This is “Followership”, section 7.2 from the book An Introduction to Organizational Communication (v. 0.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

7.2 Followership

Learning Objectives

- Define the term followership.

- Explain Ira Chaleff’s styles of followership.

- Describe Roger Adair’s 4-D Followership Model.

- Differentiate among McCroskey and Richmond’s three Organizational Orientations.

In 1988, Robert Kelley wrote an article in the Harvard Business Review where he explained that so much of the research on what happens between organizational members is written from the perspective that leadership is king and everything else is periphery.Kelley, R. E. (1988). In praise of followers. Harvard Business Review, 66(6), 142-148. Instead, Kelley believed that followership should be center stage right along research and writing on leadership. Surprisingly, this article was met with a lot of controversy, “Some people just flat out didn’t like it, comparing followers to sled dogs whose destiny is always to look at the rear end of the dog in front of them, but never to see the wider horizon or make the decisions of the lead dog Other readers could not thank me enough for articulating what they secretly held in their hearts.”Kelley, R. E. (2008). Rethinking followership. In R. E. Riggio, I. Chaleff, & J. Lipman-Blumen (Eds.), The art of followership: How great followers create great leaders and organizations (pp. 5-15). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; pg 6. Since 1988, writings in the popular press and in academic circles have routinely discussed the nature of followership. While there is still some controversy over the nature of followership, leadership researchers uniformly now examine and discuss the importance of followership in the corporate environment.

So what then is followership? As a basic concept, followershipThe act or condition under which an individual helps or supports a leader in the accomplishment of organizational goals. is the act or condition under which an individual helps or supports a leader in the accomplishment of organizational goals. However, Jon Howell and Maria Mendez defined followership as less in terms of a straight-forward definition but more as different roles followership can take. First, followership can take an interactive role, which means that a follower’s role is to complement and support her or his leader in accomplishing organizational goals. Second, followership can be an independent role, where followers act independently of their leaders with little necessity for oversight or management. Lastly, followership can take on a shifting role perspective, where followership is seen as less a concrete title or position but rather a state one embodies depending on the tasks at hands. In some situations, an individual may be a leader and in others a follower depending on the context of the organizational goals. The rest of this section is going to examine a series of different perspectives in the literature involving organizational followership: Ira Chaleff’s styles of followership, Roger Adair’s 4-D Followership Model, and McCroskey and Richmond’s Organizational Orientations.

Ira Chaleff’s Styles of Followership

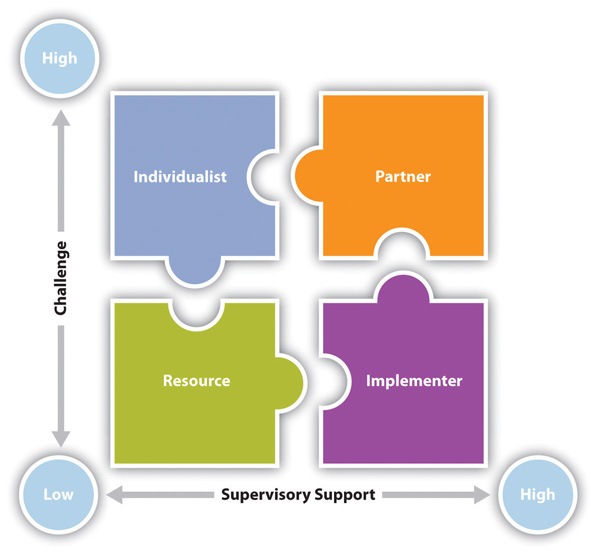

One of the first models for understanding the nature of leader-follower interactions from the follower’s perspective is Ira Chaleff’s Styles of Followership she discussed in her ground breaking book The Courageous Follower.Chaleff, I. (2003). The courageous follower (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Barrett-Koehler. Based on the name of the book, Chaleff’s perspective is that followership is an act of courage that someone decides to take. As such, she sees followership as having the courage to engage in two different behaviors: the courage to support the leader and the courage to challenge the leader’s behavior and/or policies. Figure 7.5 "Styles of Followership" demonstrates what happens when you combine the courage to challenge and support.

Figure 7.5 Styles of Followership

Resource

The first follower style discussed by Chaleff is the resourceFollower type described by Ira Chaleff who will not challenge nor support the leader doing only the minimal amount of work to keep her or his job.. The resource is someone who will not challenge nor support the leader. This follower basically does the minimal amount to keep her or his job, but nothing more.

Individualist

The second followership style is the individualistFollower type described by Ira Chaleff who will provide little to no support for her or his leader but has no problem challenging the leader’s behavior and policies.. This individual will provide little to no support for her or his leader, but has no problem challenging the leader’s behavior and policies. This individual is generally very argumentative and/or aggressive in her or his behavior. While this individual will often speak out when no one else will, people see this person as inherently contrarian so her or his ideas are generally marginalized.

Implementer

The third followership style is the implementerFollower type described by Ira Chaleff who will be more than happy to support her or his leader in any way possible, but the implementer will not challenge the leader’s behavior or policies even when the leader is making costly mistakes.. The implementer is more than happy to support her or his leader in any way possible, but the implementer will not challenge the leader’s behavior and/or policies even when the leader is making costly mistakes. The implementer simply sees it as her or his job to follow order, not question those orders. While this kind of pure-followership may be great in the military, it can be very harmful in the corporate world.

Partner

The final type of followership is the partnerFollower type described by Ira Chaleff who will support and challenge a leader because this follower sees her or himself as having a stake in the leader’s decisions.. Partner followership occurs when a follower is both supportive and challenging. This type of follower believes that he or she has a stake in a leader’s decisions, so he or she will act accordingly. If the partner thinks a leader’s decision is unwise, he or she will have no problem clearly dissenting within the organizational environment. At the same time, these followers will ultimately provide the most (and most informed) support possible to one’s leader.

Roger Adair’s 4-D Followership Model

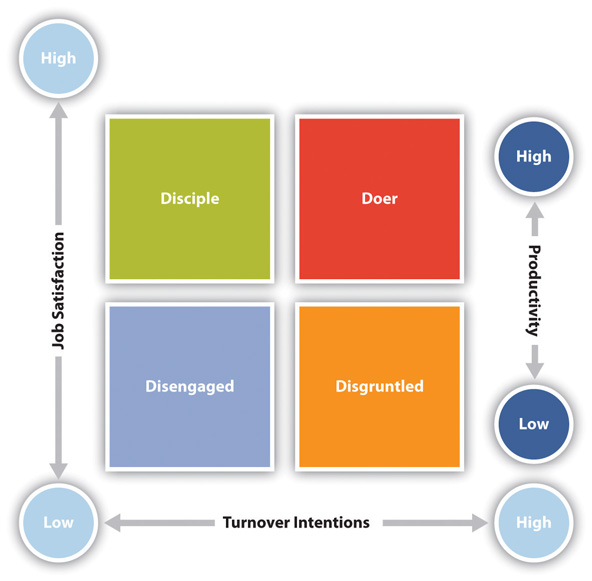

In 2008 Roger Adair proposed the 4-D Followership model to help explain the types of people who exist within an organization.Adair, R. (2008). Developing great leaders, one follower at a time. In R. E. Riggio, I. Chaleff, & J. Lipman-Blumen (Eds.), The art of followership: How great followers create great leaders and organizations (pp. 137-153). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. The basic model Adair proposed for understanding followers examines a follower’s level of job satisfaction and her or his productivity. Based on the combination of job satisfaction and productivity, Adair demonstrates the likelihood that someone will decide to leave the organization. The basic model can be seen in Figure 7.6 "4-D Followership Model".

Figure 7.6 4-D Followership Model

Disgruntled

The first type of follower is called the disgruntledType of follower described by Roger Adair who has encountered some event within the organization that has left them feeling detached, angry, or displeased, which leads to low levels of job satisfaction and productivity. follower. He or she has low levels of job satisfaction and is not overly productive at work either. These followers have typically encountered some event within the organization that has left them feeling detached, angry, or displeased. Maybe this person was passed up for a job promotion or he or she is being bullied in the workplace. Whatever the initial trigger, these individuals are toxic to the work environment. If the disgruntled follower is caught early on in her or his downward slip into this state, there is a chance to pull her or him away from the disgruntled cliff. Unfortunately, too many leaders do not notice the signs early on and these followers either end up reacting negatively in the workplace or they job ship as soon as they get an offer.

Disengaged

The second type of follower is someone who is disengagedType of follower described by Roger Adair doesn’t see the value in her or his work so he or she opts to do the minimum necessary to ensure her or his employment., or someone who doesn’t see the value in her or his work, so he or she opts to do the minimum necessary to ensure her or his employment. Often these individuals perceive their work as meaningless or not really helping the organization achieve its basic goals, so they basically tune out. Often people who are disengaged become so because the original expectations they had for the job are simply not met, so they may feel lied to by the organization, which can lead to low levels of organizational commitment.

Doer

The third type of follower is called the doerType of follower described by Roger Adair is highly motivated and constantly looking for bigger and better work opportunities either within their current organization or in a new one.. Doers “are motivated, excited to be part of the team. They are enterprising people, and overall are considered high producers. The only real issue with these employees is that no matter where they go in an organization, the grass always looks greener elsewhere.”Adair, R. (2008). Developing great leaders, one follower at a time. In R. E. Riggio, I. Chaleff, & J. Lipman-Blumen (Eds.), The art of followership: How great followers create great leaders and organizations (pp. 137-153). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; pg. 145. A doer often starts as someone who is upwardly mobile in the organization and become doers when one of two things occurs. First, doers want more out of life and if they don’t feel that there is continued possibilities for upward mobility within an organization, they are very likely to jump ship. Second, if a doer does not feel he or she is receiving adequate recognition for her or his contributions to the organization, then the doer will find someone who will give her or him that affirmation.

Disciple

The last type of follower is the discipleType of follower described by Roger Adair believs both in her or his work and in the overarching goal(s) of the organization, so this follower is highly satisfied and productive. and this individual is highly satisfied and highly productive. In an ideal world, only disciples would fall under leaders because they have no problem sacrificing their own personal lives for the betterment of the organization. These workers are true believers both in their work and in the overarching goal(s) of the organization. While some people may remain disciples for a lifetime, many more workers start as disciples and quickly become disengageds, disgruntleds, or doers. This generally happens because an organization’s own employees, processes, or systems do not encourage disciple behavior and eventually wear the disciple down to the point where their sunny organizational outlook becomes one filled with clouds.

James C. McCroskey and Virginia Richmond’s Organizational Orientations

In 1962, Robert Presthus created a theory of organizational life that defined three unique types of workers: upwardly mobiles, ambivalents, and indifferents. He defined these three terms thusly:

The upward-mobiles are those who react positively to the bureaucratic situation and succeed in it. The indifferents are the uncommitted majority who see their jobs as mere instruments to obtain off-work satisfactions. The ambivalents are a small, perpetually disturbed minority who can neither renounce their claims for status and power nor play the disciplined role that would enable them to cash in such claims [emphasis in original].Presthus, R. (1962). The organizational society: An analysis and a theory. New York, NY: Random House; pg. 15.

In 2004, James McCroskey and Virginia Richmond along with their students Aaron Johnson and Heather Smith created a measure to examine and test Presthus typology of workers to see whether the three organizational orientations held up to empirical scrutiny.McCroskey, J. C., Richmond, V. P., Johnson, A. D., & Smith, H. T. (2004). Organizational orientations theory and measurement: Development of measures and preliminary investigations. Communication Quarterly, 52, 1-14. Note 7.40 "Organizational Orientations—Short Form" contains a short version of the Organizational Orientations scale. Before continuing, please take a second to complete the measure.

Organizational Orientations—Short Form

Read the following questions and select the answer that corresponds with how you perceive your workplace. Do not be concerned if some of the items appear similar. Please use the scale below to rate the degree to which each statement applies to you:

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

- _____One of my goals in life is excelling at in my job.

- _____I would like to learn as much as possible in my job.

- _____Most of all, I really want to be recognized for the excellent work I do in the workplace.

- _____Accomplishing my organization’s goals is worth all the work you have to do.

- _____I am willing to work hard to accomplish my organization’s goals.

- _____Since I am a really good worker, I know I will succeed in my career.

- _____A job is a job, it doesn’t really matter where you work.

- _____I am generally indifferent to where I work.

- _____Generally, I just do as much as is required by my supervisor to get a paycheck.

- _____I don’t much care where I work, so long as I get a paycheck.

- _____One job is pretty much like any other.

- _____When it comes to choosing a workplace, I found the one that would let me get by doing the least amount of work.

- _____I really dislike the rules and regulations I am forced to live with at my job.

- _____Generally, I don’t like the rules that my workplace makes me follow.

- _____Most of the time, a halfhearted effort is all I feel I need to give at work.

- _____I really think my job should just give me a paycheck and leave me alone.

- _____One job is about like any other, a pain in the backside.

- _____What I want most in my job is to be left alone.

SCORING: To compute your scores follow the instructions below:

-

Upwardly Mobile

Scoring: Add scores for items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, & 6

For Upwardly Mobiles, scores should be between 6 and 30. If your score is above 15, you are considered an upwardly mobile worker. If your score is below 15, you’re not considered an upwardly mobile worker.

-

Indifferent

Scoring: Add scores for items 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, & 18

For Indifferents, scores should be between 6 and 30. If your score is above 15, you are considered a highly indifferent worker. If your score is below 15, you’re not considered an indifferent worker.

-

Ambivalent

Scoring: Add scores for items 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, & 12

For Ambivalents, scores should be between 6 and 30. If your score is above 15, you are considered an a highly ambivalent worker. If your score is below 15, you’re not considered an ambivalent worker.

Source: Wrench, J. S., Brogan, S. M., Fiore, A. M., & McKean, J. R. (2011, November). Consumerist education in America: When ideology impacts the basic purpose of higher education. Paper presented at the National Communication Association’s Convention, New Orleans, LA.

The Three Orientations

According to Virginia Richmond and James McCroskey, organizational orientations explain how followers orient themselves towards both their work and their workplace.Richmond, V. P., & McCroskey, J. C. (2009). Organizational orientations. In Organizational Communication for Survival: Making work, work (4th ed., pp. 82-93). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. To help us understand the organizational orientations and their relationship to followership, let’s examine each one separately.

Upwardly Mobiles

The upwardly mobileOrganizational orientation described by James C. McCroskey and Virginia Richmond associated with individuals who are devoted to their work, their organization, and the organization’s goals. organizational orientation is one associated with individuals who are devoted to their work, their organization, and the organization’s goals. To these individuals, working and their jobs are an inherent part of their lives. In fact, these people often identify their jobs as being careers and not just jobs. To upwardly mobiles, a jobPost of employment for an individual who is just looking to earn money. is a way to earn money, but a careerPost of employment for an individual who is pursuing lifelong ambitions and goals related to one’s chosen occupation. involves the pursuit of lifelong ambition and goals related to one’s chosen occupation. Upwardly mobile individuals see themselves as having careers and not just jobs. In fact, an inherent part of the identity of an upwardly mobile relates to her or his career (e.g., I’m a lawyer, I’m a teacher, I’m an accountant, etc…). These individuals generally are great followers because they really see their lives and their careers as highly intertwined constructs. However, upwardly mobile individuals want to continue up the hierarchy and will consider jumping ship if they do not see a place for them within an organization in the future.

Indifferents

The second way people orient themselves at work is the indifferentOrganizational orientation described by James C. McCroskey and Virginia Richmond describing followers who go to work and do their jobs in order to get a paycheck, these followers really sees life as something thatbegins once they leave the workplace organizational orientation. Where upwardly mobile see themselves as having careers, indifferents clearly believe they have a job. In essence, the indifferent follower is one who sees work as a means to an end. The indifferent goes to work, does her or his job in order to get a paycheck, but the indifferent really sees life as something that begins once he or she has left the workplace. Indifferent followers need more guidance because they will do the minimum amount of work necessary to keep their job and earn a paycheck. Indifferents will look for a new job if they believe their current job is starting to encroach on their life outside of work. As for their communicative behavior at work, their “communication on the job is about their family or personal life. When encouraged to communicate about organizational matters with colleagues, they generally say nothing, change the topic, or suggest that others should discuss these matters.”Richmond, V. P., & McCroskey, J. C. (2009). Organizational orientations. In Organizational Communication for Survival: Making work, work (4th ed., pp. 82-93). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; pg. 84.

Ambivalents

The last group of followers commonly seen in the workplace are ambivalents. AmbivalentsOrganizational orientation described by James C. McCroskey and Virginia Richmond that depicts a follower who is disgruntled by the existing hierarchical structure, the tasks they are assigned, and/or the organizational goals. are somewhat hard to describe because they can be unpredictable. Where upwardly mobiles like to work within the hierarchy to accomplish goals, indifferents go along with the hierarchy and do what they are told to do, ambivalents tend to like neither the existing hierarchical structure, the tasks they are assigned, nor the organizational goals. These individuals are just generally discontent. In fact, these individuals often think the grass would be greener in a different pasture. However, when they jump ship to a new organization, they tend to find themselves making the same complaints about their new organization as well. Furthermore, their moods and their behaviors within the organization can change on a daily basis. “These people can be supportive one day and destructive the next. They are moody, which makes it difficult for people to work with or for them.”Richmond, V. P., & McCroskey, J. C. (2009). Organizational orientations. In Organizational Communication for Survival: Making work, work (4th ed., pp. 82-93). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; pg. 85. Sadly, most organizational members and leaders learn to keep their distance of ambivalents and keep their interactions with ambivalents to “small talk” to avoid setting them off. Most organizations (and its members) will be happier and more productive when these individuals leave.

Outcomes of Organizational Orientations

In the original study by McCroskey, Richmond, Johnson, and Smith examining organizational orientations, the researchers set out to examine how the three orientations related to a series of different communication and organizational variables.McCroskey, J. C., Richmond, V. P., Johnson, A. D., & Smith, H. T. (2004). Organizational orientations theory and measurement: Development of measures and preliminary investigations. Communication Quarterly, 52, 1-14. First, they found that upwardly mobile individuals were more motivated and higher levels of job satisfaction, while indifferents and ambivalents were neither motivated nor satisfied. As for their communication with others, upwardly mobile individuals were shown to be considerably more communicatively competent than either indifferents and ambivalents. The third major finding from the first study examined how an individual’s organizational orientation impact her or his views of their supervisor’s credibility. Not surprisingly, upwardly mobile followers saw their leaders as credible (competent, caring, and trustworthy), while indifferent and ambivalent followers did not. These results were later confirmed in a second study that compared both nonprofit and for-profit organizational members.McCroskey, L., McCroskey, J.C., & Richmond, V. P. (2005). Applying organizational Orientations theory to employees of profit and non-profit organizations. Communication Quarterly, 53, 21-40.

In a 2008 study conducted by Alan Goodboy and James McCroskey, the researchers furthered our understanding of organizational orientations by examining the relationship between the three organizational orientations and nonverbal immediacy and Machiavellianism.Goodboy, A. K., & McCroskey, J. C. (2008). Toward a theoretical model of the role of organizational orientations and Machiavellianism on nonverbal immediacy behavior and job satisfaction. Human Communication, 3, 293-308. Nonverbal immediacy is the perceived psychological or physical closeness between two people. The nonverbal literature has consistently shown that nonverbal immediacy (which can be influenced by effective eye contact, appropriate use of gestures, smiling, etc.) is a positive communication trait that improves a variety of different communicative interactions including both leader-follower relationships and coworker relationships. In this study, upwardly mobile individuals were more likely to be nonverbally immediate in the workplace when compared to either indifferents or ambivalents. Machiavellianism, on the other hand, is a personality trait associated with an individual’s tendency towards manipulating those around them. Both indifferents and ambivalents were more likely to be highly Machiavellian in the workplace when compared to their upwardly mobile counterparts.

Overall, these three studies clearly show that understanding one’s follower’s organizational orientations can be very important for follower-leader interactions in the workplace. While leaders should cultivate upwardly mobile they shouldn’t ignore either indifferents or ambivalents in order to have a more productive and harmonious working environment.

Key Takeaways

- Followership is the act or condition under which an individual helps or supports a leader in the accomplishment of organizational goals. Followership is considered an act because of the various behaviors associated with following someone. Followership is conserved a condition because of an individual’s place within an organizational hierarchy.

- Ira Chaleff’s styles of followership is based on the degree to which an individual follower will support her or his leader and the extent to which a follower will challenge her or his leader. Based on these two characteristics, Chaleff proposes four distinct follower types: (1) resource (low challenge, low support), (2) individualist (high challenge, low support), (3) implementer (low challenge, high support), and (4) partner (high challenge, high support).

- Roger Adair’s 4-D Followership Model looks at the combination of worker’s level of job satisfaction and her or his intentions to leave the organization. Based on these two levels, Adair proposed four distinct types of workers: (1) disengage (low job satisfaction, low turnover intention), (2) disgruntled (low job satisfaction, high turnover intention), (3) doer (high job satisfaction, high turnover intention), and (4) disciple (high job satisfaction, low turnover intention). Ultimately, Adair also notes that disengaged and disgruntled followers are not very productive while doers and disciples are very productive followers.

- Based on Robert Presthus created a theory of organizational life, McCroskey and Richmond have operationalized and studied three unique Organizational Orientations: upwardly mobiles (individuals who see their careers as a vibrant part of their daily lives, so they strive to be their best at work), indifferents (followers who see work as a means to an end and really see life as something that happens outside the workplace), and ambivalents (individuals who are disgruntled with existing hierarchical structures, the tasks they are assigned, and/or the organizational goals.). Upwardly mobile followers are generally more motivated, productive, and satisfied when compared to their indifferent and ambivalent peers.

Exercises

- Thinking back to your most recent job, what type of follower would Ira Chaleff characterize you as? Why?

- Thinking back to your most recent job, what type of follower would Roger Adair characterize you as? Why?

- After completing the Organizational Orientations-Short Form scale in Note 7.40 "Organizational Orientations—Short Form", what organizational orientation is your most prominent? How do you think your organizational orientation affects your current job? Do you think your organizational orientation would change if you were in a job versus in a career?