This is “Organizational Identity and Diversity”, chapter 8 from the book An Introduction to Organizational Communication (v. 0.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 8 Organizational Identity and Diversity

Who Are “We”?

© Thinkstock

It’s a weeknight, you’ve worked late, and you don’t feel like making dinner when you get home. So you decide to grab a bite on the way. Having opted for fast food, you consider the choices. There’s the leading national burger chain; if you go there, then you know exactly what you’ll get no matter which location you visit. One rival burger chain, however, works hard at promoting a reputation for higher-quality meat, while another advertises higher-quality sandwiches. Then there are the alternatives to hamburgers: a national chain that proffers a home-style menu; another that promotes chicken as a kind of anti-burger; yet another that specializes in Mexican-themed foods. Among all these different chains, their corporate identities have been respectively conveyed through the symbols of a clown, a king, a redhead, a colonel, a cow, and a dog.

This scenario highlights some basic issues of organizational identity. Each of the organizations referenced above is trying to foster a unique identity in a world already saturated with competing messages. George Cheney and Lars Christensen likened this challenge to that of a shipwrecked castaway who, after putting a message in a bottle, goes to throw it in the ocean but “cannot see the water [because] it is covered with messages in bottles.”Cheney, G., & Christensen, L. T. (2001). Organizational identity: Linkages between internal and external communication. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The nmew handbook of organizational communication (pp. 231–269). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; pg. 240. To convey its identity to the world, however, the organization must first establish its own firm sense of who “we” are. And because “we” means everyone, then organizational identity is not just a corporate matter to be decided by management. To carry off its corporate image, individual organization members—from executives to employees—must buy into and identify with the organization.

Then, too, if organizational identity starts with members and is then projected to others, the traditional distinction between “external” and “internal” communication becomes blurred. Communication activities—including advertising, marketing, and public relations—that convey an organization’s identity to external audiences are, in fact, the flip side of internal communication activities by which members make sense of who “we” are. The concept of identity casts organizational communication as a dialectic: organization members negotiate who “we” are; that identity is negotiated with the organization’s environment; and then the organization adjusts its identity in response to how it is perceived. To return to our opening scenario, the external activities by which each fast food chain communicates its identity to consumers cannot be divorced from the internal communications by which that same identity is fostered among members of each organization. Thus, the basic issues of organizational identity can be expressed by a series of questions:

- How do communications between members of an organization develop a sense of who “we” are?

- As this sense is developed, how is organizational identity maintained and transmitted to new members?

- How is this identity conveyed to persons who are, at least in a formal sense, outside the organization?

The first question is of greater interest to managers of new organizations, while the second and third are concerns for managers of established organizations. Indeed, organizational identification is a prime corporate objective as management strives to cultivate employees who feel strongly attached and loyal to the organization and its values. At the same time, leaders engage in impression management to engender positive feelings among the various publics—from customers, to shareholders, to the media—on whose goodwill the organization depends. Nevertheless, the managerial drive to maintain a stable corporate identity and foster strong organizational identification among employees has certain risks. Too much homogeneity can cause an organization to be set in its ways and respond too slowly to changes in the marketplace; for example, IBM ruled the computer world through the 1980s but its organizational identity as a maker of “business machines” may have caused it to miss the personal-computer revolution. Moreover, too much homogeneity in a workforce can lead to groupthink and deny organizations the diverse mix of employees and viewpoints that boosts creativity and leads to better decisions.

In this chapter, then, we have paired identity and diversity as two aspects of organizational life that exist in a tension which must be successfully balanced. This is true for leaders who must manage public impressions about the organization and, simultaneously, who must manage employees so that they identity sufficiently with the organization to support the desired corporate identity. But this need to manage the tension between identity and diversity is also true for individual organization members.

Since the Industrial Revolution and then with accelerating force in the twentieth century, organizations have become major sources of personal identity for many people. In traditional societies, the bonds of local community and local authority supplied stable roles for people. In modern societies, however, people derive a major part of their identities from the organizations with which they affiliate. Perhaps you know people who identify so completely with an organization that its values form their personal sense of moral duty. Perhaps you have experienced this feeling yourself about a sports team on which you played, a church or mosque to which you belong, a club that you joined, or even the college you now attend. For individuals, the tension between organizational identity and diversity is sometimes called the work-life conflict. At work you want to be a valued “team player” who helps to achieve organizational goals, and yet you also want to retain your own identity. First, you desire to give your employer the advantage of your own unique perspectives; second, you understand the personal need to “get a life.”

Then, too, the social contract between employers and employees has changed over the past two generations in response to globalization (see Chapter 6 "Organizational Communication Climate, Culture, and Globalization"). Until the 1970s people generally believed that employees who strongly and loyally identified with their organizations would be rewarded with job security and a reasonable expectation of a lifelong career. Today, employees realize they have no such guarantees and do not expect to spend their entire adult lives working for a single company. Under this new social contract you must balance the level of organizational identification needed to do your work effectively and gain satisfaction from your employment, with the knowledge that you must build a personal “brand” that is separate from your current organization. Why? Chances are that you will be working for another company someday.

8.1 Identity and the Organization

Learning Objectives

- See how different approaches to the nature of organizations lead to different perspectives on organizational identity.

- Understand the concept of organizational identity, both its roots in theories of individual identity and how the literature on organizational identity has developed to the present.

- Differentiate between organizational identity, organizational culture and organizational image, and grasp the dynamic relationships between them.

- See how organizational identity can be unstable and mutable, changing and adapting in response to external feedback or events that challenge an organization’s image and reputation.

- Understand the danger of self-referential auto-communication and the ethical challenges posed.

© Thinkstock

Because it raises questions of ontology, epistemology and axiology (see Chapter 4 "Modern Theories of Organizational Communication"), the concept of identity evokes debate among organizational communication scholars which reflects larger controversies in the field. One review noted that, while “interest in concepts of organizational identity has grown” and “the literature is expanding rapidly,” the notion “has been subjected to much scrutiny and debate, [and] definitions and conceptualizations of the topic remain essentially contested.”Seidl, D. (2005). Organizational identity and self-transformation: An autopoietic perspective. Burlington, VT: Ashgate; pg. 67.

From a postmodern perspective the very concepts of identity and individuality are suspect. Where Western philosophy views each person as a self-contained unit who is in charge of his or her intentions, postmodernists regard each person as “site” where the flux of larger historical and cultural discourses conditions our thoughts and intentions. From a critical perspective, on the other hand, the concept of identity is entangled with societal structures of power that “colonize” individual consciousnesses in order to make the dominant order seem normal and natural. These two approaches, postmodern and critical, may also be extended from personal identity to organizational identity. Postmodernists would question the assumption that organizations have autonomous identities and instead view organizations as sites where larger historical discourses compete. And critical scholars might analyze how management cultivates an organizational identity that legitimates its own interests and, by making those interests seem the natural order of things, brings workers under its control and domination.

The concept of organizational identity also raises a question similar to one we explored in Chapter 6 "Organizational Communication Climate, Culture, and Globalization" about organizational culture. In other words, is organizational identity just one attribute, among a set of many different attributes, that an organization “has,” a variable that leaders can “manage” to boost performance? (This would be the postpositive or functionalist view.) Or should identity be seen as a phenomenon that emerges from members’ communicative interactions, and thus part of what an organization “is”? (This would be the interpretive view.) Table 8.1 "Approaches to Organizational Identity" below suggests how the four approaches to organizations—postpositive, interpretive, critical, and postmodern—might view organizational identity.See also Gioia, D. A. (1998). From individual to organizational identity. In D. A. Whetten & P. C. Godfrey (Eds.), Identity in organizations” Building theory through conversations (pgs. 17–31). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Table 8.1 Approaches to Organizational Identity

| Approach to Organizations | View of Organizational Identity |

|---|---|

| Functionalist | Identity is one of the attributes that an organization “has” and may be managed to improve organizational performance |

| Interpretive | Identity is an emergent phenomenon that arises from the social and communicative interactions between organization members |

| Critical | Identity is a tool that management can manipulate to universalize its interests (i.e., equate “company interests” with managerial interests) |

| Postmodern | Identity is a modern conceit; an organization does not have a unique “self” for its intentions are conditioned by larger historical discourses; if anything, organizations are fragmented into multiple identities |

We will explore postmodern and critical views of organizational identity in greater detail later in the chapter. But we start with an interpretive perspective since the concept of organizational identity originated in that tradition. To get a grip on the concept, we begin with two basic metaphors: the organization as a biological organism, and the organization as a person. The first metaphor will help us grasp the organizational aspect of identity and the second to comprehend the communicative aspect.

Two Metaphors

As we learned in Chapter 4 "Modern Theories of Organizational Communication", systems theory is based on the metaphor that an organization can be likened to biological organism. From that perspective, we can understand how a living thing must somehow maintain a boundary between itself and the environment. The boundary may be permeable as resources pass between the organism and the environment. But if there is no boundary then the organism would cease to exist as an identifiable entity. Now let us apply the metaphor to organizations.

We do not speak of a “civilization” as an “organization”; a civilization is, practically speaking, unbounded. On the other hand, a basic function of any organization is to continually organize a boundary between itself and its environment. Establishing a boundary is accomplished in two ways. First, an organization sets up formal hierarchies: for example, a company adopts a form of ownership and a corporate structure, sets hiring and firing procedures for determining who can be an employee, and establishes locations where work takes place. But since all organizations establish formal boundaries, something is still missing: What makes “us” different from “them”? Thus, a second way that an organization creates and maintains a boundary is by developing a sense of “who we are” that distinguishes it from other organizations. This second type of boundary is one way to define the concept of organizational identity. From this standpoint, then, one basic organizing function of an organization is to continually organize an identity that distinguishes it from the environment of other organizations.

Our second metaphor likens an organization to a person. More than a century ago, Charles Horton Cooley asserted that identity is constructed through language and has both an individual and a social aspect; indeed, identity is partly shaped as each of us mentally constructs a looking-glass selfA term coined by Charles Horton Cooley, the looking-glass self is a mental image of how you think others perceive you and which drives the social aspect of your self. based on how we believe others perceive us.Cooley, C. H. (1922). Human nature and the social order. New York: Scribner. Writing at about the same time as Cooley, George Herbert Mead likewise described how speech is the means by which each person develops a unique sense of self.Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. He reasoned that if each human lived alone then there would be no need for a “self.” The need arises from the fact that humans live in societies. Like Cooley, he conceptualized the self as having individual and social aspects; Mead called the individual element the “I”As first described by George Herbert Mead, the “I” is the individual aspect of your self and the “me” is the social aspect of your self. and the social element the “me.” The “I” is the spontaneous and creative self; the “me” is the looking-glass self (a term Mead borrowed from Cooley) a person constructs by imagining how a “generalized other” (a composite mental picture of society) perceives him or her. Acquiring and maintaining a “self” comes through negotiating it with others. In turn, negotiation is accomplished via language and talk—by communicating. Mead held that each person negotiates a sense of self by imagining what others think of him or her and then negotiating a self that will be accepted by others. A later theorist, Erving Goffman, built on Cooley’s and Mead’s theories by likening humans’ everyday relations to a drama; people are actors who each present a faceAccording to Erving Goffman, constructing your self is like a drama; that is, you are like an actor who presents a face to an audience and, as in a play, stages a life-story that you hope will gain social acceptance. and stage a (continually updated and amended) life story that will gain them social approval. The notion that the events of your life folded in a logical progression and can be told as a sequential narrative is really a conceit; events happen randomly so that, in fact, you must impose a “plot” upon them. And yet, just as in a play, your “audience” participates by suspending its disbelief in order to benefit from larger truths. So to play the game, save face with others and feel good about yourself, you must have coherent and satisfying life story to tell.Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Doubleday. If we extend these ideas to organizations, we can grasp how development of an organizational identity is a process of communicatively (and continually) negotiating (and adjusting) an organizational “self” by telling a coherent story that the organization’s members and publics will accept.

How people use communication to negotiate and manage their identities is a vital field of research of research in communication studies. William Cupach and Tadasu Imahori proposed an Identity Management Theory to explain the communication strategies that individuals use to manage their identities, or “support” their “faces,” at various stages of their interpersonal relationships.Cupach, W. R., & Imahori, T. T. (1993). Identity management theory: Communication competition in intercultural episodes and relationships. In R. L. Wiseman & J. Koester (Eds.), Intercultural communication competence (pp. 112–131). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. The impact of group affinities (family, gender, ethnic, cultural) and intergroup encounters on identity is explored by Stella Ting-Toomey’s Identity Negotiation Theory.Ting-Toomey, S. (1993). Communication resourcefulness: An identity negotiation perspective. In R. L. Wiseman & J. Koester (Eds.), Intercultural communication competence (pgs. 72–111). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. (2005) etc Michael Hecht and his colleagues look at identity as a layered phenomenon that has individual, social, and communal properties which are enacted via communication.Hecht, M. L., Warren, J. R., Jung, E., & Krieger, J. L. (2005). The communication theory of identity: Development, theoretical perspective, and future directions. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Theorizing about intercultural communication (pgs. 257–278). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Interest in exploring the formation of individual and group identities through communication arose in the 1980s and has remained strong. Not surprisingly, this movement also stimulated scholarly interest in theorizing the dynamics of organizational identity.

The Concept of Organizational Identity

Through the biological metaphor we grasped how an organization must establish boundaries, even if permeable and blurred, in order for the notion of an “organization” to have any meaning. And through likening the organization to a person, we saw how these boundaries must be communicatively negotiated in ways that distinguish the organization’s story from those of other organizations in a socially acceptable manner. We chose this way of introducing our topic because, as Dennis Gioia observed, the “important features of individual identity supply the basis for the extension of the notion to organizations.”Gioia, D., op cit., pg. 20. Blake Ashforth and Fred Mael similarly noted that identity has been researched at the level of the individual, group and, more recently, the organization because of the many parallels across the three levels.”Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1996). Organizational identity and strategy as a context for the individual. Advances in Strategic Management, 13, 19–64.

So we turn now to the literature on organizational identityIn Stuart Albert and David Whetten’s original conception, organizational identity has three dimensions as its reflects the central character of an organization and its own claims of distinctiveness, and as it endures over time; subsequent scholars have explored how organizational identity can change and how an organization can have multiple identities., a concept that originated in 1985 with Stuart Albert and David Whetten. They defined organizational identity as a tripartite combination of “the central character of an organization” (e.g., its values, practices, services, products, structure, ownership), the distinctive qualities that it claims to possess, and the enduring manifestation of its identity over time.Albert, S. A, & Whetten, D. A. (1985). Organizational identity. Research in Organizational Behavior, 7, 263–295; pg. 292. According to this definition, then, the fast food chains described in the opening scenario of this chapter have formed identities that bring together their central characters as retail restaurants operated through a franchise business model, their individual claims to distinction vis-à-vis the other chains, and their consistency in sticking with their respective identities. Albert and Whetten did not suggest leaders “decide” the identities of their organizations. Rather, identity formation is an interactive process in which outsiders voice perceptions of an organization, so that the organization’s definition of itself is influenced as it considers this feedback and reflects on how it fits into its environment.Ibid, pg. 273.

Their conception was modeled on the processes of individual identity formation theorized by Cooley, Mead, and Goffman. Writing a few years later, Ashforth and Mael further grounded organizational identity in social identity theoryProposed by Henri Tajfel and John Turner, social identity theory (SIT) holds that one’s self-concept combines a “personal identity” based on individual traits with a “social identity” based on group classifications. (SIT).Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14, 20–39; pg. 21 This psychological theory, proposed in the 1970s by Henri Tajfel and John Turner, holds that one’s self-concept combines a “personal identity” based on individual traits with a “social identity” based on group classifications.Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 38–43). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole. At the time, most social psychologists believed a group identity was generated through competition with other groups; Tajfael and Turner contended that a group identity can emerge when members feel like insiders. SIT thus provided an insight that, through Ashford and Mael’s application, aided in further developing the concept of organizational identity. As David Seidl noted, SIT explained how “the individual member uses descriptions of the organization as part of his [sic] own self-descriptions” and thereby opened the door “to apply psychological identity theories to organizations.”Seidl, D., op cit., pg. 72.

Since the work of Albert and Whetten and Ashford and Mael in the 1980s, the literature on organizational identity has continued to expand. Over three decades, the concept has moved from Albert and Whetten’s original thesis—that organizational identity is central, distinctive, and enduring—to a more nuanced view: identity is adaptive, even unstable, and exists in dynamic relation with external audiences’ and internal members’ perceptions of an organization. In particular, researchers question whether identity can be seen as enduring when today’s organizations exist in a world of accelerating change and many are now set up as loosely structured networks. Recently, Mary Jo Hatch and Majken SchultzHatch, M. J., & Schultze, M. (2004). Organizational identity: A reader. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. summarized the major developments in theorizing organizational identity, which are presented in Table 8.2 "Theoretical Developments: Hatch & Schultz" below.

Table 8.2 Theoretical Developments: Hatch & Schultz

| ROOTS IN SOCIOLOGY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY | ||

| CooleyCooley, C. H., op cit. | 1902 | The self has both individual and social aspects. The social aspect is constructed as a “looking-glass self” when a person considers how others may perceive him or her. |

| MeadMead, op. cit. | 1934 | The self is comprised of an “I” (the spontaneous and creative aspects of self) and a “me” (the looking-glass self that imagines how it is perceived by the “generalized others”). |

| GoffmanGoffman, op cit. | 1959 | The self is a “face” that each person “presents” to others. Negotiating and maintaining the self is like a drama; a person strives to present a face that will be accepted by an audience of others. |

| Tajfel & TurnerTajfel & Turner, op cit. | 1979 | One’s self-concept combines a personal identity based on individual traits with a social identity based on group classifications. Group identities can emerge as members feel like insiders. |

| Brewer & GardnerBrewer, M. B., & Gardner, W. (1996). Who is this “we”? Levels of collective identity and self representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 83–93. | 1996 | The self can be analyzed at three levels: personal self-concept, relational self-concept, and collective self-concept. |

| EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONCEPT | ||

| Albert & WhettenAlbert & Whetten, op cit. | 1985 | Originated concept of organizational identity, theorized as a combination of an organization’s central character, the distinctive qualities it claims to possess, and the enduring manifestation of an identity over time. |

| SchwartzSchwartz, H. S. (1987). Anti-social actions of committed organizational participants: An existential psychoanalytic perspective. Organization Studies, 8, 327–340. | 1987 | Proposed that research on organizational identity can be pursued through a psychoanalytic framework. |

| Ashforth & MaelAshforth & Mael, Social identity theory, op cit. | 1989 | Applied Tajfel and Turner’s social identity theory to organization studies and introduced the concept of “organizational identification” to describe how individual members identify with an organization. |

| AlvessonAlvesson, M. (1990). Organization: From substance to image? Organization Studies, 11, 373–394. | 1990 | Introduced the concept of “organizational image” as an aspect of organizational identity. |

| Dutton & DukerichDutton, J. E., & Dukerich, J. M. (1991). Keeping an eye on the mirror: Image and identity in organizational adaptation. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 517–514. | 1991 | Investigated how organizational identities adapt in response to an organization’s environment and concerns for how it is perceived. |

| Ginzel, Kramer & SuttonGinzel, L. E., Kramer, R. M., & Sutton, R. I. (1993). Organizational impression management as a reciprocal influence process: The neglected role of the organizational audience. Research in Organizational Behavior, 15, 227–266. | 1993 | Adapted Goffman’s notion of impression management to organizations, thus envisioning impression management not as merely a managerial function but as a negotiation between an organization and its audiences. |

| RECENT DEVELOPMENTS: MULTIPLE IDENTITIES | ||

| Pratt & RafaeliPratt, M. G., & Rafaeli, A. (1997). Organizational dress as a symbol of multilayered social identities. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 862–898. | 1997 | Organization members manage multiple identities; for example, their identities as members of a specific organization and their identities as members of their professional community. |

| Golden-Biddle & RaoGolden-Biddle, K., & Rao, H. (1997). Breaches in the Boardroom: Organizational identity and conflicts of commitment in a nonprofit organization. Organization Science, 8, 593–611. | 1997 | Different segments of an organization may have different identities, which may lead to “hybrid identities” as members combine different (and sometimes conflicting) identities. |

| RECENT DEVELOPMENTS: STABILITY AND CHANGE | ||

| Gioia, Schultz & CorleyGioia, D. A., Schultze, M., & Corley, K. G. (2000). Organizational identity, image, and adaptive instability. Academy of Management Review, 25, 63–81. | 2000 | Contrary to Albert and Whetten’s description of organizational identity as enduring, identity is dynamically unstable and adaptive. The label given to an organization may be stable, but the meaning of the label changes. |

| Hatch & SchultzHatch, M. J., & Schultz, M. (2002). The dynamics of organizational identity. Human Relations, 55, 989–1018. | 2002 | Organizational identity is formed, maintained, and transformed through the dynamic interaction of organizational identity, organizational image, and organizational culture. |

| RECENT DEVELOPMENTS: NARRATIVE AND DISCOURSE | ||

| Czarniawska-JoergesCzarniuawska-Joerges, B. (1997). Narratives of individual and organizational identities. Communication Yearbook, 17, 193–221. | 1997 | Organizational identity may be analyzed as a narrative production or a story that an organization tells to gain acceptance. |

| Alvesson & WillmottAlvesson, M., & Willmott, H. (2002). Identity regulation as organizational control producing the appropriate individual. Journal of Management Studies, 39, 619–644. | 2002 | Managerial interests attempt to regulate organizational identity in order to “produce” an “appropriate” member and thus maintain control. |

| RECENT DEVELOPMENTS: AUDIENCES | ||

| Elsbach & KramerElsbach, K. D., & Kramer, R. M. (1996). Members’ response to organizational identity threats: Encountering and countering the Business Week rankings. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 442–476. | 1996 | Threats to organizational identity (e.g., criticism in the media) prompt members to respond with various strategies to affirm and repair the threatened identity and thus restore their own social identities. |

| Cheney & ChristensenCheney & Christensen, op. cit. | 2001 | An organization’s internal and external communication is linked through its identity. How an organization sees itself and believes others see it will affect corporate issue management. |

To get a sense of where the theory of organizational identity is headed, consider how fast food chains have been transformed over the years. In the 1960s and 70s when families seldom ate out, McDonald’s advertising proclaimed “You Deserve a Break Today.” Back then its main rival, Burger King, trumpeted the slogan “Special Orders Don’t Upset Us” to reassure moms that their finicky kids would not balk at going out to dinner. Television commercials for Kentucky Fried Chicken were aimed at mothers who could enjoy an occasional respite from the stove by putting a ready-made, home-style meal on the family dinner table. Today, of course, families eat out regularly and fast fare, rather than home cooking, sets consumer taste preferences. As their environment has changed, the chains have adapted their identities—and are adapting again, even now, in response to concerns about “McDonaldization” and obesity. With people spending more time and eating more meals in fast food establishments, all of the major chains are cultivating identities akin to comfortable sit-down restaurants with quality menus.

A further challenge for research on organizational identity is a problem that has confronted those who study organizational culture. As we learned in Chapter 6 "Organizational Communication Climate, Culture, and Globalization", the idea of organizational culture was popularized in the 1980s by the business press and, at the same time, separate literatures developed in management science (taking the view that an organization “has” a culture which can be managed) and organization studies (taking the view that an organization “is” a culture). A similar situation exists in the expanding literature on organizational identity. The business press has offered popularized notions of organizational (or corporate) identity (or image); the management science literature has explored how organization leaders can form, maintain, and transform identity; and the organization studies literature—as seen in Table 8.2 "Theoretical Developments: Hatch & Schultz" above—has investigated identity as a phenomenon that emerges through social interaction. Through it all, terms such as organizational identity, corporate identity, organizational image, corporate image, organizational culture, and corporate culture have assumed different meanings to different scholars and researchers.

Hatch and Schultz attempted to sort out and synthesize these literatures with a theory that not only distinguishes the differences between identity, image and culture, but shows how each dynamically impacts on the other. Along the way, they put forth a theory of how organizational identity is formed, maintained, and transformed.

Identity, Image, Culture

While the term organizational identity is common in the literature of organization studies, Hatch and Schultz found that the term corporate identity appears frequently in the literature on managerial strategy and marketing. Upon review, they discovered that the term “organizational identity” typically connoted something that was transmitted internally via interpersonal communication and was shared by all organization members. In contrast, “corporate identity” often connoted a managerial perspective that was transmitted to external stakeholders via mediated communication. But “instead of choosing between corporate and organizational identity” as a preferred term, Hatch and Schultz “advocate combining the understandings . . . into a single concept of identity defined at the defined at the organizational level of analysis.”Hatch, M. J., & Schultz, M. (2000). Scaling the Tower of Babel: Relational differences between identity, image, and culture in organizations. In M. Schultz, M. J. Hatch & M. H. Larsen (Eds.), The expressive organization: Linking identity, reputation, and the corporate brand (pp. 13–35). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; pg. 17. Their proposal is grounded in the notion, described at the outset of this chapter, of organizational identity as a dialectic phenomenon in which internal sense-making about “who we are” interacts dynamically with the perceptions of external stakeholders.

To construct a concept of organizational identity that unifies its internal and external aspects, Hatch and Schultz’s began by defining what identity is not. They observed in the organizational literature that identity and image were often linked, as were identity and culture. But is identity synonymous with image? Or is it synonymous with culture? And if not, what are the differences? To spell them out Hatch and Schultz delineated, as illustrated in Table 8.3 "Identity, Image, and Culture: Hatch & Schultz" below, how the concepts might be distinguished.

Table 8.3 Identity, Image, and Culture: Hatch & Schultz

| Distinguishing Culture and Identity | Distinguishing Identity and Image | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CULTURE | IDENTITY | IDENTITY | IMAGE |

| Contextual | Textual | Internal | External |

| taken-for-granted assumptions and meanings that shape everyday organizational life | narrative of organization whose “text” its members “read” and shapes sense of “who we are” | perspective on the organization held by its own members | perspective on the organization held by its external stakeholders |

| Tacit | Explicit | Self | Other |

| taken-for-granted assumptions and meanings that do not require conscious reflection | reflections by members about the meaning of the organization which occur at a conscious level | perspective held by insiders who regard the organization as a “self” | perspective held by outsiders who regard the organization as an “other” |

| Emergent | Instrumental | Singularity | Multiplicity |

| members’ own local constructions of symbols out of organizational artifacts and meanings | use of organizational symbols and artifacts to express and communicate “who we are” | perspective of insiders who interpret the organization based primarily on the organization as a source | perspective of outsiders who interpret the organization based on multiple sources of information |

Organizational identityIn Stuart Albert and David Whetten’s original conception, organizational identity has three dimensions as its reflects the central character of an organization and its own claims of distinctiveness, and as it endures over time; subsequent scholars have explored how organizational identity can change and how an organization can have multiple identities., then, is according to Hatch and Shultz the internal perspective of members who identify with the organizational “self” as they “read” its narrative, base their interpretations on internal information, reflect consciously on its meaning, and deploy symbols and artifacts to express their collective identity. Organizational cultureTo distinguish organizational culture from organizational identity, Hatch and Schultz described culture as emerging from members’ symbolic constructions to form unconsciously accepted assumptions and meanings that shape everyday organizational life. Organizational image is the perspective held by external stakeholders who view the organization as “other” to themselves and interpret the organization based not only on the organization itself but on multiple sources. emerges from members’ symbolic constructions to form unconsciously accepted assumptions and meanings that shape everyday organizational life. Organizational imageTo distinguish organizational image from organizational identity, Hatch and Schultz defined image as a perspective held by external stakeholders who view the organization as “other” to themselves and interpret the organization based not only on the organization itself but on multiple sources. is the perspective held by external stakeholders who view the organization as “other” to themselves and interpret the organization based not only on the organization itself but on multiple sources.

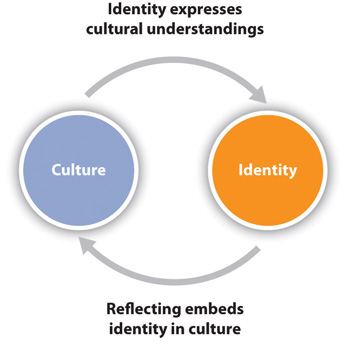

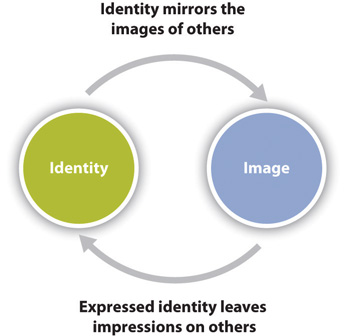

By these definitions, Hatch and Schultz mark out organizational identity, culture, and image as distinct phenomena. Nevertheless, these phenomena do not operate in isolation but exist in dynamic relationships by which identity and culture, and identity and image, influence one another. Their Organizational Identity Dynamics Model holds that identity and culture are related as conscious “reflecting embeds identity in culture” and “identity expresses cultural understandings,” and that identity and image are related as “expressed identity leavers impressions on others and “identity mirrors the images of others.”Hatch & Schultz, The dynamics of organizational identity, op cit.; pg. 379. In other words, as members consciously reflect on an organization’s identity, their shared understandings become internalized and part of a tacit culture whose taken-for-granted assumptions are manifested through the symbols and artifacts that members construct to express “who we are.” And as those expressions of “who we are” leave impressions on outsiders to create the organization’s external image, the image becomes the organization’s own looking-glass self by which the organization consider how it is generally perceived and accordingly adjusts and (re)negotiates its identity. Hatch and Schultz graphically represented the identity/culture and identity/image dyads as shown in Figure 8.1 "Organizational Identity and Culture: Hatch & Schultz" and Figure 8.2 "Organizational Identity and Image: Hatch & Schultz" below.

Figure 8.1 Organizational Identity and Culture: Hatch & Schultz

Figure 8.2 Organizational Identity and Image: Hatch & Schultz

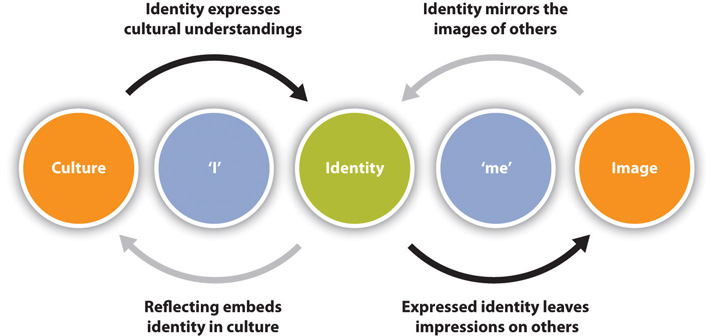

Taking their cue from Mead, Hatch and Schultz labeled the identity/culture dyad as the organizational analog for the “I” of the organizational self, and the identity/image dyad as the analog of the “me.” Thus, through the dynamic interrelationship between organizational identity and culture, members construct an organizational “I” that is tacit internalized, and furnishes the context for making meaning. And through the dynamic interrelationship between identity and image, members construct an organizational “me” that must be continually negotiated with others. Yet Mead’s original theory also held that the “I” and the “me” shaped one another. Hatch and Schultz’s Organizational Identity Dynamics Model therefore combines the two dyads and puts identity as the nexus between the organizational “I” and “me,” as shown in Figure 8.3 "Organizational Identity Dynamics Model" below.

Figure 8.3 Organizational Identity Dynamics Model

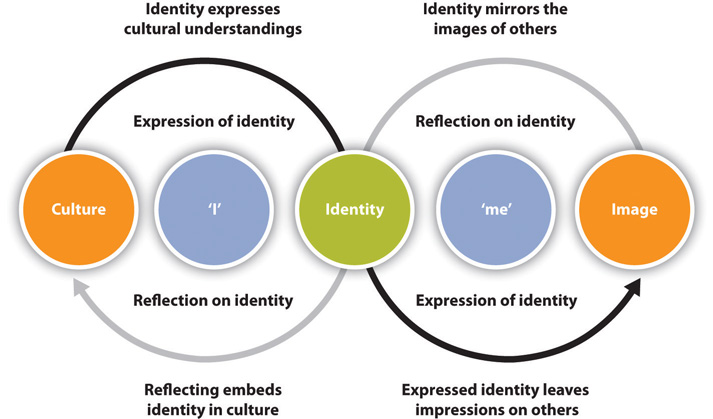

By extending Hatch and Schultz’s Organizational Identity Dynamics Model, as depicted in Figure 8.4 "Integration of Culture and Image via Identity", we can see how identity mediates—provides a transmission belt, if you will—between internal culture and external image. The figure below shows how organizational culture and image are integrated through the two processes of reflection on identity and expression of identity.

Figure 8.4 Integration of Culture and Image via Identity

Identity as a Mutable Quality

Conscious reflection on organizational identity is a key to the notion of adaptive instabilityChallenging Albert and Whetten’s thesis that organizational identity is enduring, Dennis Gioia and his colleagues argued that identity has the quality of adaptive instability as external feedback and events trigger challenges to an organization’s image and the organization responds by reflecting on how it sees itself and how others see it. advanced by Gioia, Schultz, and Corley.Gioia et al., Organizational identity, image, and adaptive instability, op cit. Their theory addresses a trend that was recognized by Stuart Albert, who originated the concept of organization a generation earlier. In the twenty-first century, organizations operate in a world characterized by the “flattening of hierarchies, the growth in teamwork and empowerment, the outsourcing of secondary competencies, and so on [that] are means of creating flexible pools of sophisticated capacities.”Albert, S., Ashforth, B. E., & Dutton, J. E. (2000). Organizational identity and identification: Charting new waters and building new bridges. Academy of Management Review, 25, 13–17; pg. 13. In such a world, can organizational identity be an enduring trait? Albert and his colleagues argued that the dismantling of bureaucratic structures increases the need for cognitive structures—that is, identities—which give organizations a rudder to steer by. But Gioia, Schultz, and Corley challenged the notion that organizational identity is enduring—which, together with centrality and distinctiveness, is one of the three dimensions contained in Albert and Whetten’s original definition.

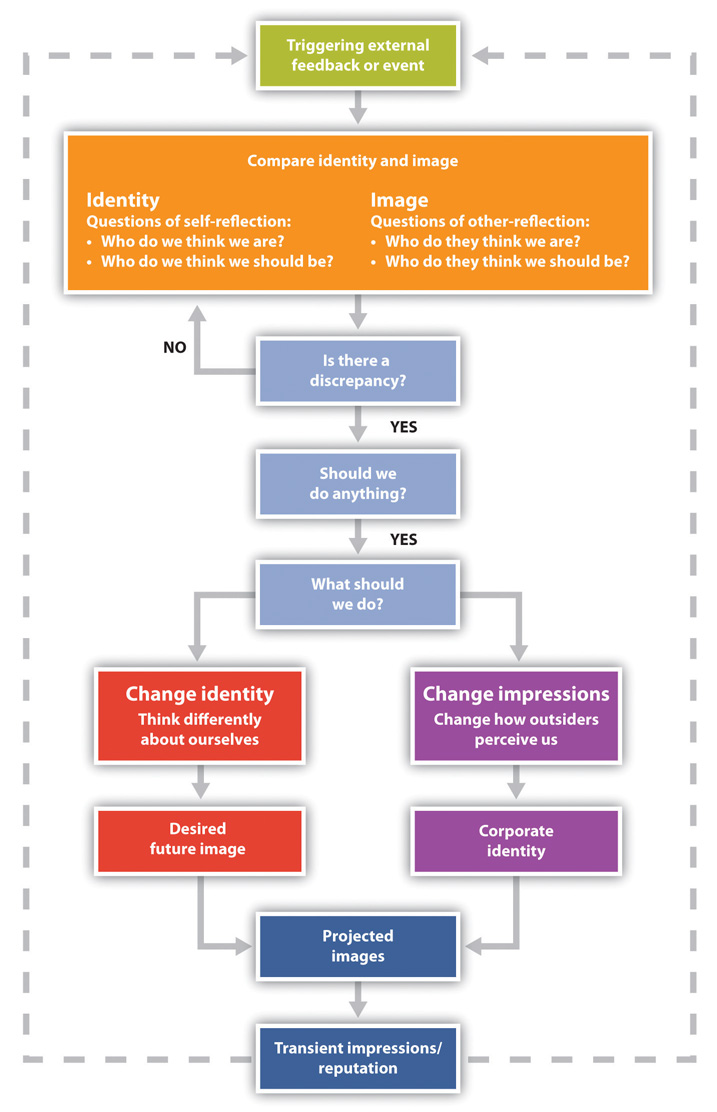

In their model—as in the Organizational Identity Dynamics Model described earlier—identity and image are distinct but interdependent phenomena. As the external impressions that form an organization’s reputation are inevitably subjected to feedback and events, members ask themselves four questions. Two are questions of self-reflection: Who do we think we are? Who do we think we should be? Two are questions of other-reflection: Who do “they” think we are? Who do “they” think we should be? If a discrepancy is detected between self-perception and other-perception, and if action is believed to be warranted, then organization members must ask: How should we change our identity (the way we think about ourselves) to sustain a new image? And how should we change our image (the way outsiders perceive us) to sustain a new corporate identity? The changes are projected to outsiders, external impressions of the organization are altered, and the adaptive process—shown in Figure 8.5 below—reboots (and continually recurs) all over again. As such, argued Gioia, Schultz and Corley, organizational identity is best seen as unstable and mutable rather than enduring.

Figure 8.5

Identity-Image Interdependence: Gioia et al.

Communicating Organizational Identity

Organizational identity is projected to external audiences through various means of communication—a topic we will explore at length in Chapter 14 "Stress, Conflict, and Negotiation". Taken together, these are often called “strategic communication” or “integrated marketing communication.” Separately, scholars and practitioners designate these means of communication as advertising, marketing, and public relations. As David Guth and Charles Marsh explain:

- Advertising is “the use of controlled media (media in which one pays for the privilege of dictating message content, placement, and frequency) in an attempt to influence the actions of targeted publics.”

- Marketing is “the process of researching, creating, refining, and promoting a product or service to targeted consumers.”

- Public relations is “the management of relationships between an organization and its publics.”Guth, D. W., & Marsh, C. (2012). Public relations: A value-driven approach (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon; pg. 11.

If you are majoring in communication then you may be concentrating on advertising, marketing, and public relations; you may aspire to do these activities as a career. Certainly, many communication majors end up as advertising, marketing, or public relations professionals. Traditionally, these activities are treated as linear communication (see Chapter 4 "Modern Theories of Organizational Communication") in which a sender conveys a message through a channel to a receiver. Theories of mass communication have progressed over the past eighty years from the simplistic “magic bullet theory” (mass media direct sway the public) and two-step theory (mass media reach opinion leaders, who sway the public), to the n-step theory (mass media reach the different opinion leaders on various issues, who sway the public on those issues) and diffusion theory (mass media influence people who then influence their peers), and to agenda-setting theory (mass media do not determine what people think but, rather, what they think about)McCombs, M. & Shaw, D. (1972). The agenda-setting function of the mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36, 176–187. and uses and gratifications they (people are not passive users of media but choose their information sources).Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1973/1974). Uses and gratifications research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 37, 509–523. The latter theory envisions mass communication as a two-way process in which media users’ choices influence media producers, even as media producers’ messages influence users who choose to consumer their programming. Similarly, public relations theory views “PR” not as one-way and asymmetrical, but as a two-way symmetrical process by which an organization and its stakeholders mutually resolve conflicts.Hunt, J. E., & Grunig, L. A. (1992). Models of public relations and communication. In J. E. Grunig (Ed.), Excellence in public relations and communication management (pp. 285–326). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

With this growing appreciation for the two-way nature of external organizational communication, George Cheney and Lars Christensen have injected the concept of organizational identity into the mix. Corporate communication campaigns are generally viewed as linear or interactional: organizational leaders think up a message, strategically choose the channels that most effectively reach the desired recipients, and measure results to determine success and guide future campaigns. In other words, corporate communications are formulated according to the rational intentions of corporate communicators. But Cheney and Christensen challenged this assumption: “[I]nternal perceptions (identities, expectations, and strategies) strongly affect what problems are ‘seen,’ what potential solutions are envisioned, and how the problems are ultimately addressed.” Thus, “organizational identity affects the diagnosis of issues” and how corporate leaders manage them.Cheney & Christensen, op cit., pg. 249. This leads Cheney and Christensen to observe that, if organizational identity is the reference point for corporate communicators, then corporate communication and issue management are self-referential and, even though they “seem to be directed toward others, [they] may actually be auto-communicativeAs George Cheney and Lars Christensen noted, an organization’s identity shapes how its leaders and managers diagnose and address problems; thus, since corporate issue management is self-referential, corporate communication (advertising, marketing, public relations) that seems directed to external audiences may actually be auto-communication as the organization in reality talks primarily to itself., that is, directed primarily toward the [organizational] self.”Ibid, pg. 258.

This startling observation has profound meaning for anyone who is, or aspires to be, a corporate communicator. Cheney and Christensen laid out a number of ethical concerns. For example, as a corporate communicator you may need to ask yourself whether your organization’s culture is disposed toward actions of integrity or of harm. You may need to question whether you are conveying “truth” when, because your point of reference is a given organizational identity, your messages emerge from your own perspective. At worst, your messages may have become so auto-communicative, and thus your system so closed, that you are only talking to yourself. The antidote to self-referentiality, argue Cheney and Christensen, is self-reflexivity. “To know the environment better, organizations should, in other words, try to know themselves.” Only by bringing core meanings and assumptions to the surface and by being “sensitive to . . . one’s own auto-communicative predispositions . . . can organizations hope to counter the self-referential tendencies” that can lead to unethical communications.Ibid, pgs. 263–264.

Key Takeaways

- Different ontologies about organizations (i.e., the nature of their being) lead to different perspectives on organizational identity. A functionalist (or postpositive) ontology regards identity as one of a set of attributes that an organization “has” and which therefore can be managed to optimize performance. An interpretive ontology regards identity as part of what an organization “is” since it emerges from the communicative interactions that constitute an organization. A critical ontology may see organizational identity as a tool of management to make its interests seem normal and natural. A postmodern ontology “de-centers” the very notion of identity by seeing organizations and individuals not as autonomous units but as sites of contestation between multiple discourses.

- In originating the concept of organizational identity, Stuart Albert and David Whetten built on theories of how individual identities are formed. They looked to the theories of Charles Horton Cooley, George Herbert Mead, and Erving Goffman who held that the “self” has both an individual and a social aspect. Extending these ideas to organizations, Albert and Whetten argued that organizational identity is the central character of an organization, the distinctive qualities it claims to possess, and the enduring manifestation of its identity over time. Formation of this identity, however, is an interactive process in which outsiders voice perceptions that influence the organization’s definition of itself. Since Albert and Whetten introduced their thesis in 1985, subsequent scholars have explored how organizations can have multiple identities and how organizational identities can change.

- To distinguish between organizational identity, organizational culture and organizational image, Mary Jo Hatch and Majken Schultz advanced a single theory to delineate each concept and explains how each phenomenon is interrelated with the other. Identity is a conscious perspective shared by members; culture emerges from members’ symbolic constructions to form tacit assumptions and meanings; and image is a perspective held by external stakeholders. Organizational identity and culture are interrelated because members’ reflections on identity become embedded in culture, even as identity comes to express cultural understandings. Organizational identity and image are interrelated because the expression of identity leaves impressions on outsiders, even as the organization takes those impressions into account in forming its identity. The identity/culture dynamic is the organizational equivalent to the individual aspect of the self, and the identity/image dynamic is equivalent to the social aspect.

- Dennis Gioia, Majken Schultz, and Kevin Corley challenged Albert and Whetten’s original assertion that organizational identity is enduring. Instead they argued that organizational identity is unstable and mutable. As external feedback and events trigger challenges to an organization’s image, its identity takes on the quality of “adaptive instability.” The organization reflects on itself, reflects on how it is perceived, compares its identity and its image, addresses any discrepancy by adjusting its identity to generate a desired image, projects the image to its external environment, and the process starts over again.

- An organization externally communicates its identity through advertising, marketing, and public relations. By these communications, organizations engage in corporate issue management. George Cheney and Lars Christensen pointed out that an organization’s identity—how it sees itself—shapes the problems it perceives and the solutions it formulates. When issue management becomes “self-referential” then corporate communication can actually become “auto-communication.” Though advertising, marketing, and marketing are purportedly directed to external audiences, the organization is really talking to itself. To avoid unethical communication, leaders and managers must be aware of their potential for auto-communication.

Exercises

- Think of an organization to which you have belonged. It might be a sports team on which you played, a club that you joined, a company where you worked, a church or mosque or synagogue where you have worshipped, or the college you now attend. What was (or is) its organizational identity? Now as you think of that identity, think of how it may have formed. How would you compare the formation of its identity to the way a person forms his or her identity? Are the theories of Cooley, Mead, and Goffman applicable to organizations? If so, how?

- Consider again the organization you named in Exercise 1. Describe how (using Albert and Whetten’s definition) its identity reflects its central character and the distinctive qualities it claims to possess, and how the identity has endured over time. Now, referring to Hatch and Schultz’s theory, describe how its identity, culture, and image are interrelated. Finally, referring to Gioia, Schultz and Corley’s theory of adaptive instability, describe how the organization’s identity has changed in response to external feedback and events that have challenged its image.

- Finally, think again of the organization you analyzed in Exercises 1 and 2. In what ways might its organizational identity—the way it sees itself—have shaped the problems it perceives and the solutions it formulates? Do you see, as Cheney and Christensen cautioned, any auto-communication in its advertising, marketing, and public relations? Explain your answer.

8.2 Identity and the Organization Member

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between organizational identity and identification.

- Recognize how management strives to guide employees’ socialization into the organization so employees strongly identify with the organization.

- Understand the processes by which organization members come to identify with the organization and incorporate that affinity into their self-identities.

- Grasp the postmodern and critical concern that managerial interests can use organizational identity and identification to sustain their control.

© Thinkstock

While organizational identity may be developed by an organization, organizational identification may be developed by its members. In introducing their concept of organizational identificationBlake Ashforth and Fred Mael started with social identity theory—which holds that one’s self-concept combines a “personal identity” based on individual traits with a “social identity” based on group classifications—and originated the concept of organizational identification by defining it as a specific form of social identification or perception of oneness with a group., Ashforth and Mael defined it as “a specific form of social identification,” where identification is “the perception of oneness with or belongingness to a group, involving direct or vicarious experience of its successes and failures.”Ashforth & Mael, Social identity theory, op cit., pgs. 22, 34. As noted above, you may have felt such identification with a sports team, a club, a house of worship, your alma mater, your place of work, or any number of organizations to which you have belonged. In a moment we will look at the psychological components that Asforth and Mael ascribed to organizational identification. But first, let us review the issue from the corporate side rather than the individual side.

From the Organizational Perspective

Leaders expend much effort toward managing employees’ identification with the organization in hopes of producing a workforce that is committed and loyal. So they pay much attention to ensuring new members “learn the ropes” and are socialized into the values and practices of the organization. As we review at length in Chapter 12 "Entering, Socializing, and Disengaging", Fredric JablinJablin, F. M. (1987). Organizational entry, assimilation, and exit. In F. M. Jablin, L. L. Putnam, K. H. Roberts, & L. W Porter (Eds.), Handbook of organizational communication: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 679–740). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.,Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 732–818). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. proposed that organizational socializationThrough processes initiated by management and through your own information gathering, you are socialized into the values and practices of an organization. occurs in three phases: anticipatory socializationAccording to Frederic Jablin’s framework, this is the first phase of organizational socialization in which, prior to formal entry, your environmental influences (e.g., family, media, peers, education, previous organizational experiences) and the employer’s recruiting process begins your socialization and aligns you with the organization’s identity., organizational entryThis second phase of organizational socialization spans the period from your initial employment offer, to your start on the job, to your full assimilation into the organization. and assimilation, and organizational disengagementDuring the third and final phase of organizational socialization you are separated from the organization; the manner of your disengagement is governed by the manner of your exit: whether by retirement, taking another job, or being discharged. and exit. These are illustrated in Figure 8.6 "Organizational Socialization" below.

Figure 8.6 Organizational Socialization

In the first phase, anticipatory socialization, you envision a specific job or career; this vision, according to Jablin, is likely influenced by family, media, peers, education, and any previous organizational experiences you have had. Along with environmental influences, noted Michael Kramer, the process of anticipatory socialization also takes in process of being recruited and hired by a specific organization.Kramer, M. W. (2010). Organizational socialization: Joining and leaving organizations. Malden, MA: Polity. Hiring, of course, leads to organizational entry and assimilation, the next phase of socialization. Jablin broke this phase down into three segments.Jablin, F. M. (2001). Organizational entry, assimilation, and disengagement/exit. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 732–818). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. During preentryDuring the preentry segment of organizational entry, when you have been offered a job but not yet begun, messages from your employer and the formation of initial impressions (on both sides) continue your organizational socialization. when you have been offered a job but not formally begun, you receive messages from the employer and initial impressions—both by and about you—are formed. Then during formal entryDuring the period of your initial formal entry into an organization, socialization continues as managers and coworkers help you “get on board” and as you try to make sense of how you fit in. the organization strives to acclimate you to its ways, while you try to make sense of how you fit in—until you experience the metamorphosisIn the last segment of the entry phase of organizational socialization, you experience the metamorphosis of full assimilation as an established member of the organization. of assimilation as an established member. Finally, the phase of organizational disengagement and exit occurs as you leave your employment. Through the first two phases in which you are recruited and hired, and then initiated and assimilated, organizations use many methods to “get you on board” and foster strong identification: new employee orientation programs, training programs, mentoring programs, information giving, and more.

From the perspective of organization leaders, the goal of the socialization is to produce employees who adopt—as we learned in Chapter 7 "Leader and Follower Behaviors & Perspectives"—a desirable followership styleThe concept of different leadership styles has prompted the complementary concept of different followership styles; the literature on management generally presupposes that strong organizational identification is a component of the followership style that effective managerial leadership should produce.. Ira Chaleff described the ideal follower as one how supports the leader and offers corrective feedback when needed.Chaleff, I. (2003). The courageous follower (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Barrett-Koehler. Roger Adair contrasted the Disgruntled follower and the Disengaged follower, with the excited and motivated Doer and the self-sacrificing Disciple.Adair, R. (2008). Developing great leaders, one follower at a time. In R. E. Riggio, I. Chaleff, & J. Lipman-Blumen (Eds.), The art of followership: How great followers create great leaders and organizations (pp. 137–153). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Robert Presthus divided followers into Upwardly Mobiles who revel in an organization’s system, Indifferents who go along, and Ambivalents who resist.Presthus, R. (1962). The organizational society: An analysis and a theory. New York, NY: Random House; pg. 15. Robert Kelley proposed a typology of Alienated, Passive, Conformist, and Exemplary followers—the latter combining active engaged in an organization with independent thought and judgment for achieving organizational goals.Kelley, R. (1992). The power of followership: How to create leaders that people want to follow and followers who lead themselves. New York: Doubleday/Currency. A common thread that runs through all of these typologies is the assumption that followers should identify strongly enough with an organization to perform their duties with motivation and commit their independent thought and judgment to the service and benefit of the group.

From an Individual Perspective

Fostering organizational identification is seen by leaders as an essential management function. But for individuals, the implications are more complex. As we noted at the outset of the chapter, people in modern societies derive much of their self-identities from the organizations with which they affiliate. Evaluating the implications must start with a better understanding of organizational identity as a psychological phenomenon. Since much of the research follows Ashforth and Mael’s construct of organizational identity, then that is where we will begin.Ashforth & Mael, Social identity theory, op cit.

Table 8.2 "Theoretical Developments: Hatch & Schultz" above illustrates how Ashforth and Mael applied to organizations the social identity theory of Tajfel and Turner—who, in turn, had built on the work of Cooley and Mead. Ashforth and Mael surveyed the extant literature and found that the term organizational identification was sometimes used interchangeably with such terms as commitment and internalization. Guided by social identity theory, they defined identificationAshforth and Mael defined identification as a cognitive construct (or mental picture of one’s self as intertwined with a group) as opposed to a set of behaviors or emotions; further, identification attaches the self to a social categories (“I am”), while internalization attaches the self to guiding principles (“I believe”). as a “cognitive construct that is not necessarily associated with any specific behaviors or affective states” since “an individual need only perceive him- or herself as psychologically intertwined with the fate of the group” and he or she “personally experienc[es] the successes and failures.”Ibid, pg. 21. In other words, your identification with a social group (such as an organization) is a mental picture rather than a set of actions or feelings. Further, identification can be distinguished from internalization: “Whereas identification refers to self in terms of social categories (I am), internalization refers to the incorporation of values, attitudes, and so forth within the self as guiding principles (I believe).”Ibid, pgs. 21–22. Table 8.4 "Distinguishing Organizational Identification" below puts these ideas into perspective by suggesting how an employee of the (hypothetical) Better Burgers franchise might express affinity with her organization.

Table 8.4 Distinguishing Organizational Identification

| Phenomenon | Example | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Identification | “I’m Better!” | The employee cognitively constructs a mental picture of her social self as intertwined with Better Burgers. |

| Behavior | “I’m loyal” | The employee takes the action of being committed to her association with Better Burgers |

| Emotion | “I’m love my job” | The employee enjoys feelings of satisfaction through her association with Better Burgers |

| Internalization | “I’m a burgerista” | The employee takes as her guiding principle the value that Better Burgers places on creativity and quality |

Ashforth and Mael argue that social identification can drive your actions and feelings, or vice versa. But when organizational identification is understood as a specific form of social identification—and when identification is seen as a cognitive construction or mental picture of the self, rather than a set of behaviors of feelings—then social identity theory suggests five factors can push employees and managers to identify with their organizations:

- The distinctiveness of the organization, so that membership confers a unique self-identity.

- The prestige of the organization, so that membership boosts self-esteem.

- An awareness of out-groups (i.e., other organizations), so that awareness of the in-group (i.e., one’s own organization) is reinforced.

- Competition with other organizations, so that distinctions are more clearly delineated.

- Groups formation factors that may include physical proximity, interpersonal relations, attractiveness, similarity, shared background, and common threats or aspirations.Ibid, pgs. 24–25.

Think again of the fast food chains we have used as an example throughout this chapter. If you were employed by one of these chains then (ideally, from management’s point of view) you might identify with the chain as your own self-identity becomes intertwined with its distinctiveness (“Our burgers are uniquely best!”) and prestige (“We’re the leading national chain!”) and with its contrasts to other chains (“The other chains want to be like us” and “The competitions won’t beat us because their burgers aren’t as good!”). In addition, your organizational identification might be enhanced if your restaurant is in your own neighborhood, if get along well with your manager and coworkers, and if your fellow employees are nice people who have similar personalities, background, dreams, and challenges.

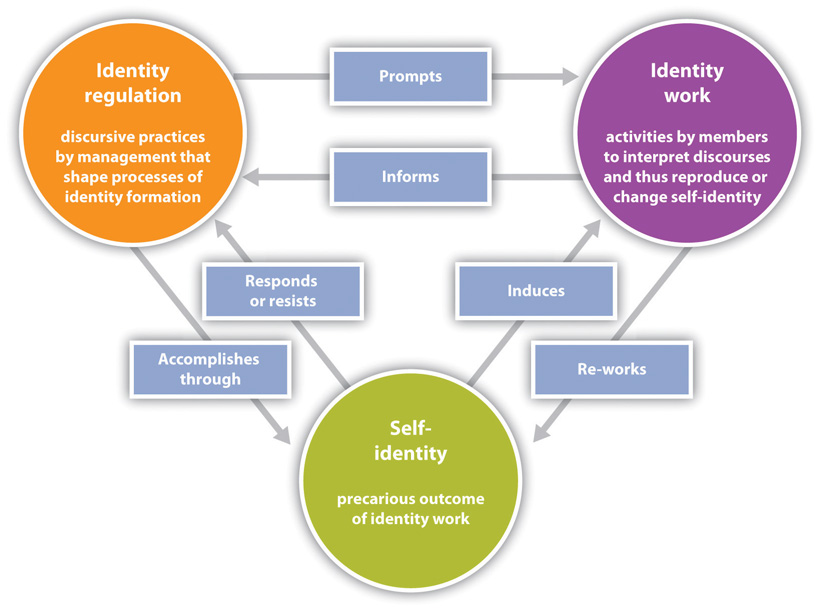

For your manager—and more broadly, for the fast food chain’s corporate leadership—a prime goal is to “produce” employees with the organizational identification described above. Of course, if you like where you work and feel a sense of belonging and purpose, then your organizational identification will tend to boost your job satisfaction. But it also follows that an organization’s attempts to “manage” your identity is tied to corporate leadership’s desire for control and predictability. Phillip Tompkins and George Cheney have called this concertive controlIn Tompkins and Cheney’s theory of organizational control, management gains concertive control when employees internalize approved attitudes and behaviors and discipline themselves.. Drawing on structuration theory (see Chapter 4 "Modern Theories of Organizational Communication"), they proposed that and identity-identification dualityUsing structuration theory as a framework, Phillip Tompkins and George Cheney argued that members’ identification with an organization’s identity furnishes a medium for members to act socially within the organization; in so doing, they reproduce the system so that member identification and organizational identity also become outcomes of their action—hence, an identity-identitfication duality. operates within organizations.Tompkins, P. K. & Cheney, G. (1985). Communication and unobtrusive control in contemporary organizations. In R. D. McPhee & P. K. Tompkins (Eds.), Organizational communication: Traditional themes and new directions (pp. 179–210). Newbury Park, CA: Sage; see also Scott, C. R., Corman, S. A., & Cheney, G. (1998). The development of a structurational theory of identification in the organization. Communication Theory, 8, 298–336. The more you are linked with other organization members that share the same premises, the more you will all cultivate like identities for yourselves and, in turn, be self-actualized by relationships with likeminded coworkers. Thus, identity and identification are both mediums and outcomes of social action. Tompkins and Cheney theorized that organizations deploy communication to control their members in five ways starting with simple controlIn Tompkins and Cheney’s theory of organizational control, the direct and open use of power by management is called simple control. through direct and open use of power, technical controlIn Tompkins and Cheney’s theory of organizational control, management’s selection of the communication tools employees are expected to employ is called technical control. that selects the communication tools members are expected to employ, and bureaucratic controlIn Tompkins and Cheney’s theory of organizational control, management’s determination of formal policies and procedures employees must follow is called bureaucratic control. that determines formal policies and procedures members must follow. Then through cultural controlIn Tompkins and Cheney’s theory of organizational control, management’s attempts to inculcate common values and practices around which members form their interests and relationships is called cultural control. organizations seek to inculcate common values and practices around which members form their interests and relationships, while through concertive control organizations induce members to discipline themselves as approved attitudes and behaviors come to seem natural and normal. As members accept these unwritten rules they in turn reinforce and reproduce them—individually and through interactions with other members—until these expectations become the very goals which motivate members and form their sense of obligation.

Tompkins and Cheney also drew on rhetorical theory (see Chapter 4 "Modern Theories of Organizational Communication"), citing Kenneth Burke’s concept of identification as a process in which consubstantiationRhetorical scholar Kenneth Burke (whom Tompkins and Cheney reference in their theory of organizational control) contended that persuasion cannot occur without identification; the basis for one person to persuade another is consubstantation or a sharing of substances that causes a listener to identify with a speaker., or a sharing of substances, causes persons to identify with one another and makes persuasion possible.Burke, K. (1969). A rhetoric of motives. Berkeley: University of California Press. Identification with an organization occurs as members imbibe its premises, shape their own identities by these premises, and ultimately reason by them. They likewise drew on Aristotle’s concept of the enthymemeAristotelian rhetorical theory (which Tompkins and Cheney reference in their theory of organizational control) holds that argument syllogistically from major premise, to minor premise, to conclusion; a skillful speaker who knows the mind of an audience can omit a well-known premise, which the audience mentally supplies and thus is drawn along to the speaker’s conclusion..Aristotle (2007). On rhetoric: A theory of civic discourse (2nd ed.) (G. A. Kennedy, Trans.). New York: Oxford University Press. Reasoning in organizations occurs syllogistically—often from a major premise, to a minor premise, to a conclusion. Enthymemic argument occurs when a premise is widely shared by an audience. A speaker merely omits that premise from the argument and thus impels the audience to fill in the missing premise and be drawn along to the speaker’s conclusion. So for example, when management and workers share the premise that profits are good for everyone, managers need only urge employees to practice “customer service excellence” and employees will supply the missing premise that “satisfied customers are repeat customers” and so be drawn along to the conclusion that making a profit is an imperative. When such identification occurs, the organization has gained concertive control over its members.

From Postmodern and Critical Perspectives

Writing in the 1970s, French philosopher Michel Foucault described a fundamental change from premodern to modern societies. In the old era of kings, discipline was achieved through direct and physical punishments such as public beheadings of people who offended the order of the realm. In the present era of bureaucracies, however, discipline is achieved not through direct and physical means but through indirect and intangible means, such that people come to discipline themselves. Foucault gave the analogy of a state prison, which is an invention of modern society. Inmates are aware of the faceless, all-seeing (or “panoptic”) guard tower above them. Knowing they are not watched every moment but could be at any moment, they discipline themselves.Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). New York: Vintage. (Original work published 1975) In a modern organization the method of surveillance may not be visual means such as cameras; bureaucracies have methods of reporting and accounting that keep tabs on people. Foucault became interested in the development of the concept of “self” throughout Western history and concluded that the “self” has become one of four “technologies” that operate in the modern world. These include:

(1) technologies of productionFour “technologies” or modes for getting things done, theorized Michel Foucault, operate in the modern world; technologies of production permit us to manipulate the physical world., which permit us to produce, transform, or manipulate things; (2) technologies of sign systemsFour “technologies” or modes for getting things done, theorized Michel Foucault, operate in the modern world; technologies of sign systems permit us to communicate., which permits us to use signs, meanings, symbols, symbols, or signification; (3) technologies of powerFour “technologies” or modes for getting things done, theorized Michel Foucault, operate in the modern world; technologies of power submit individuals to domination and determine their conduct., which, which determine the conduct of individuals and submit them to certain ends or domination, an objectivizing of the subject; (4) technologies of the selfFour “technologies” or modes for getting things done, theorized Michel Foucault, operate in the modern world; technologies of the self permit individuals to modify their bodies, thoughts, conduct, and ways of being to attain desired ends., which permit individuals to effect by their own means or with the help of others a certain number of operations on their own bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and way of being, so as to transform themselves in order to attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection, or immortality. . . . each one of them is associated with a certain type of domination. Each implies certain modes of training and modification of individuals, not only in the obvious sense of acquiring certain skills but also in the sense of acquiring certain attitudes.Foucault, M. (1988). Technologies of the self. In L. H. Martin, H. Gutman & P. H. Hutton (Eds.), Technologies of the self: A seminar with Michel Foucault (pp. 16–49). Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press; pg. 18.