This is “Strategies to Improve Listening in Groups”, section 7.4 from the book An Introduction to Group Communication (v. 0.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

7.4 Strategies to Improve Listening in Groups

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify physical actions which contribute to good listening.

- Identify effective pre-listening behaviors.

- Identify what to do and what to avoid doing when listening in a group.

The greatest compliment that was ever paid me was when one asked me what I thought, and attended to my answer.

Henry David Thoreau

Listening to people keeps them entertained.

Mason Cooley

First Things First

In the last few sections we’ve established that listening is a vital skill in groups. Now let’s review two fundamental points before we discuss specific steps for doing it well.

The first point is that before you can listen, you have to stop talking. This might seem self-evident, but in a culture like that of the United States, in which talking is highly valued, we may tend to overlook it.

The second point, though less obvious, is just as important. It is that both senders and receivers—both speakers and listeners—are responsible for effective listening. Listening actually transcends the mere reception of messages by listeners and imposes obligations on both senders and receivers in what Waldeck, Kearney, and PlaxWaldeck, J. H., Kearney, P., & Plax, T. (2013). Business & professional communication in a digital age. Boston: Wadsworth. called “sender-receiver reciprocityThe mutual obligation of speakers and listeners to create and understand meaning together..”

Senders should choose their messages according to the context or occasion. Furthermore, they should consider what media they will use to communicate them—for instance, face-to-face interaction or synchronous or asynchronous transmissions—and be mindful of the implications of their selection.

Image from http://www.public-domain-image.com

For their part, receivers must make an effort to listen, be prepared to provide feedback, and manage their responses to ensure relevance and civility. They should also practice what Beebe, Beebe, and IvyBeebe, S.A., Beebe, S.J., & Ivy, D.K. (2007). Communication: Principles for a lifetime (3rd ed.). Boston: Pearson. labeled “social decenteringThe act of stepping away from one’s own thoughts in order to try to experience the thoughts of others.”—i.e., “stepping away from your own thoughts and attempting to experience the thoughts of others.”

The Physical Side of Listening

As we’ve already pointed out, good listening is an active process. As such, it requires energy. In fact, listening is work—and not just mental work, either. To do the work of listening, which generally consumes the majority of your time whenever you interact with a group, you should be sure you’re physically primed and ready to go. To confirm that your body is really prepared for high-quality listening, you should first check your posture. Assuming that you’re seated, sit up straight and lean slightly forward. Not only does good posture allow you to remain relaxed and alert, but it makes it more likely that other people will see you as competent and confident.Burgoon, J.K., & Saine, T.J. (1978). The unspoken dialogue: An introduction to nonverbal communication. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Next, notice your breathing. Be sure you’re inhaling and exhaling deeply. Also, identify any aches or pains that may interfere with your ability to take in other people’s messages. See if you can shift into a position which will allow you to remain comfortable and attentive throughout the communication process.

Pre-listening

How much time and effort you put into getting ready to listen will depend among other things on what kind of group you’re in, how well you and the other members know each other, and what topics you’re dealing with. Sometimes you’re talking about light or superficial matters—like “Where shall we get together after we complete our project?”—and you can just dive into a conversation without any particular thought to getting ready to listen.

There will be occasions, however, when you ought to stop, consider, and plan your listening carefully. Let’s say you’re in a student government group considering requests for activity fee money, for instance, or a screening committee involved in hiring a new person to join your business. In cases like these, when careful, accurate listening will be at a premium, you should probably take some or all of these preparatory steps:

Assign listening tasks to people. Because social loafing is more likely when members aren’t held accountable for their behavior,Thompson, L. (2008). Organizational behavior today. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. you may want to ask individuals to listen for different kinds of information or divide a long period of listening into segments, each of which has a designated “major listener.”

Confirm (or reconfirm) your group’s norms with respect to listening. Remind yourselves about how you plan to take turns speaking.

Identify any potential contextual barriers to listening.Kelly, M.S. (2006). Communication @ work: Ethical, effective, and expressive communication in the workplace. Boston: Pearson. Such barriers may include the location in which you’re communicating, the cultural identity of group members, and the mixture of genders represented in the group.

Remind the members of the group that they should recognize their own biases, including their tendency to interpret information in the light of their beliefs.Hybels, S., & Weaver, R.L. (1998). Communicating effectively (5th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill. Perhaps note that each group members is tuned in to a special mental radio station, “WII-FMAn imaginary radio station whose call letters stand for “What’s in it for me?”,” which stands for “What’s in it for me?”

Decide whether it’s all right for group members to take notes or make audio recordings during the upcoming communication. If it is, decide whether you’d like to name one or more members “primary note-takers” or recorders.

Determine how often and when you plan to take breaks. Remember that “the mind can absorb only what the seat can endure.” Even though parts of a lengthy discussion may be engrossing, when the time for a scheduled break comes your listening ability will probably be rejuvenated if you pause at least long enough for people to stand and stretch for 30–60 seconds before proceeding.

Listening Itself

All right. Let’s say the members of your group have physically and mentally readied themselves to listen, and you’ve begun a discussion. What do you need to do as the process unfolds? Here are some important dos and don’ts:

In listening, do…

- Determine your purpose in listening, and keep it in mind. Thinking back to earlier in this chapter, are you listening to acquire information, to evaluate messages, to relax and enjoy ourselves, or to demonstrate empathy?

- Identify the levels at which group members are communicating their messages—e.g., emotional, political, or intellectual.

- Assess the relative significance of people’s comments and listen for main ideas rather than trying to take in everything on an equal plane. To help you do this, you may want from time to time to mentally summarize the message(s) you’re listening to.

- When possible and appropriate, urge other members of the group to speak, especially those who are less dominant. Say things like “Please go on”; “Tell me more”; “Care to expand on that?” Remember that each person has a unique perspective that can add to the group’s ability to consider ideas and make decisions.

- “Listen with your eyes.” Observe people’s body language and other nonverbal cues carefully, since those physical manifestations may add to or sometimes contradict their spoken words.

- Show interest in others’ messages through your own nonverbal actions. Establish and maintain eye contact. Smile. Adopt an open posture. Avoid fidgeting or slouching.

- Use “interactive questioningOpen-minded, open-ended questioning which serves to enhance mutual understanding among group members.”.Lumsden, G., & Lumsden, D. (2004). Communicating in groups and teams; Sharing leadership (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson. Ask open-minded and open-ended questions to clarify ideas & information; to probe a speaker’s reasoning and evidence; and to expand incomplete information. Use and ask for examples so that the speaker can connect your questions with his or her own world of experiences.

- Use tentative clarifying/confirming statements: e.g., “It sounds like…”; “You seem to think that…”; “As I get it, you…”

- Make polite, “targeted” interruptionsLumsden, G., & Lumsden, D. (2004). Communicating in groups and teams; Sharing leadership (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson. to get answers to pressing questions, or if you’d like establish your place in line to speak next. Be judicious and infrequent with interruptions, however.

- Paraphrase. Don’t just see if you can accurately reflect what a person is saying; see if you can determine if your understanding of the person’s “inner world” is accurate and whether you see things as the other person is experiencing them at the moment.

- Respond after listening, sincerely and constructively. Focus on content, ideas, & analysis rather than on personal matters.

- Allow for, and be careful how you interpret, silence. Keep in mind that people may have many reasons, positive or otherwise, for not speaking at a particular time.

In listening, don’t…

- Let listening be a dead end, in which you receive messages and don’t react at all.

- Allow the listening behavior of others to sway your own. If they’re inattentive, don’t lose your own focus; if they’re especially positive or negative, don’t lose your objectivity or critical ability.

- Cut off or put down a speaker.

- Interrupt excessively.

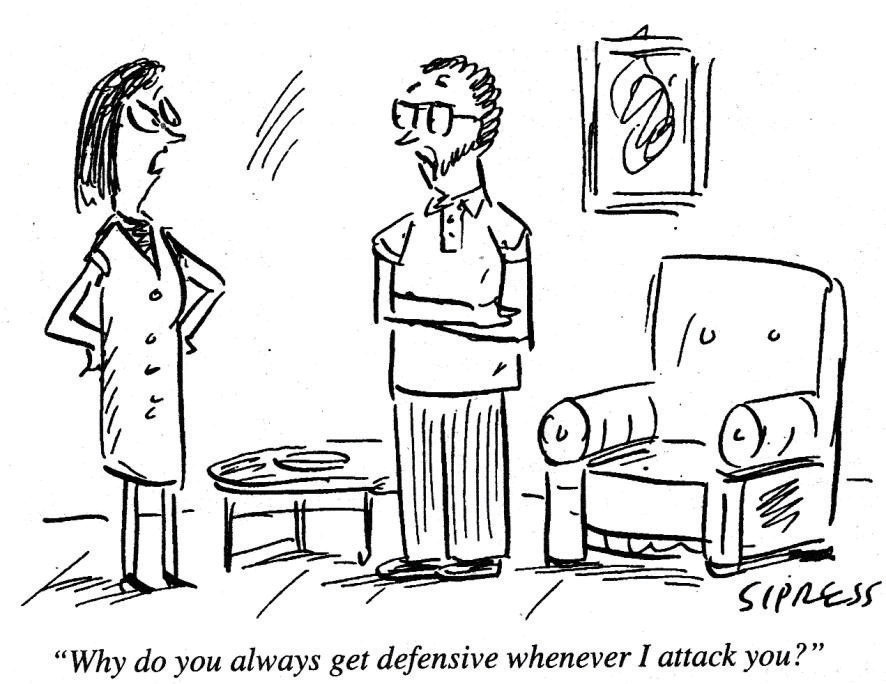

- Pose “counterfeit questionsA belligerent statement which appears superficially to be a question because its end with a question mark.”—belligerent statements masquerading as questions simply because they end with question marks.

- Allow the tone of someone’s message, or how agreeable you find the person to be, to color your interpretation or reactions to it.

- Express your interpretations of other people’s messages excessively. Why not? First of all, your interpretation may be wrong. Second, even if you’re right, you may arouse a defensive reaction that in turn leads to unproductive argumentation.

No matter how often you listen to people, and no matter how many groups you may be part of, each new listening situation will be unique. It’s your responsibility, shared with your fellow group members, to see that in each new conversation or discussion you exercise proper practices and skills in your listening.

Key Takeaway

To listen well in a group, it’s important to prepare properly and heed several dos and don’ts.

Exercises

- Observe a televised, recorded, or live group discussion. Identify the listening processes which furthered understanding and those which impeded it. What suggestions would you make to the members of the group to improve their listening? Which person in the discussion listened most effectively, and how did she or he accomplish that?

- Visit the website of the International Listening Association (http://www.listen.org) and read an article in one of the Association’s online publications. What discoveries did you make in your reading? How will you apply the discoveries to your future group interactions?

- Who’s the best listener you know? What does the person do (or not do) that makes him/her so effective? Give an example of how the person has listened well.