This is “Foreign and National Security Policies”, chapter 17 from the book 21st Century American Government and Politics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 17 Foreign and National Security Policies

Preamble

On January 31, 2001, the US Commission on National Security/21st Century released its report warning that foreign terrorists would soon attack and kill many people in the United States.This account and the interviews appear in Stephen Hess and Marvin Kalb, eds., The Media and the War on Terrorism (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2003), 113–20. The commission was the brainchild of President Bill Clinton and Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, mandated by Congress, and chaired by two former senators, Warren Rudman (R-NH), and Gary Hart (D-CO). It spent $10 million and worked for three and a half years. To ensure widespread coverage of the report, its chairmen hired a public relations firm, visited newspapers’ news bureaus in New York and Washington, DC, briefed key members of Congress, and unveiled it at a news conference on Capitol Hill.

The report was not entirely ignored but never received the media attention it warranted. The wire services reported it, as did the Washington Post>, the Los Angeles Times, and CNN. USA Today published a short piece on the report. But there were few stories in the rest of the news media when the commission reported or later. Nothing about it was reported in the New York Times. Most Americans were unaware of the report and of the deadly danger it warned of.

Interviewed a year later, journalists regretted the limited coverage. They attributed it to various factors. One was timing: the press covers only a few major stories at any time and the cut in interest rates and the electricity crisis in California were deemed more newsworthy because of their immediate effects on people. The apparent lack of interest from public officials was another explanation. The news media would have covered the report far more if President Clinton, who had just left office, had promoted it or if his recently inaugurated successor George W. Bush had held a news conference about it or invited the two senators to the White House or had highlighted terrorism in a speech. President Bush did none of these things. Nor did Congress hold a hearing on the report or make terrorism a priority. The report also lacked immediacy: it was a prediction about an event that might happen.

The media failed to connect the report to past events: terrorists had previously staged several attacks against the United States, including destroying two US embassies and damaging the World Trade Center. “In the three months leading up to 9/11, the phrase Al Qaeda was never mentioned on any of the three evening news broadcasts—not once.”Tom Fenton, Bad News (New York: Regan Books, 2005), 4.

This case shows that not reporting or insufficiently reporting stories can be significant. The news media put no pressure on President George W. Bush to take action to try to forestall terrorist attacks. They denied people information and understanding about the terrorist threat and limited their ability to hold the administration accountable for a policy failure when the attacks occurred. After the attacks, they arguably gave excessive and positive coverage to the Bush administration’s responses to terrorists and terrorism.

Enduring Image

The Twin Towers

On 9/11 Al Qaeda terrorists armed with simple box cutters took over four passenger planes, transforming them into lethal weapons. They flew two of the jets into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, killing 2,823 people from around the world and injuring many others. They flew the third jet into the Pentagon, causing more casualties and serious damage to the building. Passengers prevented the terrorists from flying the fourth plane to Washington, DC, and the plane crashed in the Pennsylvania countryside. Shown throughout the world, the horrifying shots of the planes flying into the Twin Towers and of the towers’ destroyed remnants are enduring images of a spectacular attack on the symbols of US economic might. They graphically exposed the ability of terrorists from abroad to attack on US soil. They shocked Americans into realizing their country’s vulnerability, with its six thousand miles of land borders and three hundred ports of entry.

Clear Shot of Plane Hitting Tower Two

To a nation accustomed to Hollywood disaster blockbusters, the 9/11 attack was harsh reality.See Anthony Lane, “This Is Not a Movie,” New Yorker, September 24, 2001, 79. Yet the phrases used by television commentators had an eerie familiarity: they recalled Hollywood’s fictional movie The Siege, a 1998 thriller about terrorists attacking targets in New York City.

President Bush and other US government and military leaders responded to the attacks depicted in the devastating images and words of the media. Their themes were American national identity, strength, and power. Their purpose was to unite the American public and mobilize support for a “war on terrorism” to be waged abroad and at home. In their stories, journalists repeated and thereby reinforced these themes and supported the purposes.John Hutcheson, David Domke, Andre Billeaudeaux, and Philip Garland, “U.S. National Identity, Political Elites, and a Patriotic Press Following 9/11,” Political Communication 21, no. 1 (January–March 2004): 27–50.

The United States is the global superpower and world leader. It operates in a world beset by famine, poverty, disease, and catastrophes both natural (tsunamis, earthquakes) and man-made (climate change, pollution of the seas and skies, and release of radioactive materials from nuclear plants). It is a world of genocide, regional and ethnic strife, and refugees. Terrorism, conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the nuclear weapons programs of Iran and North Korea, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (“loose nukes”), the Arab-Israeli conflict, and instability and challenges to autocratic rulers in the Middle East are only the most obvious of the foreign policy issues that affect the United States. Others are economic upheavals, the rise of China to world economic and political power, relations with Russia, AIDS in Africa, dependence on oil from undemocratic states, the importation of illegal drugs, and the annual US trade deficit of around $800 billion.

At the same time, the United States is extraordinarily active, often militarily, in international affairs. Since 1989, it has intervened in Panama, Kuwait, Somalia, Bosnia, Haiti, Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq.On the justifications for war since 1990, see Nicholas Kerton-Johnson, Justifying America’s Wars: The Conduct and Practice of US Military Intervention (New York: Routledge, 2010). On the other hand, it stood aside as hundreds of thousands of people were killed in the Rwandan genocide. President Clinton later apologized for doing nothing in Rwanda.

America’s military expenditures are enormous. The annual defense budget is around $711 billion plus more billions for Homeland Security. That’s about ten times greater than any other nation. The United States has around eighty major weapons programs under development with a collective price tag of $1.3 trillion. It has formal or informal agreements to defend thirty-seven countries. It has more than 700 military installations abroad in approximately 130 countries, including South Korea, Germany, and dictatorships such as Uzbekistan. Excluding Iraq and Afghanistan, some 200,000 American military personnel plus a roughly equal number of dependents and civilians are stationed abroad. The United States is the world’s leading supplier of weapons to the rest of the world.

Link

US Department of Defense Budget

View the defense budget at http://comptroller.defense.gov/budget.html.

According to an investigation by the Washington Post, the government responding to the terrorist attacks of 9/11 has created a top-secret America:

- “1,271 government organizations and 1,931 private companies work on programs related to counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence in about 10,000 locations across the United States.”

- “An estimated 854,000 people…hold top-secret security clearances.”

- “Many security and intelligence agencies do the same work.…For example, 51 federal organizations and military commands…track the flow of money to and from terrorist networks.”Dana Priest and William M. Arkin, “Top Secret America,” Washington Post, July 19, 2010, 1ff.

This chapter explains why the United States has become so involved in the world, how the government is organized to make foreign and national security policies, and the most important policies that result.

17.1 The Executive Branch Makes Foreign and Military Policies

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- Who is involved in making foreign policy?

- How do the president and the bureaucracy interact in constructing foreign policy?

- What are some of the causes of competition or disagreement among makers of foreign policy?

Foreign policy is made by the president, presidential advisors, and foreign policy bureaucracies.

The President

Formal powers specified in the Constitution put the president at the center of foreign policy. They include being commander in chief of the armed forces, negotiating treaties, and appointing ambassadors. The president is also the spokesperson for and to the nation: notable presidential addresses have been made by Franklin D. Roosevelt after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 and by George W. Bush following the 9/11 attacks.

How presidents manage the bureaucracy influences the information they receive and their range of policy options.Gary R. Hess, Presidential Decisions for War: Korea, Vietnam, and the Persian Gulf. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001). Franklin Roosevelt opted for overlapping jurisdictions, with departments competing for influence and his attention. Other presidents established rules and procedures for processing information and vetting opinions. President Clinton sought out independent-minded advisors and gave them some leeway to decide policy. President George W. Bush relied on a few advisors, particularly Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld.Thomas Preston and Margaret G. Hermann, “Presidential Leadership Style and the Foreign Policy Advisory Process,” in The Domestic Sources of American Foreign Policy, 4th ed., ed. Eugene R. Wittkopf and James M. McCormick (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), 363–80.

National Security Advisor

Foremost among the president’s foreign policy advisors is the national security advisorLeading advisor to the president on national security and foreign policy.. Issues the advisor faces include how to serve and protect the president’s interests and how to deal with other makers of foreign and defense policy in the government.

Some national security advisors have built a large staff to help them formulate options and oversee policy implementation. They have been vocal in espousing and expressing their views. One of the most powerful and forceful national security advisors was Henry Kissinger, who served President Richard Nixon. He understood the job as requiring him to interact frequently with the media to communicate his and the president’s policy views. He was famously successful in dealing with reporters, especially the three television networks’ correspondents and the influential Washington columnists specializing in foreign affairs. He was able to “disarm them with his wit, intimidate them with his brilliance, flatter them with his confidences and charm them with his attention.”Walter Isaacson, “The Senior Official,” Washington Journalism Review 14, no. 9 (November 1992): 30; see also Walter Isaacson, Kissinger (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992). His critics were likely to be telephoned, cajoled, stroked, invited to dine, and visited at their homes.

The national security advisor is often in competition with the secretary of state. In the starkest example, President Jimmy Carter’s national security advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, clashed frequently with Secretary of State Cyrus Vance. He tried to manage policy in the White House and did not always communicate decisions to other policymakers. Vance resigned in protest over not being informed in advance about the attempt to rescue the American embassy personnel held hostage in Iran in 1980.

Some national security advisors try to be neutral facilitators in policy debates between the heads of the major foreign policy bureaucracies. They are not always successful. President Ronald Reagan’s national security advisors were unable to mediate between the constantly warring Secretary of State George Shultz and Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger or control Director of Central Intelligence William Casey.

The trend in recent administrations has been to select knowledgeable and low-key individuals who can provide the president with expert advice but not invite or engage in running conflicts with the other foreign policy bureaucracies. Sometimes this turns into catering to the president’s wishes, as Condoleezza Rice did with President George W. Bush’s wish to go to war with Iraq. After his reelection in 2004, he appointed her secretary of state.

Led by the national security advisor, the National Security Council’s Principals Committee consists of the president’s senior security advisors, relevant cabinet members, and military and intelligence advisors. The president’s principal forum for considering national security and foreign policies, it is supposed to ensure consensus on and coordinate the policies among the various government agencies. But it is not easy to avoid internecine warfare among its participants, and discourage (let alone prevent) the secretaries of defense and state and the vice president, as well as special envoys to trouble spots, from communicating to the president unilaterally to influence and make policy.

The State Department

The State Department is the oldest cabinet-level department. It has primary responsibility for managing the foreign affairs budget and resources, leading and coordinating other US agencies in developing and implementing foreign policy, leading and coordinating US representation abroad, and negotiating with foreign countries.

In none of these areas is its leadership unchallenged. Within the United States, the national security advisor has often eclipsed the secretary of state and the State Department as the principal source of policy ideas. The Defense Department has long been a competitor in national security policy and the US Special Trade Representative provides an alternative source of economic advice for the president. Abroad, the ambassador’s authority in the US embassy is often resisted by personnel assigned to it by other agencies, such as those responsible for spying.

The State Department’s lead position in foreign affairs has also been compromised by congressional reluctance to pass foreign affairs appropriations, restrictions it imposes on how the funds can be spent, and micromanaging of the foreign affairs budget.

Congress also requires the State Department annually to certify countries as meeting targets on human rights, arms control, reducing drug trafficking, and other areas in order to remain eligible for foreign aid. An escape hatch does allow presidents to certify a country for aid if it is in the “national interest” to do so.

Defense Department

For most of its history, the military was organized under separate commands of the War Department and Navy Department. No political or military authority other than the president existed above these departments to coordinate and direct them. This changed after World War II, when the 1947 National Security Act established the cabinet-rank position of the secretary of defense. In 1949, an amendment to the 1947 National Security Act established the Defense Department and the post of chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff .

Exercising command authority over the military on behalf of the president, the secretary of defense participates in making and executing foreign policy, especially when it requires the use of force. Thus Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was intimately involved in the decision to attack Iraq in 2002 and was responsible for the execution of the policy.

The chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff plans and coordinates the deployment of American forces, the unified commands conduct these operations, and the military services train and equip the necessary forces. Since the 1980s, a dominant issue within the Defense Department has been improving the operational efficiency of the armed forces.Eliot A. Cohen, “A Revolution in Warfare,” Foreign Affairs 75 (1996): 37–54; and Thomas G. Mahnken and James R. FitzSimonds, “Revolutionary Ambivalence,” International Security 28 (2003): 112–48. The concern for operational efficiency is joined by a concern for cost. Almost half of the Defense Department’s annual budget goes to salaries and a quarter to operating and maintaining military forces.

The twin concerns for efficiency and cost have been combined in three debates over the ability of the United States to fight wars today. One debate is between defense hawks, who want increased defense spending to ensure US security, and deficit hawks, who wish to reduce all areas of government spending. A second debate is over military readiness. Does the military consist of “hollow forces” that look robust on paper but lack training, modern weapons, and effectiveness? The third debate is over the impact of modern technology on how the United States organizes, prepares for, and fights wars.

All three debates took place over the Iraq War. Deficit hawks reacted with great concern to the Bush administration’s continuously rising price tag for the war and the occupation and reconstruction of Iraq. The second debate was seen in the concerns expressed by National Guard units over the length of time they were serving in Iraq and the refusal of the military to allow many career soldiers to leave, resign, or retire. The debate over the role of technology in warfare was central to the dispute between Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and many senior military officers over how to conduct the war and how large a military force was necessary.

The Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was created by the National Security Act of 1947. Its main task was to correlate, evaluate, and disseminate intelligence.John Ranelagh, The Agency: The Rise and Decline of the CIA (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986); and Arthur S. Hulnick, Fixing the Spy Machine: Preparing American Intelligence for the Twenty-First Century (Westport, CT: Praeger,1999). It was not explicitly authorized to engage in covert action or to collect its own information. Both of these tasks, however, quickly became part of its mission.

The CIA’s directorate for operations engages in covert operations. By the 1970s, the cumulative effect of two decades of covert action and of news stories about them produced a media and thus public image of the CIA as a “rogue elephant” that was out of control. Congress then created two special committees, one in each chamber, to oversee intelligence. It also insisted that covert actions be accompanied by an explicit “Presidential Finding” that the cover actions are in the national interest.

Other Intelligence Agencies

The CIA is one of several intelligence agencies. Others are

- the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research;

- the agencies of the military services;

- the Defense Department’s National Security Agency (NSA), which is charged with maintaining the security of US message traffic and intercepting, analyzing, and cryptanalyzing the messages of other states;

- the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA);

- the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI);

- the Department of Homeland Security.

They operate independently of the CIA.

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the CIA’s intelligence estimating abilities and procedures came into question. Of concern was the absence of clandestine collection capabilities (spies) in many parts of the world that harbor anti-American terrorist movements or possess weapons of mass destruction. Also questioned was the CIA’s lack of cooperation with the FBI and other intelligence agencies. Perhaps most devastating was the finding of the 9/11 Commission that investigated the terrorist attacks: “a failure of imagination” kept the intelligence agencies from anticipating and thwarting the attacks.

Link

The 9/11 Commission

Read the findings of the 9/11 Commission at http://www.9/11commission.gov/.

The Iraq War brought forward new charges of intelligence failures. At issue here was the quality of the intelligence that contributed to the decision to go to war and the failure to find evidence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. Their supposed existence and the imminent threat posed by them to the United States had figured heavily in President Bush’s justification to Congress and the American people for the war.

Director of National Intelligence

In response to intelligence failures, Congress passed and President Bush signed legislation creating a Director of National Intelligence (DNI) in December 2004; the DNI was to be the president’s chief intelligence advisor, with substantial control over the government’s intelligence budget of approximately $40 billion. The DNI would be the overall leader of fifteen independent and rival agencies. The CIA director now reports to the DNI. In practice, the power of the intelligence job depends on the director’s relationship with the president.

Department of Homeland Security

This newest part of the foreign policy bureaucracy was conceived in response to the 9/11 attacks and became effective in November 2002.Glenn P. Hastedt, “Homeland Security,” in Contemporary Cases in U.S. Foreign Policy: From Terrorism to Trade, 2nd ed., ed. Ralph G. Carter (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2005); Harold Relyea, “Organizing for Homeland Security,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 33 (2003): 602–24.

The Department of Homeland Security combines activities from 22 different federal agencies with a total workforce of 170,000 employees. Agencies incorporated in the department include the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), the Secret Service, the Customs Service, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Transportation Security Administration, the Coast Guard, and the Border Patrol. Some observers are concerned that the combination of foreign policy and domestic missions in the same department limits its effectiveness. That is, the capacities to meet the challenges posed by earthquakes, floods, blackouts, and storms (tasks that are central to FEMA’s mission) have been underdeveloped as more resources and attention are given to fighting terrorism or that the need to respond to these catastrophes will divert attention away from fighting terrorism.

The US Trade Representative (USTR)

This is the title given to both an agency located within the Executive Office of the President and to the individual who heads the agency.Steven Dryden, Trade Warriors (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995).

Congress created the office in 1962 largely out of frustration with the State Department’s handling of international trade. It felt that the State Department was too concerned with the policy positions of foreign states and was not responsive enough to American business interests. The USTR is responsible for developing and coordinating US international trade policy. This includes all matters that fall within the jurisdiction of the World Trade Organization, which establishes the rules of trade between states.

Key Takeaways

Foreign and military policies are made and carried out by the executive branch, particularly the president, with the national security advisor, the State Department, the Defense Department, the Department of Homeland Security, and the intelligence agencies. The National Security Act of 1947 and recent bureaucratic reorganization after 9/11 reshaped the structure of foreign policymaking. Parties involved in making foreign policy often disagree over policies, military spending and military goals, and much more.

Exercises

- What formal powers put the president at the center of foreign policy? How might being the head of the executive branch give the president an informal advantage in making foreign policy?

- How did the National Security Act reorganize the national security establishment? What do you think the idea behind the National Security Act was?

- What are the responsibilities of the Department of Homeland Security? Do you think it makes sense to have one department handle all those jobs? Why or why not?

17.2 Influence from Congress and Outside Government

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How does Congress influence foreign policy?

- How have presidents attempted to deal with congressional involvement in international affairs?

- What nongovernmental groups influence foreign policy and how?

The constitutional division of power between the president and Congress is an “invitation to struggle over the privilege of directing U.S. foreign policy.”Louis Henkin, Foreign Affairs and the Constitution (Mineola, NY: Foundation Press, 1972), 131; and Lee Hamilton, A Creative Tension: The Foreign Policy Roles of the President and Congress (Washington DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2002). This struggle is most likely to take place when different political parties control the presidency and Congress, when powerful members of Congress disagree with the administration’s policies, and when these policies are controversial or unpopular.

The president’s ability on occasion to make decisions and take action quickly gives him more power over foreign policy than Congress, which takes more time. Nonetheless, Congress can be influential by asserting its amending, oversight, and budgetary powers.

By attaching amendments to pieces of legislation, Congress has directed foreign aid funding for specific countries or purposes such as aid for Israel, buying products made in America, and prohibiting money from being spent on family planning programs.Ruth Berins Collier, “Foreign Policy by Reporting Requirements,” Washington Quarterly 11 (1988): 74–84. But amendments are normally limited to relatively minor policies.

Congress can also exercise influence through oversight of the executive branch’s implementation of foreign or military policy.Loch K. Johnson, “The U.S. Congress and the CIA: Monitoring the Dark Side of Government,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 4 (1980): 477–99. During the Vietnam War, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, chaired by Senator J. W. Fulbright (D-AR), held hearings critical of the administration’s conduct of the war. During the George W. Bush administration, committees in the House and Senate held hearings on the abusive treatment of prisoners by US soldiers at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq and what higher-ups in the command knew about them. But hearings usually take place after policies have been implemented or too late to change them significantly.

Congress can also influence foreign policy through its budgetary powers. It can reduce or even refuse to fund programs. But congressional budgetary powers are blunt and not fine-tuned to the particulars of a policy. Cutting off funding is particularly difficult when it makes members vulnerable to accusations (especially in campaign advertisements directed against them by their opponent) of failing to fund the troops, as happened during the Iraq War. Budgetary controls also do little to offset the president’s authority to commit the United States to a course of action by announcing such policy decisions as a war on terrorism.

The struggle between Congress and the president to control American foreign and military policy can also take place over three constitutional powers that the president and Congress share: appointments, treaties, and war.

Appointments

The president appoints, but the Senate has the constitutional authority to approve the appointment of ambassadors and those charged with running government departments that conduct foreign policy, such as the Departments of State and Defense. This gives the Senate a voice in how these organizations are run. The Senate does readily and routinely confirm most appointees, but this is often because the president, anticipating objections, usually makes unobjectionable appointments.

In addition, presidents often evade the appointment problem by using people whose appointment is not subject to Senate approval as negotiators. These people may be trusted allies of the president or have expertise in the issue being negotiated. In the Reagan administration, National Security Council staffer Lt. Col. Oliver North was the driving force in the ill-fated Iran-Contra deal that would have freed the American hostages in Iran and funded the Contras in Nicaragua through secret weapons sales to Iran.

Link

Oliver North

Read a related interview with Oliver North online at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/drugs/special/north.html.

Treaties

The Constitution states that it is the president who by and with the advice and consent of the Senate negotiates treaties. The approval of two-thirds of the senators voting is required. The Senate does not always consent. The Republican-controlled Senate, for example, rejected the Treaty of Versailles negotiated by Democratic President Woodrow Wilson following the end of World War I. This treaty created the League of Nations, the forerunner to the United Nations, but with the treaty’s rejection the United States did not join. Today, presidents routinely include key members of the Senate on negotiating teams as a means of obtaining advice before and easing consent after a treaty is signed.

The Senate has rejected few treaties outright, but presidents have learned that approval is not assured even when senators are involved or at least consulted in advance.Loch K. Johnson, The Making of International Agreements: Congress Confronts the Executive (New York: New York University Press, 1984). For example, in 1999 the Senate rejected, by a vote of fifty-one to forty-eight, the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which would have banned all tests of nuclear weapons.Stephen I. Schwartz, “Outmaneuvered, Out Gunned, and Out of View,” The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 56 (January 2000): 24–31. Even without rejecting a treaty, the Senate may modify it by making amendments and thereby undermining a complex international agreement and bringing about a diplomatic or security crisis.

The Senate’s power of advice and consentConstitutional authority of the Senate to approve treaties—approval from two-thirds of the senators voting is required. is somewhat negated by the president’s increased reliance on executive agreements over treaties as a means of entering into agreements with other states.Lawrence W. Margolis, Executive Agreements and Presidential Power in Foreign Policy (New York: Praeger, 1986). Unlike treaties, executive agreementsAgreements that the president enters into with other states; unlike treaties, they do not require the consent of the Senate before becoming law. do not require the consent of the Senate before becoming law. Presidents are free to enter into them at their own discretion and to end them when they see fit. Congress has tried to curb this power but with little effect. In the 1970s, it passed the Case-Zablocki Act that required presidents to inform Congress of any and all executive agreements they entered into.

War Powers

The Constitution grants Congress the power to declare war and to raise and maintain armed forces. But when does a state of war come into existence? The United States has sent troops into battle over 125 times in its history, yet Congress has declared war only five times: the War of 1812, the Spanish-American War, the Mexican War, World War I, and World War II. No declaration of war preceded the entry of American forces into the Korean War. President Harry Truman all but ignored Congress, basing his use of force on a UN Security Council resolution, an argument that would be used again later in the Persian Gulf War and the Iraq War. Vietnam too was fought without a declaration of war. When the legality of this war was challenged, defenders pointed to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, in which Congress authorized the president to take whatever steps he felt necessary to protect and defend American forces in South Vietnam; the war’s defenders also pointed to congressional votes authorizing funds for fighting the war. The argument was that if Congress did not support the war, all it had to do was stop authorizing funds to fight it. Such an action is far easier said than done.

The congressional–presidential struggle over war-making powers came to a head during the Vietnam era and led to Congress passing the War Powers Resolution over President Richard Nixon’s veto. This resolution effectively allows the president ninety days to wage war without congressional approval. No president has recognized the constitutionality of the War Powers Resolution, though none has openly challenged it either. (See Chapter 13 "The Presidency".)See William G. Howell and Jon C. Pevehouse, While Dangers Gather: Congressional Checks on Presidential War Powers (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007).

Influence from Outside Government

Influence can be exerted on foreign and national security policy by think tanks, interest groups, and the public through opinion polls and elections.

Think Tanks

Think tanks are private research organizations that seek to influence public policy. They have been referred to as “idea brokers” because they help define the issues on the policy agenda and options for addressing them.Donald E. Abelson, Think Tanks and Their Role in U.S. Foreign Policy (New York: St. Martins, 1996).

Foreign policy is an area in which think tanks have become especially active for several reasons. First, it has become much more complex: no longer restricted to national security, foreign policy encompasses trade, finance, human rights, the environment, and cultural issues. Second, the information abilities of the government have been overwhelmed by this expanded foreign policy agenda. Long-range planning and strategic speculation are now commonly produced by think tanks, as is current information on breaking issues. Third, think tanks provide multiple and competing policy recommendations backed up with supporting information.

Interest Groups

A wide variety of groups try to influence US foreign policy. There are economic groups such as the Chamber of Commerce and the American Farm Bureau Federation. There are ethnic groups representing Arab, Greek, Turkish, Chinese, Cuban, and Eastern European Americans.Tony Smith, Foreign Attachments: The Power of Ethnic Groups in the Making of American Foreign Policy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000); and Alexander DeConde, Ethnicity, Race, and American Foreign Policy (Boston: Little Brown. 1992). Ideological and public interest groups seek to influence US foreign policy in such areas as human rights (Amnesty International) and the environment (the Sierra Club).

As documented in Chapter 9 "Interest Groups", foreign governments can also behave as interest groups. After 9/11 and during the Iraq War, Saudi Arabia came under harsh criticism in the United States for its failure to crack down on terrorist groups. Part of the Saudi response was to engage in a large-scale media and lobbying campaign to improve its image and relations with government in the United States.

Interest groups often conflict on an issue. In the debate over creating free trade areas such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), business groups were pitted against labor and environmental groups. In other cases, one interest group seems to dominate a policy area. This has long been the case with the Arab-Israeli conflict, where Jewish-American groups, notably the American-Israeli Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), have been particularly influential.

Public Opinion

Americans have “limited attention and low levels of knowledge about the details of foreign affairs.”Benjamin I. Page with Marshall M. Bouton, The Foreign Policy Disconnect: What Americans Want from Our Leaders but Don’t Get (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 226. Nonetheless, they have views about foreign policy. These are influenced by the opinions of trusted elites as communicated, not always accurately, by the media.Matthew A. Baum and Tim J. Groeling, War Stories: The Causes and Consequences of Public Views of War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010).

More generally, Americans would like their country to pursue national security and international justice through participation in treaties and agreements and collective decision making within international organizations. They would also like the country to combat international terrorism, prevent the spread of nuclear weapons, reduce levels of immigration, and protect Americans’ jobs.

Many of these opinions are neither detailed nor intensely held. The public therefore usually goes along with America’s foreign policies or at least gives policymakers the benefit of the doubt unless the media tell them that things have gone wrong. Nonetheless, the public can sometimes initiate and constrain foreign policy.Andrew Johnstone and Helen Laville, eds., The US Public and American Foreign Policy (New York: Routledge, 2010).

The timing of elections is one way public opinion influences the president’s willingness to undertake foreign policy initiatives and exercise military force. Presidents become increasingly hesitant to take foreign policy risks as elections approach for fear of having their leadership called into question. Even successes can be criticized as being too costly. So deep-seated is this reluctance to act that a common complaint from foreign leaders is that US foreign policymaking grinds to a halt every four years. For a different view, there is the film Wag the Dog (1997), in which a president’s aides invent a war with Albania to distract media and public attention from his involvement in a sex scandal that is about to derail his reelection.

One question that has received considerable attention is the American public’s opinions about the use of military force. The conventional wisdom after Vietnam was that Americans would not support military action if it resulted in significant casualties to US troops. This was called the Vietnam syndromePost-Vietnam assumption by US policymakers that Americans would not support military action if it resulted in significant casualties to US troops..

As a result, any military involvement in the future would have to be short and involve the overwhelming application of force.Bruce W. Jentleson, “The Pretty Prudent Public: Post Vietnam Public Opinion on the Use of Military Force,” International Studies Quarterly 36 (1990): 49–74. The George W. Bush administration’s decision to minimize the number of US forces on the ground in the Iraq War and the heavy use of air power as a prelude to the ground war reflected this syndrome.

The American public’s willingness to tolerate casualties depends on the reasons for military action.Peter D. Feaver and Christopher Gelpi, Choosing Your Battles: American Civil-Military Relations and the Use of Force (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004). People are most supportive of the use of military force when they believe it is to protect the United States against attack. Nonetheless, protracted conflicts lower presidential popularity: witness Korea and President Truman, Vietnam and President Johnson, and Iraq and President George W. Bush.

Key Takeaways

Congress is involved in foreign and military policies through its amending, oversight, and budgetary powers and through the constitutional power related to appointments, treaties, and war it shares with the president. While Congress has sometimes worked to limit the president’s autonomy in foreign policy, the use of executive orders and the ability to enter military engagements without formal declarations of war have ensured the president’s continued primacy in international affairs. Forces that sometimes influence foreign and military policies from outside government are think tanks, interest groups, and public opinion.

Exercises

- What formal constitutional powers does Congress have that allow it to influence foreign policy?

- Why might it be difficult for Congress to limit the president’s power to send troops into combat, even though it is Congress that has the formal power to declare war?

- Why do you think the American public is relatively uninterested in foreign affairs? What foreign policy issues do you think Americans care about the most?

17.3 The Major Foreign and National Security Policies

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What are isolationism and internationalism? How have they been incorporated into US foreign policy?

- How did World War II change the direction of US international involvement?

- What policies guided US action during the Cold War and the Vietnam War?

In this section we move from the makers of US foreign and national security policies to the policies they have made.

From Isolationism to Internationalism

Two visions have competed for how the United States should orient itself to world politics. They are isolationism and internationalism. IsolationismBelief that US national interests are best served by avoiding involvement with foreign countries., the policy of trying to stay aloof from foreign entanglements, has long roots in American foreign policy.Selig Adler, The Isolationist Impulse (New York: Praeger, 1957). Many date it back to George Washington’s Farewell Address, which warned Americans to “steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.”

During the period between World War I and World War II, the United States pursued a largely isolationist foreign policy. It refused to join the League of Nations, and Congress passed a series of bills in the 1930s that imposed a policy of neutrality on the United States in foreign conflicts.

Isolationism ended with US involvement in World War II. It may regain some favor now as Americans react negatively to the financial and human cost of involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan. Media stories about outsourcing, in which American companies give the jobs of their American employees to low-paid workers overseas, may add to the isolationist impulse.

Meanwhile, internationalism reigns. InternationalismBelief that US national interests are best served by involvement with foreign countries. means involvement in events beyond one’s borders to accomplish and protect the national interest.David A. Baldwin, ed., Neorealism and Neoidealism: The Contemporary Debate (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993); and Joseph S. Nye Jr., The Paradox of American Power (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002). It has dominated American foreign policy since 1955, a decade after World War II ended. Internationalists favor democratization, free trade, and a policy of global military activism designed to maintain America’s dominant position in world affairs. But specific policies have varied depending on the administration in power.

We discuss the most important of these policies: containment, deterrence, détente and arms control, and the use of military force by the United States, particularly in Vietnam and Iraq.

Containment

The World War II alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union soon gave way to a series of international crises that divided the victors into two opposing blocs. The result was a Cold WarThe rivalry and consequent arms race between the United States and its allies and the Soviet Union and its allies, which lasted from the end of World War II until the late 1980s. of the United States and its allies against the Soviet Union and other Communist countries.

The concept guiding American foreign policy in this global struggle with the Soviet Union and its allies was containmentThe US policy of vigilance and alliances to prevent the spread of Communism..John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Containment (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993). It held that the United States did not need to engage in a war to defeat the Soviet Union. Instead it could adopt a policy of constant vigilance and the creation of alliances in which American power would be used to contain and counter Soviet aggressive moves.

Link

Containment Strategy

Read about containment strategy at http://www.nuclearfiles.org/menu/key-issues/nuclear-weapons/history/cold-war/strategy/strategy-containment.htm.

During the Cold War, the news media focused on the conflict between the United States and Communist countries. The main stories were the Communist takeover of China, the Korean War, US relations with Cuba, and the Vietnam War. Thus until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the US media depicted the world in general and the preceding stories in particular from the American side of the Cold War frame.

Deterrence

Another concept guiding US foreign and military policy during the Cold War was deterrenceThe assumption that US possession of nuclear weapons would hold the Soviet Union in check by threatening it with destruction should it engage in nuclear aggression..Patrick M. Morgan, Deterrence: A Conceptual Analysis (Beverly Hills: Sage, 1977). According to deterrence theory, nuclear weapons were too powerful and destructive to be used as instruments of warfare. They were best suited to holding an opponent (here, the Soviet Union) in check by threatening it with destruction should it engage in an act of nuclear aggression.

Deterrence strategies are designed to prevent an opponent from undertaking an objectionable course of action. It was an article of faith during the Cold War that nuclear deterrence could not be assumed to exist through the possession of a large nuclear arsenal. The United States adopted a second strike strategy: to deter an attack by possessing the capability to absorb an enemy’s nuclear attack and retaliate with so much force that it could inflict an unacceptable level of damage on its society. Stability was assumed to be assured when both sides adopted such a strategy.

Link

Deterrence Strategy

Read about deterrence strategy at http://americanhistory.si.edu/subs/history/timeline/different/nuclear_ deterrence.html.

This created a situation of mutual assured destructionDeterrence by being able to absorb a nuclear attack and have enough nuclear weapons left over to inflict an unacceptable level of damage on the enemy.. Thus a major concern of policymakers in the United States was that the Soviet Union not be allowed to gain a significant advantage over the United States in the size of its nuclear inventory. Because Soviet leaders shared the same goal, the result was an arms race.

Vietnam

As the Cold War expanded in the late 1950s and early 1960s, containment entered the third world. Already the United States had helped bring down anti-American governments in Guatemala and Indonesia. Now newly independent states in Africa and Asia became political and military battlegrounds in which the United States and Soviet Union supported competing local leaders.

The most enduring and significant extension of containment to the third world came in Vietnam.Robert L. Gallucci, Neither Peace nor Honor (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975); and Leslie H. Gelb with Richard K. Betts, The Irony of Vietnam: The System Worked (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1979). The Geneva Peace Accords envisioned a country temporarily divided at the seventeenth parallel with Communist forces in control of North Vietnam and pro-Western forces in control of South Vietnam. But North Vietnam and its Communist allies in South Vietnam began a military campaign to unify all of Vietnam.

US Involvement in Vietnam

When President Dwight Eisenhower left office, the United States had one thousand military advisors in South Vietnam. President John F. Kennedy authorized an additional fifteen thousand advisors. Under President Lyndon Johnson, the war became increasingly Americanized as US forces carried out sustained and massive bombing campaigns against the North and US ground troops began fighting in the South.

The Tet Offensive

A turning point in the war came in late January 1968. Seeking a final, decisive victory, the Communists launched a massive simultaneous attack, known as the Tet Offensive, on major cities throughout the country. In the attack on Saigon, the South Vietnamese capital, soldiers temporarily invaded the American embassy grounds, in full view of American reporters and television news crews.

From a purely military standpoint, Tet was a disaster. Nearly two-thirds of the Communist troops were killed or captured. The expected popular uprising against the Americans and South Vietnamese government did not take place.

Media Response to Tet

Yet by the end of the Tet Offensive, significant segments of the media and thus the American public had turned against the administration’s conduct of the war, if not the war itself. In February 1968, the Wall Street Journal warned readers in an editorial that the effort in Vietnam may be “doomed.” Following a visit to Vietnam, CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite famously declared that “it is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy and did the best they could.” And a special report on NBC television declared the war a failure.Editorial, Wall Street Journal, February 23, 1968, 14; CBS News Special: Report From Vietnam, February 27, 1968; and NBC News Special Report, March 10, 1968.

Even before Tet, media coverage of the war was becoming more critical. The media’s response was driven by a cumulative reaction to the “credibility gap” that had existed for many months between the optimistic statements of the administration and the military command and the experiences of reporters and soldiers in the field. This critical reporting was indexed to growing dissent within the Johnson administration and the Democratic party, evidenced by Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy seeking the presidential nomination on an antiwar platform. It was also represented and reinforced by images capturing the brutality and horror of the war.

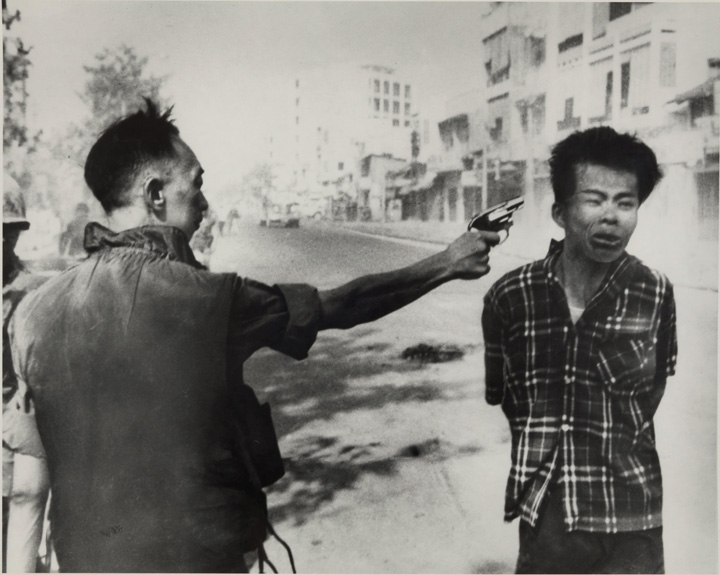

Figure 17.1

The director of South Vietnam’s national police force executes a bound Viet Cong prisoner.

The photograph and television footage of the execution by the director of South Vietnam’s national police force of a Viet Cong prisoner on the streets of Saigon during the Tet Offensive helped galvanize US opposition to the Vietnam War.

Source: Photo by Eddie Adams, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2009632258/.

Link

A photo of a naked Vietnamese girl and other children fleeing napalm challenged the justification for the US involvement in Vietnam by graphically exposing the cruelty of the war on innocent children. See the legendary image at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:TrangBang.jpg.

By late March, approval of President Johnson’s “handling of the situation in Vietnam” had dropped to 26 percent and disapproval swelled to 63 percent.Gallup Organization, Vietnam War: A Compilation, 1964–1990. Public Opinion and the Vietnam War: National and International Opinion, vol. II (Princeton, NJ: Gallup, 1992). On March 31, 1968, the president announced he would not run for reelection and that US bombing of North Vietnam would be restricted.

After he took office in 1969, President Richard Nixon pursued a policy of Vietnamization. It was designed to create conditions so that by 1972 the South Vietnamese army would be able to hold its own when supported by US air and sea power. Congress held hearings and cut off some funds. There were demonstrations against the war, especially on college campuses. Nixon’s strategy failed, and in spring 1972 North Vietnam attacked South Vietnam, forcing Nixon to re-Americanize the war. By the time the war finally ended, 55,000 US troops had lost their lives in Vietnam; as many as 541,000 Americans were fighting there at the war’s height, and $150 billion was spent on the war effort.

Détente and Arms Control

President Nixon redirected American foreign and national security policy. He sought to minimize future Soviet challenges by treating the Soviet Union less as a rival and more as a partner in the international system. Known as détenteUS policy of cooperating with the Soviet Union within the context of continuing competition and conflict., the goal was to create a framework of limited cooperation between the two superpowers within the context of ongoing competition and conflict.Coral Bell, The Diplomacy of Détente: The Kissinger Era (New York: St. Martin’s, 1977).

Détente’s greatest success was in the area of arms control, most notably with the signing of the SALT I and SALT II agreements, which placed outer limits on the size of the American and Soviet nuclear forces.Thomas C. Schelling and Morton H. Halperin, Strategy and Arms Control (New York: Pergamon-Brassey’s Classic, 1985). These agreements slowed the arms race while maintaining the fundamental symmetry in US and Soviet nuclear forces around which deterrence had been built decades before.

The Carter Administration

President Jimmy Carter’s foreign policy emphasis on human rights pushed US–Soviet competition into the background.Robert C. Johansen, The National Interest and the Human Interest: An Analysis of U.S. Foreign Policy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1980); Debra Liang-Fenton, ed., Implementing U.S. Human Rights Policy (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2004). He criticized the human rights abuses of leaders who had loyally stood by the United States in its containment of the Soviet Union. One of those criticized was the shah of Iran. Put into power through a coup engineered by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in 1953, the shah had been one of America’s staunchest Cold War allies. But by the 1970s, he had become increasingly isolated within his own country.Stephen Kinzer, All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2002).

In January 1979, a revolution ousted the shah, who was replaced as leader in Iran by the exiled Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. When news broke in October that the shah was coming to the United States for medical treatment, Iranian militants seized the US embassy and held fifty-two Americans hostage. The Carter administration placed economic sanctions on Iran and undertook a failed hostage rescue mission in 1980. The hostages were not released until January 20, 1981, thirty minutes after Ronald Reagan became president.

The media reported the crisis night after night under such titles as “America Held Hostage.”

Link

“America Held Hostage” Logo of ABC’s Nightline

Night after night, the media reminded American policymakers and the public of the continuing hostage situation in Iran and of the inability of the US government to end it.

View the logo at http://pdxretro.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/nightline-iran.jpg.

Only a few diplomats were being held hostage, not the entire nation. Nonetheless, the media depiction conveying the impression of American impotence probably precipitated the rescue mission and contributed to making Jimmy Carter a one-term president.

The Reagan Administration

President Reagan rejected the notion that the United States could cooperate or work with the Soviet Union. Under Reagan, détente and arms control ceased guiding American foreign policy.

The deathblow to détente had come during the Carter administration when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979 in order to prop up pro-Russian Communist political forces. Within a year, the Soviet Union occupation army grew to 110,000, and it had to bear the primary responsibility for fighting the guerrillas, or Mujahedin, who were supported by US funds. American military aid to the Mujahedin rose from $120 million in 1984 to $630 million in 1987.

Support for the Mujahedin was consistent with the Reagan Doctrine that the purpose of American foreign policy not only was to contain the spread of Communism but also was to assist in bringing down Communist rulers.James M. Scott, Deciding to Intervene: The Reagan Doctrine and American Foreign Policy (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996).

Most controversial was the administration’s support for anticommunist forces in Nicaragua, where the Sandinistas had overthrown forty years of arbitrary, oppressive, and corrupt family rule in July 1979. The Sandinistas were sympathetic to Cuba’s Castro and hostile to the United States. In November 1981, Reagan authorized spending $19 million to transform a small and largely ineffective fighting force into one (the Contras) that would be more capable of ousting the Sandinista regime. In response, Congress passed the Boland Amendments, which barred the use of CIA or Defense Department funds for the purpose of overthrowing the Nicaraguan government or provoking a military exchange between it and Honduras. Chafing under this restriction, the Reagan administration devised a covert plan for increasing the amount of funds available to the Contras. At the heart of the administration’s plan was a scheme to divert money to the Contras from the covert sale of weapons to Iran. When it became public, the Iran-Contra affair produced widespread and mainly critical negative media coverage and a storm of controversy.

An Uncertain New World Order

On December 26, 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed. The end of the Cold War brought forward expressions of hope that America’s military involvement in the world might be lessened. For some this meant that a return to isolationism was possible; for others it meant that the United States would be able to engage in building democracy and promoting peaceful change.

These alternative visions of America’s role in the world were soon challenged by the reemergence of traditional national security concerns. The event that sparked this challenge was Iraq’s August 2, 1990, invasion of Kuwait. It led to the Persian Gulf War, the first major international conflict of the post–Cold War era.Michael J. Mazarr, Don M. Snider, and James A. Blackwell Jr., Desert Storm: The Gulf War and What We Learned (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1993).

The UN Security Council set January 15, 1991, as the deadline for Iraq’s peaceful exit from Kuwait and authorized member states to “use all means necessary” to bring about Iraq’s complete and unconditional withdrawal. When Iraq did not withdraw, the United States launched Operation Desert Storm. On February 28, after less than one month of fighting, Iraq announced a cease fire; on April 6, Iraq accepted the UN’s terms to formally end the war. The war was a diplomatic and military success for the United States, which put together a global coalition against Iraq and conducted a military campaign that produced relatively few American casualties.

Before the war, media coverage generally reflected the views of US policymakers and the military; it generated little debate over policy alternatives. The war itself was overwhelmingly reported from the perspectives of US policymakers and the military.W. Lance Bennett and David L. Paletz, eds., Taken By Storm: The Media, Public Opinion, and U.S. Foreign Policy in the Gulf War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

Key Takeaways

Two visions of foreign policy are isolationism and, dominant since World War II, internationalism. The main policies during the Cold War were containment, deterrence, détente and arms control, and the use of military force, as in Vietnam.

Exercises

- Why do you think the United States has historically been isolationist? Why might this have changed after World War II?

- What was the idea behind the Cold War policy of containment? How did the United States try to contain Soviet influence?

- What was the Reagan Doctrine? How did Reagan put it into practice?

17.4 The George W. Bush Administration

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What was the Bush Doctrine?

- How did military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq under George W. Bush begin?

- How have the media portrayed military engagements in Afghanistan and Iraq?

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, President George W. Bush focused on a policy of global leadership in a war on terrorism.For criticism of the Bush policy, see John E. Mueller, Overblown: How Politicians and the Terrorism Industry Inflate National Security Threats, and Why We Believe Them (New York: Free Press, 2006); and Louise Richardson, What Terrorists Want: Understanding the Enemy, Containing the Threat (New York: Random House, 2005). Media coverage and depictions would exaggerate terrorism and add to the importance of the war.Brigitte L. Nacos, Mass-Mediated Terrorism: The Central Role of the Media in Terrorism and Counterterror (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007).

The Afghanistan War

The first confrontation in this war came in Afghanistan, where Osama bin Laden, the acknowledged mastermind of the 9/11 attacks had taken refuge and where his terrorist organization, Al Qaeda, enjoyed support and protection from the ruling Taliban government.Bob Woodward, Bush at War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002).

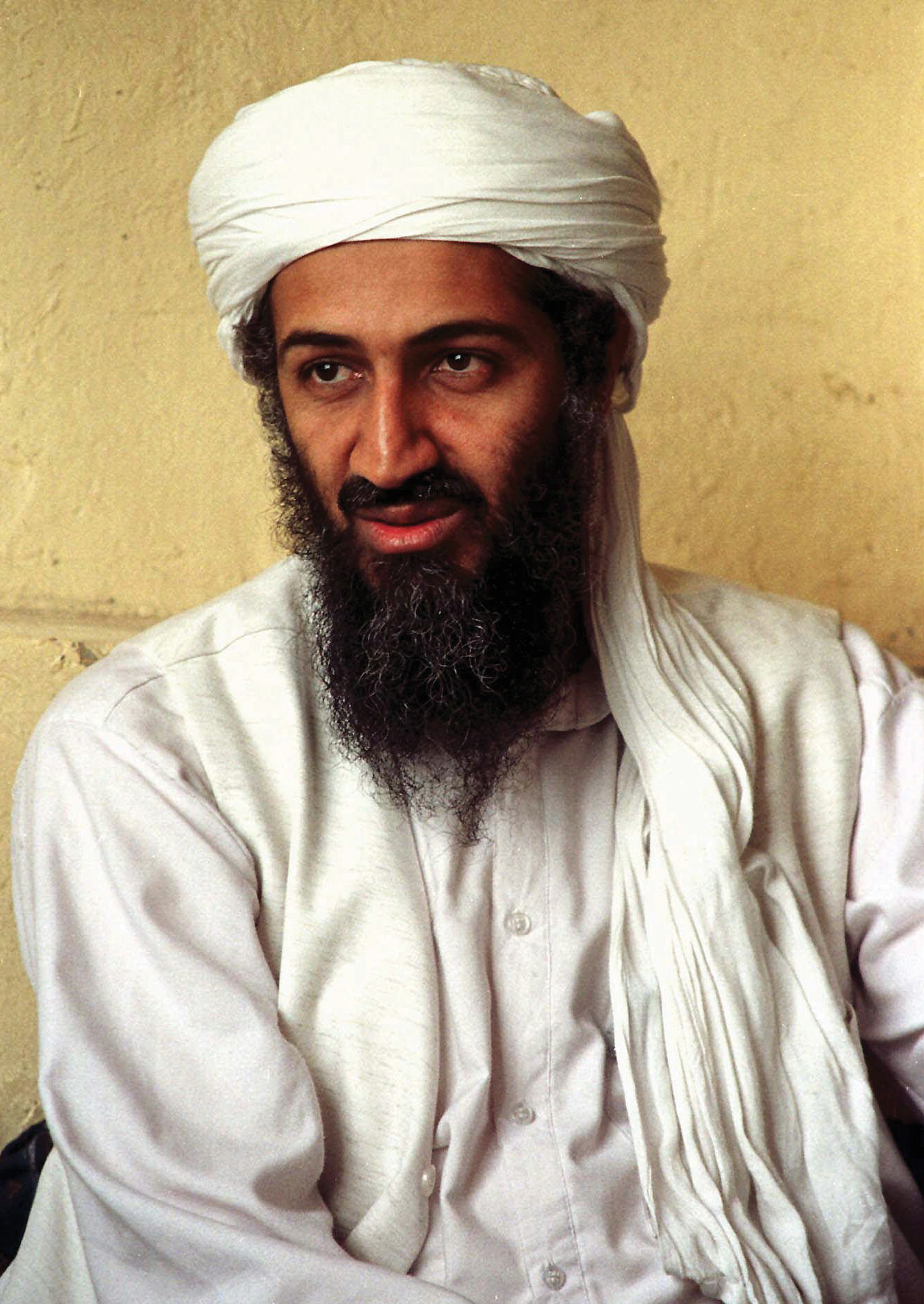

Figure 17.2 Osama bin Laden

The Saudi Arabian leader of Al Qaeda and mastermind of the 9/11 attacks symbolized terrorism for US policymakers and the media.

Source: Used with permission from AP Photo.

President Bush demanded that the Taliban expel Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda and sever its ties with international terrorism. When this did not happen, the United States and its allies began aerial strikes against terrorist facilities and Taliban military targets inside Afghanistan on October 7, 2001. Ground forces were supplied largely by the Northern Alliance, a coalition group that had opposed Taliban rule. Its efforts were aided and guided by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and US military forces. The Taliban soon surrendered, but its leader and Osama bin Laden remained at large.

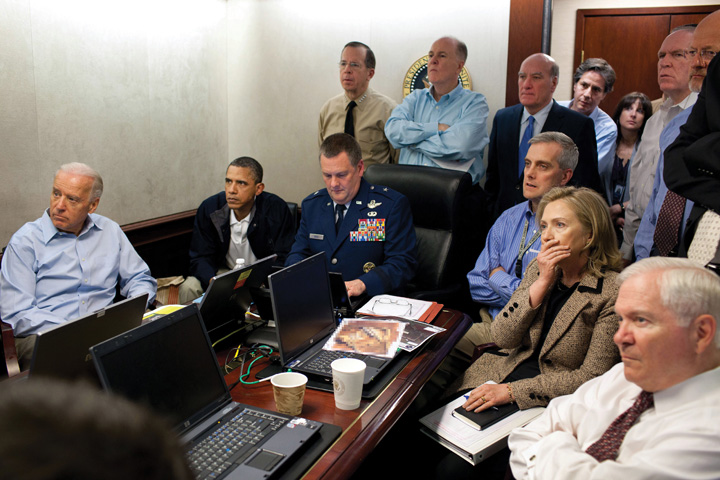

Figure 17.3 The Death of Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Laden would be killed on May 1, 2011, by US Navy Seals in his hideaway in Pakistan. In this photograph, released by the White House and shown around the world, we see the president, Vice President Joe Biden, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, and other members of the president’s national security team in the Situation Room as cameras mounted on the helmets of the attackers send video footage of the assault narrated from CIA headquarters by Director Leon Panetta.

Source: Photo courtesy of the White House (Pete Souza)http://www.flickr.com/photos/whitehouse/5680724572/.

In covering the war in Afghanistan, the US media reported a consensus among policymakers and the public on the need to defeat the Taliban; the media also focused on military strategy and its execution and paid little attention to the loss of life and destruction caused by the war. As CNN chairman Walter Isaacson wrote in a memo instructing its correspondents not to focus excessively on Afghan suffering, “We must redouble our efforts to make sure we do not seem to be simply reporting from their vantage or perspective.”Alessandra Stanley, “Battling the Scepticism of a Global Audience,” New York Times, November 1, 2001, B4.

Nation-building turned out to be far more difficult than overthrowing the Taliban. Some roads and buildings were rebuilt, and some girls, excluded from education by the Taliban, returned to school. Presidential elections, held in 2004 and 2009, were won by the more or less pro-US Hamid Karzai. There was little “security, stability, prosperity, or the rule of law.”The quote and information in this paragraph come from J. Alexander Thier, “A Chance of Success Slips Away,” New York Times, September 23, 2004, A27. Outside the capital of Kabul, Afghanistan was a collection of fiefdoms run by warlords and an opium-growing economy that fueled lawlessness and funded terrorists. The country’s Supreme Court was controlled by Islamic fundamentalists. Except for the election, Afghanistan was mostly forgotten and ignored by the US news media, whose attention largely turned to Iraq.

The Bush Doctrine

President George W. Bush outlined a new direction for American foreign and military policy. Known as the Bush Doctrine, it contained three interrelated themes.John Lewis Gaddis, “A Grand Strategy of Transformation,” Foreign Policy 130 (2002): 50–57.

First, predominance is the necessary foundation of American military strategy. The United States must possess a significant military power advantage over all other states so that it can act unilaterally (alone) to defend its national interests when and where it sees fit.

Second, the strategy for employing military power is preemptionPresident George W. Bush’s policy, exemplified in the war against Iraq, of removing threats before they harm the United States.. Rather than containment and deterrence, the United States will act first to remove threats before they are capable of harming it.

Third, in addition to reducing the military threat posed by other states, preemption has a goal of fostering regime change. Regime change is necessary because hostile states and terrorist organizations, the two principal threats to the United States through their possession of or attempts to possess weapons of mass destruction, are unlikely to change their ways. Only by removing them from power can the threat be eliminated.

Critics pointed out the limitations of preemption as a policy. In theory it should be applied to Iran and North Korea, which are hostile to the United States. But Iran could attack Israel and strike back against US forces in the region; and North Korea could unleash its nuclear weapons and invade South Korea. So under what circumstances and when should the policy be applied?

Given its heavy involvement of military and money in Iraq, moreover, did the United States have the resources to apply a preemption policy to any other countries? The National Guard and Reserve made up approximately 40 percent of US forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. The system is not designed to keep reservists on duty in a campaign against terrorism and fighting abroad for an extended period. Reservists train one weekend a month and two weeks a year, accelerated before deployment; thus many of them are ill prepared and lack combat skills.Ivo H. Daalder, James M. Lindsay, and James B. Steinberg, “The Bush National Security Strategy: An Evaluation,” Policy Brief #109 (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2002).

The Iraq War

The Bush Doctrine provided the strategic rationale for the Iraq War.Glenn P. Hastedt, Understanding the War in Iraq (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2004); Bob Woodward, Plan of Attack (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004). The diplomatic maneuvering leading up to war entered into the final phase on March 17, 2003, when President Bush addressed the nation and gave Saddam Hussein forty-eight hours to leave Iraq. Hussein rejected Bush’s ultimatum.

The first blow in the war was struck in the early morning hours of March 20, when President Bush ordered an air strike against the Iraqi leadership. The ground war began early in the evening of the same day, as American and British forces crossed into Iraq from Kuwait. Baghdad fell on April 9. On May 1, aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln, President Bush declared an end to major hostilities. In Iraq, celebrations of peace were short-lived as looting and anarchy soon became the order of the day, followed by insurgency and sectarian conflict. The United States soon went from liberator to occupier.

To build support for the war, the administration had claimed that Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was a major threat to the United States because he possessed biological, chemical, and perhaps nuclear weapons of mass destruction and was likely to supply them to terrorists. To make its case, the administration treated unclear or ambiguous information as certain facts (e.g., that Iraq had attempted to obtain uranium from Africa). It ignored intelligence questioning whether Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction and implied links between Saddam Hussein, 9/11, and terrorists that were never proven. The administration also used inflammatory language (e.g., “We don’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud” said National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice).

The Media in Support

Before the war, the media transmitted, parroted, promulgated, generally confirmed, and rarely challenged the administration’s scare campaign.Michael Massing, “Now They Tell Us,” New York Review, February 26, 2004, 43–49; also his exchanges with journalists from the New York Times, March 25, 2004, 45–46, and the Washington Post, April 8, 2004, 74–77; and Massing’s “Unfit to Print?,” New York Review, May 27, 2004, 6–10. For a strong dissent, arguing that media coverage of his speeches was biased against President Bush, see Jim A. Kuypers, Bush’s War: Media Bias and Justifications for War in a Terrorism Age (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006). The television networks’ coverage of domestic dissent was minimal, although they did report opposition from countries such as France arguing for a diplomatic solution.Danny Hayes and Matt Guardino, “Whose Views Made the News? Coverage and the March to War in Iraq,” Political Communication 27 (2010): 59–87.

The New York Times in particular supported the administration’s rationale for going to war with Iraq by accepting US government sources and Iraqi exiles’ claims at face value, displaying them on the front page under heavy-breathing headlines. The Times gave glowing coverage to Secretary of State Colin Powell’s speech and presentation of February 5, 2003, to the United Nations supposedly documenting Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction.

The Times undermined the credibility of Iraqi government denials by following them with challenges from US officials, and it discredited US and foreign sources critical of the administration’s argument. Stories challenging the administration’s case for war were downplayed: James Risen’s “C.I.A. Aides Feel Pressure in Preparing Iraqi Reports,” completed several days prior to the invasion, was not printed until three days after the start of the war and was then relegated to page B10.Daniel Okrent, “Weapons of Mass Destruction? Or Mass Distraction?,” New York Times, May 30, 2004, sec. 4, p. 2. Dissenters received little coverage.

Because the Times has a reputation for occasional skepticism about people in authority, its coverage gave credibility to the administration’s arguments. Moreover, many news organization, such as CNN and National Public Radio, follow the Times’ lead.

The lack of vigorous challenges by leaders of the Democratic Party to the Bush administration in the run-up to the war left little criticism of the Bush policy for the news media to transmit. But the Times’ coverage contributed to the Democrats’ docility. If the Times had published more critical stories, some Democrats could have been emboldened to attack the war policy.

Comparing Coverage

The Iraq War

Media coverage of the war itself was dramatically different depending on whether one was exposed to US or Arab media.This is based on Rami G. Khouri, “For the Full Story, Watch US & Arab TV,” Pacific News Service, March 26, 2003; James Poniewozik, “What You See vs. What They See,” Time, April 7, 2003, 68–69; and Jacqueline E. Sharkey, “The Television War,” American Journalism Review 25 (May 2003): 18.

In general, the US media supported the war, presenting it as “America against the enemy,” or as “us versus them.” Complexities were ignored: there were no in-depth stories on the history of Iraq, its factions (Kurds, Shiite, and Sunni Muslims); no understanding that, despite their hatred of Saddam Hussein, many Iraqis would not welcome the United States.

Television was most enthusiastic. Morning shows depicted the attack on Iraq as right and proper. Cable stations were unabashedly patriotic: Fox News titled its coverage “Op. Iraqi Freedom: War on Terror.” American flags were part of on-screen logos and backdrops. Many of the expert commentators were former high-ranking officers in the US military who were enthusiastically or at least guardedly prowar.

American reporters embedded with the invasion forces gave the troops’ perspective to their American audience. Reporters framed the conflict the same way as US officials and military commanders.

The war shown on American television networks and on cable was almost entirely bloodless. It featured the “video game” aspects of the technical wizardry of American military power.Sean Aday, “The Real World Will Never Get on Television: An Analysis of Casualty Imagery in American Television Coverage of the Iraq War,” in Media and Conflict in the 21st Century, ed Philip Seib (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 141–56. There was a dearth of gruesome or grisly footage. Reports repeated the Pentagon’s sanitized language: “degraded” for slaughtered Iraqi units, “softening up” for the exploding of Iraqi soldiers in their bunkers.

In dramatic contrast was the depiction of the war by Al Jazeera, the Qatar-based satellite television channel, dominated by Arab nationalists and Islamists, transmitting to a daily audience of thirty-five million across the Arab world. (The channel is barely seen in the United States.) It showed a different version of the war with different subjects and frames.

Al Jazeera had access to the Iraqi leadership. It placed correspondents and cameras in the Iraqi cities under attack and reported from the inhabitants’ perspectives. Its staff gave an Arab point of view to an Arab audience.

Al Jazeera did not ignore the American side. It reported the allied advances, had a reporter embedded with US forces, and broadcast sound bites from President Bush. But it debated rather than interviewed American spokespersons. It featured critics of the United States, took Iraqi government statements at face value, and highlighted any setbacks of the coalition forces.

Al Jazeera barely mentioned that the United States was opposing a brutal dictatorship. It depicted the US military as an invading, occupying force of ruthless killers. It broadcast a report from Iraqi television of pictures of dead US soldiers and interviews with captured ones. It showed raw and graphic footage of the destruction inflicted on Iraq and the pain and suffering of its civilians: charred bodies, mourning families, hospitals choked with bleeding and burned civilians.

It’s Not Over Until It’s Over

President Bush announced victory, but Iraq remained a country with ethnic and tribal divisions and religious fanatics following the dictates of clerics. Conflict continued, with insurgents attacking and killing US troops, Iraqi police, and public officials. Weapons of mass destruction were not found. The condition of the country’s infrastructure was dire. Many more billions of dollars were needed to pay for the war and reconstruction and to keep US troops in Iraq.

Elite consensus over the war evaporated. The revitalized Democratic opposition was reflected in Vermont Governor Howard Dean’s campaign for the party’s 2004 presidential nomination. He called the war precipitous and poorly prepared. The 9/11 Commission found that Iraq had no collaborative relationship with Al Qaeda and no involvement in the attacks on the World Trade Center. The former head of counterterrorism at the National Security Council contended that before the attacks, the Bush White House did not treat the danger of Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda as urgent. He confirmed that the possibility of attacking Iraq was on the administration’s policy agenda before 9/11.Richard A. Clarke, Against All Enemies: Inside America’s War on Terror (New York: Free Press, 2004); for a more sympathetic view of President Bush, see Bob Woodward, Bush at War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002).

Media coverage of Iraq turned critical. There were frequent reports of bombings, suicide attacks, and stories of people kidnapped and beheaded. There was a media feeding frenzy of revelations about and photographs of torture by US personnel and private contractors in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq and in Afghanistan.Seymour M. Hersh, Chain of Command: The Road from 9/11 to Abu Ghraib (New York: HarperCollins, 2004).

Figure 17.4 Abu Ghraib Prisoner “Gilligan” Hooded, Caped, and Wired on His Box

Photographs such as this, shown around the world, undermined the US claim to be a liberator not an occupier of Iraq.

Key Takeaways

The Bush Doctrine was three-pronged: it featured predominance, preemption, and regime change as the pillars of US foreign policy. The US therefore conducted military operations in Afghanistan in response to the 9/11 attacks. President George W. Bush’s doctrine of preemption then involved the United States in a war to overthrow the ruling regime in Iraq. While the media initially gave favorable coverage to the decision to go to war and to the military operations in Iraq, subsequent revelations about errors made both before and during the war brought about media criticism of the administration’s decision to go to war and its conduct of the war.

Exercises

- What is meant by preemption? What are some the potential problems with a policy of preemption?

- What was the justification for invading Afghanistan? How did the American media cover the war in Afghanistan?