This is “Brains, Bodies, and Behavior”, chapter 3 from the book Beginning Psychology (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 3 Brains, Bodies, and Behavior

Did a Neurological Disorder Cause a Musician to Compose Boléro and an Artist to Paint It 66 Years Later?

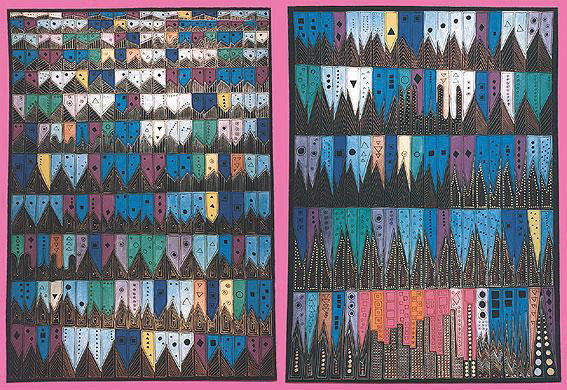

In 1986 Anne Adams was working as a cell biologist at the University of Toronto in Ontario, Canada. She took a leave of absence from her work to care for a sick child, and while she was away, she completely changed her interests, dropping biology entirely and turning her attention to art. In 1994 she completed her painting Unravelling Boléro, a translation of Maurice Ravel’s famous orchestral piece onto canvas. As you can see in Figure 3.1, this artwork is a filled with themes of repetition. Each bar of music is represented by a lacy vertical figure, with the height representing volume, the shape representing note quality, and the color representing the music’s pitch. Like Ravel’s music (see the video below), which is a hypnotic melody consisting of two melodial themes repeated eight times over 340 musical bars, the theme in the painting repeats and builds, leading to a dramatic change in color from blue to orange and pink, a representation of Boléro’s sudden and dramatic climax.

Figure 3.1 Unravelling Boléro

Adams’s depiction of Ravel’s orchestral piece Boléro was painted during the very early phase of her illness in 1994.

Source: Photo courtesy of New Scientist, http://www.newscientist.com/data/images/ns/cms/dn13599/dn13599-1_567.jpg.

Maurice Ravel’s Composition Boléro (1928)

This is a video clip of Maurice Ravel’s Boléro, composed in 1928 during the early phases of his illness.

Shortly after finishing the painting, Adams began to experience behavioral problems, including increased difficulty speaking. Neuroimages of Adams’s brain taken during this time show that regions in the front part of her brain, which are normally associated with language processing, had begun to deteriorate, while at the same time, regions of the brain responsible for the integration of information from the five senses were unusually well developed (Seeley et al., 2008).Seeley, W. W., Matthews, B. R., Crawford, R. K., Gorno-Tempini, M. L., Foti, D., Mackenzie, I. R., & Miller, B. L. (2008). “Unravelling Boléro”: Progressive aphasia, transmodal creativity, and the right posterior neocortex. Brain, 131(1), 39–49. The deterioration of the frontal cortex is a symptom of frontotemporal dementia, a disease that is associated with changes in artistic and musical tastes and skills (Miller, Boone, Cummings, Read, & Mishkin, 2000),Miller, B. L., Boone, K., Cummings, J. L., Read, S. L., & Mishkin, F. (2000). Functional correlates of musical and visual ability in frontotemporal dementia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 458–463. as well as with an increase in repetitive behaviors (Aldhous, 2008).Aldhous, P. (2008, April 7). “Boléro”: Beautiful symptom of a terrible disease. New Scientist. Retrieved from http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn13599-bolero-beautiful-symptom-of-a-terrible-disease.html

What Adams did not know at the time was that her brain may have been undergoing the same changes that Ravel’s had undergone 66 years earlier. In fact, it appears that Ravel may have suffered from the same neurological disorder. Ravel composed Boléro at age 53, when he himself was beginning to show behavioral symptoms that were interfering with his ability to move and speak. Scientists have concluded, based on an analysis of his written notes and letters, that Ravel was also experiencing the effects of frontotemporal dementia (Amaducci, Grassi, & Boller, 2002).Amaducci, L., Grassi, E., & Boller, F. (2002). Maurice Ravel and right-hemisphere musical creativity: Influence of disease on his last musical works? European Journal of Neurology, 9(1), 75–82. If Adams and Ravel were both affected by the same disease, this could explain why they both became fascinated with the repetitive aspects of their arts, and it would present a remarkable example of the influence of our brains on behavior.

Every behavior begins with biology. Our behaviors, as well as our thoughts and feelings, are produced by the actions of our brains, nerves, muscles, and glands. In this chapter we will begin our journey into the world of psychology by considering the biological makeup of the human being, including the most remarkable of human organs—the brain. We’ll consider the structure of the brain and also the methods that psychologists use to study the brain and to understand how it works.

We will see that the body is controlled by an information highway known as the nervous systemA collection of hundreds of billions of specialized cells that transmit information between different parts of the body., a collection of hundreds of billions of specialized and interconnected cells through which messages are sent between the brain and the rest of the body. The nervous system consists of the central nervous system (CNS)The brain and the spinal cord., made up of the brain and the spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system (PNS)The nerves that link the CNS to the skin, muscles, and glands., the neurons that link the CNS to our skin, muscles, and glands. And we will see that our behavior is also influenced in large part by the endocrine systemThe chemical regulator of the body, composed of the glands that secrete hormones., the chemical regulator of the body that consists of glands that secrete hormones.

Although this chapter begins at a very low level of explanation, and although the topic of study may seem at first to be far from the everyday behaviors that we all engage in, a full understanding of the biology underlying psychological processes is an important cornerstone of your new understanding of psychology. We will consider throughout the chapter how our biology influences important human behaviors, including our mental and physical health, our reactions to drugs, as well as our aggressive responses and our perceptions of other people. This chapter is particularly important for contemporary psychology because the ability to measure biological aspects of behavior, including the structure and function of the human brain, is progressing rapidly, and understanding the biological foundations of behavior is an increasingly important line of psychological study.