This is “Practices for Making Your Organizational Culture More Accountable”, section 9.4 from the book Beginning Organizational Change (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

9.4 Practices for Making Your Organizational Culture More Accountable

Organizational cultures are very difficult to change and it takes considerable time to do so. The organizational founder and previous experiences of an organization help to establish “how things get done around here”; and these norms, values, and assumptions are often not conscious or easily changed.

However, cultures are particularly sensitive to the behaviors and attitudes of senior leaders. Therefore, senior leaders do have a special interest and responsibility in reinforcing positive and productive aspects of a culture, and replacing negative and unproductive aspects. Furthermore, due to the intangible and relatively intransigent nature of culture, productive cultures can be a source of sustained competitive advantage. The following are seven different things that can be done to make your culture more accountable. Since a culture consists of the artifacts, values, and assumptions that drive organizational action, changing a culture needs to involve change in all three areas. Listed below are seven principles that can assist you in making your culture more accountable for results.

Practice 1: Begin With a Focus on Results Being Sought

Effective accountability means that there is a clear understanding of the results being sought throughout the entire organization. This requires intense thought and ongoing dialogue about what the organization’s purpose is, and what it is trying to achieve. It starts with a clear understanding of the overall mission of the organization and then cascades down into performance standards expected for each and every individual within that organization. Without asking the question as to “what is wanted” before deciding how to do it, organizational members who act without full knowledge of the results required may work harder but accomplish less.Ulrich, Zenger, & Smallwood (1999), p. 21.

Accompanying this clarity on results is the clarity of the goals being sought. Sometimes, organizational goals are ambiguous and unenforceable, what some call “resolutions.” While resolutions may sound good, the actions required are often not clear and the results being sought can be up to interpretation. Clear goals, on the other hand, specify what is desired and by when. And when individuals commit to clear goals, positive outcomes emerge.Heath and Heath (2008).

Practice 2: Assign Responsibility for Results to Everyone in the Organization

If your organization has difficulty assigning responsibility for results, consider responsibility charting. This technique is essentially a matrix with results desired in one column, and individuals in an organizational unit in the other columns. Matrix entries specify who is responsible for what and, if possible, when results are expected. With this relatively simple approach, responsibility and clarity is much more clear, especially if there is a review of the results achieved when compared with the results desired.

But not all responsibility can be assigned in advance. Sometimes individuals volunteer to be accountable for certain results in special circumstances. Stories are an effective tool for eliciting volunteers to become more accountable, particularly when the story involves a previous member of the organization who overcame overwhelming odds to deliver extraordinary results. Success stories are part of every culture, and success stories about accountability help to make the culture more accountable as well as encourage volunteerism.Wines and Hamilton (2009).

In your attempt to be clear about responsibility, effective communication is essential. Sometimes leaders know exactly what they want, but they don’t communicate clearly what is desired. Sometimes leaders have a vague idea of what is wanted and dialogue needs to be conducted with subordinates to help clarify matters. When the dialogue is open, candid, and informal, clarity ensues and accountability results.Bossidy and Charan (2002), p. 102.

Practice 3: Leaders Should Demonstrate the Behaviors That Align With the Proposed Change

Culture change starts and gains momentum with changed behavior on the part of the leaders of that organization or organizational unit. Nothing kills a change initiative faster than leaders who espouse certain behaviors and attitudes, but demonstrate different ones. For example, if a leader announces the importance of controlling costs more carefully, but then he or she arranges for a lavish executive retreat or decorates his or her office in excessive ways, the rest of the organization takes notice. Hence, leaders need to exercise care in the behaviors they exhibit.Bossidy and Charan (2002), p. 105.

In addition, leaders need to be careful as to behaviors that they tolerate. If results are being stressed and their subordinate does not deliver results, then there needs to be demonstrable consequences. This applies to both meeting the numbers and behaving consistently with the organization’s values. Indeed, it has been observed that if a nonperformer gets high enough in the organizational hierarchy and is not held accountable, that person can literally destroy the organization.Bossidy and Charan (2002), p. 115.

Practice 4: Measure the Right Performance Standards and Do It Rigorously

It is a skill to link desired results and goals with standards and metrics of performance. If a performance standard is done well, achievement of that standard will realize the results being sought. Designing realistic timetables and appropriate performance standards is not easy to do well, and it is particularly difficult for large, complicated projects. And for those change initiatives that have an extended time horizon, intermediate milestones must be set with care. Nonetheless, rigorous standard setting is an essential activity if an accountable culture is being sought.Osborne (1993).

Clearly, performance measures need to be balanced or else the organization risks becoming unbalanced. Consequently, this suggests that multiple performance standards are required. However, if the performance standards are too numerous, then assessing performance is no longer possible. Overall, focusing on a relatively few, balanced performance standards works best for making the organization more accountable.Ulrich, Zenger, & Smallwood (1999).

When designing performance standards, it is sometimes helpful to distinguish between ends and means standards. When the strategic goals are established and measureable, then metrics that focus on the end result are most appropriate. However, when the strategic goals are changing and not easily measured, then metrics that focus on the means for bringing about the change are most appropriate. In either case, however, measurements can and should be applied.Melnyk, Hanson, & Calantone (2010).

Finally, most people assume that utilizing performance standards implies a bureaucratic organization; however, this does not have to be the case. Accountability can be achieved in nonhierarchical organizational structures when it comes from within the employee or is reviewed in nonbureaucratic ways.Ulrich, Zenger, & Smallwood (1999), p. 97.

Practice 5: Make Sure That Cultural Artifacts Support Accountability

As discussed previously, cultural artifacts are the visible expressions of the underlying values and assumptions that pervade an organization. When changing a culture, changing the visible artifacts makes a conscious and unconscious impression on the organization’s members. There are at least five types of cultural artifacts: (a) normal behavior, (b) myths and sagas, (c) language systems and metaphors, (d) symbols, rituals, and ceremonies, and (e) physical surroundings including interior design and physical equipment.Shrivastava (1985).

One cultural artifact surrounding accountability is who gets celebrated and who gets ignored. Clearly, celebrating and promoting individuals who deliver results on time and within budget is one way to support movement to more accountable culture. Also, individuals who don’t deliver results on time or within budget need to be privately confronted, coached, and sometimes removed from the organization.Bossidy and Charan (2002).

The transformation of Continental Airlines is a prime example of how important changing artifacts are to making a culture more accountable. To change behavioral norms that had been associated with low productivity, the leaders instituted a bonus system that rewarded high levels of productivity. In order to align the culture with the new business strategy, the leader’s next act was to reduce the corporate policy manual from 800 pages to just 80 pages and then conduct a ritual where the former manuals were burned by the employees. In addition, the catch phrase “from worst to first” was used to focus employees’ attention on the desired results. Whenever key milestones were achieved, corporate celebrations were arranged. And executives were required to work on holidays so that “we are all in this together” in Continental’s effort to become more accountable and productive. And the repainting of the jets, renovating of the gateways, and purchasing of state-of-the-art information technology all contributed to the turnaround initiative.Higgins and McAllaster (2004).

Practice 6: Discuss Assumptions Underlying Actions Dealing With Accountability

The fastest but perhaps most challenging way to change an organizational culture is to change the assumptions underlying that culture. Since culture is the “taken-for-granted” way of doing things within an organization, this is not an easy task. However, change-capable organizations are adept at naming the assumptions underlying organizational actions and changing those assumptions when they no longer serve the organization.

Surfacing and debating assumptions is the means by which cultural change is achieved, and paying attention to assumptions around accountability is a key way to make your organization more change capable. Larry Bossidy and Ram Charan note,

Debate on assumptions is one of the most critical parts of any operating review—not just the big-picture assumptions but assumptions specifically linked with their effects on the business, segment by segment, item by item. That’s a key part of what’s missing in the standard budget review. You cannot set realistic goals until you’ve debated the assumptions behind them.Bossidy and Charan (2002), p. 236.

Practice 7: Make Sure That the Reward System Focuses on Accountability

A key aspect of accountability means that there are consequences to meeting or not meeting performance standards. This suggests that the reward and recognition system needs to celebrate and reward those who consistently deliver results and develop a reputation for accountability, and it needs to confront and punish those who consistently fail to deliver results.Kerr and Slocum (2005).

Many organizations do a good job celebrating and recognizing good performance. Very few organizations deal with nonperformers well even though this is a key process for any organization that takes accountability seriously. Most employees like knowing where they stand in terms of performance, and the performance evaluation system is central to making an organization accountable. It is particularly important that the performance evaluation system is based on hitting predefined targets and standards as much as possible. However, care must be exercised in selecting the right standards, not just those that are easiest to measure.Kerr (1975).

In the absence of rigorously defined standards, performance evaluation becomes more focused on nonperformance criteria. Since each organization is unique, customized reward and recognition systems are becoming the norm for organizations seeking greater accountability.Heneman, Fisher, & Dixon (2001).

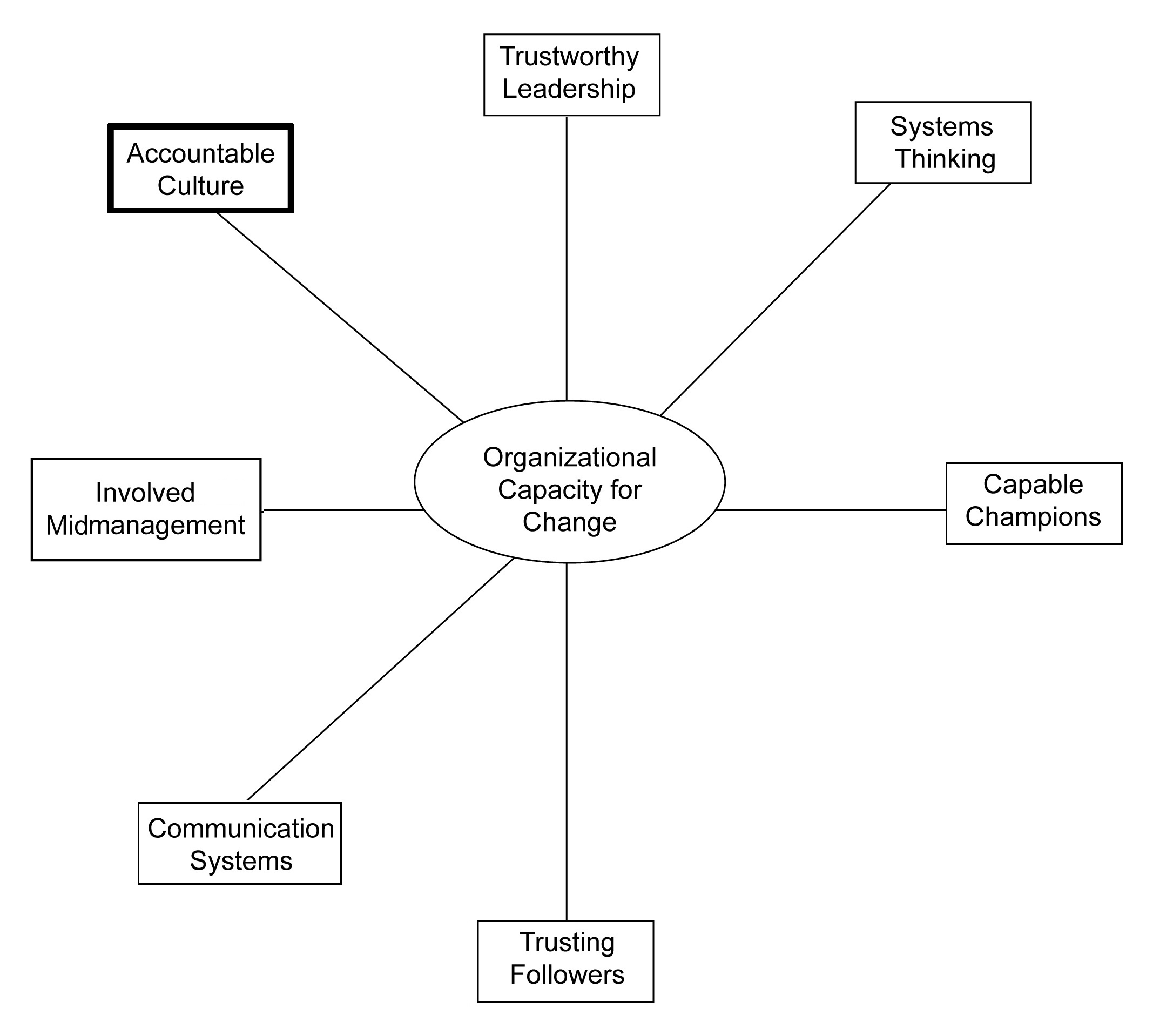

In sum, creating and maintaining a culture of accountability is essential to bring about a change-capable organization. This does not mean that organizations need to measure everything and become more mechanical. If thoughtfully developed, however, measurements and responsibility assignments can aid in organizational learning and adaptability. This dimension, and the previous dimensions discussed, is graphically depicted in Figure 9.1 "The Seventh Dimension of Organizational Capacity for Change: Accountable Culture".

Figure 9.1 The Seventh Dimension of Organizational Capacity for Change: Accountable Culture