions that you would ask in a future-oriented situational interview.

- What requirements must personnel tests meet?

- If you were hiring to fill a position overseas, how would you go about selecting the best candidate?

12.4 The Roles of Pay Structure and Pay for Performance

Learning Objectives

- Explain the factors to be considered when setting pay levels.

- Understand the value of pay for performance plans.

- Discuss the challenges of individual versus team-based pay.

Compensation Design Issues for Global Firms

Pay can be thought of in terms of the “total reward” that includes an individual’s base salary, variable pay, share ownership, and other benefits. A bonusA form of variable pay where the employee earns additional compensation on the basis of achieved objectives., for example, is a form of variable pay. A bonus is a one-time cash payment, often awarded for exceptional performance. Providing employees with an annual statement of all the benefits they receive can help them understand the full value of what they are getting.Inez Anderson, “Human Resources: War or Revolution?,” Mondaq Business Briefing, August 1, 2007.

There are five areas that global firms must manage when designing their compensation strategy. The first involves setting up a worldwide compensation system. What this means is that the firm is coordinating each country’s compensation in such a way that the overall collection of countries operates as a system. Management, for instance, will have decided which features of the system to standardize and which ones to adapt to local customs, cultures, and practices. The second part of the strategy involves decisions about how to compensate third-country nationals. A third-country national (TCN)An individual who is a citizen of neither the US nor the host country and who is hired by the US government or a government-sanctioned contractor to perform work in the host country. is an individual who is a citizen of neither the United States nor the host country and who is hired by the US government or a government-sanctioned contractor to perform work in the host country. TCNs most often perform work on government contracts in the role of a private military contractor. The term can also be applied to foreign workers employed in private industry in the Arab Gulf region (e.g., Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia), in which it’s common to outsource work to noncitizens.