This is “Labor Unions”, section 7.6 from the book An Introduction to Business (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

7.6 Labor Unions

Learning Objective

- Explain why workers unionize and how unions are structured, and describe the collective-bargaining process.

As we saw earlier, Maslow believed that individuals are motivated to satisfy five levels of unmet needs (physiological, safety, social, esteem, and self-actualization). From this perspective, employees should expect that full-time work will satisfy at least the two lowest-level needs: they should be paid wages that are sufficient for them to feed, house, and clothe themselves and their families, and they should have safe working conditions and some degree of job security. Organizations also have needs: they need to earn profits that will satisfy their owners. Sometimes, the needs of employees and employers are consistent: the organization can pay decent wages and provide workers with safe working conditions and job security while still making a satisfactory profit. At other times, there is a conflict—real, perceived, or a little bit of both—between the needs of employees and those of employers. In such cases, workers may be motivated to join a labor unionOrganized group of workers that bargains with employers to improve its members’ pay, job security, and working conditions.—an organized group of workers that bargains with employers to improve its members’ pay, job security, and working conditions.

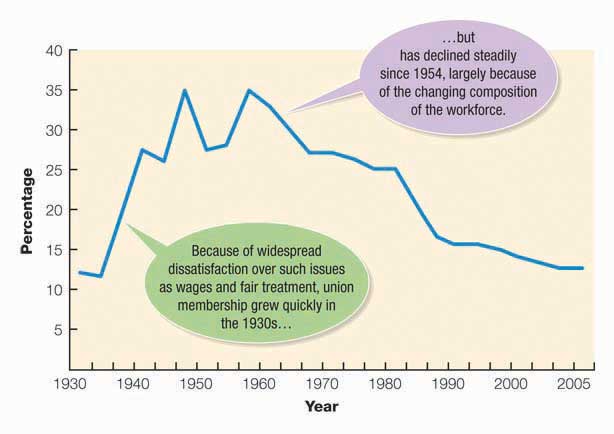

Figure 7.11 "Labor Union Density, 1930–2005" charts labor-union density—union membership as a percentage of payrolls—in the United States from 1930 to 2005. As you can see, there’s been a steady decline since the mid-1950s. Only membership among public workers (those employed by federal, state, and local governments, such as teachers, police, and firefighters) has remained steady, and, today, only about 12.5 percent of U.S. workers (about 10 percent in the private sector and 40 percent in the public sector) belong to unions.See Michael R. Carrell and Christina Heavrin, Labor Relations and Collective Bargaining: Cases, Practice, and Law, 7th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2004), 52–54.

Figure 7.11 Labor Union Density, 1930–2005

Why the decline? Many factors come into play. For one thing, there are more women in the workforce, and they’re more likely to work part-time or intermittently. In addition, we’ve shifted from a manufacturing-based economy characterized by large, historically unionized companies to a service-based economy made up of many small firms that are hard to unionize.U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Union Members in 2003” January 2004, http://www.bls.gov/cps (accessed December 30, 2004); U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Union Members Summary, January 20, 2006, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.nr0.htm (accessed May 6, 2006).

Union Structure

Unions have a pyramidal structure much like that of large corporations. At the bottom are locals that serve workers in a particular geographical area. Certain members are designated as shop stewards to serve as go-betweens in disputes between workers and supervisors. Locals are usually organized into national unions that assist with local contract negotiations, organize new locals, negotiate contracts for entire industries, and lobby government bodies on issues of importance to organized labor. In turn, national unions may be linked by a labor federation, such as the American Federation of Labor/Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL/CIO), which provides assistance to member unions and serves as the principal political organ for organized labor.

Collective Bargaining

In a nonunion environment, the employer makes largely unilateral decisions on issues affecting its labor force, such as salary and benefits. Management, for example, may simply set an average salary increase of 3 percent and require employees to pay an additional $50 a month for medical insurance. Typically, employees are in no position to bargain for better deals. (At the same time, however, for reasons that we’ve discussed earlier in this chapter, employers have a vested interest in treating workers fairly. A reputation for treating employees well, for example, is a key factor in attracting talented people.)

The process is a lot different in a union environment. Basically, union representatives determine with members what they want in terms of salary increases, benefits, working conditions, and job security. Union officials then tell the employer what its workers want and ask what they’re willing to offer. When there’s a discrepancy between what workers want and what management is willing to give—as there usually is—union officials serve as negotiators to bring the two sides together. The process of settling differences and establishing mutually agreeable conditions under which employees will work is called collective bargainingProcess by which management and union-represented workers settle differences..

The Negotiation Process

Negotiations start when each side states its position and presents its demands. As in most negotiations, these opening demands simply stake out starting positions. Both parties expect some give-and-take and realize that the final agreement will fall somewhere between the two positions. If everything goes smoothly, a tentative agreement is reached and then voted on by union members. If they accept the agreement, the process is complete and a contract is put into place to govern labor-management relations for a stated period. If workers reject the agreement, negotiators go back to the bargaining table.

Mediation and Arbitration

If negotiations stall, the sides may call in outsiders. One option is mediationApproach used to resolve a labor-contract dispute by following the recommendation of an impartial third party., under which an impartial third party assesses the situation and makes recommendations for reaching an agreement. A mediator’s advice can be accepted or rejected. If the two sides are willing to accept the decision of a third party, they may opt instead for arbitrationProcess of resolving a labor-contract dispute by having a third party study the situation and arrive at a binding agreement., under which the third party studies the situation and arrives at a binding agreement.

Grievance Procedures

Another difference between union and nonunion environments is the handling of grievancesUnion worker complaints on contract-related matters.—worker complaints on contract-related matters. When nonunion workers feel that they’ve been treated unfairly, they can take up the matter with supervisors, who may or may not satisfy their complaints. When unionized workers have complaints (such as being asked to work more hours than stipulated under their contract), they can call on union representatives to resolve the problem, in conjunction with supervisory personnel. If the outcome isn’t satisfactory, the union can take the problem to higher-level management. If there’s still no resolution, the union may submit the grievance to an arbitrator.

When Negotiations Break Down

At times, labor and management can’t resolve their differences through collective bargaining or formal grievance procedures. When this happens, each side may resort to a variety of tactics to win support for its positions and force the opposition to agree to its demands.

Union Tactics

The tactics available to the union include striking, picketing, and boycotting. When they go on strikeUnion tactic by which workers walk away from their jobs and refuse to return until a labor-management dispute has been resolved., workers walk away from their jobs and refuse to return until the issue at hand has been resolved. As undergraduates at Yale discovered when they arrived on campus in fall 2003, the effects of a strike can engulf parties other than employers and strikers: with four thousand dining room workers on strike, students had to scramble to find food at local minimarkets. The strike—the ninth at the school since 1968—lasted twenty-three days, and in the end, the workers got what they wanted: better pension plans.

Though a strike sends a strong message to management, it also has consequences for workers, who don’t get paid when they’re on strike. Unions often ease the financial pressure on strikers by providing cash payments. (Some unionized workers, by the way, don’t have the right to strike. Strikes by federal employees, such as air-traffic controllers, are illegal because they jeopardize the public interest.)

Figure 7.12

The adverse affects of a strike can impact management and workers alike.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

When you see workers parading with signs outside a factory or an office building (or even a school), they’re probably picketingUnion tactic of parading with signs outside a factory or other facility to publicize a strike.. The purpose of picketing is informative—to tell people that a workforce is on strike or to publicize some management practice that’s unacceptable to the union. In addition, because other union workers typically won’t cross picket lines, marchers can interrupt the daily activities of the targeted organization. How would you like to show up for classes to find faculty picketing outside the classroom building? In April 2001, faculty at the University of Hawaii, unhappy about salaries, went on strike for thirteen days. Initially, many students cheerfully headed for the beach to work on their tans, but before long, many more—particularly graduating seniors—began to worry about finishing the semester with the credits they needed to keep their lives on schedule.“Hawaii Professors End Strike,” USA Today, June 19, 2001, http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2001-04-18-hawaii.htm (accessed May 6, 2006).

The final tactic available to unions is boycottingMethod used by union members to voice displeasure with certain organizations by refusing to buy the company’s products and encouraging others to follow suit., in which union workers refuse to buy a company’s products and try to get other people to follow suit. The tactic is often used by the AFL/CIO, which maintains a national “Don’t Buy or Patronize” boycott list. In 2003, for example, at the request of two affiliates, the Actor’s Equity Association and the American Federation of Musicians, the AFL/CIO added the road show of the Broadway musical Miss Saigon to the list. Why? The unions objected to the use of nonunion performers who worked for particularly low wages and to the use of a “virtual orchestra,” an electronic apparatus that can replace a live orchestra with software-generated orchestral accompaniment.Union Label and Service Department, AFL/CIO, “AFL-CIO National Boycott List,” November–December 2004, http://www.unionlabel.org/boycott.jsp (accessed May 6, 2006).

Management Tactics

Management doesn’t sit by passively, especially if the company has a position to defend or a message to get out. One available tactic is the lockoutManagement tactic of closing the workplace to union workers.—closing the workplace to workers—though it’s rarely used because it’s legal only when unionized workers pose a credible threat to the employer’s financial viability. Another tactic is replacing striking workers with strikebreakersNonunion workers who are willing to cross picket lines to replace strikers.—nonunion workers who are willing to cross picket lines to replace strikers. Though the law prohibits companies from permanently replacing striking workers, it’s often possible for a company to get a court injunction that allows it to bring in replacement workers.

Lockout tactics were used in the 2004–2005 labor dispute between the National Hockey League (NHL) and the National Hockey League Players Association. When club owners and players failed to reach a salary agreement before the 2004 season, the owners imposed a lockout. Neither side would give in: the players wanted to retain a market-based salary system that let them negotiate salaries individually, while owners argued for a salary structure with some type of salary cap that would put a limit on total salaries. With the 2004–2005 season defunct, the NHL considered the option of declaring an impasse and bringing in replacement players (strikebreakers) for the next season. Though legally possible (at least in the United States), the action would certainly have been unpopular among the consumers of their product (the fans).National Hockey League Labor Dispute (2004), Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Hockey_League_labor_dispute_(2004) (accessed May 6, 2006).

The Future of Unions

As we noted earlier, union membership in the United States is declining. So, what’s the future of organized labor? Will membership continue to decline and unions lose even more power? The AFL/CIO is optimistic about union membership, pointing out recent gains in membership among women and immigrants, as well as health care workers, graduate students, and professionals.AFL-CIO, “How & Why People Join Unions,” Unions 101, http://www.aflcio.org/joinaunion/union101.cfm (accessed May 6, 2006).

But convincing workers to unionize is still more difficult than it used to be and could become even harder in the future. For one thing, employers have developed strategies for dissuading workers from unionizing—in particular, tactics for withholding job security. If unionization threatens higher costs for wages and benefits, they can resort to part-time or contract workers. They can also outsource work, eliminating jobs entirely, and more employers are now investing in technology designed to reduce the amount of human labor needed to produce goods or offer services.

Key Takeaways

- Some workers belong to labor unions—organized groups of workers that bargain with employers to improve members’ pay, job security, and working conditions.

-

Unions have a pyramidal structure. At the bottom are locals, who serve workers in a particular geographical area.

- Locals are usually organized into national unions that assist with local contract negotiations and negotiate industry-wide contracts.

- Nationals may be linked by a labor federation, such as the AFL/CIO, which provides assistance to member unions and serves as the principal political organ for organized labor.

-

When there’s a discrepancy between what workers want in terms of salary increases, benefits, working conditions, and job security and what management is willing to give, the two sides engage in a process called collective bargaining.

- If everything goes smoothly, a contract is soon put into place.

- If negotiations break down, the sides may resort to mediation (in which an impartial third party makes recommendations for reaching an agreement) or arbitration (in which the third party imposes a binding agreement).

- When unionized workers feel that they’ve been treated unfairly, they can file grievances—complaints over contract-related matters that are resolved by union representatives and employee supervisors.

-

If labor differences can’t be resolved through collective bargaining or formal grievance procedures, each side may resort to a variety of tactics. The union can do the following:

- Call a strike (in which workers leave their jobs until the issue is settled)

- Organize picketing (in which workers congregate outside the workplace to publicize their position)

- Arrange for boycotting (in which workers and other consumers are urged to refrain from buying an employer’s products)

- Management may resort to a lockout—closing the workplace to workers—or call in strikebreakers (nonunion workers who are willing to cross picket lines to replace strikers).

Exercises

- You’ve just gotten a job as an autoworker. Would you prefer to work in a unionized or nonunionized plant? Why? If you were hired as a high-level manager in the company, would you want your workers to be unionized? Why, or why not? What’s your opinion on the future of organized labor? Will union membership grow or decline in the next decade? Why, or why not?

- What happens in a unionized company when negotiations between labor and management break down? Identify and describe the tactics that unions can use against management and those that management can use against unions.