This is “Recruiting, Socializing, and Disengaging”, chapter 10 from the book An Introduction to Organizational Communication (v. 0.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 10 Recruiting, Socializing, and Disengaging

Working Life

© Thinkstock

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, an average person (as of 2010) can expect to live until he or she is about 78.5 years of age.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Life expectancy. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lifexpec.htm Let’s say you start working a 40 hour a week job right out of college at age 22 and have the luxury of working until you’re 65, then you will have worked approximately 43 years. There are 52 weeks in a year, so let’s say you’re really lucky and only have to work 48 of them. If you work only an 8 hour shift (with 30 minutes for lunch), you’ll work approximately 1,800 hours per year or 77,400 over the course of your working career. At this rate, your work career will account for 11.33 percent of your life. And trust us, if you look at the numbers we’ve provided here, we are clearly low-balling our estimates. In reality, depending on the type of career choice you make, you could easily end up spending 15–20 percent of your life working.

Most individuals will not have a singular job. In fact, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, “the baby boom (1957–1964) held 11.3 jobs from age 18 to age 46.”Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2012, July 25). Number of jobs held, labor market activity, and earnings growth among the youngest baby boomers: Results from a longitudinal survey summary. Retrieved from: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/nlsoy.nr0.htm For this reason, we spend a good chunk of our time being recruited by organizations, entering into new organizations, acclimating ourselves to new organizations, and eventually leaving organizations. This chapter is going to focus on the process of recruiting, socializing, and leaving organizations.

10.1 Recruiting

Learning Objectives

- Enumerate the cost of recruitment and why effective recruitment affects an organization’s bottom line.

- Explain Breaugh, Macan, and Grambow five stage model of employee recruitment.

- Recognize the problems associated with traditional organizational recruitment strategies.

- Explain realistic job preview theory and its importance in the recruitment process.

- Differentiate among the different mediums for presenting realistic job previews.

- Examine the outcomes realistic job previews have for organizations.

© Thinkstock

Organizations spend a good deal of time and money recruiting people to work in organizations. This section is going to examine the process of recruiting new organizational members. Believe it or not, recruitment is very important for an organization because poor recruitment can be a very costly mistake. Table 10.1 "The Cost of Recruitment" shows research from a handful of studies that examine the cost for recruiting a new employee. Leigh Branham estimates that the costs associated with recruiting someone can be anything from 25 to 200 percent of the person’s annual salary.Branham, L. (2000). Keeping the people who keep you in business: 24 ways to hang on to your most valuable talent. New York, NY: AMACOM. Overall, recruiting new employees is a time consuming and expensive process. In this section, we’re going to examine the recruitment process along with various issues related to employee expectations and finding the best talent.

Table 10.1 The Cost of Recruitment

| Study Description | Findings |

|---|---|

| Examined the cost of recruiting both operations and management in five-star hotels in Australia.Davidson, M. C. G., Timo, N., & Wang, Y. (2010). How much does labour turnover cost? A case study of Australian four- and five-star hotels. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22, 451–466. doi: 10.1108/09596111011042686 | $9,591 for an 8 hour employee. $109,909 for a manager. |

| Examined how much it cost to recruit a new front-line desk clerk at hotels in New York City and Miami.Hinkin, T. R., & Tracey, J. B. (2000). The cost of turnover : Putting a price on the learning curve. Cornell Hotel & Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 41, 14–21. doi: 10.1177/001088040004100313 | $5,827—Miami |

| $12,246—NYC | |

| Examined the costs associated with recruiting a number of different occupations.Sommer, R. D. (2000). Retaining intellectual capital in the 21st century. | $109,909—Journeyman Machinist |

| $133,000 for an HR manager | |

| $150,000 for an accounting professional | |

| Examined the cost of recruiting public school teachers in Texas.Texas Center for Educational Research. (2000, October). The cost of teacher turnover: Report Prepared for the Texas State Board for Educator Certification. Austin, TX: Texas Center for Educational Research. | $3,000 and $4,000 per teacher |

| Examined the costs of various jobs in the state of Louisiana.Louisiana Department of State Civil Service. (2011, January 13). Report on turnover rates for non-classified employees. Retrieved from: http://senate.legis.state.la.us/streamline/Topics/2011/Act%20879%20Turnover%20Report%20AMENDED%20Jan%2013%202011.pdf | Average of $25,000 for jobs that are high stress protective services (e.g., police officers & correction staff). |

The Recruitment Process

Recruitment takes a lot of economic and human resources to do effectively. Unfortunately, some organizations do not adequately think through the basic strategies for recruiting to ensure the maximum benefits of the recruitment process. Maybe an organization is more concerned with filling a position than finding the best person for the job. Other organizations end up with people who have exaggerated their qualifications in order to get the job. Some organizations try to paint an unrealistic rosy-picture of what it’s like to work there only to end up with new hires who become disgruntled once they are faced with the actual reality of the job. Whatever the reasons that exist for poor recruitment, problematic recruitment is a reality in many organizations. According James Breaugh, employee recruitment encompasses four specific actions on the part of an organization:

- bring a job opening to the attention of potential job candidates who do not currently work for the organization,

- influence whether these individuals apply for the opening,

- affect whether they maintain interest in the position until a job offer is extended, and

- influence whether a job offer is accepted.Breaugh, J. A. (2008). Employee recruitment, Current knowledge and important areas for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 18, 103–118. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr:2008.07.003, pgs. 103–104.

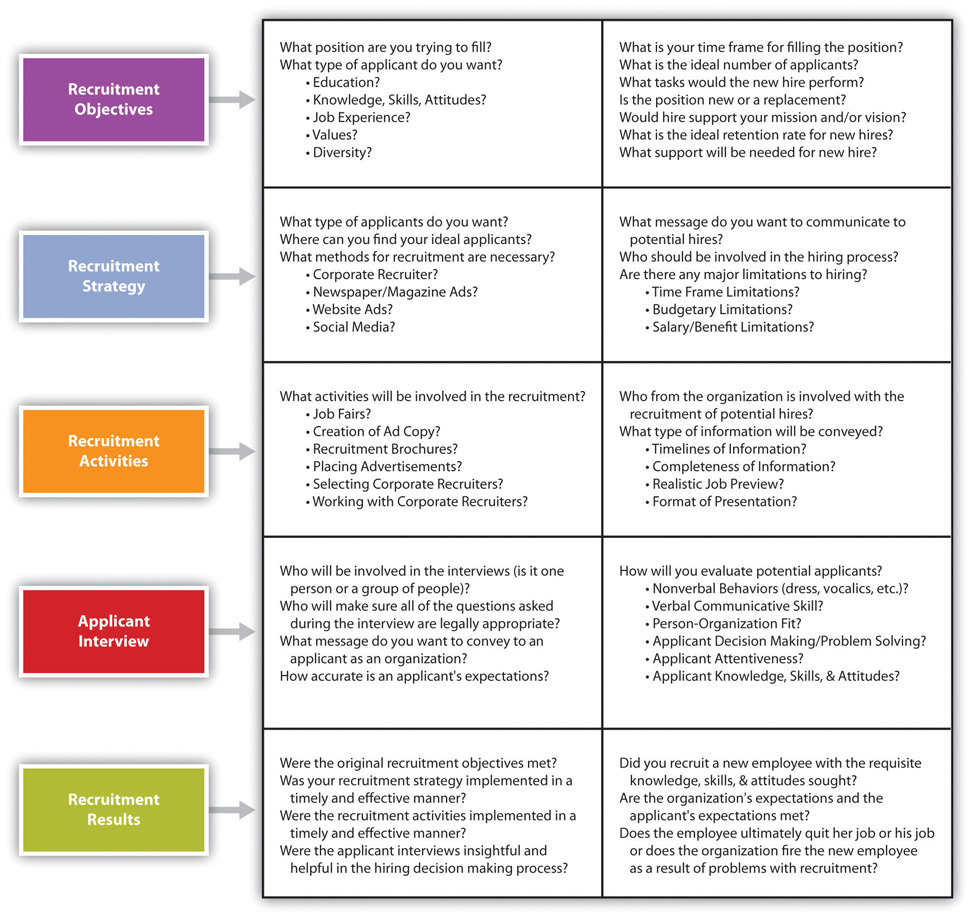

To help organizations think through effective employee recruitment, James Breaugh, Therese Macan, and Dana Grambow proposed a simple five-step model for understanding recruitment in modern organizations, which can be seen in Figure 10.1 "Model of Employee Recruitment".Breaugh, J. A., Macan, T. H., & Grambow, D. M. (2008). Employee recruitment: Current knowledge and directions for future research. In G. P. Hodgkinson & J. K. Ford

Figure 10.1 Model of Employee Recruitment

Recruitment Objectives

The first stage of recruiting new employees consists of determining the basic objectives for the new employee. Are you creating a brand new position or attempting to refill a position because of voluntary or involuntary turnover? At this stage in the recruitment process, you need to truly brainstorm everything from the type of applicant you’re looking for (e.g., educational background, job experience, skill set, etc.) to the role this person will actually play within the organization itself. The more specific you can be at this point in the recruitment process, the easier it will be to weed out eventual applicants who simply do not meet the basic objectives of the organization.

Recruitment Strategy

The next stage in recruitment involves thinking through the specific strategies that the organization plans to employ to recruit potential applicants. If you look in Figure 10.1 "Model of Employee Recruitment", you’ll notice that the questions asked during this phase primarily deal with determining how you will find your applicant pool and then how you will craft specific messages targeted at potential applicants that will entice them to apply. First, you need to know what type of applicant you need to target. For example, are you looking for someone who has just a high school education or are you looking for someone who has an MBA and 20 plus years of experience running nonprofit organizations? You’ll notice that this part of the recruitment strategy stems directly out of recruitment objectives.

Second, you need to think about the organization’s messaging strategy. The messaging strategy includes everything from crafting specific messages to determining the best possible outlets for these messages. For entry-level, minimum wage applicants, you may create simple, straightforward descriptions of the job and post them on local job websites or in the newspaper. When attempting to hire a senior-level executive, you may work with a consultant known as an external corporate recruiter during this process. An external corporate recruiterAn individual (or group of individuals) who have specific expertise in searching for and recruiting potential job applicants. is an individual (or group of individuals) who have specific expertise in searching for and recruiting potential job applicants. Because corporate recruiters have specific expertise in the recruitment process, they can help an organization in a number of specific ways. First, they can help an organization decrease the amount of time that it takes to search for and eventually hire a new employee (commonly referred to as the time to hireThe amount of time that it takes to search for and eventually hire a new employee.). External corporate recruiters often specialize in specific industries or types of positions, so they already have a network of potential applicants or know how to target potential applicants. Second, they can increase the quality and quantity of the candidate pool. Next, they can help an organization keep its recruiting costs down because of the focused nature of the job search itself. Lastly, they can ensure that all governmental regulations associated with recruitment and hiring are met. Although most human resource personnel can also accomplish this function, sometimes a second pair of eyes not related to the organization can be important to ensure compliance with relevant laws and regulations.

Recruitment Activities

Once you’ve determined your objectives and your strategy, it’s time to actually let the rubber hit the road and start the recruitment of potential applicants. At this point, you’re basically involved in three specific activities. First, you’re engaged in the day-to-day process of searching for and recruiting candidates. This stage can involve everything from placing advertisements on a job website to attending career fairs at a local college or university.

Next, you need to think through all of the internal resources that will be involved in the recruitment process. Who will create job ads? How much time do you have devoted to recruitment? Who is going to oversee the entire recruitment project? Recruitment should have a central project manager who oversees the entire process. If you have too many different people attempting to run your recruitment, you will run into serious problems. As such, it’s important to have a specific individual who is ultimately in charge of the actual recruitment process to ensure all of the small steps are completed accurately and in a timely fashion.

Lastly, you’re crafting the specific messages you want potential applicants to see and/or hear. Whether you’re creating a simple call for applicants in a local newspaper or creating an online video to entice applicants, a lot of time is involved in the crafting of effective messages targeted towards applicants. These messages should be both informative (explaining the job and the types of applicants sought) and persuasive (enticing people to apply). In addition to creating the messages, you need to determine where these messages will ultimately been seen or heard by the types of applicants you desire. Although your strategy for this process was determined in the previous step, at this step in the process you need to implement and adjust your targeted message outlets as necessary.

Applicant Interview

Once you have started to receive applications for your position, it’s time to start going through the stack of potential employees. Before you actually get to the interview step, you need to systematically go through the applications and determine which ones are viable candidates and which ones simply are not. There are many people who simply apply to any and every job whether they have the background or skills necessary to complete the job. The first step in screening out individuals is to have a standard set of objectives for determining the qualifications of the applicant. By employing this objective standard, you can generally weed through a giant portion of the applicants and easily determine the ones that you may want to interview.

For low-level or entry level positions, the recruitment process is generally more straight forward and involves less expense on the part of the organization. These interviews may simply take place within the organization on the day someone fills out an application if a manager is readily available.

On the other hand, when an organization is recruiting a professional position or senior-level executive, there may be a whole interview process in place. There are a number of different types of interviews an organization can take. Some organizations employ telephone interviews first to determine which applicants should be brought to the organization for a face-to-face interview. Today it’s also common to do this first round of interviews using video conferencing software like Skype. The goal of this first set of interviews is to help the recruiters focus their recruitment efforts to a handful of potential applicants they may wish to interview on the organization’s campus. After the telephone interviews, the recruitment team may finalize their list of applicants and either bring them directly to the organization for an interview or employ an off-campus face-to-face interview.

An off-campus face-to-face interviewWhen an organization arranges to have an off-site location (typically in or near an airport) to conduct a round of interviews. (sometimes called a flyover interview) occurs when an organization arranges to have an off-site location (typically in or near an airport) to conduct a round of interviews. In essence, interviewees are flown to the airport and then taken to a conference room within the airport or nearby the airport for a face-to-face interview with the recruitment team. Once the interview is over, the applicant is put back on her or his plane and sent home. Many organizations use this strategy when recruiting senior-level executives because there is nothing quite like a face-to-face interview and these can be cheaper than an on-campus face-to-face interview.

An on-campus face-to-face interviewWhen an organization brings the individual to the organization for an interview. occurs when an organization brings the individual to the organization for an interview. On-campus face-to-face interviews can last from a half-day interview to a multi-day interview depending on type of hire an organization is attempting. The more senior the position, the more likely the organization will involve an extended interview process in an attempt to gain a more thorough understanding of the possible fit of the applicant. These interviews can be very expensive because they involve the costs of transportation, housing, food, and entertainment during the interview.

Obviously, these are not the only types of interviews that organizations can employ, but they are different enough to demonstrate the array of possible choices an organization has for conducting an interview. As you can see from the above descriptions, the interview process can be as cheap as the time lost while a manger conducts an on-the-spot interview to one that could cost over one-hundred thousand dollars. For this reason, interviews should be conducted strategically looking for the various factors discussed in Figure 10.1 "Model of Employee Recruitment".

Recruitment Results

The final stage of recruitment examines the results of the recruitment process itself. Once an applicant has signed a contract and joined your organization, it’s always a smart idea to objectively analyze how recruitment went in an effort to improve the process for future hires. Ultimately, when evaluating the results of your recruitment, you should look at both the short-term and long-term results of recruitment. The short-term results include determining if the first four stages of recruitment were effective (objectives, strategy, activities, and interviews). The long-term results focus on whether or not a new employee meets the organization’s expectations or doesn’t meet the organization’s expectations, which could lead to either voluntary or involuntary turnover.

Realistic Job Previews

One of the major problems occurring post-hiring involves the expectations of the new employee. Social psychological research has demonstrated that when an individual’s expectations are not met, the individual will experience dissonance leading to a disliking of the event itself.Aronson, E., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1962). Performance expectancy as a determinant of actual performance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 65, 178–182. Paula Popovich and John Wanous explain that dissatisfaction is likely to occur when three conditions occur:

- the expectation is strongly believed in;

- the expectation concerns something of high personal value; and

- the individual feels personally responsible for the mistaken expectation (i.e., "I should have known" vs. "nobody's perfect").Popovich, P., & Wanous, J. P. (1982). The realistic job preview as a persuasive communication. Academy of Management Review, 7, 570–578, pg. 571.

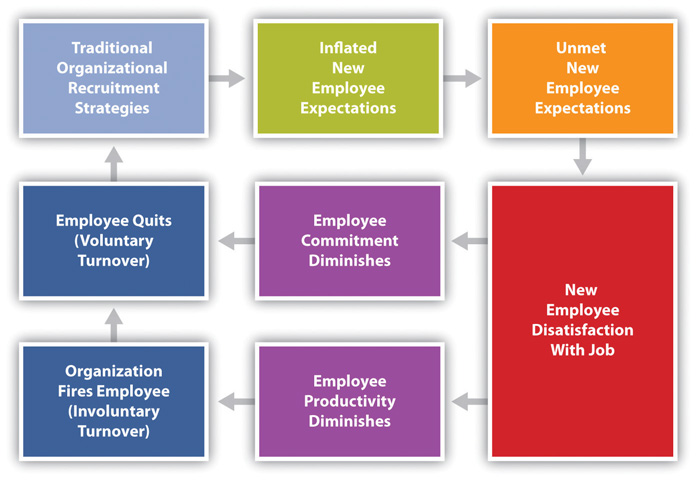

Whether one looks at hiring an individual from the organization’s perspective or looks at the new employee’s perspective, recruitment and hiring clearly meets all three of these conditions. Figure 10.2 "Problems with Traditional Organizational Recruitment" illustrates the problems associated with traditional recruiting strategies and how they leads to problems with expectations. First, organizations historically have done their best to make their organization look very positive and downplay or simply avoid any of the downsides of a particular job. Unfortunately, these traditional organizational recruitment strategies lead to inflated expectations on the part of a new hire. When that new hire comes face-to-face with the reality of working within an organization, he or she quickly becomes disillusioned because her or his initial expectations are not being met. With unmet expectations, the new employee will eventually become dissatisfied with her or his job. With employee dissatisfaction, two possible paths emerge, neither of them beneficial for the organization. First, a dissatisfied employee may decrease her or his commitment to the organization and simply start looking for a new job (voluntary turnover). Second, a dissatisfied employee’s productivity level may drop, causing the organization to become dissatisfied with the employee, which will lead to the employee’s firing (involuntary turnover). Of course, with either voluntary or involuntary turnover, the organization will be faced with recruiting a new employee and the cycle starts again.

Figure 10.2 Problems with Traditional Organizational Recruitment

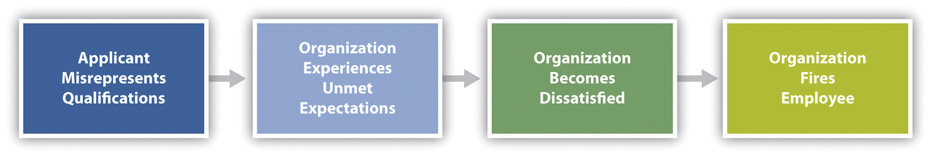

In addition to the organization misrepresenting who it is and how it functions, individual applicants can also misrepresent themselves. In Figure 10.3 "Misrepresentation of Qualifications" we see what happens when an individual applicant misrepresents her or his qualifications. In this case, the organization will be dissatisfied because the new hire cannot perform in the fashion the applicant said he or she could. As the organization’s expectations are unmet, the organization becomes dissatisfied, which will eventually lead to the individual employee’s firing (involuntary turnover).

Figure 10.3 Misrepresentation of Qualifications

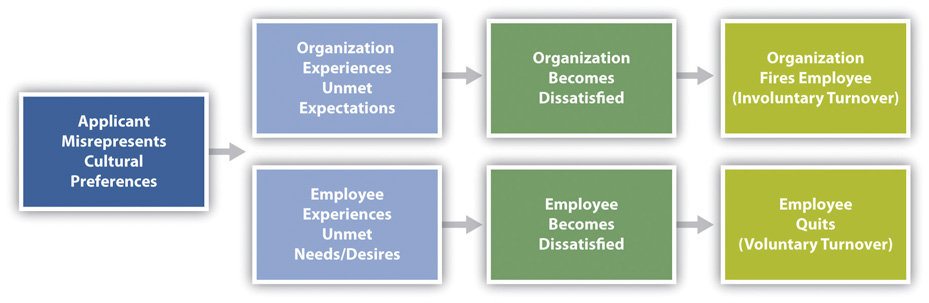

A second type of misrepresentation that can occur during the application process involves an individual employee’s cultural preferences. For example, maybe an individual applicant says he or she is all about teamwork during the interview, but in reality that applicant is a loner and prefers to work on projects alone. If this applicant is hired with the expectation that he or she will work on a number of teams, there will be unmet expectations on the part of the organization if the new employee quickly shows disinterest in teamwork. Furthermore, this new employee will experience unmet needs and desires for autonomy if he or she is constantly being forced to engage in teamwork. In the case of the organization’s unmet experiences, the organization will become dissatisfied, which will eventually lead to the organization firing the new employee. On the case of the individual employee, he or she will become dissatisfied with all of the pressure for teamwork and eventually look for another job that more accurately suits her or his cultural preferences.

Figure 10.4 Misrepresentation of Cultural Preferences

Although organizations can never completely prevent applicant misrepresentations, they can build in processes to prevent the outcomes associated with traditional recruitment processes. The basic premise of the realistic job preview is that new employees often have inaccurate perceptions about the positions for which they are applying. These expectations, as discussed above, lead to dissatisfaction on either the employee’s part or the organization’s part. To alleviate these inflated expectations, “it has been suggested that an employer should provide recruits with candid information concerning a job opening (i.e., information about both positive and negative job and organizational attributes).”Breaugh, J. A. (2008). Employee recruitment, Current knowledge and important areas for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 18, 103–118. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr:2008.07.003, pg. 106. Figure 10.5 "Realistic Job Preview Theory" illustrates why realistic job previews are effective. First, when a realistic job preview is given to applicants, the applicant will have more realistic expectations when he or she decides to accept a job offer. As that new employee enters into the organization, he or she will have more realistic expectations about the organizational culture and the day-to-day work that is expected. When an individual has realistic expectations, it’s much easier for these expectations to be met, which will lead to increased employee satisfaction and motivation. With increased employee satisfaction and motivation, your new employee will demonstrate greater organizational commitment and overall productivity. Ultimately, the goal of this process is to ensure that a new hire is less likely to be fired or quit.

To help us further understand the nature of realistic job previews, we are going to focus on three important aspects of this process. First, we will examine the theoretical basis for why realistic job previews work. Second, we’ll examine the importance of communication in the process of realistic job previews. Lastly, we’ll examine the research related to the outcomes of realistic job previews and their overall effectiveness.

Figure 10.5 Realistic Job Preview Theory

Two Theories for Realistic Job Previews

By this point, you may be wondering why realistic job previews (RJPs) are an effective tool when hiring new employees. Research has indicated two theoretical possibilities for why RJPs work.

Self-Selection Theory

The first theory explaining the effectiveness of realistic job previews is called the self-selection theory. In essence, self-selection theory argues that when applicants are faced with a realistic portrayal of an organization and what it would be like to work within an organization, the employee will have a more accurate understanding and more realistic expectations.Wanous, J. P. (1980). Organizational entry: Recruitment, selection, and As such, when an applicant decides to accept a job offer, he or she is knowingly opting to work within that organization (flaws included). In essence, people who feel that there is a good person-organization fit will self-select into the organization. Conversely, individuals who do not see the organization as a good person-organization fit will knowingly self-select out of working within that organization. Basically, self-selection theory posits that the more information someone has, the more accurately he or she can decide if an individual organization is somewhere he or she wants to work.

Inoculation Theory

The second major theoretical position researchers have posed for the effectiveness of RJPs is called inoculation theory. William J. McGuire originally created inoculation theory to explain how attitudes and beliefs are altered during persuasion attempts.McGuire, W. J. (1961). The effectiveness of supportive and refutational defenses in immunizing defenses. Sociometry, 24, 184–197. In the world of medicine, we often inoculate people using weakened strains of a virus and injecting them into an individual (called a vaccine). The weakened virus ultimately helps a host build up immunity to the virus itself. In the world of new employee hiring, the RJP functions as a vaccine, which ultimately prepares a new hire for the realities of working within the organization and her or his job duties. In essence, by presenting an RJP, an employer can help prepare a new hire in incremental steps for the day-to-day life the new hire is going to experience within the organization, so by the time the new hire starts the job, he or she has already built up “immunity.”

Communication & Realistic Job Previews

The realistic job preview (RJP) process is inherently a communicative one. One of the most important questions that should be asked is how will the message be presented. This message strategizing includes when the message will be presented, who will present the message, and the medium utilized. There are a number of different options that could be utilized: brochures, audio visual, human resource personnel, future coworkers, and virtual reality.

The first option involves using a brochure or new employee manual that realistically describes what it is like working for the organization. This brochure/manual should include details in a balanced fashion to ensure that the new employee is getting an accurate picture of what life would be like working within the organization. Unfortunately, brochures tend to be detached and simply are often either not read thoroughly or not read at all.

The second option that many organizations utilize for delivering an RJP is some form of audiovisual RJP. The most common audiovisual RJP is the video. Table 10.2 "Realistic Job Preview Videos" contains a list of just a handful of video RJPs that are available on the internet.

Table 10.2 Realistic Job Preview Videos

| Bank of America | http://careers.bankofamerica.com/rjp/ |

| Federal Air Marshalls | http://www.realisticjobpreview.net/fams/ |

| Transportation Security Administration (TSA) | http://www.realisticjobpreview.net/tsa_final.htm |

| Child Protective Services (CPS, State of AZ) | https://www.azdes.gov/main.aspx?menu=154&id=4297 |

| Quick Chek | http://www.quickchek.com/culture_video.asp |

| Pharmacy Technician | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=58mZFJADxWQ |

| Sears Sales Consultant | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NFUxEkX0hHE |

| Treatment Plant Equipment Operators | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hoPeWWmZoCA |

| Customer Service | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YRxJ9MJwBT4 |

| OwensCorning Home Experts | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lp4dZj0ZOF8 |

When you look at the various RJPs presented in Table 10.2 "Realistic Job Preview Videos", you’ll see a wide range of different types of jobs and different ways to present the information. Some videos have high production values and look like mini-movies (the TSA videos) and make the work look exciting while others include simple interviews with an employee who works for the organization in a specific position (Pharmacy Technician/Customer Service). Early research examining brochures and videos really didn’t find any differences between the two mediums and their actual effectiveness. Admittedly, most of the research on audiovisual techniques and RJPs occurred back in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

The third option listed above involves using the hiring personnel to describe the organization and the position. Although the hiring personnel may be great for describing the organization, he or she may not have the most accurate or up-to-date knowledge of what work life is like in every department. Research conducted by Alan Saks and Steven Cronshaw found that an RJP presented orally by an interviewer was better than a written RJP when predicting an individual’s attitude about the job and accepting a job offer. Furthermore, individuals who received the oral RJP found the organization to be more honest as a whole.Saks, A. M., & Cronshaw, S. F. (1990). A process investigation of realistic job previews: Mediating variables and channels of communication. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 11, 2210236.

Fourth, an organization could utilize an informal meeting with a current employee who works within the division the new hire will work in. No one really has a clearer perception of work life than someone actually involved in the same type of work the applicant will be required to do. Research conducted by Stephen Colarelli investigated using an incumbent bank teller to deliver an RJP during the hiring process as compared to a written RJP or no RJP at all. The research found that individuals who received the RJP from an incumbent bank teller were less likely to have quit the job after 2 or 3 months. In fact, Colarelli’s research found no difference in turnover rates between those who received the brochure and those who didn’t receive an RJP at all.

Lastly, many organizations actually utilize some form of virtual reality simulation for delivering RJPs. In essence, the virtual reality simulation is designed to present job applicants with scenarios that would resemble the actual working conditions the potential employees would face in a day-to-day working environment. These types of simulations may be great for jobs that are highly routinized (employees do the same thing day-in and day-out), but not so great for jobs that are more chaotic. These interactive simulations can not only provide the applicant with an RJP, but the simulations can be created in a fashion that demonstrates to the organization whether or not the applicant would be a good fit as well. Although applicants indicate that they appreciate the interactive quality of the simulations when determining whether to work somewhere,Murphy, J. P. (2012, April 13). Show, don’t tell—Job tryouts go virtual [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.shakercg.com/blog/tag/realistic-job-preview/ there really is no outcome data on the actual effectiveness of this new method.

Outcomes of Realistic Job Previews

Ultimately, the big question for most organizations relates to the effectiveness of realistic job previews in the prevention of voluntary and involuntary turnover. A number of research studies have attempted to determine whether a realistic job preview works in the manner discussed in Figure 10.5 "Realistic Job Preview Theory". In a study conducted by Jean Phillips that compiled the research results from 40 different studies examining realistic job previews, she found that RJPs did lead to lower initial expectations and lower levels of both voluntary and involuntary turnover.Phillips, J. M. (1998). Effects of realistic job previews on multiple organizational outcomes: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 673–690. However, the statistical relationships between RJPs and the outcome variables wasn’t exactly overwhelmingly strong. For this reason, David Earnest, David Allen, and Ronald Landis have cautioned that while RJPs are definitely effective, the actual return on their investment for an organization may not be high enough to warrant their utilization within a modern organization.Earnest, D. R., Allen, D. G., & Landis, R. S. (2011). Mechanisms linking realistic job previews with turnover: A meta-analytic path analysis. Personnel Psychology, 64, 865–896. In their study of 52 different research studies examining realistic job previews, the researchers found that an RJP increased new employee perceptions of organizational honesty, which in-turn actually impacted voluntary turnover. In essence, the researchers argued that an “RJP signals something about unobservable organizational characteristics such as organizational honesty, organizational support, and care for employees.”Earnest, D. R., Allen, D. G., & Landis, R. S. (2011). Mechanisms linking realistic job previews with turnover: A meta-analytic path analysis. Personnel Psychology, 64, 865–896; pg. 888. Although the overall outcomes for RJPs may not be the greatest organizational investment, they do help to moderately decrease both voluntary and involuntary turnover, so investing moderate amounts of organizational resources may still be worth the investment.

Key Takeaways

- The costs of recruiting can be quite extensive for organizations. Depending on the complexity of the job, costs can range from a few thousand dollars to hundreds of thousands of dollars to recruit a new employee, so effective recruitment is fiscally important for organizations.

- Breaugh, Macan, and Grambow created a five-stage model for explaining effective employee recruitment. Stage one, recruitment objectives, involves determining the basic objectives for a new position. Stage two, recruitment strategy, involves thinking through the most effective practices for locating and recruiting potential employees. Stage three, recruitment activities, involves the day-to-day process for recruiting potential applicants, allocating resources for recruitment, and crafting recruitment messages. Stage four, applicant interview, involves interview potential applicants in an effort to determine person-organization fit. Lastly, stage five, recruitment results, involves examining the effectiveness of the organization’s overall recruitment strategy post-hire.

- Traditional recruitment practices have led to a combination of unmet expectations on the part of both employees and organizations. When employees have unmet expectations, their productivity and commitment will diminish, which could lead to either voluntary or involuntary turnover. When the organization’s expectations are not met, the organization will be disgruntled with the new employee, which will lead to involuntary turnover.

- The goal of a realistic job preview is to provide potential applicants a complete picture of both the day-to-day work the applicant will be tasked with and explanation of the organization’s culture. The goal of a realistic job preview is to ensure that applicants have a complete picture of the working environment, which will lead to an increase in met expectations for both the new employee and the organization.

- Although there are a number of methods one can utilize to present a realistic job preview (e.g., written documents, videos, hiring personnel, virtual reality, etc.), research generally supports that the most effective tool involves a conversation with a current employee who occupies the same position.

- Realistic job previews have been shown to have many beneficial outcomes for organizations. First, realistic job previews lead to more accurate new employee expectations. Second, realistic job previews decrease both voluntary and involuntary turnover. Lastly, realistic job previews increase new hires’ beliefs that an organization is honest, which in-turn leads to decreased levels of voluntary and involuntary turnover.

Exercises

- You are in the process of hiring a new employee. You believe that a realistic job preview would be very important during the hiring process, but your boss doesn’t understand its importance. How would you go about framing your argument in terms of a realistic job preview’s financial impact on your organization?

- Table 10.2 "Realistic Job Preview Videos" provides a list of a wide range of realistic job preview videos. Select one of the videos and then answer the following questions. Do you think the realistic job preview is effective? Why or why not? How would you go about making this video more effective for new employees?

- You’ve been asked to sit down with a new employee who is taking over your current job (or most recent job). What information do you think would be most important to impart to this person in a realistic job preview? Why do you think that information is the most important? Do you think your supervisors would agree with your assessment of the position? Why or why not?

10.2 Socializing

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate among the three stages of socialization discussed by Fredric Jablin.

- Differentiate between vocational and organizational anticipatory socialization.

- Explain Fredrick Jablin’s three-step process for organizational entry and assimilation.

- Explain Alan Saks and Jamie Gruman socialization resources theory.

- List and describe the various tools organizations have for onboarding.

- Explain the relationship between communication and organizational socialization.

© Thinkstock

Organizational socializationThe process an organization utilizes to ensure that new members acquire necessary attitudes, behaviors, knowledge, and skills to become productive organizaitonal members. can be defined as the the process an organization utilizes to ensure that new members acquire necessary attitudes, behaviors, knowledge, and skills to become productive organizaitonal members. In essence, organizational socialization is a life-long process that individuals go through from childhood to retirement.Wanberg, C. R. (2012). Facilitating organizational socialization: An introduction. In C. R. Wanberg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of organizational socialization (pp. 17–21). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. In this section, we are going to examine the stages of organizational socialization, best practices for organizational socialization, and the importance of communication during socialization.

Stages of Organizational Socialization

To help us understand organizational socialization, we’re going to look at the basic stages of organizational socialization originally discussed by Fredric Jablin.Jablin, F. M. (1987). Organizational entry, assimilation, and exit. In F. M. Jablin, L. L. Putnam, K. H. Roberts, & L. W Porter (Eds.), Handbook of organizational communication: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 679–740). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.,Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 732–818). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Jablin proposed that organizational socialization can be broken into three distinct parts: anticipatory socialization, organizational entry and assimilation, and organizational disengagement/exit (Figure 10.6 "Organizational Socialization"). To help us understand socialization, we are going to explore the first two forms of socialization (anticipatory and organizational entry/assimilation) in this section and organizational disengagement/exit in the next section.

Figure 10.6 Organizational Socialization

Anticipatory Socialization

The first part of socialization is referred to as anticipatory socializationThe period of time before an individual actually joins an organization., or the period before an individual actually joins an organization. To help us understand anticipatory socialization, let’s examine the two types of anticipatory socialization discussed by Fredric Jablin: vocational and organizational socialization.Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 732–818). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Vocational Anticipatory Socialization

Vocational anticipatory socializationThe process an individual undertakes as he or she selects a specific job or career. refers to the process an individual undertakes as he or she selects a specific job or career. Pretty much from the moment you understand the world around you, you start being socialized into the world of work. Fredric Jablin explained that there are five influential groups that affect our role anticipatory socialization: family, media, peers, education, and previous organizational experience.

The first form of vocational anticipatory socialization comes from our families. Think back to your early childhood and you may have memories of your parents sitting around the dinner table sharing stories of their workdays. These stories from our early childhood influence us largely later in life when it comes to how we perceive work. The stories we hear from our parents actually influence how we understand what it means to work and how we perceive work life. Furthermore, our families actually instill in us attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, and values about work. Even something as simple as the chores you were required to complete growing up informed your understanding of what it meant to work. Later in life, your family encourages you academically and even helps to direct you towards specific occupations. Often this direction is intentional (e.g., your mother wants you to be a physician), but this direction can be unintentional as well (e.g., parents disparage their own line of work or specific occupations). Overall, our families have a great deal of influence on our perceptions of work and different occupations.

The second most pervasive socializer of work today is probably the media. From the earliest moments most American children can sit up, they are consuming one form of media or another. Even children’s television shows like Sesame Street, Thomas and Friends, and Bill Nye—The Science Guy illustrate various occupations, which can have a profound effect on how children view the world of work. Children’s books also can have a direct impact on how people come to understand what work is. The reality is children are greatly influenced by the media, so it should be no surprise that these early impressions of what it means to work learned through the media impact our understanding of the work world. Obviously, as we grow older, we come to realize that these portrayals are often inaccurate, but this early learning still sticks with us and influences our future job and career selection decisions. However, Susan Barber warns us that these portrayals can also lead to unrealistic expectations of what the work world really looks like.Barber, S. (1989). When I grow up: Children and the work-world of television. Media and Values, 47, [online reprint]. Retrieved from http://www.medialit.org/reading-room/when-i-grow-children-and-work-world-television Too often television shows depict high-income jobs (e.g., lawyers, doctors, business executives, pop stars, etc.), while more blue-collar jobs are left completely out of the work landscape on television (e.g., carpenters, electricians, plumbers, etc.). Furthermore, there is a general tendency in a lot of media portrayals to depict occupations where the income earners are making a considerable more amount of money than the average family in the United States. These inflated expectations often persist into the college years.

The third form of vocational anticipatory socialization comes from our immediate peer group. As we all know, peer-influence is a very important part of growing up and continues to be important into adulthood. In a fashion similar to how we learn from our families, our peers influence our attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, and values about work. Our peer groups growing up help reiterate what types of occupations are deemed desirable and which ones should be avoided. Furthermore, we also learn about the world of work by listening to our peers’ stories of their own work experience or the experiences of our peers’ families and friends. These stories help to further solidify our perceptions about the world of work beyond that of our immediate family members.

The fourth form of vocational anticipatory socialization comes from our education. Not surprisingly, education is another very important factor to consider when looking at the landscape of how people are socialized. In fact, our educational system (just like the media) tends to overemphasize certain types of occupations. In an interesting study conducted by Fredric Jablin,Jablin, F. M. (1985). An exploratory study of vocational organizational communication socialization. Southern Speech Communication Journal, 50, 261–282. he found that classroom activities, discussions, and textbooks tended to overemphasize specific occupations while downplaying other occupations. In addition to this subversive socialization, schools often expect students to write research reports or give oral presentations about possible careers. Furthermore, in public education there does tend to be an over-emphasis on the importance of attaining a college degree.Kramer, M. W. (2010). Organizational socialization: Joining and leaving organizations. Malden, MA: Polity. If you look at the United States Census data from 2010, a very interesting picture emerges.United States Census (2010). Educational attainment by selected characteristics: 2010. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0232.pdf In the United States, 19.4 percent of the population has a bachelor’s degree and an additional 10.5 percent has an advanced degree, so rough 30 percent of the population has some form of advanced education past an associate’s degree. When one analyzes the data, people with just a bachelor’s degree make an average of $17,000 dollars per year more than those with an associate’s degree (9.1% of the US population) and $36,464 more on average than those who do not have a high school diploma (12.9% of the US population). However, our educational system is clearly designed to streamline students towards those occupations that involve advanced degrees that will not be attained by 70 percent of the actual population.

The final form of vocational anticipatory socialization comes from previous organizational experiences we’ve personally had. Whether you’ve worked as a cashier at a local grocery store, helped run your parent’s farm, or were just an active member of your local church growing up, we all have previous organizational experience that influences how we view the nature of organizations. Whether you’ve had actual work experience or voluntary associations within the context of an organization, these experiences form our perceptions of how organizations function and what it means to work. Any organizational experience helps you form attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, and values about work. One of the reasons internships are often pushed in higher education today is to ensure that students not only get a taste of an occupation that may interest them, but the internship experience helps students develop interpersonal skills in the workplace while developing a work ethic that will become very important as the student enters the job market.

Organizational Anticipatory Socialization

In addition to vocational socialization, there is a second form of anticipatory socialization that needs to be addressed: organizational anticipatory socialization.Kramer, M. W. (2010). Organizational socialization: Joining and leaving organizations. Malden, MA: Polity. Organizational anticipatory socializationThe process and individual goes through as he or she attempts to find an organization to join. is the process an individual goes through as he or she attempts to find an organization to join. According to Michael Kramer, we can break the organizational anticipatory socialization into two basic processes: recruiting and reconnaissance and selection. Kramer, M. W. (2010). Organizational socialization: Joining and leaving organizations. Malden, MA: Polity.

The recruiting and reconnaissance process and the selection process involves all of the steps discussed previously in Figure 10.1 "Model of Employee Recruitment". When we look at this process from the perspective of the applicant, we see that applicants have to find job advertisements or be approached by corporate recruiters. The applicant needs to ascertain whether the job description is a good fit for her or his educational background, skill set, and cultural preferences. During the organizational anticipatory socialization stage, both the applicant and the organization are making determinations of person-organization fit.

Organizational Entry & Assimilation

The second major step in organizational socialization involves the entry and assimilation of new organizational members. Fredrick Jablin proposed a three-step process when attempting to understand organizational entry and assimilation: preentry, entry, and metamorphosis. Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 732–818). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Preentry

The first step in organizational entry is referred to as preentryThe period of time after someone has been asked to join an organization but before he or she is actually working within the organization., or the period of time after someone has been asked to join an organization but before he or she is actually working within the organization. Jablin pointed out that there are three important issues that arise during the preentry stage. First, one must consider the types of messages a new employee receives from the organization prior to starting work. These messages could include realistic job previews or “surprises.” In this context, there could be either negative surprises, messages that are contradictory to what was discussed in the hiring process (e.g., work schedule, benefits, organizational expectations, etc.), or there could be positive surprises, messages that are pleasant and demonstrate positive aspects of working within the organization (e.g., expressions of caring, expressions of honest, expressions of organizational justice, etc.).

Second, new employees should be aware of how current organizational members view the new employee. The communicative strategies involved during this period generally involve impression management. Impression managementThe process (either conscious or unconscious) where an individual deliberately attempts to influence the perceptions and opinions of others. is the process (either conscious or unconscious) where an individual deliberately attempts to influence the perceptions and opinions of others. In this case, new organizational members attempt to form impressions about who they are as people and workers in the minds of new coworkers and supervisors. This could involve touting one’s previous work successes in an effort to bolster one’s credibility or purposefully self-handicapping oneself (e.g., “I’m a little weak when it comes to using a spreadsheet.”) in an effort to downplay organizational expectations.

Lastly, Jablin points out that the preentry period is also important to current organizational members who “converse about and make sense of new hires during this period, and in particular how they socially construct or create a reputation for newcomers in everyday conversations.”Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 732–818). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; pg. 753. In essence, once someone is hired there is a period of time when current organizational members attempt to create an image about the new hire. This image includes both how this new hire will fit within the current structure of the organization and the new hire’s reputation. The reality is, people in an organization will talk about new hires in an effort to reduce some of the uncertainty that is bound to come with a new organizational member. Unfortunately, the reputations that are generated could easily inflate the new hires’ skills making it harder for the new hire to actually meet the unrealistic expectations created. In other words, it’s always important to attempt to get the pulse of how organizational members view you when you first start the job in an effort to correct any misconceptions people may have.

Entry

The second stage of organizational entry and assimilation involves the actual process of entering the organization as a new member. The goal during the entry period is to help new members assimilate themselves within the organizational culture. According to Fredric Jablin, organizational assimilation involves the process an individual goes through as he or she is acclimating her or himself within an organization’s culture.Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 732–818). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Ultimately, the entry period involves two interrelated processes: intentional socialization efforts and individualization. Jablin, F. M. (1987). Organizational entry, assimilation, and exit. In F. M. Jablin, L. L. Putnam, K. H. Roberts, & L. W Porter (Eds.), Handbook of organizational communication: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 679–740). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

First, during the entry period, organizations attempt to help new employees understand the organization’s culture and the work expectations for the new employee. Often this process is formal and involves some kind of new employee training or probationary period while the new employee “learns the ropes.” This process includes helping employees understand both the rules and norms of the organization. The rulesThe explicit dictates that govern employee behavior within the organization. of an organization are the explicit dictates that govern employee behavior within the organization. For example, maybe there is a formal dress policy. One of our coauthors worked for a hospital that had very strict dress policies. One of the policies dictated the necessity of closed-toed shoes (no sandals or flip-flops). Another policy spelled out what happened when paperwork was not submitted on time. NormsThe informal expectations about how new employees should behave within the organization., on the other hand, involve the informal expectations related to how new employees should behave within the organization. Norms are not formal policies, but they dictate how people behave in much the same way. For example, maybe Monday through Thursday everyone is expected to wear a business suit, but there is a norm that people are allowed to dress in business casual clothes on Friday. This allowance for casualness on Fridays may not be expressly written anywhere in the formal employee manual (aka rule), but it may be very much the norm of how people behave within the organization.

In addition to acclimating a new employee to the organization, new employees often attempt to negotiate the new work environment to better fit their individual attitudes, skills, and cultural values. One of our coauthors is very much not a morning person. When he entered into his latest job, one of the things he negotiated was not teaching classes before noon. Thankfully, his organization was flexible and allowed for this individualization of the job to better meet his preferences for a teaching schedule. However, individualization can become very problematic if the new hire attempts to morph into something he or she was not hired for. Imagine an organization hires a new public relations expert only to discover quickly that the person really is more interested in marketing and not public relations. Although these may be related industries within the organization, having someone become something they were not hired to be will quickly lead to organizational dissatisfaction.

Metamorphosis

The final stage of organizational entry and assimilation involves the metamorphosis stage. The concept of metamorphosis refers to the profound change that occurs when someone goes from one stage to the next in life. In the organizational world, metamorphosisWhen an individual transforms her or himself from a new organizational member to an established member of the organization. occurs when an individual transforms her or himself from the “new kid on the block” to an established member of the organization. Obviously, metamorphosis does not happen quickly. Often these transitions happen rapidly (e.g., success of one’s first big project), but more often these transitions happen over a long period. Often people wake up one day only to realize that they truly are part of the organization and its culture. Furthermore, this process is not a stagnant one. As people move in and out of new positions within an organization, they may experience the process of entry and assimilation all over again. For example, when someone goes from being a low-level employee to mid-level management, the individual may still work within the same organization but her or his perception of the organization and its functions may drastically alter with the new position.

Overall, entering into an organization and assimilating is not something that happens overnight. Entering and assimilating is a process that takes time both for new organizational members and those members who already exist within the organization itself. So, you may be wondering, how can you make your socialization process smoother when you enter into a new organization? Virginia Peck Richmond and James McCroskey proposed ten communicative behaviors to avoid during organizational entry (Table 10.3 "Dead on Arrivals").Richmond, V. P., & McCroskey, J. C. (2009). Organizational communication for survival: Making work, work (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; pgs. 192–193. Richmond and McCroskey termed these behaviors DOA or “dead on arrival” to indicate that those who engage in the behaviors discussed in Table 10.3 "Dead on Arrivals" generally will not have a very long life in an organization if they communicate in this manner.

Table 10.3 Dead on Arrivals

| 1. DOAs hold supervisors solely responsible for their growth and motivation. |

| 2. DOAs often think they know it all and refuse assistance from other employees and their supervisors. |

| 3. DOAs make statements about how behind the times the organization is and how out of touch the organization is. |

| 4. DOAs want all the rewards available in the system without paying any dues or putting in the time to earn them. |

| 5. DOAs often deviate from the organizational norms. |

| 6. DOAs enjoy arguing over insignificant issues simply to get attention. |

| 7. DOAs are constantly “poking their noses” into other peoples’ business. |

| 8. DOAs usually step on the toes of the people in the good old boys/girls clubs. |

| 9. DOAs usually will talk negatively about their boss and their co-workers behind their backs at social gatherings or other functions outside the immediate work unit. |

| 10. DOAs try to get things accomplished without following the proper communication channels in the organization. |

Methods of Socialization

Now that we’ve explored the basic steps involved in the organizational entry and assimilation process, let’s explore a number of issues related to socialization in the workplace. To help us explore methods of socialization, we’re going to first explore socialization resources theory, then we’ll examine the toolbox that most organizations use for assimilating new members, and lastly we’ll discuss the communication strategies that new employees and organizations employ during the assimilation process.

Socialization Resources Theory

Alan Saks and Jamie Gruman have recently created an integrated approach for understanding effective organizational socialization, which they have deemed socialization resources theory.Saks, A. M., & Gruman, J. A. (2012). Getting newcomers on board: A review of socialization practices and introduction to socialization resources theory. In C. R. Wanberg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of organizational socialization (pp. 27–55). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. The basic premise of socialization resources theory is that during a period of stress (e.g., entering into a new organization), the availability of resources to that individual will determine her or his ability to cope with the stressful situation, which will in-turn help the individual adjust and successfully socialize within the organization. To help explain how effective socialization works, Saks and Gruman developed a list of seventeen resource dimensions that have been shown in both the academic and practitioner literatures on organizational socialization to facilitate effective organizational socialization. Table 10.4 "Dimensions of Socialization Resources Theory" provides an overview of the 17 dimensions.

Table 10.4 Dimensions of Socialization Resources Theory

| SRT Dimension | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|

| Prior to Entry | ||

| 1. | Anticipatory Socialization | To what extent does an organization reach out to new members prior to organizational entry in an effort to make the new member feel welcome? |

| Immediately After Entry | ||

| 2. | Formal Orientation | What is the nature of a new employee’s orientation (e.g., length, delivery method [face-to-face/online], what types of activities, & who is involved)? |

| 3. | Proactive Encouragement | To what extent are new employees encouraged to actively meet new people, ask questions, and develop organizational relationships? |

| 4. | Formal Assistance | Are new hires assigned formal mentors to help with organizational socialization? |

| Social Capital Resources | ||

| 5. | Social Events | To what extent does an organization hold formal social events (e.g., happy hours, lunches, parties, etc.)? |

| 6. | Socialization Agents | To what extent do organizational insiders reach out to new hires informally? |

| 7. | Supervisor Support | Do supervisors reach out to new employees demonstrating caring and support? |

| 8. | Relationship Development | Does the organization provide the time and space for new hires to meet and develop relationships with other organizational members? |

| Work-Related Resources | ||

| 9. | Job Resources | Do new hires have the necessary resources (equipment and space) to perform their jobs? |

| 10. | Personal Planning | To what extent does an organization clearly communicate work expectations to the new hire? |

| 11. | Training | Does the organization provide relevant programs to provide a new employee necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to effectively perform her or his job? |

| 12. | Assignments | Are initial assigned tasks relevant to why the person was hired and provide some level of challenge and reflect the expectations of future task assignments? |

| 13. | Information | To what extent does an organization clearly communicate information about the organization and its expectations? |

| 14. | Feedback | Do supervisors provide timely and accurate feedback to new employees related to organizational values and task performance? |

| 15. | Recognition & Appreciation | Are new employees praised for their effort and performance? |

| Follow-Up Period | ||

| 16. | Follow-Up | Does the organization have processes in place to follow an employee’s progression after a formal orientation period has ended? |

| 17. | Program Evaluation | To what extent and how often does an organization track the effectiveness of its organizational socialization programs? |

The resources discussed in Table 10.4 "Dimensions of Socialization Resources Theory" really are considered the best practices in organizational socialization. As such, this list can be very effective when diagnosing an organization’s current socialization practices. In essence, an organizational consultant could utilize this list of resource dimensions in an effort to determine where an organization succeeds and needs improvement in the organization’s socialization efforts.

Tools for Assimilating New Members

As we’ve discussed above, assimilating new organizational members into the culture of the organization is very important. Organizational scholars commonly refer to the practice of assimilating new members as onboarding. OnboardingThe process of welcoming and orienting new organizational members to facilitate their adjustment to the organization, its culture, and its practices. refers to the process of welcoming and orienting new organizational members to facilitate their adjustment to the organization, its culture, and its practices. Klein and Polin argue that socialization is what happens within a new employee; whereas, onboarding processes are put in place by management and human resource departments to help facilitate socialization.Klein, H. J., & Polin, B. (2012). In C. R. Wanberg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of organizational socialization (pp. 267–287). New York, NY: Oxford University Press; pg. 268. As such, over the years a number of different types of onboarding programs were established. To help us understand the possible tools that organizations can utilize to facilitate onboarding, we are going to examine briefly orientation programs, training programs, and formal mentoring programs.

Orientation Programs

The first common tool used by organizations during an onboarding program involves some kind of formal orientation program. The general goal of an orientation program is to facilitate the general understanding of the organization and one’s expected duties within the organization. New employee orientation programs can generally last from three hours to multiple days depending on the complexity of the organization and the duties expected by the new hire. Common topics during orientation programs include the history of the organization, the mission/vision of the organization, organizational rules, benefits of working for the organization, and other topics deemed necessary by either the organization or local, state, and federal government agencies.

Training Programs

The second way organizations go about onboarding new members is through training programs. The goal of formal training programs during the onboarding process is to facilitate the acquisition of necessary skills and knowledge needed complete one’s job. Although there are some training programs that have broad organizational appeal (sexual harassment training, workplace bullying training, crisis management training, etc.), most of the training targeted towards newcomers is position-specific training. For example, maybe your position requires you to utilize Microsoft’s Project Management software. To help you prepare to complete your training, your organization may send you to a workshop or possibly get you a subscription to an online training program like Lynda.com or TotalTraining.com. The goal of training programs is to help get new members up to speed as fast as humanly possible.

Formal Mentoring

As discussed in Chapter 7 "Leader and Follower Behaviors & Perspectives", mentoring is the transfer of experience or knowledge from a senior individual (the mentor) to a junior individual (the mentee or protégé) in an effort to help the junior individual learn the ins and outs of organizational life. To help with onboarding, many organizations establish formal mentoring programs where new members are assigned a mentor upon hiring who is supposed to help acclimate the new member to the organization. Formal mentoring is really only as successful as the mentors who participate in the mentoring programs. If the mentors are too busy or unconcerned with the new hires, then the formal mentoring program will not be overly effective. On the other hand, if organizations taking mentoring seriously and provide support and training for potential mentors, formal mentoring programs can be very successful. Notice this is not the same type of mentoring discussed in Chapter 7 "Leader and Follower Behaviors & Perspectives" when we discussed informal mentoring.

Communication & Socialization

One of the most important parts of socialization (and onboarding) involves the type, quantity, and quality of the communication sent and received by new employees during the socialization process. Fredric Jablin explained that there are four primary functions for communication during the socialization process: information giving, information seeking, relationship development, and role negotiation.Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 732–818). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Information Giving

The first function of communication during socialization involves information giving. Information givingThe types of information a new employee provides to coworkers and superiors during organizational entry. refers to the types of information a new employee provides to coworkers and superiors during organizational entry. How much and what one shares with others is extremely important during the initial periods of a new job. Some employees are hesitant to provide any personal information to coworkers and supervisors until after they get to know them, but information giving is one of the easiest ways to help alleviate any fear coworkers or supervisors may have about a new hire. In a study conducted by Fredric Jablin, he found that 25.6% of a newcomer’s communication was information-giving.Jablin, F. M. (1984). Assimilating new members into organizations. In R. N. Bostrom (Ed.), Communication Yearbook 8 (pp. 594–626). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Jablin further describes four basic types of information given by new employees: evaluative work, evaluative nonwork, descriptive work, and descriptive nonwork.Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 732–818). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

The first form of information giving was labeled evaluative work and consists of information shared regarding one’s like or dislike of the job itself. This could include discussions of unmet expectations or needs. The amount of stress one feels on the new job. One’s overall level of motivation or job satisfaction with the new job. All of these forms of information giving are evaluative in nature and centered around the job itself.

Evaluative nonwork, on the other hand, examines the types of judgmental information given by a new hire about issues that are outside the confines of the organization itself. These could include evaluative statements related to other organizations an individual belongs to (e.g., social clubs, churches, etc.). These statements could also examine how the job affects one’s participation in nonwork activities. Again, all of these types of information giving focus on judgments of nonwork activities.

Next, you have descriptive work information giving, which focuses on information provided by a new employee related to one’s understanding of a specific organizational or job task (e.g., task performance, task goals, and task instructions). Again, the purpose of this information is not to judge what is occurring within the organization, but to provide information to others about the specific tasks.

Lastly, individuals can provide information that describes nonwork activities. Generally, these forms of information relate to individual’s hobbies, family life, and personal goals. For example, maybe a new coworker went to the movies last night and tells you about the plot. Maybe another new coworker was recently married and shows you pictures of her or his wedding. Both of these examples involve new employees simply providing organizational members more information about the new employee in an effort to help older organizational members learn about the new employee.

Information Seeking

The second type of communicative behavior that occurs during organizational socialization is information seeking. Information seekingA new employee’s proactive search for information. involves a new employee’s proactive search for information. In a study conducted by Vernon Miller and Fredric Jablin, the researchers observed seven basic tactics that new employees utilize when attempting to seek information.Miller, V. D., & Jablin, F. M. (1991). Information seeking during organizational entry: Influences, tactics, and a model of the process. Academy of Management Review, 16, 92–120. The seven tactics can be found in Table 10.5 "Information Seeking Tactics".

Table 10.5 Information Seeking Tactics

| 1. Overt: Asking for information in a direct manner. |

| 2. Indirect: Getting others to give information by hinting and use of noninterrogative questions. |

| 3. Third Party: Asking someone else rather than the primary information target. |

| 4. Testing: Breaking a rule, annoying the target, and so on and then observing the target’s reaction. |

| 5. Disguising Conversations: Use of jokes, verbal prompts, self-disclosure, and so on to ease information from the target without the person’s awareness. |

| 6. Observing: Watching another’s actions to model behavior or discern meanings associated with events. |

| 7. Surveillance: Indiscriminately monitoring conversations and activities to which meaning can be retrospectively attributed. Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 732–818). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; pg. 770. |

Relationship Development

The next purpose of communication during organizational assimilation involves the development of relationships with coworkers and supervisors. As discussed earlier in this chapter, we spend a considerable amount of time in our lives at work. Of that time we spend at work, a great deal of it involves interacting with our coworkers and supervisors. As such, one of the primary reasons we communicate with people when we first enter into an organization is to develop relationships (both formal and friendly) with the people in our workplace. Although we may not become “best” friends with our coworkers and supervisors, most of us will make friends at work. In fact, research examining friendship in the workplace has demonstrated that organizations that encourage the development of workplace friendships will have employees who are more satisfied, motivated, and productive.Nielsen, I. K., Jex, S. M., & Adams, G. A. (2000). Development and validation of scores on a two-dimensional workplace friendship scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60, 628–643.

Role Negotiation

The final reason for communication during the entry stage of organizational socialization involves role negotiation. Earlier in this chapter we discussed the idea of how new employees attempt to individualize their work experience. Role negotiation is a part of this individualization. Although employees often wait an appropriate amount of time before starting the individualization of their workplace, eventually a new employee will have built up enough credibility to start conversations with coworkers and supervisors to individualize their workplace. Role negotiationsThe process that occurs when an employee attempts to negotiate with her or his supervisor about communicated expectations. occurs when an employee attempts to negotiate with her or his supervisor about communicated expectations. When people are hired, there are clearly established expectations related to the job in question (sometimes called a job description). These expectations can involve everything from the tasks one completes to one’s place in the organizational hierarchy. When one attempts to engage in role negotiation, the new employee is attempting to alter her or his supervisor’s expectations in an effort to alter or individualize the new employee’s work life.

Key Takeaways

- Fredric Jablin articulated three basic stages of organizational socialization: anticipatory socialization, organizational entry/assimilation, and organization disengagement/exit. Anticipatory socialization is the period of time before an individual enters into an organization. Organizational entry/assimilation is the period of time that occurs from the moment an individual enters an organization to the moment he or she becomes an established member of the organization. Organizational disengagement/exit is the period of time when an individual has decided to leave an organization to the moment he or she actually makes her or his exit.

- Vocational anticipatory socialization is the process an individual undertakes as he or she selects a specific job or career. From our earliest moments in life, our families, peers, teachers, and organizational experiences socialize us and teach us about the world of work. Organizational anticipatory socialization, on the other hand, is the process and individual goes through as he or she attempts to find an organization to join.