This is “Considering the Broader Significance”, section 4.2 from the book A Guide to Perspective Analysis (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

4.2 Considering the Broader Significance

Learning Objectives

- Discuss how to reveal the broader significance of the analysis—personal, cultural, and scholarly.

- Explain how to avoid clichés and broad declarative statements.

- Reveal heuristics that help us explore the significance.

By now you should have a pretty good idea of how to look carefully at your subject, come up with key assertions, find specific examples to illustrate these assertions, and justify your point of view through a close reading. Yet there is still one more area of analysis that we need to discuss: the significance. Sadly, this is the area most often overlooked in school because the answer to the question “Why are you writing the essay?” is so obvious—“Duh, because my teacher told me to.” However, without significance an essay simply becomes an interpretation, which by itself may not mean anything other than an excuse to show off how clever you are. Just as spices give flavor to food, significance is the ingredient that turns an interpretation into a perspective that is meaningful for both the writer and the audience. In fact, outside of school, the primary motivation for engaging in analysis is not to simply show off the ability to discern patterns in a subject, but to call attention to something of wider importance. In exploring the significance, you reveal how the process of analysis engenders new insights about your personal beliefs and experiences as well as the wider cultural concerns that surround both you and your subject.

Whether you choose to explore the personal, cultural, or academic significance of your subject, you will move in the reverse direction from how you derived your explanation. To illustrate, let’s return to The Wizard of Oz for a moment. If I were to use a personal experience to explain how I see one of the key scenes, it might write:

When I was a kid, I always felt intimidated by my teachers. To me they seemed like the fiery machine version of Oz—powerful, untouchable, and all knowing. However, when my mom became friends with my third grade teacher, and I got to know her outside of class, I discovered that she didn’t know everything and had problems just like the rest of us. So when Toto exposes the man behind the curtain, it reminds me of how quickly authority can vanish in the harsh light of reality.

However, to make my analysis significant, I would need to discuss the implications of this further:

You might think that I lost respect for my teacher as I got to see more of her imperfections, but in fact I ended up liking her more, just as I’ve always preferred the humble, human version of Oz to his fiery alter ego. I wish that more authority figures would stop pretending and admit that they don’t know everything. In my experience, people who talk and act with absolute certainty tend to be mediocre teachers and leaders; I have much greater respect for those who aren’t afraid to utter the phrase “I don’t know” once in awhile.

In short, while your explanations justify your perspectives through a discussion of the relevant details contained within your subject, the significance reveals the insights this leads you to discover in other related areas.

Thinking Beyond Clichés and Obvious Classifications

Though there are no hard and fast rules concerning how much you should explore the significance, you should at least take your observations beyond the obvious and cliché. Sometimes clichés don’t make any sense at all; we just repeat them ourselves because we hear others constantly utter them. When I was a child, anytime I would complain that something isn’t fair, my parents would often respond with the cliché “life isn’t fair.” Though I often repeated the phrase myself (especially when I started teaching), I have since decided that it doesn’t really make any sense. “Life” is too big to be broadly characterized as “fair” or “unfair”; instead we all experience countless moments of both justice and injustice. And even if life isn’t fair, that’s no reason for us to act unjustly. We may not have the ability to fix all the seemingly random sufferings that come with living, but we can at least strive to behave in a reasonable manner ourselves.

Other times, clichés become clichés because they are often true, but this does not mean that they are always true for all occasions. In fact, for every cliché you can come up with, you can find another that has the opposite meaning. “Absence can make the heart grow fonder,” but often loved ones who are “out of sight are out of mind.” “Good things may come to those who wait,” but “it’s the early bird that gets the worm.” “The grass may be greener on the other side,” but, as Dorothy reminds us, “there’s no place like home.” And not only can clichés seem contradictory, but also suggest a person’s desire not to think. For instance, if you were having problems with a long distance relationship and asked your roommates for advice, you probably would not want them to simply reply “absence makes the heart grow fonder.” Such a response would imply that they didn’t care enough about you to take into account the specific concerns of your particular situation. Likewise, readers often feel the same way when a cliché substitutes for more detailed significance.

Along with a tendency to overuse clichés, the other factor that prevents writers from thinking very deeply about the implications of their subject occurs when they rely too much on those statements of classification and taste discussed in the previous chapter. When exploring the significance, try not to simply label your subject as “ironic,” or “absurd,” and leave it at that, but also consider why it matters that we see it this way. For instance, you could discuss how certain aspects remind you of an absurdity in your own life that needs correcting. In short, try to move beyond simply showing that you understand the surface meaning of these terms to fully exploring the wider insights that they helped you to discover. If you only rely on a cliché or broad declarative statement, the significance of your essay may disappoint your reader like an unsatisfying punch line to a joke that took forever to set up.

One way to move beyond simple declarative statements or clichés is to brainstorm on what you already know about the significance of your focus. “Brainstorming”A method of exploring the implications of a subject by quickly writing down everything it makes you think of and then organizing the associations into categories. or “listing” is a widely used heuristic in which you quickly write down all the thoughts and associations that you have on a subject to see where the ideas may lead you. To give your mind free reign, you should not pause to censor any of the ideas because sometimes the ones that seem the most bizarre initially can lead to your most profound insights. Consider, for instance, the following brainstorm on the nature and implications of advertisements for laptops:

It’s easy to look like I’m working

Work anywhere I like

Better than carrying a stack of heavy books

Always connected to my friends and fun stuff

Make it my favorite color and it’ll look cool

After doing this for several minutes, you should then look over your jottings to see if any patterns appear. For instance, from my notes above you can see how these commercials might let students think that laptops make it easy for them to look intellectual and do their work in bits and pieces. In addition, this implies that they can use this one product to manage the “lighter side” of their lives—social interactions and relaxation (reading, watching movies).

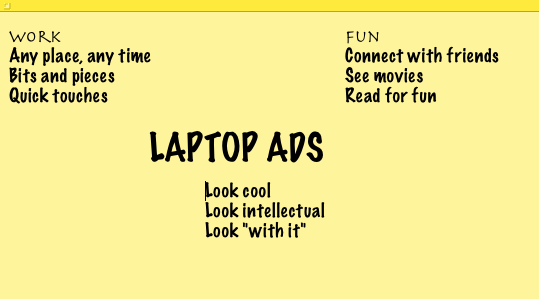

For those of you who tend to think in concepts before considering the concrete details, you might try clusteringA method of exploring the implications of a subject by first writing down the general categories that relate to it and then listing the specific details that make up these categories. (sometimes referred to as “looping” or “a spider diagram”), a variation of brainstorming in which you move in the opposite direction, from categories to specific instances (and, again, list everything that comes to mind without censorship). In this version, you first write down the main topic you wish to examine in the middle of a piece of paper, surround this topic with the major issues and concerns that come to mind when you think of it, and then surround these issues with the concrete details that they consist of. For instance a cluster around the topic of commercials for laptops might look like this:

Notice that while the layout is different, the considerations appear similar to the ones that emerged while brainstorming. It doesn’t really matter which form you use or how you use it, as long as it sparks new insights.

After taking time out to explore the significance, you can then return to your analysis to integrate your new insights about the broader implications of your piece:

There’s little doubt that laptop advertisements work—or companies wouldn’t continue to use these same tired plots. Typically we see a group of “with it” people— young students at a desk, on the grass or at a coffee shop; well-groomed professionals having success at a business meeting; young children looking at movies or educational learning programs. The laptops may be coordinated to their style or type of clothing (for instance, black or gray for a businessman; red for a college student; pink for a little girl). While people may like what they “see”, the ads don’t necessarily focus on what a laptop really helps you do—preparing work, researching and rewriting presentations or conducting appropriate due diligence on research findings. This same focus on style over substance permeates much of our culture, from politicians who say that they are against government spending while increasing their personal salaries and staff to the students who paste “Go Green” bumper stickers to their unnecessarily large, gas guzzling cars.

The paragraph is much more intriguing than it would be if you tried to sum up the significance too quickly by relying on a cliché: "Buyer Beware." If you think carefully about both the piece and the issues it raises before writing about it more formally, you will develop a much more satisfying discussion of its significance.

The Personal Significance

When looking at the personal significance, it’s helpful to remind yourself that you need to be careful of not overdoing it. A reason that teachers often tell students not to use “I” is that it often encourages them to only talk about themselves and leave the subject behind, leading to the dreaded “tangent” discussed in the first chapter. The temptation to go off course can be very great because it is usually easier to write about yourself than to sustain the close attention a successful analysis requires. For instance, one of my students had a difficult time understanding Woody Allen’s film The Purple Rose of Cairo, so instead of challenging himself to think about it further, he decided to begin his paper this way: “In the film the main character behaves in a manner that is naïve. I too behaved naively once….” And the rest of the paper was about a trip he took to Las Vegas where he lost all the money he needed for college that semester. This might have been fine if he had chosen to write about this experience in the first place; however, he didn’t really analyze what happened to him during the trip either but simply reported on it. Too much attention to the significance leads to tangents, but ignoring it altogether makes the paper seem like a bland academic exercise with no lasting meaning.

Though you might think that it would be easier to discover the personal significance of something that you yourself are involved in, it can often be quite challenging, as anyone who has spent a sleepless night thinking about what a relationship or job means to them can testify. In fact, even something as simple as the trip to the gym that I wrote about in the previous chapter can lead to several complex insights:

So here I am, taking a break from working in front of the computer in order to go to a place where I am surrounded by even more machines, devices to work out on and devices to listen to as I go about it. I sometimes miss being a kid when I hardly relied on technology at all (I grew up before video games, iPods and the Internet). I would go out and play with other kids and we would create our own fantasies, games and exercises. I guess, however, that it is pretty unrealistic to assume that I would have the time to do that now, even if I could find friends my age that would be willing to take a break in the middle of the day. But maybe a change of setting wouldn’t hurt either. Perhaps I can go for a hike tomorrow instead of working out on the elliptical. It may take more time to get to my destination and be less efficient at burning calories, but I’m sure it will be a lot more fun.

None of these insights would have occurred to me if I hadn’t stopped to think about why I felt in such a rut every time I considered working out. I had to challenge myself to think beyond the obvious fact that exercise can sometimes feel like a chore to discover the more specific reasons I felt this way and what I could do to make it better.

The Broader Significance

When looking beyond the personal significance of your subject, you can examine a variety of related topics, depending on what you learned in the course of your analysis. However, the basic question you always need to ask is: how does your analysis offer a more complete and satisfying examination of your subject than those that have been done in the past, and how does this understanding lead to more appropriate insights about the discipline or situation from which your subject emerged? For instance, in his book The Ecology of Fear, environmentalist Mike Davis shows why it is important to reexamine the policies that have guided the city planning of Los Angeles for the past several decades:

For generations, market-driven urbanization has transgressed environmental common sense. Historic wildfire corridors have been turned into view-lot suburbs, wetland liquefactions zones into marinas, and floodplains into industrial districts and housing tracts. Monolithic public works have been substituted for regional planning and a responsible land ethic. As a result, Southern California has reaped flood, fire, and earthquake tragedies that were as avoidable, as unnatural as the beating of Rodney King and the ensuing explosion in the streets. In failing to conserve natural ecosystems it has squandered much of its charm and beauty.Mike Davis, Ecology of Fear (New York: Vintage Books, 1999), 9.

By revealing the disastrous consequences of basing city-planning decisions solely on short-term profits, Davis underscores the importance of his own, environmentally focused, analysis.

For Davis this perspective opens up an entire book outlining how Los Angeles (and by implication other cities) should use ecology, rather than short-term profit as the main guide for how it should develop. But sometimes the significance of your subject will seem so blatantly obvious that it feels like there just isn’t anything left to discuss. This does not necessarily mean that your focus is overly simplistic because many of the most powerful works gravitate toward very definitive points of view. Almost all critics agree that The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain is one of the greatest American novels and yet there is nothing subtle or ambiguous about how it shows slavery as an evil institution, particularly in one key scene. Huck, the narrator, has been helping Jim, a runaway slave, to escape. All his life Huck has been told that slaves are property and that anyone who helps a slave to escape is committing a deadly sin, one that will surely send him to Hell. Finally, Huck’s conscience gets the better of him and he writes a letter to Miss Watson, Jim’s “owner,” alerting her of their location. At first Huck claims, “I felt good and all washed clean of sin for the first time I had ever felt so in my life…” but on further reflection Huck begins to recall all the great things Jim had done for him, how he was the best friend that Huck had ever known, how he was much kinder to Huck than his own father. At that moment Huck sees the letter and makes his decision: “‘All right, then, I’ll go to hell’—and tore it up.”Mark Twain, The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn (New York: Norton, 2001), 344. Even if the point is obvious, that Jim is not just property, that slavery is an evil institution, and that Huck’s personal experience is a better guide for his conscience than a warped social morality, the emotional impact of this scene always brings a tear to my eyes.

Yet there are still ways to examine the significance of this scene that take us beyond the obvious: for instance, to discuss how people often distort religious maxims to justify profitable social conventions. Many people who lived at the time the novel takes place argued that slaves were property and The Bible commands us not to steal, and, therefore, helping a slave to escape is breaking one of the Ten Commandments. However, a closer reading of The Bible may lead us to see that the dignity of the individual should matter more than following rules that preserve an unjust social system. After all, Moses, the man who delivered the Ten Commandments in the first place, helped a whole country of slaves to escape. Along these lines we might also consider what issues we currently face that could potentially create conflicts between individual and social morality. Though all reasonable people should now agree that slavery was wrong, we can still speculate as to which actions, behaviors, or beliefs that we embrace today might seem repugnant to future generations.

Of course we can only speculate on future trends, but it isn’t necessary when exploring the significance to come to definitive conclusions. Just as your assertions on a given subject may express ambivalence, so might your discussion of what it implies. It is fine, even desirable, to express ambivalence as long as you do not do so in a vague manner. For example, if you were to consider a current issue that instigates a moral dilemma for you that’s similar to the conflict felt by Huck, you don’t want to simply sound confused: I guess we need to protect the environment, but I don’t know it seems like a hassle sometimes, though I guess I could do more, but I’m really busy right now and the bus is often late, so it’s easier to drive. Instead you might write: If people survive for the next hundred years, they may look back at our generation and shudder about how badly we treated the environment. I wish I could say that I am as dedicated as Huck in defying social convention, but I am just as guilty as most in choosing what is convenient over what is responsible. While the first sentence seems like the jumbled thoughts of one pondering the issue for the first time, the second reads like an intelligent consideration that acknowledges ambivalence.

If you still have trouble articulating what makes your subject significant, I suggest that you go back over the questions for initial consideration raised at the beginning of the last chapter. We are often driven to consider a particular subject because of the meaning it suggests to us, even when we have not yet fully grasped the implications of that meaning. This happens to me all the time. When I go to an art gallery or when I listen to an album, I will focus on a particular painting or song before I realize why it commands my attention. Only later when I’ve had time to really think about it, do I discover that it reminds me of something that happened in the past or helps me to clarify an issue that I’m currently pondering.

Though I’ve broken apart a way to consider analysis into particular elements to discuss each of them more clearly, when we actually begin to write on a subject, it will seldom follow such a neat and linear order. Instead our consideration of these aspects will take place recursively and sometimes in the reverse order of how I presented them, for when we think through the significance, we often come up with more precise assertions, which inspire us to choose more appropriate examples, which we can then explain more thoroughly. This takes time and effort but ultimately what we end up writing will be much more interesting than if we had simply jotted down the first thesis that came to mind and quickly tried to prove it. As we continue to think about our ideas, writing them down, considering them, modifying them, we eventually arrive at perspectives that are clear, reasonable, and worthwhile.

Exercise

Consider a cliché or aphorism that you often heard when you were a child. It could be something that your parents or teachers used to say to motivate you to work or to stop you from complaining. For example, I used to hear “life isn’t fair” to my frequent pointing out of familial injustices. Brainstorm or cluster on ways this cliché has been true in your life and on ways that it has been false or misleading. For example I might first make note of the inevitable injustices that come with living and then list ones that we have the ability to change. Try to fit your ideas into broader categories and then write a paragraph in which you more thoroughly examine the significance suggested by the cliché.

Key Takeaways

- A discussion of the significance of our interpretations can provide greater insight into our selves, our culture, and our core beliefs.

- Broad declarative statements and clichés should be avoided because they do not provide a satisfying exploration of why a particular perspective matters.

- Certain heuristics like brainstorming and clustering can help us to consider the broader implications of our subjects more thoroughly.

- A close examination of one aspect of analysis leads to a better understanding of the other areas as well.