This is “Corporation: General Characteristics and Formation”, chapter 21 from the book Business and the Legal Environment (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 21 Corporation: General Characteristics and Formation

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should understand the following:

- The historical background of the corporation

- How partnerships compare with corporations

- What the corporation is as a legal entity, and how corporate owners can lose limited liability by certain actions

- How corporations are classified

The corporation is the dominant form of the business enterprise in the modern world. As a legal entity, it is bound by much of the law discussed in the preceding chapters. However, as a significant institutional actor in the business world, the corporation has a host of relationships that have called forth a separate body of law.

21.1 Historical Background

Learning Objectives

- Comprehend the historical significance of corporate formation.

- Learn about key court decisions and their effect on interstate commerce and corporate formation.

- Become acquainted with how states formed their corporate laws.

A Fixture of Every Major Legal System

Like partnership, the corporation is an ancient concept, recognized in the Code of Hammurabi, and to some degree a fixture in every other major legal system since then. The first corporations were not business enterprises; instead, they were associations for religious and governmental ends in which perpetual existence was a practical requirement. Thus until relatively late in legal history, kings, popes, and jurists assumed that corporations could be created only by political or ecclesiastical authority and that corporations were creatures of the state or church. By the seventeenth century, with feudalism on the wane and business enterprise becoming a growing force, kings extracted higher taxes and intervened more directly in the affairs of businesses by refusing to permit them to operate in corporate form except by royal grant. This came to be known as the concession theoryIncorporation was a concession given by royal grant of a sovereign., because incorporation was a concession from the sovereign.

The most important concessions, or charters, were those given to the giant foreign trading companies, including the Russia Company (1554), the British East India Company (1600), Hudson’s Bay Company (1670, and still operating in Canada under the name “the Bay”), and the South Sea Company (1711). These were joint-stock companiesCompanies in which stock or company funds are held jointly.—that is, individuals contributed capital to the enterprise, which traded on behalf of all the stockholders. Originally, trading companies were formed for single voyages, but the advantages of a continuing fund of capital soon became apparent. Also apparent was the legal characteristic that above all led shareholders to subscribe to the stock: limited liability. They risked only the cash they put in, not their personal fortunes.

Some companies were wildly successful. The British East India Company paid its original investors a fourfold return between 1683 and 1692. But perhaps nothing excited the imagination of the British more than the discovery of gold bullion aboard a Spanish shipwreck; 150 companies were quickly formed to salvage the sunken Spanish treasure. Though most of these companies were outright frauds, they ignited the search for easy wealth by a public unwary of the risks. In particular, the South Sea Company promised the sun and the moon: in return for a monopoly over the slave trade to the West Indies, it told an enthusiastic public that it would retire the public debt and make every person rich.

In 1720, a fervor gripped London that sent stock prices soaring. Beggars and earls alike speculated from January to August; and then the bubble burst. Without considering the ramifications, Parliament had enacted the highly restrictive Bubble Act, which was supposed to do away with unchartered joint-stock companies. When the government prosecuted four companies under the act for having fraudulently obtained charters, the public panicked and stock prices came tumbling down, resulting in history’s first modern financial crisis.

As a consequence, corporate development was severely retarded in England. Distrustful of the chartered company, Parliament issued few corporate charters, and then only for public or quasi-public undertakings, such as transportation, insurance, and banking enterprises. Corporation law languished: William Blackstone devoted less than 1 percent of his immensely influential Commentaries on the Law of England (1765) to corporations and omitted altogether any discussion of limited liability. In The Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith doubted that the use of corporations would spread. England did not repeal the Bubble Act until 1825, and then only because the value of true incorporation had become apparent from the experience of its former colonies.

US Corporation Formation

The United States remained largely unaffected by the Bubble Act. Incorporation was granted only by special acts of state legislatures, even well into the nineteenth century, but many such acts were passed. Before the Revolution, perhaps fewer than a dozen business corporations existed throughout the thirteen colonies. During the 1790s, two hundred businesses were incorporated, and their numbers swelled thereafter. The theory that incorporation should not be accomplished except through special legislation began to give way. As industrial development accelerated in the mid-1800s, it was possible in many states to incorporate by adhering to the requirements of a general statute. Indeed, by the late nineteenth century, all but three states constitutionally forbade their legislatures from chartering companies through special enactments.

The US Supreme Court contributed importantly to the development of corporate law. In Gibbons v. Ogden,Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. 1 (1824). a groundbreaking case, the Court held that the Commerce Clause of the US Constitution (Article I, Section 8, Clause 3) granted Congress the power to regulate interstate commerce. However, in Paul v. Virginia,Paul v. Virginia, 75 U.S. 168 (1868). the Court said that a state could prevent corporations not chartered there—that is, out-of-state or foreign corporationsA company incorporated outside the state in which it is doing business.—from engaging in what it considered the local, and not interstate, business of issuing insurance policies. The inference made by many was that states could not bar foreign corporations engaged in interstate business from their borders.

This decision brought about a competition in corporation laws. The early general laws had imposed numerous restrictions. The breadth of corporate enterprise was limited, ceilings were placed on total capital and indebtedness, incorporators were required to have residence in the state, the duration of the company often was not perpetual but was limited to a term of years or until a particular undertaking was completed, and the powers of management were circumscribed. These restrictions and limitations were thought to be necessary to protect the citizenry of the chartering legislature’s own state. But once it became clear that companies chartered in one state could operate in others, states began in effect to “sell” incorporation for tax revenues.

New Jersey led the way in 1875 with a general incorporation statute that greatly liberalized the powers of management and lifted many of the former restrictions. The Garden State was ultimately eclipsed by Delaware, which in 1899 enacted the most liberal corporation statute in the country, so that to the present day there are thousands of “Delaware corporations” that maintain no presence in the state other than an address on file with the secretary of state in Dover.

During the 1920s, the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws drafted a Uniform Business Corporation Act, the final version of which was released in 1928. It was not widely adopted, but it did provide the basis during the 1930s for revisions of some state laws, including those in California, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania. By that time, in the midst of the Great Depression, the federal government for the first time intruded into corporate law in a major way by creating federal agencies, most notably the Securities and Exchange Commission in 1934, with power to regulate the interstate issuance of corporate stock.

Corporate Law Today

Following World War II, most states revised their general corporation laws. A significant development for states was the preparation of the Model Business Corporation Act by the American Bar Association’s Committee on Corporate Laws. About half of the states have adopted all or major portions of the act. The 2005 version of this act, the Revised Model Business Corporation Act (RMBCA), will be referred to throughout our discussion of corporation law.

Key Takeaway

Corporations have their roots in political and religious authority. The concept of limited liability and visions of financial rewards fueled the popularity of joint-stock companies, particularly trading companies, in late-seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century England. The English Parliament successfully enacted the Bubble Act in 1720 to curb the formation of these companies; the restrictions weren’t loosened until over one hundred years later, after England viewed the success of corporations in its former colonies. Although early corporate laws in the United States were fairly restrictive, once states began to “sell” incorporation for tax revenues, the popularity of liberal and corporate-friendly laws caught on, especially in Delaware beginning in 1899. A corporation remains a creature of the state—that is, the state in which it is incorporated. Delaware remains the state of choice because more corporations are registered there than in any other state.

Exercises

- If the English Parliament had not enacted the Bubble Act in 1720, would the “bubble” have burst? If so, what would have been the consequences to corporate development?

- What were some of the key components of early US corporate laws? What was the rationale behind these laws?

- In your opinion, what are some of the liberal laws that attract corporations to Delaware?

21.2 Partnerships versus Corporations

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish basic aspects of partnership formation from those of corporate formation.

- Explain ownership and control in partnerships and in publicly held and closely held corporations.

- Know how partnerships and corporations are taxed.

Let us assume that three people have already formed a partnership to run a bookstore business. Bob has contributed $80,000. Carol has contributed a house in which the business can lawfully operate. Ted has contributed his services; he has been managing the bookstore, and the business is showing a slight profit. A friend has been telling them that they ought to incorporate. What are the major factors they should consider in reaching a decision?

Ease of Formation

Partnerships are easy to form. If the business is simple enough and the partners are few, the agreement need not even be written down. Creating a corporation is more complicated because formal documents must be placed on file with public authorities.

Ownership and Control

All general partners have equal rights in the management and conduct of the business. By contrast, ownership and control of corporations are, in theory, separated. In the publicly held corporationA firm that is traded publicly through the sale of stock subscriptions, has many shareholders and widely dispersed ownership, and in which shareholders have little control., which has many shareholders, the separation is real. Ownership is widely dispersed because millions of shares are outstanding and it is rare that any single shareholder will own more than a tiny percentage of stock. It is difficult under the best of circumstances for shareholders to exert any form of control over corporate operations. However, in the closely held corporationA corporation with few shareholders, so that separation of ownership and control may be less pronounced than in a publicly held corporation or even nonexistent., which has few shareholders, the officers or senior managers are usually also the shareholders, so the separation of ownership and control may be less pronounced or even nonexistent.

Transferability of Interests

Transferability of an interest in a partnership is a problem because a transferee cannot become a member unless all partners consent. The problem can be addressed and overcome in the partnership agreement. Transfer of interestTransferring an ownership interest through the sale of stock from one person to the next. in a corporation, through a sale of stock, is much easier; but for the stock of a small corporation, there might not be a market or there might be contractual restrictions on transfer.

Financing

Partners have considerable flexibility in financing. They can lure potential investors by offering interests in profits and, in the case of general partnerships, control. Corporations can finance by selling freely transferable stock to the public or by incurring debt. Different approaches to the financing of corporations are discussed in Chapter 22 "Legal Aspects of Corporate Finance".

Taxation

The partnership is a conduit for income and is not taxed as a separate entity. Individual partners are taxed, and although limited by the 1986 Tax Reform Act, they can deduct partnership losses. Corporate earnings, on the other hand, are subject to double taxation. The corporation is first taxed on its own earnings as an entity. Then, when profits are distributed to shareholders in the form of dividends, the shareholders are taxed again. (A small corporation, with no more than one hundred shareholders, can elect S corporation status. Because S corporations are taxed as partnerships, they avoid double taxation.) However, incorporating brings several tax benefits. For example, the corporation can take deductions for life, medical, and disability insurance coverage for its employees, whereas partners or sole proprietors cannot.

Key Takeaway

Partnerships are easier to form than corporations, especially since no documents are required. General partners share both ownership and control, but in publicly held corporations, these functions are separated. Additional benefits for a partnership include flexibility in financing, single taxation, and the ability to deduct losses. Transfer of interest in a partnership can be difficult if not addressed in the initial agreement, since all partners must consent to the transfer.

Exercises

- Provide an example of when it would be best to form a partnership, and cite the advantages and disadvantages of doing so.

- Provide an example of when it would be best to form a corporation, and cite the advantages and disadvantages of doing so.

21.3 The Corporate Veil: The Corporation as a Legal Entity

Learning Objectives

- Know what rights a corporate “person” and a natural person have in common.

- Recognize when a corporate “veil” is pierced and shareholder liability is imposed.

- Identify other instances when a shareholder will be held personally liable.

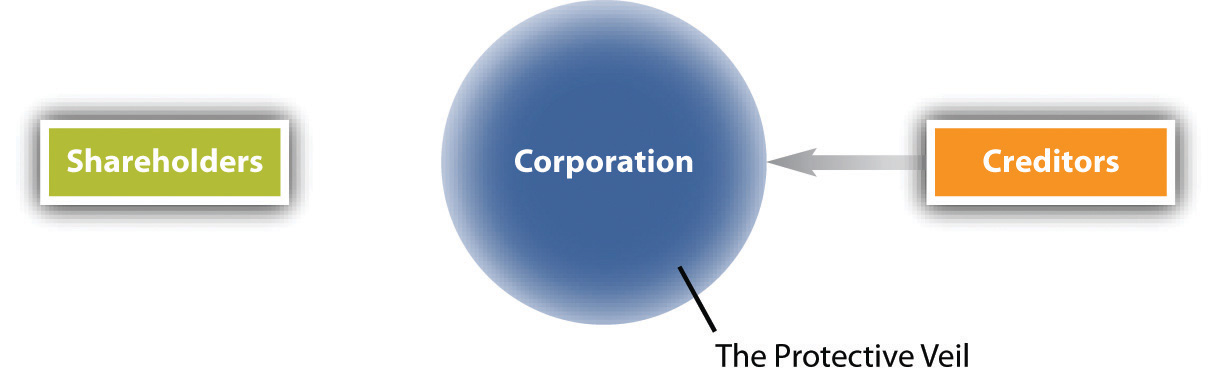

In comparing partnerships and corporations, there is one additional factor that ordinarily tips the balance in favor of incorporating: the corporation is a legal entity in its own right, one that can provide a “veil” that protects its shareholders from personal liability.

Figure 21.1 The Corporate Veil

This crucial factor accounts for the development of much of corporate law. Unlike the individual actor in the legal system, the corporation is difficult to deal with in conventional legal terms. The business of the sole proprietor and the sole proprietor herself are one and the same. When a sole proprietor makes a decision, she risks her own capital. When the managers of a corporation take a corporate action, they are risking the capital of others—the shareholders. Thus accountability is a major theme in the system of law constructed to cope with legal entities other than natural persons.

The Basic Rights of the Corporate “Person”

To say that a corporation is a “person”When corporations are granted the same rights as natural persons. does not automatically describe what its rights are, for the courts have not accorded the corporation every right guaranteed a natural person. Yet the Supreme Court recently affirmed in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010) that the government may not suppress the First Amendment right of political speech because the speaker is a corporation rather than a natural person. According to the Court, “No sufficient governmental interest justifies limits on the political speech of nonprofit or for-profit corporations.”Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. ___ (2010).

The courts have also concluded that corporations are entitled to the essential constitutional protections of due process and equal protection. They are also entitled to Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable search and seizure; in other words, the police must have a search warrant to enter corporate premises and look through files. Warrants, however, are not required for highly regulated industries, such as those involving liquor or guns. The Double Jeopardy Clause applies to criminal prosecutions of corporations: an acquittal cannot be appealed nor can the case be retried. For purposes of the federal courts’ diversity jurisdiction, a corporation is deemed to be a citizen of both the state in which it is incorporated and the state in which it has its principal place of business (often, the corporate “headquarters”).

Until relatively recently, few cases had tested the power of the state to limit the right of corporations to spend their own funds to speak the “corporate mind.” Most cases involving corporate free speech address advertising, and few states have enacted laws that directly impinge on the freedom of companies to advertise. But those states that have done so have usually sought to limit the ability of corporations to sway voters in public referenda. In 1978, the Supreme Court finally confronted the issue head on in First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti (Section 21.7.1 "Limiting a Corporation’s First Amendment Rights"). The ruling in Bellotti was reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. In Citizens United, the Court struck down the part of the McCain-Feingold ActThe Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA, McCain–Feingold Act, Pub.L. 107-155, 116 Stat. 81, enacted March 27, 2002, H.R. 2356). that prohibited all corporations, both for-profit and not-for-profit, and unions from broadcasting “electioneering communications.”

Absence of Rights

Corporations lack certain rights that natural persons possess. For example, corporations do not have the privilege against self-incrimination guaranteed for natural persons by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. In any legal proceeding, the courts may force a corporation to turn over incriminating documents, even if they also incriminate officers or employees of the corporation. As we explore in Chapter 25 "Corporate Expansion, State and Federal Regulation of Foreign Corporations, and Corporate Dissolution", corporations are not citizens under the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Constitution, so that the states can discriminate between domestic and foreign corporations. And the corporation is not entitled to federal review of state criminal convictions, as are many individuals.

Piercing the Corporate Veil

Given the importance of the corporate entity as a veil that limits shareholder liability, it is important to note that in certain circumstances, the courts may reach beyond the wall of protection that divides a corporation from the people or entities that exist behind it. This is known as piercing the corporate veilThe protection of the corporation (the veil) is set aside for litigation purposes, and liability can be imposed on individual shareholders or entities that exist behind the corporation., and it will occur in two instances: (1) when the corporation is used to commit a fraud or an injustice and (2) when the corporation does not act as if it were one.

Fraud

The Felsenthal Company burned to the ground. Its president, one of the company’s largest creditors and also virtually its sole owner, instigated the fire. The corporation sued the insurance company to recover the amount for which it was insured. According to the court in the Felsenthal case, “The general rule of law is that the willful burning of property by a stockholder in a corporation is not a defense against the collection of the insurance by the corporation, and…the corporation cannot be prevented from collecting the insurance because its agents willfully set fire to the property without the participation or authority of the corporation or of all of the stockholders of the corporation.”D. I. Felsenthal Co. v. Northern Assurance Co., Ltd., 284 Ill. 343, 120 N.E. 268 (1918). But because the fire was caused by the beneficial owner of “practically all” the stock, who also “has the absolute management of [the corporation’s] affairs and its property, and is its president,” the court refused to allow the company to recover the insurance money; allowing the company to recover would reward fraud.Felsenthal Co. v. Northern Assurance Co., Ltd., 120 N.E. 268 (Ill. 1918).

Failure to Act as a Corporation

In other limited circumstances, individual stockholders may also be found personally liable. Failure to follow corporate formalities, for example, may subject stockholders to personal liabilityA failure to follow corporate formalities—for example, inadequate capitalization or commingling of assets—can subject stockholders to personal liability.. This is a special risk that small, especially one-person, corporations run. Particular factors that bring this rule into play include inadequate capitalization, omission of regular meetings, failure to record minutes of meetings, failure to file annual reports, and commingling of corporate and personal assets. Where these factors exist, the courts may look through the corporate veil and pluck out the individual stockholder or stockholders to answer for a tort, contract breach, or the like. The classic case is the taxicab operator who incorporates several of his cabs separately and services them through still another corporation. If one of the cabs causes an accident, the corporation is usually “judgment proof” because the corporation will have few assets (practically worthless cab, minimum insurance). The courts frequently permit plaintiffs to proceed against the common owner on the grounds that the particular corporation was inadequately financed.

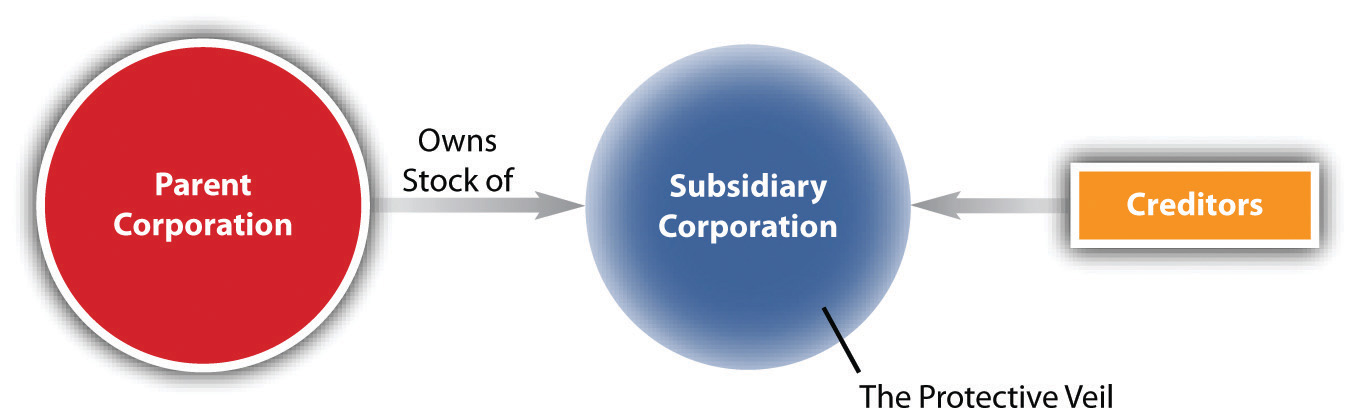

Figure 21.2 The Subsidiary as a Corporate Veil

When a corporation owns a subsidiary corporation, the question frequently arises whether the subsidiary is acting as an independent entity (see Figure 21.2 "The Subsidiary as a Corporate Veil"). The Supreme Court addressed this question of derivative versus direct liability of the corporate parent vis-à-vis its subsidiary in United States v. Bestfoods, (see Section 21.7.2 "Piercing the Corporate Veil").

Other Types of Personal Liability

Even when a corporation is formed for a proper purpose and is operated as a corporation, there are instances in which individual shareholders will be personally liable. For example, if a shareholder involved in company management commits a tort or enters into a contract in a personal capacity, he will remain personally liable for the consequences of his actions. In some states, statutes give employees special rights against shareholders. For example, a New York statute permits employees to recover wages, salaries, and debts owed them by the company from the ten largest shareholders of the corporation. (Shareholders of public companies whose stock is traded on a national exchange or over the counter are exempt.) Likewise, federal law permits the IRS to recover from the “responsible persons” any withholding taxes collected by a corporation but not actually paid over to the US Treasury.

Key Takeaway

Corporations have some of the legal rights of a natural person. They are entitled to the constitutional protections of due process and equal protection, Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable search and seizure, and First Amendment protection of free speech and expression. For purposes of the federal courts’ diversity jurisdiction, a corporation is deemed to be a citizen of both the state in which it is incorporated and the state in which it has its principal place of business. However, corporations do not have the privilege against self-incrimination guaranteed for natural persons by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Further, corporations are not free from liability. Courts will pierce the corporate veil and hold a corporation liable when the corporation is used to perpetrate fraud or when it fails to act as a corporation.

Exercises

- Do you think that corporations should have rights similar to those of natural persons? Should any of these rights be curtailed?

- What is an example of speaking the “corporate mind”?

- If Corporation BCD’s president and majority stockholder secretly sells all of his stock before resigning a few days later, and the corporation’s unexpected change in majority ownership causes the share price to plummet, do corporate stockholders have a cause of action? If so, under what theory?

21.4 Classifications of Corporations

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish the “public,” or municipal, corporation from the publicly held corporation.

- Explain how the tax structure for professional corporations evolved.

- Define the two types of business corporations.

Nonprofit Corporations

One of the four major classifications of corporations is the nonprofit corporationA corporation in which no part of the income is distributable to its members, directors, or officers. (also called not-for-profit corporation). It is defined in the American Bar Association’s Model Non-Profit Corporation Act as “a corporation no part of the income of which is distributable to its members, directors or officers.” Nonprofit corporations may be formed under this law for charitable, educational, civil, religious, social, and cultural purposes, among others.

Public Corporations

The true public corporation is a governmental entity. It is often called a municipal corporationA governmental entity; also called a public corporation., to distinguish it from the publicly held corporation, which is sometimes also referred to as a “public” corporation, although it is in fact private (i.e., it is not governmental). Major cities and counties, and many towns, villages, and special governmental units, such as sewer, transportation, and public utility authorities, are incorporated. These corporations are not organized for profit, do not have shareholders, and operate under different statutes than do business corporations.

Professional Corporations

Until the 1960s, lawyers, doctors, accountants, and other professionals could not practice their professions in corporate form. This inability, based on a fear of professionals’ being subject to the direction of the corporate owners, was financially disadvantageous. Under the federal income tax laws then in effect, corporations could establish far better pension plans than could the self-employed. During the 1960s, the states began to let professionals incorporate, but the IRS balked, denying them many tax benefits. In 1969, the IRS finally conceded that it would tax a professional corporationA corporation of lawyers, doctor, accountants, or other professionals who enjoy the same benefits in corporate form as do other corporations. just as it would any other corporation, so that professionals could, from that time on, place a much higher proportion of tax-deductible income into a tax-deferred pension. That decision led to a burgeoning number of professional corporations.

Business Corporations

The Two Types

It is the business corporationIn contrast to public (municipal), professional, or nonprofit corporations, business corporations are of two types: publicly held and closely held, referring to how the stock is held within the corporation. proper that we focus on in this unit. There are two broad types of business corporations: publicly held (or public) and closely held (or close or private) corporations. Again, both types are private in the sense that they are not governmental.

The publicly held corporation is one in which stock is widely held or available for wide public distribution through such means as trading on a national or regional stock exchange. Its managers, if they are also owners of stock, usually constitute a small percentage of the total number of shareholders and hold a small amount of stock relative to the total shares outstanding. Few, if any, shareholders of public corporations know their fellow shareholders.

By contrast, the shareholders of the closely held corporation are fewer in number. Shares in a closely held corporation could be held by one person, and usually by no more than thirty. Shareholders of the closely held corporation often share family ties or have some other association that permits each to know the others.

Though most closely held corporations are small, no economic or legal reason prevents them from being large. Some are huge, having annual sales of several billion dollars each. Roughly 90 percent of US corporations are closely held.

The giant publicly held companies with more than $1 billion in assets and sales, with initials such as IBM and GE, constitute an exclusive group. Publicly held corporations outside this elite class fall into two broad (nonlegal) categories: those that are quoted on stock exchanges and those whose stock is too widely dispersed to be called closely held but is not traded on exchanges.

Key Takeaway

There are four major classifications of corporations: (1) nonprofit, (2) municipal, (3) professional, and (4) business. Business corporations are divided into two types, publicly held and closely held corporations.

Exercises

- Why did professionals, such as doctors, lawyers, and accountants, wait so long to incorporate?

- Distinguish a publicly held corporation from a closely held one.

- Are most corporations in the US publicly or closely held? Are closely held corporations subject to different provisions than publicly held ones?

21.5 Corporate Organization

Learning Objectives

- Recognize the steps to issue a corporate charter.

- Know the states’ rights in modifying a corporate charter.

- Discuss factors to consider in selecting a state in which to incorporate.

- Explain the functions and liability of a promoter.

- Understand the business and legal requirements in executing and filing the articles of incorporation.

As discussed in Section 21.4 "Classifications of Corporations", corporate status offers companies many protections. If the owners of a business decide to incorporate after weighing the pros and cons of incorporation, they need to take the steps explained in this section.

The Corporate Charter

Function of the Charter

The ultimate goal of the incorporation process is issuance of a corporate charterThe basic document of incorporation filed in the appropriate public office, also referred to as articles of incorporation.. The term used for the document varies from state to state. Most states call the basic document filed in the appropriate public office the “articles of incorporation” or “certificate of incorporation,” but there are other variations. There is no legal significance to these differences in terminology.

Chartering is basically a state prerogative. Congress has chartered several enterprises, including national banks (under the National Banking Act), federal savings and loan associations, national farm loan associations, and the like, but virtually all business corporations are chartered at the state level.

Originally a legislative function, chartering is now an administrative function in every state. The secretary of state issues the final indorsement to the articles of incorporation, thus giving them legal effect.

Charter as a Contract

The charter is a contract between the state and the corporation. Under the Contracts Clause of Article I of the Constitution, no state can pass any law “impairing the obligation of contracts.” In 1816, the question arose whether a state could revoke or amend a corporate charter once granted. The corporation in question was Dartmouth College. The New Hampshire legislature sought to turn the venerable private college, operating under an old royal charter, into a public institution by changing the membership of its board. The case wound up in the Supreme Court. Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that the legislature’s attempt was unconstitutional, because to amend a charter is to impair a contract.Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U.S. 518 (1819).

This decision pleased incorporators because it implied that once a corporation had been created, the state could never modify the powers it had been granted. But, in addition, the ruling seemed to favor monopolies. The theory was that by granting a charter to, say, a railroad corporation, the state was barred from creating any further railroad corporations. Why? Because, the lawyers argued, a competitor would cut into the first company’s business, reducing the value of the charter, hence impairing the contract. Justice Joseph Story, concurring in the Dartmouth case, had already suggested the way out for the states: “If the legislature mean to claim such an authority [to alter or amend the charter], it must be reserved in the grant. The charter of Dartmouth College contains no such reservation.…” The states quickly picked up on Justice Story’s suggestion and wrote into the charter explicit language giving legislatures the authority to modify corporations’ charters at their pleasure. So the potential immutability of corporate charters had little practical chance to develop.

Selection of a State

Where to Charter

Choosing the particular venue in which to incorporate is the first critical decision to be made after deciding to incorporate. Some corporations, though headquartered in the United States, choose to incorporate offshore to take advantage of lenient taxation laws. Advantages of an offshore corporation include not only lenient tax laws but also a great deal of privacy as well as certain legal protections. For example, the names of the officers and directors can be excluded from documents filed. In the United States, over half of the Fortune 500 companies hold Delaware charters for reasons related to Delaware’s having a lower tax structure, a favorable business climate, and a legal system—both its statutes and its courts—seen as being up to date, flexible, and often probusiness. Delaware’s success has led other states to compete, and the political realities have caused the Revised Model Business Corporation Act (RMBCA), which was intentionally drafted to balance the interests of all significant groups (management, shareholders, and the public), to be revised from time to time so that it is more permissive from the perspective of management.

Why Choose Delaware?

Delaware remains the most popular state in which to incorporate for several reasons, including the following: (1) low incorporation fees; (2) only one person is needed to serve the incorporator of the corporation; the RMBC requires three incorporators; (3) no minimum capital requirement; (4) favorable tax climate, including no sales tax; (5) no taxation of shares held by nonresidents; and (5) no corporate income tax for companies doing business outside of Delaware. In addition, Delaware’s Court of Chancery, a court of equity, is renowned as a premier business court with a well-established body of corporate law, thereby affording a business a certain degree of predictability in judicial decision making.

The Promoter

Functions

Once the state of incorporation has been selected, it is time for promotersAn individual who takes the initial steps needed to form a corporation., the midwives of the enterprise, to go to work. Promoters are the individuals who take the steps necessary to form the corporation, and they often will receive stock in exchange for their efforts. They have four principal functions: (1) to seek out or discover business opportunities, (2) to raise capital by persuading investors to sign stock subscriptions, (3) to enter into contracts on behalf of the corporation to be formed, (4) and to prepare the articles of incorporation.

Promoters have acquired an unsavory reputation as fast talkers who cajole investors out of their money. Though some promoters fit this image, it is vastly overstated. Promotion is difficult work often carried out by the same individuals who will manage the business.

Contract Liability

Promoters face two major legal problems. First, they face possible liability on contracts made on behalf of the business before it is incorporated. For example, suppose Bob is acting as promoter of the proposed BCT Bookstore, Inc. On September 15, he enters into a contract with Computogram Products to purchase computer equipment for the corporation to be formed. If the incorporation never takes place, or if the corporation is formed but the corporation refuses to accept the contract, Bob remains liable.

Now assume that the corporation is formed on October 15, and on October 18 it formally accepts all the contracts that Bob signed prior to October 15. Does Bob remain liable? In most states, he does. The ratification theory of agency law will not help in many states that adhere strictly to agency rules, because there was no principal (the corporation) in existence when the contract was made and hence the promoter must remain liable. To avoid this result, Bob should seek an express novation, although in some states, a novation will be implied. The intention of the parties should be stated as precisely as possible in the contract, as the promoters learned in RKO-Stanley Warner Theatres, Inc. v. Graziano, (see Section 21.7.3 "Corporate Promoter").

The promoters’ other major legal concern is the duty owed to the corporation. The law is clear that promoters owe a fiduciary duty. For example, a promoter who transfers real estate worth $250,000 to the corporation in exchange for $750,000 worth of stock would be liable for $500,000 for breach of fiduciary duty.

Preincorporation Stock Subscriptions

One of the promoter’s jobs is to obtain preincorporation stock subscriptionsOffers by would-be investors to purchase stock in a corporation that is not as yet formed. to line up offers by would-be investors to purchase stock in the corporation to be formed. These stock subscriptions are agreements to purchase, at a specified price, a certain number of shares of stock of a corporation, which is to be formed at some point in the future. The contract, however, actually comes into existence after formation, once the corporation itself accepts the offer to subscribe. Alice agrees with Bob to invest $10,000 in the BCT Bookstore, Inc. for one thousand shares. The agreement is treated as an offer to purchase. The offer is deemed accepted at the moment the bookstore is incorporated.

The major problem for the corporation is an attempt by subscribers to revoke their offers. A basic rule of contract law is that offers are revocable before acceptance. Under RMBCA, Section 6.20, however, a subscription for shares is irrevocable for six months unless the subscription agreement itself provides otherwise or unless all the subscribers consent to revocation. In many states that have not adopted the model act, the contract rule applies and the offer is always revocable. Other states use various common-law devices to prevent revocation. For example, the subscription by one investor is held as consideration for the subscription of another, so that a binding contract has been formed.

Execution and Filing of the Articles of Incorporation

Once the business details are settled, the promoters, now known as incorporators, must sign and deliver the articles of incorporation to the secretary of state. The articles of incorporation typically include the following: the corporate name; the address of the corporation’s initial registered office; the period of the corporation’s duration (usually perpetual); the company’s purposes; the total number of shares, the classes into which they are divided, and the par value of each; the limitations and rights of each class of shareholders; the authority of the directors to establish preferred or special classes of stock; provisions for preemptive rights; provisions for the regulation of the internal affairs of the corporation, including any provision restricting the transfer of shares; the number of directors constituting the initial board of directors and the names and addresses of initial members; and the name and address of each incorporator. Although compliance with these requirements is largely a matter of filling in the blanks, two points deserve mention.

First, the choice of a name is often critical to the business. Under RMBCA, Section 4.01, the name must include one of the following words (or abbreviations): corporation, company, incorporated, or limited (Corp., Co., Inc., or Ltd.). The name is not allowed to deceive the public about the corporation’s purposes, nor may it be the same as that of any other company incorporated or authorized to do business in the state.

These legal requirements are obvious; the business requirements are much harder. If the name is not descriptive of the business or does not anticipate changes in the business, it may have to be changed, and the change can be expensive. For example, when Standard Oil Company of New Jersey changed its name to Exxon in 1972, the estimated cost was over $100 million. (And even with this expenditure, some shareholders grumbled that the new name sounded like a laxative.)

The second point to bear in mind about the articles of incorporation is that drafting the clause stating corporate purposes requires special care, because the corporation will be limited to the purposes set forth. In one famous case, the charter of Cornell University placed a limit on the amount of contributions it could receive from any one benefactor. When Jennie McGraw died in 1881, leaving to Cornell the carillon that still plays on the Ithaca, New York, campus to this day, she also bequeathed to the university her residuary estate valued at more than $1 million. This sum was greater than the ceiling placed in Cornell’s charter. After lengthy litigation, the university lost in the US Supreme Court, and the money went to her family.Cornell University v. Fiske, 136 U.S. 152 (1890). The dilemma is how to draft a clause general enough to allow the corporation to expand, yet specific enough to prevent it from engaging in undesirable activities.

Some states require the purpose clauses to be specific, but the usual approach is to permit a broad statement of purposes. Section 3.01 of the RMBCA goes one step further in providing that a corporation automatically “has the purpose of engaging in any lawful business” unless the articles specify a more limited purpose. Once completed, the articles of incorporation are delivered to the secretary of state for filing. The existence of a corporation begins once the articles have been filed.

Organizational Meeting of Directors

The first order of business, once the certificate of incorporation is issued, is a meeting of the board of directors named in the articles of incorporation. They must adopt bylaws, elect officers, and transact any other business that may come before the meeting (RMBCA, Section 2.05). Other business would include accepting (ratifying) promoters’ contracts, calling for the payment of stock subscriptions, and adopting bank resolution forms, giving authority to various officers to sign checks drawn on the corporation.

Section 10.20 of the RMBCA vests in the directors the power to alter, amend, or repeal the bylaws adopted at the initial meeting, subject to repeal or change by the shareholders. The articles of incorporation may reserve the power to modify or repeal exclusively to the shareholders. The bylaws may contain any provisions that do not conflict with the articles of incorporation or the law of the state.

Typical provisions in the bylaws include fixing the place and time at which annual stockholders’ meetings will be held, fixing a quorum, setting the method of voting, establishing the method of choosing directors, creating committees of directors, setting down the method by which board meetings may be called and the voting procedures to be followed, determining the offices to be filled by the directors and the powers with which each officer shall be vested, fixing the method of declaring dividends, establishing a fiscal year, setting out rules governing issuance and transfer of stock, and establishing the method of amending the bylaws.

Section 2.07 of the RMBCA provides that the directors may adopt bylaws that will operate during an emergency. An emergency is a situation in which “a quorum of the corporation’s directors cannot readily be assembled because of some catastrophic event.”

Key Takeaway

Articles of incorporation represent a corporate charter—that is, a contract between the corporation and the state. Filing these articles, or “chartering,” is accomplished at the state level. The secretary of state’s final approval gives these articles legal effect. A state cannot change a charter unless it reserves the right when granting the charter.

In selecting a state in which to incorporate, a corporation looks for a favorable corporate climate. Delaware remains the state of choice for incorporation, particularly for publicly held companies. Most closely held companies choose to incorporate in their home states.

Following the state selection, the promoter commences his or her functions, which include entering into contracts on behalf of the corporation to be formed (for which he or she can be held liable) and preparing the articles of incorporation.

The articles of incorporation must include the corporation’s name and its corporate purpose, which can be broad. Finally, once the certificate of incorporation is issued, the corporation’s board of directors must hold an organizational meeting.

Exercises

- Does the Contracts Clause of the Constitution, which forbids a state from impeding a contract, apply to corporations?

- What are some of the advantages of selecting Delaware as the state of incorporation?

- What are some of the risks that a promoter faces for his or her actions on behalf of the corporation? Can he or she limit these risks?

- What are the dangers of limiting a corporation’s purpose?

- What is the order of business at the first board of directors’ meeting?

21.6 Effect of Organization

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between a de jure and a de facto corporation.

- Define the doctrine of corporation by estoppel.

De Jure and De Facto Corporations

If promoters meet the requirements of corporate formation, a de jure corporationA corporation that exists in law, having met all of the necessary legal requirements., considered a legal entity, is formed. Because the various steps are complex, the formal prerequisites are not always met. Suppose that a company, thinking its incorporation has taken place when in fact it hasn’t met all requirements, starts up its business. What then? Is everything it does null and void? If three conditions exist, a court might decide that a de facto corporationA corporation that exists in fact, though it has not met all of the necessary legal requirements. has been formed; that is, the business will be recognized as a corporation. The state then has the power to force the de facto corporation to correct the defect(s) so that a de jure corporation will be created.

The three traditional conditions are the following: (1) a statute must exist under which the corporation could have been validly incorporated, (2) the promoters must have made a bona fide attempt to comply with the statute, and (3) corporate powers must have been used or exercised.

A frequent cause of defective incorporation is the promoters’ failure to file the articles of incorporation in the appropriate public office. The states are split on whether a de facto corporation results if every other legal requirement is met.

Corporation by Estoppel

Even if the incorporators omit important steps, it is still possible for a court, under estoppel principles, to treat the business as a corporation. Assume that Bob, Carol, and Ted have sought to incorporate the BCT Bookstore, Inc., but have failed to file the articles of incorporation. At the initial directors’ meeting, Carol turns over to the corporation a deed to her property. A month later, Bob discovers the omission and hurriedly submits the articles of incorporation to the appropriate public office. Carol decides she wants her land back. It is clear that the corporation was not de jure at the time she surrendered her deed, and it was probably not de facto either. Can she recover the land? Under equitable principles, the answer is no. She is estopped from denying the existence of the corporation, because it would be inequitable to permit one who has conducted herself as though there were a corporation to deny its existence in order to defeat a contract into which she willingly entered. As Cranson v. International Business Machines Corp. indicates (Section 21.7.4 "De Jure and De Facto Corporations"), the doctrine of corporation by estoppelUse of the equitable principle of estoppel by a court to treat a business as a corporation. can also be used by the corporation against one of its creditors.

Key Takeaway

A court will find that a corporation might exist under fact (de facto), and not under law (de jure) if the following conditions are met: (1) a statute exists under which the corporation could have been validly incorporated, (2) the promoters must have made a bona fide attempt to comply with the statute, and (3) corporate powers must have been used or exercised. A de facto corporation may also be found when a promoter fails to file the articles of incorporation. In the alternative, the court may look to estoppel principles to find a corporation.

Exercises

- What are some of the formal prerequisites to forming a de jure corporation?

- Are states in agreement over what represents a de facto corporation if a promoter fails to file the articles of incorporation?

- What is the rationale for corporation by estoppel?

21.7 Cases

Limiting a Corporation’s First Amendment Rights

First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti

435 U.S. 765 (1978)

MR. JUSTICE POWELL delivered the opinion of the Court.

In sustaining a state criminal statute that forbids certain expenditures by banks and business corporations for the purpose of influencing the vote on referendum proposals, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that the First Amendment rights of a corporation are limited to issues that materially affect its business, property, or assets. The court rejected appellants’ claim that the statute abridges freedom of speech in violation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments. The issue presented in this context is one of first impression in this Court. We postponed the question of jurisdiction to our consideration of the merits. We now reverse.

The statute at issue, Mass. Gen. Laws Ann., Ch. 55, § 8 (West Supp. 1977), prohibits appellants, two national banking associations and three business corporations, from making contributions or expenditures “for the purpose of…influencing or affecting the vote on any question submitted to the voters, other than one materially affecting any of the property, business or assets of the corporation.” The statute further specifies that “[no] question submitted to the voters solely concerning the taxation of the income, property or transactions of individuals shall be deemed materially to affect the property, business or assets of the corporation.” A corporation that violates § 8 may receive a maximum fine of $50,000; a corporate officer, director, or agent who violates the section may receive a maximum fine of $10,000 or imprisonment for up to one year, or both. Appellants wanted to spend money to publicize their views on a proposed constitutional amendment that was to be submitted to the voters as a ballot question at a general election on November 2, 1976. The amendment would have permitted the legislature to impose a graduated tax on the income of individuals. After appellee, the Attorney General of Massachusetts, informed appellants that he intended to enforce § 8 against them, they brought this action seeking to have the statute declared unconstitutional.

The court below framed the principal question in this case as whether and to what extent corporations have First Amendment rights. We believe that the court posed the wrong question. The Constitution often protects interests broader than those of the party seeking their vindication. The First Amendment, in particular, serves significant societal interests. The proper question therefore is not whether corporations “have” First Amendment rights and, if so, whether they are coextensive with those of natural persons. Instead, the question must be whether § 8 abridges expression that the First Amendment was meant to protect. We hold that it does. The speech proposed by appellants is at the heart of the First Amendment’s protection.

The freedom of speech and of the press guaranteed by the Constitution embraces at the least the liberty to discuss publicly and truthfully all matters of public concern without previous restraint or fear of subsequent punishment. Freedom of discussion, if it would fulfill its historic function in this nation, must embrace all issues about which information is needed or appropriate to enable the members of society to cope with the exigencies of their period. Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88, 101-102 (1940).

The referendum issue that appellants wish to address falls squarely within this description. In appellants’ view, the enactment of a graduated personal income tax, as proposed to be authorized by constitutional amendment, would have a seriously adverse effect on the economy of the State. The importance of the referendum issue to the people and government of Massachusetts is not disputed. Its merits, however, are the subject of sharp disagreement.

We thus find no support in the First or Fourteenth Amendment, or in the decisions of this Court, for the proposition that speech that otherwise would be within the protection of the First Amendment loses that protection simply because its source is a corporation that cannot prove, to the satisfaction of a court, a material effect on its business or property. The “materially affecting” requirement is not an identification of the boundaries of corporate speech etched by the Constitution itself. Rather, it amounts to an impermissible legislative prohibition of speech based on the identity of the interests that spokesmen may represent in public debate over controversial issues and a requirement that the speaker have a sufficiently great interest in the subject to justify communication.

Section 8 permits a corporation to communicate to the public its views on certain referendum subjects—those materially affecting its business—but not others. It also singles out one kind of ballot question—individual taxation as a subject about which corporations may never make their ideas public. The legislature has drawn the line between permissible and impermissible speech according to whether there is a sufficient nexus, as defined by the legislature, between the issue presented to the voters and the business interests of the speaker.

In the realm of protected speech, the legislature is constitutionally disqualified from dictating the subjects about which persons may speak and the speakers who may address a public issue. If a legislature may direct business corporations to “stick to business,” it also may limit other corporations—religious, charitable, or civic—to their respective “business” when addressing the public. Such power in government to channel the expression of views is unacceptable under the First Amendment. Especially where, as here, the legislature’s suppression of speech suggests an attempt to give one side of a debatable public question an advantage in expressing its views to the people, the First Amendment is plainly offended.

Because that portion of § 8 challenged by appellants prohibits protected speech in a manner unjustified by a compelling state interest, it must be invalidated. The judgment of the Supreme Judicial Court is reversed.

Case Questions

- According to the court, does § 8 abridge a freedom that the First Amendment is intended to protect? If so, which freedom(s)?

- Must a corporation prove a material effect on its business or property to maintain protection under the First Amendment?

- Can a state legislature dictate the subjects on which a corporation may “speak”?

Piercing the Corporate Veil

United States v. Bestfoods

113 F.3d 572 (1998)

SOUTER, JUSTICE

The United States brought this action under §107(a)(2) of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA) against, among others, respondent CPC International, Inc., the parent corporation of the defunct Ott Chemical Co. (Ott II), for the costs of cleaning up industrial waste generated by Ott II’s chemical plant. Section 107(a)(2) authorizes suits against, among others, “any person who at the time of disposal of any hazardous substance owned or operated any facility.” The trial focused on whether CPC, as a parent corporation, had “owned or operated” Ott II’s plant within the meaning of §107(a)(2). The District Court said that operator liability may attach to a parent corporation both indirectly, when the corporate veil can be pierced under state law, and directly, when the parent has exerted power or influence over its subsidiary by actively participating in, and exercising control over, the subsidiary’s business during a period of hazardous waste disposal. Applying that test, the court held CPC liable because CPC had selected Ott II’s board of directors and populated its executive ranks with CPC officials, and another CPC official had played a significant role in shaping Ott II’s environmental compliance policy.

The Sixth Circuit reversed. Although recognizing that a parent company might be held directly liable under §107(a)(2) if it actually operated its subsidiary’s facility in the stead of the subsidiary, or alongside of it as a joint venturer, that court refused to go further. Rejecting the District Court’s analysis, the Sixth Circuit explained that a parent corporation’s liability for operating a facility ostensibly operated by its subsidiary depends on whether the degree to which the parent controls the subsidiary and the extent and manner of its involvement with the facility amount to the abuse of the corporate form that will warrant piercing the corporate veil and disregarding the separate corporate entities of the parent and subsidiary. Applying Michigan veil-piercing law, the court decided that CPC was not liable for controlling Ott II’s actions, since the two corporations maintained separate personalities and CPC did not utilize the subsidiary form to perpetrate fraud or subvert justice.

Held:

1. When (but only when) the corporate veil may be pierced, a parent corporation may be charged with derivative CERCLA liability for its subsidiary’s actions in operating a polluting facility. It is a general principle of corporate law that a parent corporation (so-called because of control through ownership of another corporation’s stock) is not liable for the acts of its subsidiaries. CERCLA does not purport to reject this bedrock principle, and the Government has indeed made no claim that a corporate parent is liable as an owner or an operator under §107(a)(2) simply because its subsidiary owns or operates a polluting facility. But there is an equally fundamental principle of corporate law, applicable to the parent-subsidiary relationship as well as generally, that the corporate veil may be pierced and the shareholder held liable for the corporation’s conduct when, inter alia, the corporate form would otherwise be misused to accomplish certain wrongful purposes, most notably fraud, on the shareholder’s behalf. CERCLA does not purport to rewrite this well-settled rule, either, and against this venerable common-law backdrop, the congressional silence is audible. Cf. Edmonds v. Compagnie Generale Transatlantique, 443 U.S. 256, 266-267. CERCLA’s failure to speak to a matter as fundamental as the liability implications of corporate ownership demands application of the rule that, to abrogate a common-law principle, a statute must speak directly to the question addressed by the common law. United States v. Texas, 507 U.S. 529, 534.

2. A corporate parent that actively participated in, and exercised control over, the operations of its subsidiary’s facility may be held directly liable in its own right under §107(a)(2) as an operator of the facility.

(a) Derivative liability aside, CERCLA does not bar a parent corporation from direct liability for its own actions. Under the plain language of §107(a)(2), any person who operates a polluting facility is directly liable for the costs of cleaning up the pollution, and this is so even if that person is the parent corporation of the facility’s owner. Because the statute does not define the term “operate,” however, it is difficult to define actions sufficient to constitute direct parental “operation.” In the organizational sense obviously intended by CERCLA, to “operate” a facility ordinarily means to direct the workings of, manage, or conduct the affairs of the facility. To sharpen the definition for purposes of CERCLA’s concern with environmental contamination, an operator must manage, direct, or conduct operations specifically related to the leakage or disposal of hazardous waste, or decisions about compliance with environmental regulations.

(b) The Sixth Circuit correctly rejected the direct liability analysis of the District Court, which mistakenly focused on the relationship between parent and subsidiary, and premised liability on little more than CPC’s ownership of Ott II and its majority control over Ott II’s board of directors. Because direct liability for the parent’s operation of the facility must be kept distinct from derivative liability for the subsidiary’s operation of the facility, the analysis should instead have focused on the relationship between CPC and the facility itself, i.e., on whether CPC “operated” the facility, as evidenced by its direct participation in the facility’s activities. That error was compounded by the District Court’s erroneous assumption that actions of the joint officers and directors were necessarily attributable to CPC, rather than Ott II, contrary to time-honored common-law principles. The District Court’s focus on the relationship between parent and subsidiary (rather than parent and facility), combined with its automatic attribution of the actions of dual officers and directors to CPC, erroneously, even if unintentionally, treated CERCLA as though it displaced or fundamentally altered common-law standards of limited liability. The District Court’s analysis created what is in essence a relaxed, CERCLA-specific rule of derivative liability that would banish traditional standards and expectations from the law of CERCLA liability. Such a rule does not arise from congressional silence, and CERCLA’s silence is dispositive.

(c) Nonetheless, the Sixth Circuit erred in limiting direct liability under CERCLA to a parent’s sole or joint venture operation, so as to eliminate any possible finding that CPC is liable as an operator on the facts of this case. The ordinary meaning of the word “operate” in the organizational sense is not limited to those two parental actions, but extends also to situations in which, e.g., joint officers or directors conduct the affairs of the facility on behalf of the parent, or agents of the parent with no position in the subsidiary manage or direct activities at the subsidiary’s facility. Norms of corporate behavior (undisturbed by any CERCLA provision) are crucial reference points, both for determining whether a dual officer or director has served the parent in conducting operations at the facility, and for distinguishing a parental officer’s oversight of a subsidiary from his control over the operation of the subsidiary’s facility. There is, in fact, some evidence that an agent of CPC alone engaged in activities at Ott II’s plant that were eccentric under accepted norms of parental oversight of a subsidiary’s facility: The District Court’s opinion speaks of such an agent who played a conspicuous part in dealing with the toxic risks emanating from the plant’s operation. The findings in this regard are enough to raise an issue of CPC’s operation of the facility, though this Court draws no ultimate conclusion, leaving the issue for the lower courts to reevaluate and resolve in the first instance.

113 F.3d 572, vacated and remanded.

Case Questions

- In what ways can operator liability attach to a parent corporation? How did the Sixth Circuit Court disagree with the district court’s analysis?

- Is direct liability for a parent company’s operation of the facility distinct from derivative liability for the subsidiary’s operation of the facility? Should the focus be on parent and subsidiary or on parent and facility?

- What norms of corporate behavior does the court look to in determining whether an officer or a director is involved in the operation of a facility?

Corporate Promoter

RKO-Stanley Warner Theatres, Inc. v. Graziano

355 A.2d. 830 (1976)

EAGEN, JUSTICE.

On April 30, 1970, RKO-Stanley Warner Theatres, Inc. [RKO], as seller, entered into an agreement of sale with Jack Jenofsky and Ralph Graziano, as purchasers. This agreement contemplated the sale of the Kent Theatre, a parcel of improved commercial real estate located at Cumberland and Kensington Avenues in Philadelphia, for a total purchase price of $70,000. Settlement was originally scheduled for September 30, 1970, and, at the request of Jenofsky and Graziano, continued twice, first to October 16, 1970, and then to October 21, 1970. However, Jenofsky and Graziano failed to complete settlement on the last scheduled date.

Subsequently, on November 13, 1970, RKO filed a complaint in equity seeking judicial enforcement of the agreement of sale. Although Jenofsky, in his answer to the complaint, denied personal liability for the performance of the agreement, the chancellor, after a hearing, entered a decree nisi granting the requested relief sought by RKO.…This appeal ensued.

At the time of the execution of this agreement, Jenofsky and Graziano were engaged in promoting the formation of a corporation to be known as Kent Enterprises, Inc. Reflecting these efforts, Paragraph 19 of the agreement, added by counsel for Jenofsky and Graziano, recited:

It is understood by the parties hereto that it is the intention of the Purchaser to incorporate. Upon condition that such incorporation be completed by closing, all agreements, covenants, and warranties contained herein shall be construed to have been made between Seller and the resultant corporation and all documents shall reflect same.

In fact, Jenofsky and Graziano did file Articles of Incorporation for Kent Enterprises, Inc., with the State Corporation Bureau on October 9, 1971, twelve days prior to the scheduled settlement date. Jenofsky now contends the inclusion of Paragraph 19 in the agreement and the subsequent filing of incorporation papers, released him from any personal liability resulting from the non-performance of the agreement.

The legal relationship of Jenofsky to Kent Enterprises, Inc., at the date of the execution of the agreement of sale was that of promoter. As such, he is subject to the general rule that a promoter, although he may assume to act on behalf of a projected corporation and not for himself, will be held personally liable on contracts made by him for the benefit of a corporation he intends to organize. This personal liability will continue even after the contemplated corporation is formed and has received the benefits of the contract, unless there is a novation or other agreement to release liability.

The imposition of personal liability upon a promoter where that promoter has contracted on behalf of a corporation is based upon the principle that one who assumes to act for a nonexistent principal is himself liable on the contract in the absence of an agreement to the contrary.

[T]here [are] three possible understandings that parties may have when an agreement is executed by a promoter on behalf of a proposed corporation:

When a party is acting for a proposed corporation, he cannot, of course, bind it by anything he does, at the time, but he may (1) take on its behalf an offer from the other which, being accepted after the formation of the company, becomes a contract; (2) make a contract at the time binding himself, with the stipulation or understanding, that if a company is formed it will take his place and that then he shall be relieved of responsibility; or (3) bind himself personally without more and look to the proposed company, when formed, for indemnity.

Both RKO and Jenofsky concede the applicability of alternative No. 2 to the instant case. That is, they both recognize that Jenofsky (and Graziano) was to be initially personally responsible with this personal responsibility subsequently being released. Jenofsky contends the parties, by their inclusion of Paragraph 19 in the agreement, manifested an intention to release him from personal responsibility upon the mere formation of the proposed corporation, provided the incorporation was consummated prior to the scheduled closing date. However, while Paragraph 19 does make provision for recognition of the resultant corporation as to the closing documents, it makes no mention of any release of personal liability. Indeed, the entire agreement is silent as to the effect the formation of the projected corporation would have upon the personal liability of Jenofsky and Graziano. Because the agreement fails to provide expressly for the release of personal liability, it is, therefore, subject to more than one possible construction.

In Consolidated Tile and Slate Co. v. Fox, 410 Pa. 336,339,189 A.2d 228, 229 (1963), we stated that where an agreement is ambiguous and reasonably susceptible of two interpretations, “it must be construed most strongly against those who drew it.”…Instantly, the chancellor determined that the intent of the parties to the agreement was to hold Jenofsky personally responsible until such time as a corporate entity was formed and until such time as that corporate entity adopted the agreement. We believe this construction represents the only rational and prudent interpretation of the parties’ intent.

As found by the court below, this agreement was entered into on the financial strength of Jenofsky and Graziano, alone as individuals. Therefore, it would have been illogical for RKO to have consented to the release of their personal liability upon the mere formation of a resultant corporation prior to closing. For it is a well-settled rule that a contract made by a promoter, even though made for and in the name of a proposed corporation, in the absence of a subsequent adoption (either expressly or impliedly) by the corporation, will not be binding upon the corporation. If, as Jenofsky contends, the intent was to release personal responsibility upon the mere incorporation prior to closing, the effect of the agreement would have been to create the possibility that RKO, in the event of non-performance, would be able to hold no party accountable: there being no guarantee that the resultant corporation would ratify the agreement. Without express language in the agreement indicating that such was the intention of the parties, we may not attribute this intention to them.

Therefore, we hold that the intent of the parties in entering into this agreement was to have Jenofsky and Graziano personally liable until such time as the intended corporation was formed and ratified the agreement. [And there is no evidence that Kent Enterprises ratified the agreement. The decree is affirmed.]

Case Questions

- Does a promoter’s personal liability continue even after the corporation is formed? Can he or she look to the corporation for indemnity after the corporation is formed?

- In what instance(s) is a contract made by a promoter not binding on a corporation?

- In whose favor does a court construe an ambiguous agreement?

De Jure and De Facto Corporations

Cranson v. International Business Machines Corp.

234 Md. 477, 200 A.2d 33 (1964)

HORNEY, JUDGE

On the theory that the Real Estate Service Bureau was neither a de jure nor a de facto corporation and that Albion C. Cranson, Jr., was a partner in the business conducted by the Bureau and as such was personally liable for its debts, the International Business Machines Corporation brought this action against Cranson for the balance due on electric typewriters purchased by the Bureau. At the same time it moved for summary judgment and supported the motion by affidavit. In due course, Cranson filed a general issue plea and an affidavit in opposition to summary judgment in which he asserted in effect that the Bureau was a de facto corporation and that he was not personally liable for its debts.

The agreed statement of facts shows that in April 1961, Cranson was asked to invest in a new business corporation which was about to be created. Towards this purpose he met with other interested individuals and an attorney and agreed to purchase stock and become an officer and director. Thereafter, upon being advised by the attorney that the corporation had been formed under the laws of Maryland, he paid for and received a stock certificate evidencing ownership of shares in the corporation, and was shown the corporate seal and minute book. The business of the new venture was conducted as if it were a corporation, through corporate bank accounts, with auditors maintaining corporate books and records, and under a lease entered into by the corporation for the office from which it operated its business. Cranson was elected president and all transactions conducted by him for the corporation, including the dealings with I.B.M., were made as an officer of the corporation. At no time did he assume any personal obligation or pledge his individual credit to I.B.M. Due to an oversight on the part of the attorney, of which Cranson was not aware, the certificate of incorporation, which had been signed and acknowledged prior to May 1, 1961, was not filed until November 24, 1961. Between May 17 and November 8, the Bureau purchased eight typewriters from I.B.M., on account of which partial payments were made, leaving a balance due of $4,333.40, for which this suit was brought.

Although a question is raised as to the propriety of making use of a motion for summary judgment as the means of determining the issues presented by the pleadings, we think the motion was appropriate. Since there was no genuine dispute as to the material facts, the only question was whether I.B.M. was entitled to judgment as a matter of law. The trial court found that it was, but we disagree.

The fundamental question presented by the appeal is whether an officer of a defectively incorporated association may be subjected to personal liability under the circumstances of this case. We think not.

Traditionally, two doctrines have been used by the courts to clothe an officer of a defectively incorporated association with the corporate attribute of limited liability. The first, often referred to as the doctrine of de facto corporations, has been applied in those cases where there are elements showing: (1) the existence of law authorizing incorporation; (2) an effort in good faith to incorporate under the existing law; and (3) actual use or exercise of corporate powers. The second, the doctrine of estoppel to deny the corporate existence, is generally employed where the person seeking to hold the officer personally liable has contracted or otherwise dealt with the association in such a manner as to recognize and in effect admit its existence as a corporate body.

* * *

There is, as we see it, a wide difference between creating a corporation by means of the de facto doctrine and estopping a party, due to his conduct in a particular case, from setting up the claim of no incorporation. Although some cases tend to assimilate the doctrines of incorporation de facto and by estoppel, each is a distinct theory and they are not dependent on one another in their application. Where there is a concurrence of the three elements necessary for the application of the de facto corporation doctrine, there exists an entity which is a corporation de jure against all persons but the state.

On the other hand, the estoppel theory is applied only to the facts of each particular case and may be invoked even where there is no corporation de facto. Accordingly, even though one or more of the requisites of a de facto corporation are absent, we think that this factor does not preclude the application of the estoppel doctrine in a proper case, such as the one at bar.