This is “Double-Entry Bookkeeping”, section 4.3 from the book Business Accounting (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

4.3 Double-Entry Bookkeeping

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Explain the history of double-entry bookkeeping.

- List the four steps followed in the accounting process.

- Indicate the purpose of a T-account.

- List the basic rules for making use of debits and credits.

- Describe the reason that debits and credits are always equal for every transaction.

Double-Entry Bookkeeping

Question: Transaction analysis determines the changes that occur in accounts whenever various events take place. Financial statements eventually provide a formal structure to communicate the resulting balances to an array of interested parties.

- Revenues, expenses, gains, and losses are presented on an income statement where they are combined to arrive at reported net income for the period.

- Total income earned and dividends distributed by the company over its entire life are netted to compute the retained earnings balance to be reported.

- Assets, liabilities, capital stock, and retained earnings are all displayed on a balance sheet.

- Changes in cash are separated into operating activities, investing activities, and financing activities and disclosed on a statement of cash flows.

- Notes offer pages of additional explanatory information.

The amount of financial data that is readily available to any decision maker is impressive.

Accountants for a business of any significant size face a daunting challenge in creating financial statements. They must gather, measure, and report the impact of the many varied events that occur virtually every day. As an example, for 2010, Xerox Corporation disclosed revenues of over $21.6 billion and operating expenses and other costs of $20.8 billion. At the end of 2010, the Kellogg Company reported holding $1.1 billion in inventory—which is a lot of cereal—and indicated that its operating activities that year generated a net cash inflow of approximately $1 billion. How can any organization possibly amass and maintain such an enormous volume of data so that financial statements can be produced with no material misstatements?

Answer: Over five hundred years ago, Venetian merchants in Italy developed a system that continues to serve in the twenty-first century as the basis for accumulating financial data throughout much of the world. Today, when every aspect of modern society seems to be in a constant state of flux, a process that has remained in use for over five centuries is almost impossible to comprehend. However, the double-entry bookkeepingA mechanical process created over five hundred years ago and documented by Fra Luca Bartolomeo de Pacioli that facilitates the gathering and reporting of financial information. procedures that were first documented in 1494 by Fra Luca Bartolomeo de Pacioli (a friend of Leonardo da Vinci) remain virtually unchanged by time. Organizations, both small and large, use the fundamentals of double-entry bookkeeping to gather the monetary information needed to produce financial statements that are fairly presented according to the rules of U.S. GAAP or IFRS.

Analyze, Record, Adjust, and Report

Question: This assertion sounds like science fiction. It hardly seems believable that Xerox keeps up with over $21.6 billion in revenue (approximately $59 million per day) using the same methods that Venetian merchants applied to their transactions during the Renaissance. How can a five-hundred-year-old bookkeeping system possibly be usable in today’s modern world?

Answer: State-of-the-art computers and other electronic devices are designed to refine and accelerate the financial accounting process, but the same basic organizing procedures have been utilized now for hundreds of years. In simplest terms, accounting systems are all created to follow four sequential steps:

- Analyze

- Record

- Adjust

- Report

The first two of these steps are studied in this chapter. As explained previously, financial accounting starts by analyzing each transaction—every event that has a monetary impact on the organization—to ascertain the changes created in accounts such as rent expense, cash, inventory, and dividends paid. Fortunately, a vast majority of any company’s transactions are repetitive so that many of the effects can be easily anticipated. A sale on credit always increases both accounts receivable and revenue. Regardless of the time or place, a cash purchase of a piece of equipment increases the balance reported for equipment while decreasing cash. Computer systems can be programmed to record the impact of these events automatically allowing the accountant to focus on analyzing more complex transactions.

Debits, Credits, and T-Accounts

Question: The second step in the financial accounting process is “record.” At the beginning of this chapter, a number of transactions were presented and their impact on individual accounts determined. Following this analysis, some method must be devised to capture the information in an orderly fashion. Officials could just list the effect of each transaction on a sheet of paper:

“Increase inventory $2,000 and increase accounts payable $2,000.”

“Increase salary expense $300 and decrease cash $300.”

“Increase cash $9,000 and increase note payable $9,000.”

However, this process is slow and poorly organized. A more efficient process is required for companies like Xerox and Kellogg. After all monetary changes are identified, how are these effects accumulated?

Answer: An essential step in understanding double-entry bookkeeping is to realize that financial information is accumulated by accountsDetailed records of the transactions and current balances of individual assets, liabilities, stockholders’ equity, revenues and expenses.. As mentioned previously, every balance to be reported in a set of financial statements is maintained in a separate account. Thus, for assets, an individual account is established to monitor cash, accounts receivable, inventory, and so on. To keep track of expenses, a number of additional accounts are needed, such as cost of goods sold, rent expense, salary expense, and repair expense. The same is true for revenues, liabilities, and other categories. A small organization might utilize only a few dozen accounts in its entire record-keeping system. A large business probably has thousands.

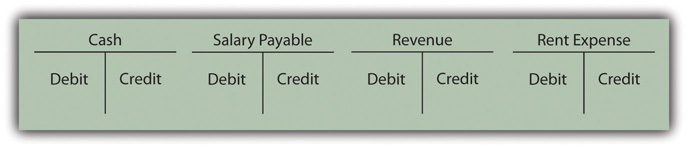

Based on the original Venetian model, the balance for each account is monitored in a form known as a T-accountMaintains the monetary balance for each of the accounts reported by an organization with a left (debit) side and a right (credit) side used to show increases and decreases. as displayed in Figure 4.2 "Examples of Common T-Accounts". This structure provides room for recording on both the left side (known as the debitLeft side of a T-account; it indicates increases in assets, expenses, and dividends paid as well as decreases in liabilities, capital stock, and revenue and gains. side) and the right side (the creditRight side of a T-account; it indicates increases in liabilities, capital stock, retained earnings, and revenue and gains as well as decreases in assets, expenses, and dividends paid. side).

Figure 4.2 Examples of Common T-Accounts

One side of every T-account records increases; the other side records decreases. For over five hundred years, the following rules have applied.

In some accounts, debits indicate an increase and credits indicate a decrease. They are grouped together because they all refer to costs.

Increase Shown with a Debit:

- Expenses and losses

- Assets

- Dividends paidOne method to keep track of these accounts initially is to remember them as the “DEAD” accounts: debits increase, expenses and losses, assets, and dividends paid. Quickly, though, through practice, such mnemonic devices will not be needed.

In other accounts, credits indicate an increase and debits indicate a decrease. They are grouped together because they all reflect sources of funding.

Increase Shown with a Credit:

- Liabilities

- Capital stock

- Revenues and gains

- Retained earningsChanges in the balance reported for retained earnings normally do not come as a direct result of a transaction. As discussed previously, this account reflects all the net income earned to date reduced by all dividend payments. Income is made up of revenues, expenses, gains, and losses. Accounting recognition of revenues and gains (which increase with credits) lead to a larger retained earnings balance. Expenses, losses, and dividends paid (which all increase with debits) reduce retained earnings. Consequently, credits cause an increase in retained earnings whereas debits produce a decrease.

The debit and credit rules for these seven general types of accounts provide a short-hand method for recording the financial impact that a transaction has on any account. They were constructed in this manner so that the following would be true:

Basic Rule for Double-Entry Bookkeeping Debits must always equal credits for every transaction.At first view, the debit and credit rules might seem completely arbitrary. However, they are structured to mirror the cause-and-effect relationship found in every transaction. This is the basis of what the Venetian merchants came to understand so long ago: every effect must have a cause.

- Assume an asset (such as cash) increases. As shown here, that change is recorded on the debit side of the T-account for that asset. What could cause an asset to become larger? A reason must exist. A liability—possibly a bank loan—could have been incurred (recorded as a credit); capital stock could have been issued to an owner (a credit); revenue could have been earned from a sale (a credit). The list of possible reasons is relatively short. In each case, the debit (increase) to the asset is caused by an equal and offsetting credit.

- Assume an asset (such as cash) decreases. This change is recorded on the credit side of the asset’s T-account. What might cause this reduction? An expense could have been paid (recorded as a debit); a dividend could have been distributed to shareholders (a debit); a liability could have been extinguished (a debit); another asset could have been acquired (a debit). Once again, the cause-and-effect relationship is reflected; the debits equal the credits. Each effect is set equal and opposite to its cause.

There are only seven types of accounts. Therefore, a mastery of debit and credit rules can be achieved with a moderate amount of practice. Because of the fundamental role that debits and credits play within every accounting system, this knowledge is well worth the effort required to obtain it.

Test Yourself

Question:

A company incurs a transaction that is reflected in its accounting system through a debit to salary expense and a credit to salary payable for salary for one month. Which one of the following is the best description of the transaction that took place?

- Employee salaries for the past month were paid.

- Employee salaries for the upcoming month were paid.

- Employee salaries for the past month are recognized but not paid.

- Employee salaries for the past month have been accrued and are now paid.

Answer:

The correct answer is choice c: Employee salaries for the past month are recognized but not paid.

Explanation:

A debit to an expense is an increase, while a credit to a liability is also an increase. The expense increased, indicating that salary for the past month has been incurred. The payable also increased, which means that the amount owed to the employees has risen. Recognition is made here that an expense has been incurred but not yet paid.

Key Takeaway

Most companies participate in numerous transactions each day that must be examined and organized so that financial statements can eventually be prepared. This process requires four steps: analyze, record, adjust, and report. Over five hundred years ago, double-entry bookkeeping was created as a mechanical process to facilitate this gathering and reporting of financial information. A T-account is maintained for each account (such as cash, accounts payable, and rent expense) to be reported by a company. The left side of the T-account is the debit side, and the right side is the credit. Expenses and losses, assets, and dividends paid increase with debits. Liabilities, revenues and gains, capital stock, and retained earnings increase with credits. Debits always equal credits because every transaction must have both an effect and a cause for that effect.