This is “Advertising and Society”, chapter 3 from the book Advertising Campaigns: Start to Finish (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 3 Advertising and Society

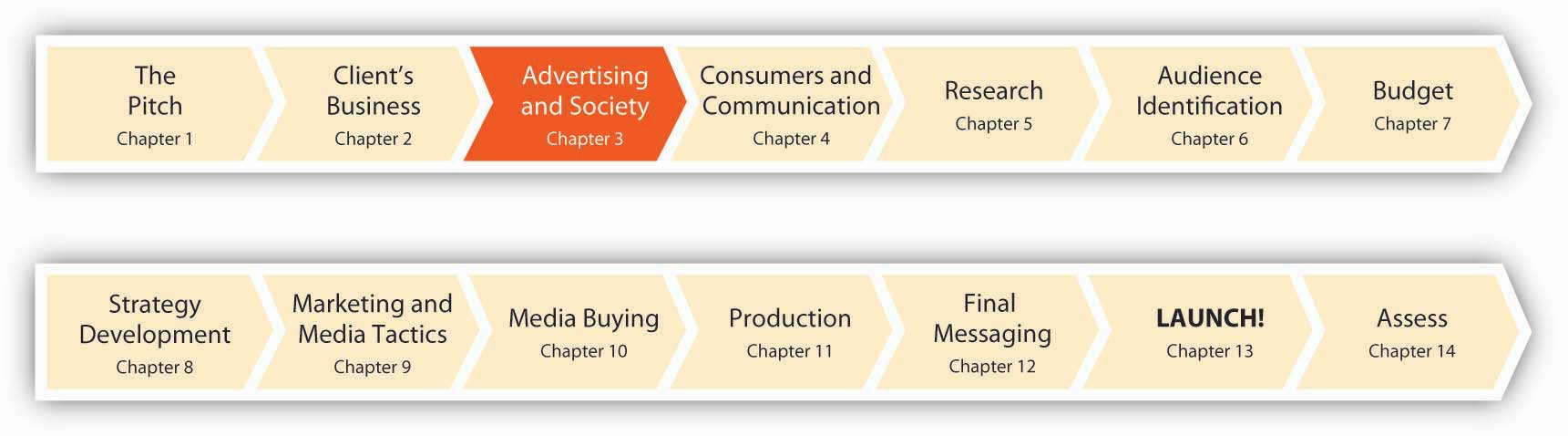

Figure 3.1 Build a Foundation

Advertising is part of the glue that holds our culture together. It allows us to share a common experience in a landscape populated (for better or worse) by brands, images, logos, and even silly jingles. We define who we are by what we buy and wear because we know that others judge us by what we buy and wear. And advertising influences those judgments. “We understand each other not by sharing religion, politics, or ideas. We share branded things. We speak the Esperanto of advertising, luxe populi,” says advertising professor and commercial culture observer James Twitchell.James Twitchell, Living It Up: Our Love Affair with Materialism (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002), xv.

Advertising is a sort of “commercialized gossip,” a collection of stories that companies tell customers about their products in order to make them distinguishable from one another. Some brands do such a good job of holding our attention that they become cultural icons in their own right—Apple, Nike, even the lowly Charmin (where would we be without Mr. Whipple?), and the Keebler Elves. And in collectively listening to the commercialized gossip and buying the associated products, consumers align themselves with the images and stories, knowing that other consumers will know those same stories.

The cultural dimension of advertising came of age in the 1920s. Agencies and publicists no longer sought merely to convey objective facts about the products—they sought to link products with a particular lifestyle, imbue them with glamour and prestige, and persuade potential consumers that purchasing an item could be, as historian Alan Brinkley describes it, “a personally fulfilling and enriching experience.”Alan Brinkley, American History: A Survey (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1991), 648. The images of ads sought to both resonate with and help define the lifestyles of those who bought the products.

People seek to differentiate themselves, so much so that a particular kind of advertising—called dog whistle advertisingAdvertising that works like an inside joke, targeting a particular group with messages only that group can hear and appreciate.—targets a group with messages only that group can hear and appreciate. Like an inside joke, these ads reinforce a sense of belonging to the group and show that the advertised company “gets it” too. For example, Apple’s “Rip, Mix, Burn” campaign, which targeted young computer users with a message of ease-of-use of its iTunes music software, alluded to the prevailing (and illegal) practice of music sharing among that group.

Video Highlight

Rip, Mix, Burn

(click to see video)This commercial for iTunes speaks directly to the target audience with words only they understand.

In many ways—for better or for worse—modern advertising may be the most significant U.S. contribution to global culture. Sociologist Andrew Hacker calls advertising “this country’s most characteristic institution.”Quoted in Stephen Fox, The Mirror Makers: A History of American Advertising and Its Creators (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1997), cover quote. But, to say the least, this contribution is not without controversy. Critics claim that ads manipulate the public into wasting money on unneeded products. Some say advertising has corrupted holidays like Christmas and Thanksgiving, making the season a time of materialism rather than a deeper celebration of thankfulness. There’s even a common rumor that Coca-Cola invented the modern-day Santa Claus (http://www.snopes.com/cokelore/santa.asp). Others just want to hide from the commercial messages that bombard them at every turn and enjoy some peace and quiet. Let’s take an objective look at advertising, warts and all.