This is “Decision Making”, section 4.4 from the book Advertising Campaigns: Start to Finish (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

4.4 Decision Making

Learning Objectives

After studying this section, students should be able to do the following:

- Demonstrate an ability to match the decision process model with a purchase decision.

- Describe the various consumer behavior models based on motivation.

Understanding how we make decisions helps advertisers choose the right message to send at the right time.

The Decision-Making Process

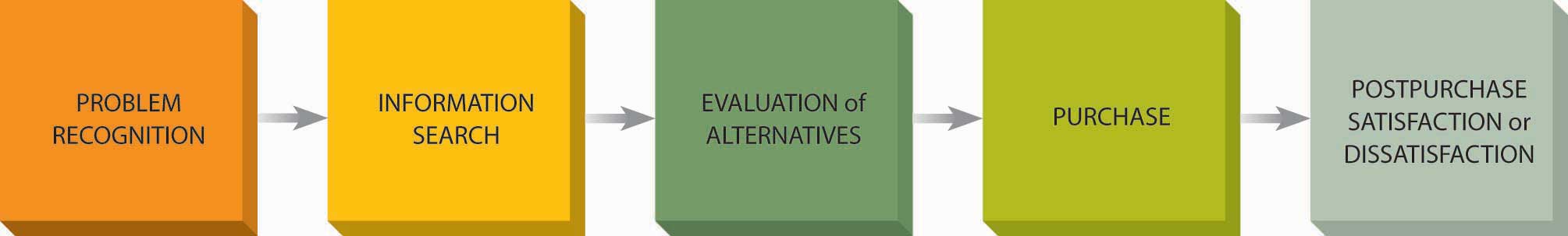

The decision to purchase a product has five stages, each of which implies the need for a different type of communication. The five stages are:

- Need recognitionThe first step in the buying decision process; the realization that we have a need for a product.: first, we realize we have a need for a product. Advertising for this stage may highlight an unmet need, a common life problem, or a desirable new capability.

- Information searchProcess in which consumers seek out information about a product before buying, for example by searching the Web or asking friends.: we seek out information about the product by searching the Web or asking friends. Informative advertising can demonstrate product performance or superiority.

- Evaluation of alternativesProcess in which, before buying, consumers compare the choices available based on various attributes.: we compare the choices available based on various attributes. Comparative ads and two-sided messages spell out the pros (and to a lesser extent the cons) of an advertiser’s brand versus competing brands.

- PurchaseProcess in which consumers choose the option they like best and buy it.: we choose the option we like best and buy it. Ads facilitate purchase by telling us where or how to buy, or perhaps they announce a price reduction for the product.

- Postpurchase satisfaction or dissatisfactionThe process in which consumers use a new product and are either satisfied with the purchase or not.: we use the product and we’re either satisfied with the purchase or not. Postsale communications, such as feedback and social networks, help consumers confirm their choices or resolve issues.

Figure 4.8 The Decision-Making Process

Advertisers can help consumers through the decision-making process. Some ads intend to create awareness that a need exists (it was an adman, not a doctor, who invented the term “halitosis” to describe bad breath!). Other ads provide information to facilitate information search and comparisons. Progressive Insurance, for example, lets customers shop online and compare prices among major competitors. The company does not promise to have the lowest price, but it makes clear what its price is in relation to the competition. This is particularly helpful in the “evaluation of alternatives” stage as customers compare different competitive offerings.Nancy Michael, “Customer Loyalty: Elusive, but Critical,” ABA Banking Journal 99, no. 2 (2007): 42.

Who Decides?

The people who make the purchase decision can be individuals, couples, families, or businesses. In businesses, the “buying centerA group of people in a business who are involved in the decision-making process for corporate purchases.” (a group of people tasked with making purchase decisions on behalf of the organization) typically is involved in the decision-making process because organizational decisions are more complex. Each member of the buying center plays a different role in the process, which may require different types of messages. For example, new corporate computer software might advertise how it enhances business performance for managers while it emphasizes technical sophistication for IT professionals.

SS+K’s client, the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, has many audiences ranging from individuals to small businesses to national accounts (companies with over five hundred people, sometimes in multiple states). The agency recently designed a campaign to address the needs of national accounts business decision makers (the HR or corporate group in charge of making insurance decisions for a corporation.)

Dig Deeper

Ariba, a provider of procurement and spending management software and services, sells to organizations such as banks. Ariba has learned that marketing to banks means understanding their priorities and challenges. Banks tend to be more conservative in their software purchase decisions because buying software often requires being able to roll it out across different branch locations. Purchasing agents at banks want to know if the manufacturer will support the product across locations and if it can be scaled quickly to other regions or departments. They want to know that the software will improve their bottom line and that others have deployed it successfully.Roger Slavens, “Understand Client Priorities, Then Deliver Solutions” B to B, March 12, 2007, 24.

Interview people whose jobs include the responsibility of purchasing items for their businesses to use. Ask them how they go about making these decisions, and what information sources they consult in this process. How important are criteria such as brand name, reputation, cutting-edge features, and color?

Models of Decision Making

MotivationThe processes that lead people to behave as they do. refers to the processes that lead people to behave as they do. For example, why do consumers decide to buy a timeshare vacation property? An industry survey found that the most important reasons to purchase a timeshare include flexibility, low cost, a desirable resort, and the certainty of quality accommodation.Beverley Sparks, Ken Butcher, and Grace Pan, “Understanding Customer-Derived Value in the Timeshare Industry,” Cornell Hotel & Restaurant Administration Quarterly 48 (February 2007): 28. It’s important that advertisers understand what drives customers so they can design messages to address central concerns rather than minor ones.

Involvement and Perceived Risk

One important driver is a consumer’s extent of involvementThe amount of thought and effort a consumer puts into a buying decision. with a brand or product category. It’s tempting to assume that we put more thought into purchases that are expensive, but this isn’t necessarily true. We might be motivated to put a great deal of thought and effort into choosing even a relatively cheap product if we feel our choice will reflect something about ourselves to others.

And involvement often is a function of the product’s degree of perceived riskThe potential physical, financial, or social drawbacks that a consumer can imagine in making the wrong buying decision.:

- Physical risk. Will the wrong choice endanger my health or that of my family?

- Financial risk. Will the wrong choice cost me too much money?

- Social risk. Will the wrong choice embarrass me or lead to the wrong impression?

Heuristics: Rules of Thumb

Hershey or Nestlé? Coke or Pepsi? Charmin or Bounty? Lil Wayne or Usher? People don’t have the time or desire to ponder endlessly about every purchase. HeuristicsShortcuts or mental “rules of thumb” that people use in making a decision. are shortcuts or mental “rules of thumb” that we use when we make a decision—especially when we choose among products in a category where we don’t see huge differences or if the outcome isn’t do or die. These rules simplify the decision-making process by making it quick and easy. Common heuristics include these:

- Save the most money. Many people follow a rule like, “I’ll buy the lowest-priced choice so that I spend the least money right now.” Using this heuristic means you don’t need to look beyond the price tag to make a decision. Wal-Mart built a retailing empire by pleasing shoppers who follow this rule.

- You get what you pay for. Others might use the opposite heuristic, namely, “I’ll buy the more expensive product, because higher price often means better quality.” These consumers are influenced by ads alluding to exclusivity, quality, and uncompromising performance.

- Stick to the tried and true. Brand loyaltyA heuristic that simplifies the decision-making process for consumers: they buy the brand that they’ve always bought before. also simplifies the decision-making process—we buy the brand that we’ve always bought before, and thus we don’t need to spend more time and effort on the decision. It’s hard to downplay the importance of brand loyalty—and of the role that advertising plays in creating and maintaining it. In a study of the market leaders in thirty product categories, twenty-seven of the brands that were number one in 1930 (such as Ivory Soap and Campbell’s Soup) still were at the top over fifty years later.Richard W. Stevenson, “The Brands with Billion-Dollar Names,” New York Times, October 28, 1988, A1. Clearly “choose a well-known brand name” is a powerful heuristic.

Key Takeaway

Some purchases matter to us a lot more than others, so it makes sense that we don’t devote the same amount of attention to advertising for every idea, product, or service. An advertiser needs to appreciate how involved her customers are likely to be; we are more likely to search out detailed information for products that are highly involving to us. In other cases we tend to fall back on heuristics, “rules of thumb” that reflect well-learned rules (such as “it must be better if it costs more”).

Exercises

- Take a common product or service and demonstrate the decision-making process that an average consumer would go through when purchasing it.

- Consumer motivation is very important to marketers and advertisers. Describe how involvement and perceived risk are used to heighten consumer motivation.

- What is a heuristic? How do marketers and advertisers use heuristics to achieve brand loyalty?