This is “What Is an Entrepreneur?”, section 5.1 from the book An Introduction to Business (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

5.1 What Is an Entrepreneur?

Learning Objectives

- Define entrepreneur.

- Describe the three characteristics of entrepreneurial activity.

- Identify five potential advantages to starting your own business.

- Explain the differences among three types of start-up firms.

In developing BTIO and Realityworks Inc., the Jurmains were doing what entrepreneurs do (and doing it very well). In fact, Mary was nominated three times for the Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year Award and named 2001 Wisconsin Entrepreneurial Woman of the Year by the National Association of Women Business Owners. So what, exactly, is an entrepreneur? What does an entrepreneur do? According to one definition, an entrepreneur is an “individual who starts a new business,” and that’s true as far as it goes. Another definition identifies an entrepreneur as someone who uses “resources to implement innovative ideas for new, thoughtfully planned ventures”Canadian Foundation for Economic Education, “Glossary of Terms,” Mentors, Ventures & Plans (2008), http://www.mvp.cfee.org/en/glossary.html (accessed October 7, 2008). which is also true as far as it goes. But an important component of a satisfactory definition is still missing. To appreciate fully what it is, let’s go back to the story of the Jurmains, for whom entrepreneurship seems to have worked out quite well. We hasten to point out that, in 1993, the Jurmains were both unemployed—Rick had been laid off by General Dynamics Corp., and Mary by the San Diego Gas and Electric Company. While they were watching the show about teenagers and flour sacks, they were living off a loan from her father and the returns from a timely investment in coffee futures. Rick recalls that the idea for a method of creating BTIO came to him while “I was awake in bed, worrying about being unemployed.” He was struggling to find a way to feed his family. He had to make the first forty simulators himself, and at the end of the first summer, BTIO had received about four hundred orders—a promising start, perhaps, but, at $250 per baby (less expenses), not exactly a windfall. “We were always about one month away from bankruptcy,” recalls Mary.

At the same time, it’s not as if the Jurmains started up BTIO simply because they had no “conventional” options for improving their financial prospects. Rick, as we’ve seen, was an aerospace engineer, and his résumé includes work on space-shuttle missions at NASA. Mary, who has not only a head for business but also a degree in industrial engineering, has worked at the Johnson Space Center. Therefore, the idea of replacing a sack of flour with a computer-controlled simulator wasn’t necessarily rocket science for the couple. But taking advantage of that idea—choosing to start a new business and to commit themselves to running it—was a risk. Risk taking is the missing component that we’re looking for in a definition of entrepreneurship, and so we’ll define an entrepreneurIndividual who identifies a business opportunity and assumes the risk of creating and running a business to take advantage of it. as someone who identifies a business opportunity and assumes the risk of creating and running a business to take advantage of it.

The Nature of Entrepreneurship

If we look a little more closely at the definition of entrepreneurship, we can identify three characteristics of entrepreneurial activity:Adapted from Marc J. Dollinger, Entrepreneurship: Strategies and Resources, 3rd ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003), 5–7.

- Innovation. Entrepreneurship generally means offering a new product, applying a new technique or technology, opening a new market, or developing a new form of organization for the purpose of producing or enhancing a product.

- Running a business. A business, as we saw in Chapter 1 "The Foundations of Business", combines resources to produce goods or services. Entrepreneurship means setting up a business to make a profit.

- Risk taking. The term risk means that the outcome of the entrepreneurial venture can’t be known. Entrepreneurs, therefore, are always working under a certain degree of uncertainty, and they can’t know the outcomes of many of the decisions that they have to make. Consequently, many of the steps they take are motivated mainly by their confidence in the innovation and in their understanding of the business environment in which they’re operating.

It isn’t hard to recognize all three of these characteristics in the entrepreneurial experience of the Jurmains. They certainly had an innovative idea. But was it a good business idea? In a practical sense, a “good” business idea has to become something more than just an idea. If, like the Jurmains, you’re interested in generating income from your idea, you’ll probably need to turn it into a product—something that you can market because it satisfies a need. If—again, like the Jurmains—you want to develop a product, you’ll need some kind of organization to coordinate the resources necessary to make it a reality (in other words, a business). Risk enters the equation when, like the Jurmains, you make the decision to start up a business and when you commit yourself to managing it.

A Few Things to Know about Going into Business for Yourself

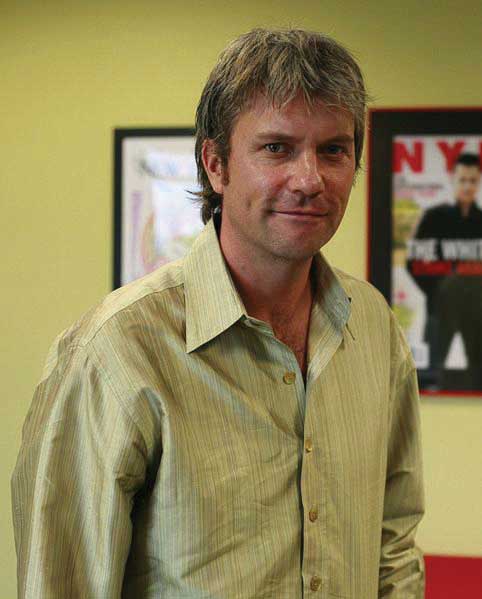

Figure 5.1

Do you think Chris DeWolfe knew what a huge success MySpace would be when he and Tom Anderson started their Web site?

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chris_DeWolfe.jpg accessed Feb. 2, 2009.

So what about you? Do you ever wonder what it would be like to start your own business? Maybe you want to try your hand at entrepreneurship. You could be the next Tom Anderson or Chris DeWolfe, founders of MySpace. Or the next David Marcks, a golf course manager who came up with the idea of Geese Police—training dogs to chase geese from golf courses, corporate parks, and municipal playgrounds.Isabel M. Isidro, “Geese Police: A Real-Life Home Business Success Story,” PowerHomeBiz.com (2008), http://www.powerhomebiz.com/OnlineSuccess/geesepolice.htm (accessed October 8, 2008). Or even the next Pierre Omidyar, the French-born software developer who built an online venue for person-to-person auctions, known as eBay.See American Academy of Achievement, “Pierre Omidyar,” Academy of Achievement (November 9, 2005), http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/omi0bio-1 (accessed October 8, 2008). You might even turn into a “serial entrepreneur,” like Dan Bricklin, whose résumé so far includes four software companies: Software Arts (founded to market his own invention, an electronic spreadsheet calculator), Software Garden (software for monitoring Web servers), Slate Corp. (software for pen computers), and Trellix Corp. (software for building and hosting Web sites).Dan Bricklin, Dan Bricklin’s Web site, http://www.bricklin.com (accessed October 8, 2008); Dan Bricklin, “Natural-Born Entrepreneur—Lessons of a Serial Entrepreneur,” Working Knowledge (October 22, 2001), http://hbswk.hbs.edu/archive/2569.html (accessed October 8, 2008).

For the sake of argument, let’s say that you would like to know a little more about going into business for yourself—in which case, you’ll want some answers to questions like the following:

- Should I start a business?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of starting a business?

- How do I come up with a business idea?

- Should I build a business from scratch, buy an existing business, or invest in a franchise?

- How do I go about planning a business?

- What steps are involved in developing a business plan?

- Where would I find help in getting my business started and operating it through the start-up phase?

- How can I increase the likelihood that I’ll succeed?

In this chapter, we’ll provide some answers to questions like these.

Why Start Your Own Business?

Let’s say that you are interested in the idea of going into business for yourself. Not everyone, of course, has a desire to take the risks and put in the work involved in starting up a business. What sort of characteristics distinguishes those who do from those who don’t want to start a business? Or, more to the point, why do some people actually follow through on the desire to start up their own businesses? According to the Small Business Administration (SBA)Government agency that helps prospective owners set up small businesses, obtain financing, and manage ongoing operations., a government agency that provides assistance to small businesses, the most common reasons for starting a business are the following:U.S. Small Business Administration, “First Steps: How to Start a Small Business,” http://www.sba.gov/starting/indexsteps.html (accessed April 21, 2006).

- To be your own boss

- To accommodate a desired lifestyle

- To achieve financial independence

- To enjoy creative freedom

- To use your skills and knowledge

The SBA points out, though, that these are likely to be advantages only “for the right person.” And how do you know if you’re one of the “right people”? The SBA suggests that you assess your strengths and weaknesses by asking yourself a few relevant questions:U.S. Small Business Administration, “Is Entrepreneurship for You?” http://www.sba.gov/smallbusinessplanner/plan/getready/SERV_SBPLANNER_ISENTFORU.html (accessed October 26, 2008).

- Am I a self-starter? You’ll need to develop and follow through on your ideas. You’ll need to be able to organize your time.

- How well do I get along with different personalities? You’ll need to develop working relationships with a variety of people, including unreliable vendors and sometimes cranky customers.

- How good am I at making decisions? You’ll be making decisions constantly—often under pressure.

- Do I have the physical and emotional stamina? Can you handle six or seven workdays of as long as twelve hours every week?

- How well do I plan and organize? If you can’t stay organized, you’ll get swamped by the details. In fact, poor planning is the culprit in most business failures.

- Is my drive strong enough? You’ll need to be highly motivated to withstand bad periods in your business, and simply being responsible for your business’s success can cause you to burn out.

- How will my business affect my family? Family members need to know what to expect before you begin a business venture, such as financial difficulties and a more modest standard of living.

Later in this chapter, we’ll take up the question of why businesses fail, but since we’re still talking about the pros and cons of starting a business in the first place, we should consider one more issue: in addition to the number of businesses that start and then fail, a huge number of business ideas never even make it to the grand opening. One business analyst cites four reservations (or fears) that prevent people from starting businesses:Shari Waters, “Top Four Reasons People Don’t Start a Business,” About.com, http://retail.about.com/od/startingaretailbusiness/tp/overcome_fears.htm (accessed October 8, 2008).

- Money. Granted, without the cash, you can’t get very far. What to do: Conduct some research to find out where funding is available.

- Security. A lot of people don’t want to sacrifice the steady income that comes with the nine-to-five job. What to do: Don’t give up your day job. At least at first, think about hiring someone to run your business while you’re gainfully employed elsewhere.

- Competition. A lot of people don’t know how to distinguish their business ideas from similar ideas. What to do: Figure out how to do something cheaper, faster, or better.

- Lack of ideas. Some people simply don’t know what sort of business they want to get into. What to do: Find out what trends are successful. Turn a hobby into a business. Think about a franchise.

If you’re still interested in going into business for yourself, feel free to regard these potential drawbacks as mere obstacles to be overcome by a combination of planning and creative thinking.

Distinguishing Entrepreneurs from Small Business Owners

Figure 5.2

These bakers are not entrepreneurs. They run their small bakery for the sole purpose of providing an income for themselves and their families (a salary-substitute firm) or to earn a living while pursuing their hobby of baking (a lifestyle firm).

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Though most entrepreneurial ventures begin as small businesses, not all small business owners are entrepreneurs. Generally speaking, we can divide small businesses into three types:Adapted from Bruce R. Barringer and R. Duane Ireland, Entrepreneurship: Successfully Launching New Ventures, 2nd ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2008), 16.

- Salary-substitute firms are started to provide owners with incomes similar to those that they’d be earning while working for an employer. Typically, they offer common products—retail merchandise, for example, or a service like accounting or hairstyling. Most small businesses are of this type.

- As the name suggests, people start lifestyle firms to earn a living while pursuing a particular lifestyle. These businesses often reflect owners’ hobbies or favorite pursuits—say, surf shops or rock-climbing excursions. As a rule, they don’t do anything innovative, and they don’t need to grow very fast.

- Like BTIO, entrepreneurial firms bring innovative products to market. Like the Jurmains, owners are people who recognized an opportunity and developed a product to satisfy the needs of certain customers. Their goal is to grow the business and eventually expand into other markets.

Key Takeaways

- An entrepreneur is someone who identifies a business opportunity and assumes the risk of creating and running a business to take advantage of it.

-

There are three characteristics of entrepreneurial activity:

- Innovating. An entrepreneur offers a new product, applies a new technique or technology, opens a new market, or develops a new form of organization for the purpose of producing or enhancing a product.

- Running a business. Entrepreneurship means setting up a business to make a profit from an innovative product or process.

- Risk taking. Risk means that an outcome is unknown. Entrepreneurs, therefore, are always working under a certain degree of uncertainty, and they can’t know the outcomes of many of the decisions that they have to make.

-

According to the SBA, a government agency that provides assistance to small businesses, there are five advantages to starting a business—“for the right person”:

- Be your own boss.

- Accommodate a desired lifestyle.

- Achieve financial independence.

- Enjoy creative freedom.

- Use your skills and knowledge.

-

To determine whether you’re one of the “right people” to exploit the advantages of starting your own business, the SBA suggests that you assess your strengths and weaknesses by asking yourself the following questions:

- Am I a self-starter?

- How well do I get along with different personalities?

- How good am I at making decisions?

- Do I have the physical and emotional stamina?

- How well do I plan and organize?

- Is my drive strong enough?

- How will my business affect my family?

-

Though most entrepreneurial ventures begin as small businesses, not all small business owners are entrepreneurs. Generally speaking, we can divide small businesses into three types:

- Salary-substitute firms are started to provide owners with incomes similar to those that they’d be earning while working for employers.

- People start lifestyle firms to earn a living while pursuing a particular lifestyle; they often reflect owners’ hobbies or favorite pursuits.

- Entrepreneurial firms bring innovative products to market; owners are people who recognized an opportunity and developed a product to satisfy the needs of certain customers.

Exercise

(AACSB) Analysis

Do you have what it takes to be an entrepreneur? To find out, start by reviewing the following list of characteristics commonly attributed to entrepreneurs:

- They are creative people who sometimes accomplish extraordinary things because they’re passionate about what they’re doing.

- They are risk-taking optimists who commit themselves to working long hours to reach desired goals.

- They take pride in what they’re doing and get satisfaction from doing something they enjoy.

- They have the flexibility to adjust to changing situations to achieve their goals.

We’ll also add that entrepreneurs usually start small. They begin with limited resources and build their businesses through personal effort. At the end of the day, their success depends on their ability to manage and grow the organization that they created to implement their vision.

Now use the following three-point scale to indicate the extent to which each of these attributes characterizes you:

- It doesn’t sound like me.

- It sounds like me to a certain extent.

- It sounds a lot like me.

Based on your responses, do you think that you have the attributes of an entrepreneur? Do you think you could be a successful entrepreneur? Why, or why not?