This is “The Courts”, chapter 15 from the book 21st Century American Government and Politics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 15 The Courts

Preamble

A brief item in the Washington Post titled “A Nation of Stooges” reported that, in a nationwide poll, fewer than 50 percent of Americans could name one justice of the Supreme Court and only 17 percent could name three. In contrast, 59 percent of the people could identify the character names of the comedic trio The Three Stooges.Richard Morin, “A Nation of Stooges,” Washington Post, October 8, 1995, C5.

This is the kind of cute item the media relish reporting; they have, as noted in the aforementioned article, fun with “new facts and hot stats from the social sciences.” But the comparison is unfair. The Stooges appeared in close to two hundred short movies still shown on television. Years after their deaths, they remain cult figures with apparel, toys, and candy merchandised in their name. In contrast, Supreme Court justices usually crave anonymity, avoid publicity, keep cameras out of their courtroom, and rarely appear on television.

In fact, the public’s knowledge of the Supreme Court and the justices is greater than most surveys indicate.James L. Gibson and Gregory A. Caldeira, Citizens, Courts and Confirmations: Positivity Theory and the Judgments of the American People (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009). Moreover, the media are much to blame that it is not higher: their coverage of the Court is sparse compared to that of the president and Congress.

15.1 The US Legal System

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What are the differences between civil and criminal cases, and how are these cases usually resolved?

- How do the news and entertainment media depict trials?

- How are the federal courts organized?

- How does the Supreme Court work?

The American legal system handles a vast number of disputes and controversies. Our concern in this text is with civil and criminal cases, the main ways by which courts wield power and influence and make policy.Patricia Ewick and Susan S. Silbey, The Common Place of Law (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 18–19.

Civil Cases

In civil cases, plaintiffs (people or organizations) initiate lawsuits against defendants; courts resolve disputes by deciding or mediating between the two sides. Civil cases can involve money, contracts, property, personal injury, divorce, or child custody. “I’ll sue you” is a threat to instigate a civil action.

The vast majority of civil cases, some seventeen million annually, are filed in state courts, compared to around four hundred thousand in federal courts. State and federal laws establish the type of civil cases their courts can hear. For example, because there is no federal divorce law, all divorce cases are heard in state courts; because Social Security is a federal program, all civil disputes involving it are heard in federal courts.

Because of their costs and the often lengthy delays until they are heard in court, only about 1.3 percent of civil suits filed go to trial. Most civil cases are resolved by other means, such as settlements, plea deals, mediation, or arbitration.

Criminal Cases

Criminal cases are initiated by the government. They run the gamut from misdemeanors, such as trespassing and disorderly conduct, to felonies, such as armed robbery, rape, and murder. Unlike civil cases, criminal cases can result in the loss of liberty: a jail sentence. Around seven million people in the United States are either in prison, on probation, or on parole for crimes committed.

Most criminal laws are passed by states, and the vast majority of criminal cases originate in state courts: roughly twenty-one million criminal cases annually, compared to about seventy-six thousand in federal courts.

Around 27 percent of the criminal cases heard in federal courts involve alleged violations of federal drug laws. Often requiring mandatory sentences without parole, these federal laws are much tougher than state laws, so it makes an enormous difference whether a drug offense case is tried in a federal or state court.

Only about 4 percent of criminal cases are decided by trial. Prosecutors drop, or do not continue with charges, on another 25 percent. Most of the rest are resolved by guilty pleas without going to trial. Even for murder or manslaughter, a majority of defendants plead guilty. This often entails a plea bargainAgreement whereby a defendant agrees to plead guilty in return for a lighter sentence, a reduced charge, or both., in which defendants plead guilty in exchange for a reduced charge. The judge must approve the plea bargain.

Except for affluent defendants with high-powered and well-paid attorneys, people involved in criminal cases have an incentive to plea bargain. Defendants who insist on going to trial face sentences that can be far longer than those received by defendants who plead guilty and cooperate with the government. For lawyers and judges, plea bargains save both time and trial costs and also lighten their workloads. Because so many plead guilty, forty-seven million Americans have criminal records.Amy Beach, Ordinary Injustice: How America Holds Court (New York: Metropolitan, 2009).

Media Depictions of Trials

Dubbed “tabloid justice,” news depictions of the criminal justice system, especially on cable television, focus on dramatic, sensational, and lurid cases.Richard L. Fox, Robert W. Van Sickel, and Thomas L. Steiger, Tabloid Justice: Criminal Justice in an Age of Media Frenzy, 2nd ed. (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2007). A notorious instance was the Duke University lacrosse team rape story, which provoked a prodigious amount of often erroneous news coverage as well as outrageous opinions and judgments (notoriously from television commentator Nancy Grace) from March 2006 until April 2007, when all charges against the students were dropped and the case dismissed.

The types of cases receiving excessive and inflammatory coverage include those of a basketball star (Kobe Bryant) charged with rape; an actor (Robert Blake) accused of killing his wife; a decorating diva (Martha Stewart) charged with lying to the FBI; a pop star (Michael Jackson) accused of molesting children; and a mother (Casey Anthony) accused of killing her daughter. The media want, as the chief executive of truTV (formerly Court TV) put it, “the type of trials that have all the melodrama of a soap opera.”Quoted in Lola Ogunnaike, “As Court TV Gets Even Bolder, So Does Its Star,” New York Times, December 2, 2004, B1.

Figure 15.1 Judge Judy and Judge Joe Brown

Many people’s understanding of and opinions about courts are based on watching television’s fictional judges.

Source: Photo (left) courtesy of Susan Roberts, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Judge_Judy.jpg. Photo (right) courtesy of Phil Konstantin, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Joebrown.jpg.

Even trials covered live on television may be unrealistic examples of how the US criminal justice system operates. The trial of O. J. Simpson, accused of the murder of his ex-wife and a friend of hers, attracted huge attention from the news media and the public during the mid-1990s. Simpson was a celebrity defendant with sufficient wealth to hire a cast of attorneys and undergo a lengthy trial. In reality, most criminal trials take little time. The Los Angeles Superior Court disposed of nearly fifty-two thousand cases between the time of Simpson’s arrest and his acquittal.“Simpson Trial and Trivia,” US News & World Report, October 15, 1995, 43.

Trials are a staple of entertainment drama.See Timothy O. Lenz, Changing Images of Law in Film & Television Crime Stories (New York: Peter Lang, 2003); and Anthony Chase, Movies on Trial: The Legal System on the Silver Screen (New York: New Press, 2002). Many television series and their spin-offs involve trials. These shows differ drastically from the reality of courts and trials through the addition of drama and emotion: the highlights of cross-examination, attorneys browbeating witnesses and making speeches, and the guilty confessing. They rarely contain procedural elements, and the issues of “jurisdiction, notices to defendants, pleadings, discovery, and choice of a judge or jury trial, all of which can be argued, replied to, and motioned against.”Wende Vyborney Dumble, “And Justice for All,” in Television Studies, ed. Gary Burns and Robert J. Thompson (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1989), 106. As David E. Kelley, creator of The Practice and a former lawyer said, “I am writing the world of law in the way I would like it to be. It’s all a conceit, because most trials are boring.”Thane Rosenbaum, “Where Lawyers with a Conscience Get to Win Cases,” New York Times, May 12, 2002, AR 23.

Relatedly, trial judges are usually portrayed on television as legitimate and judicious, and their decisions almost always as correct. Consider the pseudorealistic television courtroom shows represented by Judge Judy and Judge Joe Brown.

The prevalence of courtroom shows is a testament to their appeal and to television’s need for cheap and relatively easy-to-produce programming. Frequent viewers believe that judges should—as these “judges” do—ask questions, be aggressive with litigants, express views about their testimony, and make known their opinions about the outcome of the cases.Kimberlianne Podlas, “Should We Blame Judge Judy? The Messages TV Courtrooms send Viewers,” Judicature 86, no. 1 (July–August 2002): 38–43. This is, in fact, the opposite of how most real judges behave.

Organization of the Federal Courts

The first sentence of Article III of the US Constitution created the US Supreme Court—a major innovation. The Articles of Confederation made no provision for a federal judiciary, only for courts created and controlled by the states.

Article III also gave Congress the authority to create lower federal courts. After the Constitution was ratified in 1789, Congress quickly did so through the Judiciary Act of 1789.

Link

The Judiciary Act

Learn more about the Judiciary Act of 1789 online at http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/judiciary.html.

The Federal District and Appeals Courts

There are 94 federal district courts staffed by 667 permanent and several temporary judges. Every state has at least one district with a district court in it responsible for hearing cases that arise within that geographic area.

Above the district courts are the federal courts of appeal. They decide whether or not district courts have made an error in conducting a trial. Judges on appeal courts base their rulings on written and oral legal arguments presented by lawyers for each side. There are no witnesses, no testimony, and no jury. Appellate courts answer questions of law rather than questions of fact.

There are currently thirteen courts of appeals, twelve of them based on geographic districts called “circuits.” There are eleven numbered circuits, each of which has jurisdiction over several states. No state straddles more than one circuit.

There is a twelfth circuit for the District of Columbia (known as the “DC Circuit”). The thirteenth circuit is the court of appeals for the “Federal Circuit,” which hears appeals from US Courts of Federal Claims, International Trade, the Patent and Trademark Office, and others. There are approximately 179 judges on the courts of appeals.

A case in district court is usually presided over by one judge, whereas an appeal before a court of appeals is typically heard by a panel of three judges. A majority vote of the panel is necessary to overturn a lower-court ruling. The court of appeals issues a written ruling explaining its decision.

Every litigant in federal court has the right to appeal an unfavorable ruling from the district court. However, because it is expensive to appeal, only about 17 percent of eligible litigants do so. Moreover, higher courts hear few of the cases appealed and rarely reverse lower-court decisions.Donald R. Songer, Reginald S. Sheehan, and Susan B. Haire, Continuity and Change on the United States Courts of Appeals (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000).

The Supreme Court

The Supreme Court, the nation’s highest tribunal, hears cases arising under the Constitution or the laws of the United States. The Constitution gives Congress the authority to set the number of Supreme Court justices, and it has changed the number several times. The Court started with five justices; it now has nine.

The Constitution does not stipulate any specific qualifications, not even a minimum age or legal training, for Supreme Court justices and other federal judges. Of the over one hundred individuals who have served on the Supreme Court, all except four women and two African American males have been white men.

How the US Supreme Court Works

Article III and the Eleventh Amendment of the Constitution require that the Supreme Court be the first court to hear certain types of cases. This original jurisdiction is limited to cases

- between the United States and one of the states,

- between two or more states,

- involving foreign ambassadors or other ministers,

- brought by one state against citizens of another state or against a foreign country.

Only about 1 percent of the Supreme Court’s cases fall under its original jurisdiction. The rest reach it as appeals from civil and criminal cases that have been decided by lower federal and by state courts. As the highest appellate court in the nation, the Supreme Court is the ultimate arbiter in many areas of the law.

If the case involves a federal question, an appeal can be made from the state’s appellate court of last resort to the US Supreme Court. A federal question exists if a state law is alleged to violate federal law (an act of Congress), a treaty ratified by the US Senate, or the US Constitution; or because something that state officials do is claimed to violate the Constitution or federal law. Grounds for appeal include evidence gathered from an unreasonable search and seizure, a coerced confession, and infringement of a constitutional right to a fair trial.

With rare exceptions, the Supreme Court has absolute control over the appeals it chooses to hear. Of the roughly eight thousand cases appealed to the Court every year, the justices typically agree to review a few hundred.

The justices normally decide around seventy of these with comprehensive written opinions during the Court’s annual term from October through late June to early July. The Court occasionally issues per curiam decisionsShort, unsigned opinion by the Supreme Court, usually for cases it decides without oral argument.: brief unsigned opinions, usually for cases it decides without oral argument.

The justices do not have to give any reasons for accepting or rejecting a case. Even after deciding to hear a case, they can change their minds and “DIG” (dismiss as improvidently granted)To refuse to hear a case after initially accepting it. Supreme Court justices may change their minds about hearing a case without giving any reason. it: in other words, they say that they won’t decide the case after all, again without giving any reason.

Writ of Certiorari

Most cases reach the Court by way of a writ of certiorariPetition asking the Supreme Court to review a case.. Certiorari is Latin for “to make more certain.” Litigants who receive an adverse ruling in the federal appeals courts or, in cases involving a federal question, from a state’s highest appellate court can submit a petition for a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court, asking it to review the case.

It takes four of the nine justices to “grant cert.” This is called the Rule of FourRule stipulating that at least four justices of the Supreme Court must vote to accept an appealed case before it can be heard.. If the Supreme Court does not grant cert, the lower court ruling is left standing. This does not mean that the Supreme Court agrees with that ruling, only that the Court has chosen not to review it.

When the Supreme Court grants cert, it is usually because four or more of the justices believe the case represents an important issue, such as an unresolved constitutional or statutory question on which they are interested in ruling. Sometimes disputes between different courts need to be resolved, or Congress and lower courts need the Court’s guidance on the Constitution. However, it is not unknown for justices to avoid granting cert to important cases because they do not want to rule on them.Lisa A. Kloppenberg, Playing It Safe: How the Supreme Court Sidesteps Hard Cases and Stunts the Development of Law (New York: New York University Press, 2001).

The Solicitor General

The case for cert is strengthened if it is backed by the solicitor generalJustice department official responsible for presenting the position of the presidential administration before the courts., the presidential appointee in the justice department responsible for presenting the position of the US government to the courts. The solicitor general screens cases before most agencies of the federal government can appeal them to the Court. Consequently, more than half of the Supreme Court’s workload comes from cases under the solicitor general. The justices pay special attention to the recommendations of the solicitor general, nicknamed “the 10th Justice” in the news.

Link

The Solicitor General’s Office

Visit the solicitor general’s office online at http://www.justice.gov/osg.

Briefs

When cert is granted, the lawyers for each side file a briefWritten argument presented to a court by lawyers on behalf of clients prior to a hearing. making their arguments. Others with a stake in the outcome of the case may, with the permission of the Court, each file an amicus curiae briefBrief raising additional arguments, filed by a third party to a lawsuit. on behalf of one or the other parties to the case. (They may also persuade the Court to take a case.) These “friend of the court” briefs expose the justices to additional arguments and enable them, should they be so inclined, to gauge interest-group attention to a case and the amount of support from the different sides.Paul M. Collins Jr., Friends of the Court: Interest Groups and Judicial Decision Making (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Oral Arguments

After reviewing the briefs, the justices hear oral arguments, usually limited to an hour split equally between the sides. The justices often interrupt the attorneys with questions, probe arguments made in the briefs, and raise new issues; they may indicate their thinking about the case and possible decision. The arguments can be used by the justices to reach the legal and policy decisions that they preferTimothy R. Johnson, Oral Arguments and Decision Making on the United States Supreme Court (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2004).—unless, that is, one side’s lawyer makes a more convincing argument than the other.Timothy R. Johnson, Paul J. Wahlbeck, James F. Spriggs II, “The Influence of Oral Arguments on the U.S. Supreme Court,” American Political Science Review 100 (February 2006): 99–113. Oral arguments are the only public part of the Supreme Court’s work.

Link

Oral Arguments Heard by the Supreme Court

Find and listen to archived oral arguments online at http://www.oyez.org.

Law Clerks

Each justice selects a few law clerksAssistants to Supreme Court justices, selected to assist them in researching cases, deciding which ones to accept, and drafting opinions. (usually four) to assist in researching cases, deciding which ones to accept, and drafting opinions. These clerks are usually honors graduates from the most prestigious law schools.

A clerkship betokens a promising future in the legal profession. Because the clerks’ work is confidential and rarely revealed, the extent of justices’ reliance on their clerks is uncertain. One former clerk writing about the Court charged that the justices granted “great and excessive power to immature, ideologically driven clerks, who in turn use that power to manipulate their bosses.”Edward Lazarus, Closed Chambers: The First Eyewitness Account of the Epic Struggles Inside the Supreme Court (New York: Times Books, 1998), 6. Yet, most justices are so self-confident and versed in the law that it is hard to imagine them being led to make decisions against their will.

Opinions

Some time after oral arguments, the justices meet in a conference and vote in order of seniority, starting with the chief justice, on how the case should be decided.

Link

Supreme Court Decisions

Read archived Supreme Court decisions online at http://www.findlaw.com/casecode/supreme.html.

The Supreme Court decides cases by majority rule: at least five of the nine justices need to agree for a majority opinionDecision by a majority of the members of the Supreme Court.. They do not, however, have to agree on the reasons for their decision. It is possible for a majority to be composed of justices who agree on their rationale for the decision plus justices who join the decision (but for other reasons) and thus write a joint or individual concurring opinionDecision by a Supreme Court justice that agrees with the majority decision, but for different reasons.. Justices who disagree with the majority opinion almost always write a dissenting opinionDecision by one or more Supreme Court justice that disagrees with the majority decision. or join in a colleague’s dissenting opinion, explaining why they think the majority was wrong. On rare occasions, when a justice wants to make a dramatic statement arguing that the majority is profoundly wrong, she or he will read this written dissent aloud.

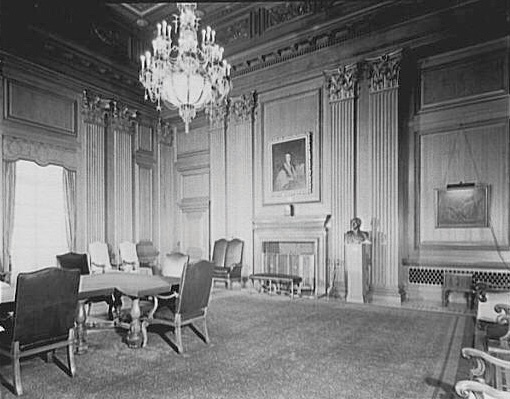

Figure 15.2 Conference Room of the Supreme Court

The intimacy of the Supreme Court is best captured by the conference room where the nine justices meet to vote on which cases to hear, to discuss opinions, and to decide cases. The junior member of the Court is responsible for opening and closing the doors.

Source: Photo by Theodor Horydczak, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/thc1995011442/PP/.

Bargaining and compromise sometimes ensue in an effort to create a majority coalition.The classic early study of such bargaining is Walter Murphy’s Elements of Judicial Strategy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964); see also Forrest Maltzman, James F. Spriggs II, and Paul J. Wahlbeck, Crafting Law on the Supreme Court (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000); and Saul Brenner and Joseph W. Whitmeyer, Strategy on the United States Supreme Court (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009). A study of justices’ conference notes concludes that the Court’s decisions come from “an intricate and shifting composite of law, politics, policy, principle, efficiency, expedience, pragmatism, dogmatism, reason, passion, detachment, individual personality, group psychology, institutional forces, and external pressures.”Del Dickson, ed., The Supreme Court in Conference (1940–1985): The Private Discussions Behind Nearly 300 Supreme Court Decisions (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), xxvii. To this list, we would add the desire for approval from social groups with which they identify or associate and from the legal community of law professors and law students.Lawrence Baum, Judges and Their Audiences: A Perspective on Judicial Behavior (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006).

The chief justice, if voting with the majority, determines who will write its opinion. Thus many of the Court’s most important decisions are penned by the chief justice. If the chief justice is not in the majority, the justice in the majority who has served on the Court the longest takes on the assignment.

Key Takeaways

Coverage of most criminal cases is decided by plea bargains. A few trials attract abundant coverage in news and entertainment media, which depict them unrealistically. The federal court system consists of ninety-four district courts, with at least one in each state, and thirteen appeals courts, each one with jurisdiction over several states. At the top of the judicial system is the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court’s decisions entail briefs, oral arguments, conferences, clerks, and opinions.

Exercises

- Why do you think the media devotes more coverage to the president and to Congress than to the Supreme Court? What impression of our legal system do you get from the media?

- Why do you think our legal system makes a distinction between civil and criminal cases? What are the key differences between the two types of cases?

- How many Supreme Court decisions can you name? How might your life be different if those cases had been decided differently?

15.2 Power of the US Supreme Court

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What is judicial review?

- Why is Marbury v. Madison important?

- What is judicial power and how is it constrained?

- What are the leading judicial philosophies?

In Federalist No. 78, Alexander Hamilton described the courts as “the least dangerous” branch of government. Yet, they do possess considerable power. For example, because of the Court’s 5–4 decision in 2002, the more than seven million public high school students engaged in “competitive” extracurricular activities—including cheerleading, Future Farmers of America, Spanish club, and choir—can be required to submit to random drug testing.Board of Education v. Earls, 536 US 822 (2002).

Judicial Review

The federal courts’ most significant power is judicial reviewThe authority of the federal courts, especially the Supreme Court, to decide whether a state or federal law violates the US Constitution.. Exercising it, they can refuse to apply a state or federal law because, in their judgment, it violates the US Constitution.

Marbury v. Madison

Judicial review was asserted by the US Supreme Court in 1803 in the decision of Chief Justice John Marshall in the case of Marbury v. Madison (5 US 137, 1803).

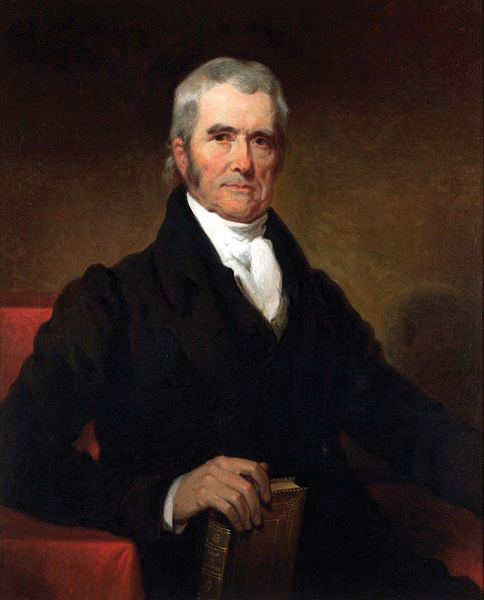

Figure 15.3 John Marshall

Marshall was chief justice of the Supreme Court from 1801 to 1835 and the author of many decisions, including Marbury v. Madison.

Source: Painting by Henry Inman, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Marshall_by_Henry _Inman,_1832.jpg.

After losing the election of 1800, John Adams made a flurry of forty-two appointments of justices of the peace for Washington, DC in the last days of his presidency. His purpose in doing so was to ensure that the judiciary would remain dominated by his Federalist party. The Senate approved the appointments, and Secretary of State John Marshall stamped the officials’ commissions with the Great Seal of the United States. But no one in the outgoing administration delivered the signed and sealed commissions to the appointees. The new president, Thomas Jefferson, instructed his secretary of state, James Madison, not to deliver them. One appointee, William Marbury, sued, asking the Supreme Court to issue a writ of mandamus, a court order requiring Madison to hand over the commission.

The case went directly to the Supreme Court under its original jurisdiction. John Marshall was now chief justice, having been appointed by Adams and confirmed by the Senate. He had a dilemma: a prominent Federalist, he was sympathetic to Marbury, but President Jefferson would likely refuse to obey a ruling from the Court in Marbury’s favor. However, ruling in favor of Madison would permit an executive official to defy the provisions of the law without penalty.

Marshall’s solution was a political masterpiece. The Court ruled that Marbury was entitled to his commission and that Madison had broken the law by not delivering it. But it also ruled that the part of the Judiciary Act of 1789 granting the Court the power to issue writs of mandamus was unconstitutional because it expanded the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court beyond its definition in Article III; this expansion could be done only by a constitutional amendment. Therefore, Marbury’s suit could not be heard by the Supreme Court. The decision simultaneously supported Marbury and the Federalists, did not challenge Jefferson, and relinquished the Court’s power to issue writs of mandamus. Above all, it asserted the prerogative of judicial review for the Supreme Court.This discussion is based in part on Jean Edward Smith, John Marshall: Definer of a Nation (New York: Holt, 1996), introduction and chap. 13. For an analysis of the distinction between judicial review and judicial supremacy (the obligation of officials to follow the Court’s reasoning in the future), and the politics involved in the latter, see Keith E. Whittington, Political Foundations of Judicial Supremacy: The Presidency, the Supreme Court, and Constitutional Leadership in US History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007).

Judicial Review Assessed

For forty years after Marbury, the Court did not overturn a single law of Congress. And when it finally did, it was the Dred Scott decision, which dramatically damaged the Court’s power. The Court ruled that people of African descent who were slaves (and their descendants, whether or not they were slaves) were not protected by the Constitution and could never be US citizens. The Court also held that the US Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in federal territories.Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 US 393 (1857).

The pace of judicial review picked up in the 1960s and continues to this day. The Supreme Court has invalidated an average of eighteen federal laws per decade. The Court has displayed even less compunction about voiding state laws. For example, the famous Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas desegregation case overturned statutes from Kansas, Delaware, South Carolina, and Virginia that either required or permitted segregated public schools. The average number of state and local laws invalidated per decade is 122, although it has fluctuated from a high of 195 to a low for the period 2000–2008 of 34.Lawrence Baum, The Supreme Court, 10th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2010).

Judicial review can be seen as reinforcing the system of checks and balances. It is a way of policing the actions of Congress, the president, and state governments to make sure that they are in accord with the Constitution. But whether an act violates the Constitution is often sharply debated, not least by members of the Court.

Constraints on Judicial Power

There are three types of constraints on the power of the Supreme Court and lower court judges: they are precedents, internal limitations, and external checks.

Ruling by Precedent

Judges look to precedentA previous court decision used to guide and justify the Court’s decision in a similar case., previously decided cases, to guide and justify their decisions. They are expected to follow the principle of stare decisis, which is Latin for “to stand on the decision.” They identify the similarity between the case under consideration and previous ones. Then they apply the rule of law contained in the earlier case or cases to the current case. Often, one side is favored by the evidence and the precedents.

Precedents, however, have less of an influence on judicial power than would be expected. According to a study, “justices interpret precedent in order to move existing precedents closer to their preferred outcomes and to justify new policy choices.”Thomas G. Hansford and James F. Spriggs II, The Politics of Precedent on the U.S. Supreme Court (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006), 130.

Precedents may erode over time. The 1954 Brown school desegregation decision overturned the 1896 Plessy decision that had upheld the constitutionality of separate but equal facilities and thus segregation.Plessy v. Ferguson, 153 US (1896); Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, 347 US 484 (1954). Or they may be overturned relatively quickly. In 2003, the Supreme Court by 6–3 struck down a Texas law that made homosexual acts a crime, overruling the Court’s decision seventeen years earlier upholding a similar antisodomy law in Georgia. The previous case “was not correct when it was decided, and it is not correct today,” Justice Kennedy wrote for the majority.The earlier case was Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 US 1861 (1986); it was overruled by Lawrence v. Texas, 02-102 (2003).

Judges may disagree about which precedents apply to a case. Consider students wanting to use campus facilities for prayer groups: if this is seen as violating the separation of church and state, they lose their case; if it is seen as freedom of speech, they win it. Precedents may allow a finding for either party, or a case may involve new areas of the law.

Internal Limitations

For the courts to exercise power, there must be a case to decide: a controversy between legitimate adversaries who have suffered or are about to suffer in some way. The case must be about the protection or enforcement of legal rights or the redress of wrongs. Judges cannot solicit cases, although they can use their decisions to signal their willingness to hear (more) cases in particular policy areas.

Judges, moreover, are expected to follow the Constitution and the law despite their policy preferences. In a speech to a bar association, Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens regretted two of his majority opinions, saying he had no choice but to uphold the federal statutes.Linda Greenhouse, “Justice Weighs Desire v. Duty (Duty Prevails),” New York Times, August 25, 2005, A1. That the Supreme Court was divided on these cases indicates, however, that some of the other justices interpreted the laws differently.

A further internal limitation is that judges are obliged to explain and justify their decisions to the courts above and below. The Supreme Court’s written opinions are subject to scrutiny by other judges, law professors, lawyers, elected officials, the public, and, of course, the media.

External Checks on Power

The executive and legislative branches can check or try to check judicial power. Through their authority to nominate federal judges, presidents influence the power and direction of the courts by filling vacancies with people likely to support their policies.

They may object to specific decisions in speeches, press conferences, or written statements. In his 2010 State of the Union address, with six of the justices seated in front of him, President Obama criticized the Supreme Court’s decision that corporations have a First Amendment right to make unlimited expenditures in candidate elections.Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 US 50 (2010), discussed in Chapter 11 "Campaigns and Elections".

Presidents can engage in frontal assaults. Following his overwhelming reelection victory, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed to Congress in February 1937 that another justice be added to the Supreme Court for each sitting justice over the age of seventy. This would have increased the number of justices on the court from nine to fifteen. His ostensible justification was the Court’s workload and the ages of the justices. Actually, he was frustrated by the Court’s decisions, which gutted his New Deal economic programs by declaring many of its measures unconstitutional.

The president’s proposal was damned by its opponents as unwarranted meddling with the constitutionally guaranteed independence of the judiciary. It was further undermined when the justices pointed out that they were quite capable of coping with their workload, which was not at all excessive. Media coverage, editorials, and commentary were generally critical, even hostile to the proposal, framing it as “court packing” and calling it a “scheme.” The proposal seemed a rare blunder on FDR’s part. But while Congress was debating it, one of the justices shifted to the Roosevelt side in a series of regulatory cases, giving the president a majority on the court at least for these cases. This led to the famous aphorism “a switch in time saves nine.” Within a year, two of the conservative justices retired and were replaced by staunch Roosevelt supporters.

Congress can check judicial power. It overcomes a decision of the Court by writing a new law or rewriting a law to meet the Court’s constitutional objections without altering the policy. It can threaten to—and sometimes succeed in—removing a subject from the courts’ jurisdiction, or propose a constitutional amendment to undo a Court decision.

Indeed, the first piece of legislation signed by President Obama overturned a 5–4 Supreme Court 2007 decision that gave a woman a maximum of six months to seek redress after receiving the first check for less pay than her peers.Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. 550 US (2007). Named after the woman who at the end of her nineteen-year career complained that she had been paid less than men, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act extends the period to six months after any discriminatory paycheck. It also applies to anyone seeking redress for pay discrimination based on race, religion, disability, or age.

The Constitution grants Congress the power to impeach judges. But since the Constitution was ratified, the House has impeached only eleven federal judges, and the Senate has convicted just five of them. They were convicted for such crimes as bribery, racketeering, perjury, tax evasion, incompetence, and insanity, but not for wrongly interpreting the law.

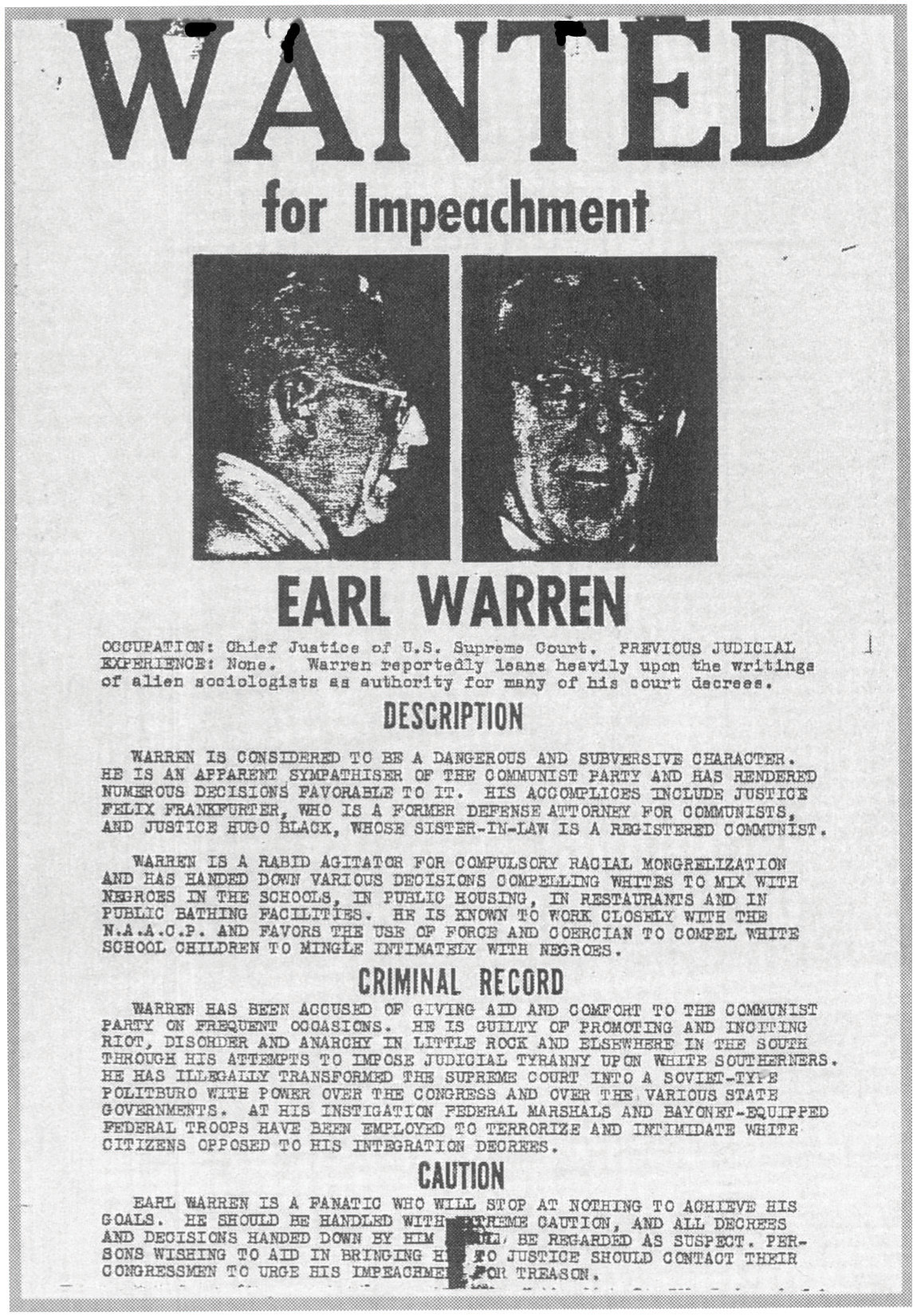

The Supreme Court may lose power if the public perceives it as going too far. Politicians and interest groups criticize, even condemn, particular decisions. They stir up public indignation against the Court and individual justices. This happened to Chief Justice Earl Warren and his colleagues during the 1950s for their school desegregation and other civil rights decisions.

Figure 15.4

The controversial decisions of the Warren Court inspired a movement to impeach the chief justice.

How the decisions and reactions to them are framed in media reports can support or undermine the Court’s legitimacy (Note 15.23 "Comparing Content").

Comparing Content

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas

How a decision can be reported and framed differently is illustrated by news coverage of the 1954 Supreme Court school desegregation ruling.

The New York Times of May 18, 1954, presents the decision as monumental and historic, and school desegregation as both necessary and desirable. Southern opposition is acknowledged but downplayed, as is the difficulty of implementing the decision. The front-page headline states “High Court Bans School Segregation; 9–0 Decision Grants Time to Comply.” A second front-page article is headlined “Reactions of South.” Its basic theme is captured in two prominent paragraphs: “underneath the surface…it was evident that many Southerners recognized that the decision had laid down the legal principle rejecting segregation in public education facilities” and “that it had left open a challenge to the region to join in working out a program of necessary changes in the present bi-racial school systems.”

There is an almost page-wide photograph of the nine members of the Supreme Court. They look particularly distinguished, legitimate, authoritative, decisive, and serene.

In the South, the story was different. The Atlanta Constitution headlined its May 18, 1954, story “Court Kills Segregation in Schools: Cheap Politics, Talmadge Retorts.” By using “Kills” instead of the Times’s “Bans,” omitting the fact headlined in the Times that the decision was unanimous, and including the reaction from Georgia Governor Herman E. Talmadge, the Constitution depicted the Court’s decision far more critically than the Times. This negative frame was reinforced by the headlines of the other stories on its front page. “Georgia’s Delegation Hits Ruling” announces one; “Segregation To Continue, School Officials Predict” is a second. Another story quotes Georgia’s attorney general as saying that the “Ruling Doesn’t Apply to Georgia” and pledging a long fight.

The Times’ coverage supported and legitimized the Supreme Court’s decision. Coverage in the Constitution undermined it.

External pressure is also applied when the decisions, composition, and future appointments to the Supreme Court become issues during presidential elections.Donald Grier Stephenson Jr., Campaigns and the Court: The U.S. Supreme Court in Presidential Elections (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999). In a May 6, 2008, speech at Wake Forest University, Republican presidential candidate Senator John McCain said that he would nominate for the Supreme Court “men and women with…a proven commitment to judicial restraint.” Speaking to a Planned Parenthood convention on July 17, 2007, Senator Barack Obama identified his criteria as “somebody who’s got the heart, the empathy, to recognize what it’s like…to be poor or African American or gay or disabled or old.”

Judges as Policymakers

Judges have power because they decide cases: they interpret the Constitution and laws, and select precedents. These decisions often influence, even make, public policy and have important ramifications for social conflict. For example, the Supreme Court has effectively established the ground rules for elections. In 1962 it set forth its “one person, one vote” standard for judging electoral districts.Baker v. Carr, 369 US 186 (1962). It has declared term limits for members of Congress unconstitutional. It has upheld state laws making it extremely difficult for third parties to challenge the dominance of the two major parties.See David K. Ryden, ed., The U.S. Supreme Court and the Electoral Process (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2000), especially the editor’s “Overview,” 1–4.

Judicial Philosophies

How willing judges are to make public policy depends in part on their judicial philosophies.For the argument that the justices’ behavior is largely determined by their individual policy preferences, see Jeffrey A. Segal and Harold J. Spaeth, The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002); see also Brian Z. Tamanaha, Beyond the Formalist-Realist Divide: The Role of Politics in Judging (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009). Some follow judicial restraintJudicial philosophy whereby judges decide cases on the narrowest grounds possible by, for example, deferring to the legislature’s decisions., deciding cases on the narrowest grounds possible. In interpreting federal laws, they defer to the views expressed in Congress by those who made the laws. They shy away from invalidating laws and the actions of government officials. They tend to define some issues as political questions that should be left to the other branches of government or the voters. When the Constitution is silent, ambiguous, or open ended on a subject (e.g., “freedom of speech,” “due process of law,” and “equal protection of the laws”), they look to see whether the practice being challenged is a long-standing American tradition. They are inclined to adhere to precedent.

Judicial restraint is sometimes paired with strict constructionismJudicial philosophy of applying the Constitution according to what the judges believe was its original meaning to a reasonable person when it was framed.. Judges apply the Constitution according to what they believe was its original meaning as understood by a reasonable person when the Constitution was written.

Other judges follow a philosophy of judicial activismJudicial philosophy whereby judges are willing to substitute their policy views for the policy actions or inaction of the other branches of government. (although they may not call it that). Activist judges are willing to substitute their policy views for the policy actions or inaction of the other branches of government.

Judicial activism is often paired with loose constructionismJudicial philosophy embodying the view that the Constitution requires interpretation to respond to changing public needs., viewing the Constitution as a living document that the founders left deliberately ambiguous. In interpreting the Constitution, these judges are responsive to what they see as changes in society and its needs. A plurality of the Supreme Court found a right to privacy implicit in the Constitution and used it to overturn a Connecticut law prohibiting the use of contraceptives.Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 US 479 (1965). The justices later used that privacy right as a basis for the famous Roe v. Wade decision, “discovering” a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion.

The distinction between judicial restraint and strict constructionism on the one hand and judicial activism and loose constructionism on the other can become quite muddy. In 1995, the Supreme Court, by a 5–4 vote, struck down the Gun-Free School Zone Act—an attempt by Congress to keep guns out of schools.United States, Petitioner v. Alfonso Lopez, Jr., 514 US 549 (1995). The ruling was that Congress had overstepped its authority and that only states had the power to pass such laws. This decision by the conservative majority, interpreting the Constitution according to what it believed was the original intentions of the framers, exemplified strict constructionism. It also exemplified judicial activism: for the first time in fifty years, the Court curtailed the power of Congress under the Constitution’s commerce clause to interfere with local affairs.In The Supreme Court and the American Elite, 1789–2008 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), Lucas A. Powe Jr. argues that the Court “serves ruling political coalitions” and attacks the conservative Rehnquist Court for overturning legislation that extended rights and privileges, and protected and improved society. A 5–4 conservative majority has also interpreted the Second Amendment to prohibit the regulation of guns.The cases are District of Columbia et al. v. Heller, 554 US (2008) and McDonald et al. v. City of Chicago et al. 561 US (2010). This decision, too, could be seen as activist.

Political Views in Action

One doesn’t have to believe that justices are politicians in black robes to understand that some of their decisions are influenced, if not determined, by their political views.For the argument that there is nothing wrong with a political court or with political motives in constitutional adjudication, see Terri Jennings Peretti, In Defense of a Political Court (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 73. Judges appointed by a Democratic president are more liberal than those appointed by a Republican president on labor and economic regulation, civil rights and liberties, and criminal justice.Robert A. Carp, Kenneth L. Manning, and Ronald Stidham, “President Clinton’s District Judges: ‘Extreme Liberals’ or Just Plain Moderates?” Judicature 84, no. 5 (March–April 2001): 282–88; and “The Decision-Making Behavior of George W. Bush’s Judicial Appointees: Far-Right, Conservative, or Moderate?” Judicature 88, no. 1 (July–August 2004): 20–29. Republican and Democratic federal appeals court judges decide differently on contentious issues such as abortion, racial integration and racial preferences, church-state relations, environmental protection, and gay rights.

On rare occasions, the Supreme Court renders a controversial decision that graphically reveals its power and is seen as motivated by political partisanship. In December 2000, the Court voted 5–4, with the five most conservative justices in the majority, that the Florida Election Code’s “intent of the voter” standard provided insufficient guidance for manually recounting disputed ballots and that there was no time left to conduct recounts under constitutionally acceptable standards.Bush v. Gore, 121 S. Ct. 525 (2000); also see David Margolick, Evgenia Peretz, and Michael Shnayerson, “The Path to Florida,” Vanity Fair, October 2004. This ensured that Republican George W. Bush would become president.

The decision was widely reported and discussed in the media. Defenders framed it as principled, based on legal considerations. Critics deplored it as legally frail and politically partisan. They quoted the bitter comment of dissenting Justice Stevens: “Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year’s presidential election, the identity of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the nation’s confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law.”Quoted in Linda Greenhouse’s analysis “Bush v. Gore: A Special Report; Election Case a Test and a Trauma for Justices,” New York Times, February 20, 2001, A1.

Key Takeaways

In this section, we have explained how judicial review originated, how it is exercised, and what its effects are. We described the power of the courts, especially of the Supreme Court, and how it may be constrained by precedent, internal limitations, and external pressures. Justices make policy and are influenced by their ideological views and judicial philosophies.

Exercises

- What role does judicial review play in our legal system? Why might it be important for the Supreme Court to have the power to decide if laws are unconstitutional?

- In Marbury v. Madison, how did Chief Justice Marshall strike a balance between asserting the Supreme Court’s authority and respecting the president’s authority? Do you think justices should take political factors into account when ruling on the law?

- Why do you think it might be important for judges to follow precedent? What do you think would happen if judges decided every case differently?

- Which of the four judicial philosophies described in the text makes the most sense to you? What do you think the advantages and disadvantages of that philosophy might be?

15.3 Selecting Federal Judges

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What factors influence the selection of federal judges?

- What is the confirmation process?

- Under what circumstances are the media important in the confirmation (or not) of Supreme Court nominees?

- Why are some nominations unsuccessful and others successful?

The president nominates all federal judges, who must then be approved by the Senate. President George W. Bush’s nominees were screened by a committee of fifteen White House and justice department officials headed by the White House legal counsel. They looked for ideological purity, party affiliation, and agreement with the president on policy issues and often turned to the Federalist Society, a conservative lawyers’ group, for nominees.

The appointments of judges to the lower federal courts are important because almost all federal cases end there.For a study of lower federal court selection, see Sheldon Goldman, Picking Federal Judges (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997). Through lower federal judicial appointments, a president “has the opportunity to influence the course of national affairs for a quarter of a century after he leaves office.”From Tom Charles Huston to President Richard Nixon, 25 March 1969, in WHCF ExFG 50, the Judicial Branch (1969–1970), Box 1, White House Central Files, FG 50, Nixon Presidential Materials Project, College Park, Maryland.

Once in office, federal judges can be removed only by impeachment and conviction. Unless compelled to retire due to illness or incapacity, judges may time their departures so that their replacements are appointed by a president who shares their political views and policy preferences.Lee Epstein and Jeffrey A. Segal, The Politics of Judicial Appointments (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005). Supreme Court Justice Souter retired in 2009 and Justice Stevens retired in 2010, enabling President Obama to nominate, and the Democratic-controlled Senate to confirm, their successors.

Choosing Supreme Court Justices

In nominating Supreme Court justices, presidents seek to satisfy their political, policy, and personal goals.Michael Comiskey, Seeking Justices: The Judging of Supreme Court Nominees (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004), thinks the confirmation process is acceptable and effective; but Christopher L. Eisgruber, The Next Justice: Repairing The Supreme Court Appointments Process (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007), wants the selection process to produce justices with moderate judicial philosophies; and Richard Davis, Electing Justice: Fixing the Supreme Court Nomination Process (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), thinks the process is a mess and proposes various ways of electing Supreme Court justices. They do not always succeed; justices sometimes change their views over time or may surprise the president from the start. “Biggest damfool mistake I ever made” said President Dwight D. Eisenhower about his appointment of Chief Justice Earl Warren, who led the Supreme Court’s liberal decisions on civil rights and criminal procedure.

The following are some other factors that can influence presidents’ choices of Supreme Court nominees:See David Alistair Yalof, Pursuit of Justices: Presidential Politics and the Selection of Supreme Court Nominees (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 4–7 and 17.

- Senate composition. Whether the president’s party has a majority or a minority in the Senate is a factor. In 1990, when the Democrats had a majority, Republican President George H. W. Bush nominated the judicially experienced and reputedly ideologically moderate David H. Souter, who was easily approved.

- Timing. The closer to an upcoming presidential election the appointment occurs, the more necessary it is to appoint a highly qualified, noncontroversial figure acceptable to the Senate, or at least someone senators would be reluctant to reject. Otherwise, senators have an incentive to stall until after the election, when it may be too late to obtain confirmation.

- Public approval of the president. The higher the president’s approval ratings, the more nominating leeway the president possesses. But even presidents riding a wave of popularity can fail to get their nominees past the Senate, as was the case with Richard Nixon and his failed nominations of Clement Haynesworth and G. Harrold Carswell in 1970. So lacking were Carswell’s qualifications that a senator defended him saying “Even if he were mediocre, there are a lot of mediocre judges and people and lawyers. They are entitled to a little representation…and a little chance.”Warren Weaver Jr., “Carswell Nomination Attacked and Defended as Senate Opens Debate on Nomination,” New York Times, March 17, 1970, A11.

- Interest groups. Nominees must usually be acceptable to interest groups that support the president and invulnerable (or at least resistant) to being depicted negatively—for example, as ideological extremists—by opposition groups, in ways that would significantly reduce their chances of Senate approval.

Nominations go to the Senate Judiciary Committee, which usually holds hearings. Whether senators should concern themselves with anything more than the nominee’s professional qualifications is often debated. Arguably, “nothing in the Constitution, historical experience, political practice, ethical norms, or statutory enactments prohibits senators from asking questions that reveal judicial nominees’ views on political and ideological issues.”Albert P. Melone, “The Senate’s Confirmation Role in Supreme Court Nominations and the Politics of Ideology versus Impartiality,” Judicature 75, no. 2 (August–September 1991): 529; also Nancy Scherer, Scoring Points: Political Activists and the Lower Federal Court Confirmation Process (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005).

The next step is for the Judiciary Committee to vote on whether or not to send the nomination to the Senate floor. If it reaches the floor, senators then can vote to confirm or reject the nomination, or filibuster so that a vote is delayed or does not take place. Fewer than half of recent nominees to the federal appeals courts have been confirmed.Sarah A. Binder and Forrest Maltzman, Advice and Dissent: The Struggle to Shape the Federal Judiciary (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2009).

The Media and Supreme Court Nominees

Presidents have few opportunities to nominate Supreme Court justices, so the media provide intensive coverage of every stage of the nomination, from the time an incumbent justice leaves office until a replacement is confirmed by the Senate. The scrutiny is not necessarily damaging. President Clinton’s nominees, Ruth Bader Ginsberg and Stephen Breyer, enjoyed Senate confirmation by votes of 97–3 and 87–9, respectively.

Sometimes the media determine a nominee’s fate. President Reagan’s nominee Douglas H. Ginsburg withdrew when news stories reported that he had smoked marijuana with some of his Harvard Law School students. The media were also intimately involved with the fates of Robert H. Bork and Clarence Thomas, particularly through their coverage of the Senate Judiciary Committee’s hearings.

The Failed Nomination of Robert H. Bork

Bork was a distinguished lawyer who had taught at Yale University, served as solicitor general and acting attorney general of the United States, and was a judge on the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit. He opposed civil rights laws and such Supreme Court decisions as Roe v. Wade allowing abortion. More than three hundred, mostly liberal, interest groups publicly opposed him.

The anti-Bork coalition adroitly used the media against him. It barraged two thousand journalists and seventeen hundred editorial writers with detailed packets of material criticizing him. It sponsored television and newspaper advertisements attacking him and asking Americans to urge their senators to vote against him.Michael Pertschuk and Wendy Schaetzel, The People’s Rising (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1989), 155; also Ethan Bronner, Battle for Justice: How the Bork Nomination Shook America (New York: Norton, 1989).

Figure 15.5 Robert Bork with President Reagan

Self-confident at his public nomination by President Reagan, Bork would be defeated by the campaign waged against him by his opponents.

The nominee, touted by his supporters as urbane, witty, and brilliant, contributed to his demise by the impression he made on national television during five contentious days, during which he candidly testified about his legal and political philosophy, defended his views on issues and cases, and responded to questions from members of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Having refused the practice sessions (known as “murder boards”Sessions in which nominees for the Supreme Court are coached by administration officials on how to respond successfully to tough questions from senators at their hearings.) and coaching offered by the White House, the professorial, scraggly bearded Bork was outmaneuvered by his opponents on the committee, who came up with such sound bites—featured on the evening television news—as, “You are not a frightening man, but you are a man with frightening views.”Senator Howard Metzenbaum (D.-Ohio), cited in Mark Gitenstein, Matters of Principle (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), 239.

The Senate rejected the nominee on October 23, 1987, by a vote of 58–42. The process generated a new verb in politics: “to bork,”To defeat a Supreme Court nominee by means of a lobbying and public relations campaign using and facilitated by the media. which means to unleash a lobbying and public relations campaign, using and facilitated by the media.

Link

The Bork Hearings

Watch video of the Bork hearings online at http://www.c-spanarchives.org/program/994-2&showFullAbstract=1.

The Successful Nomination of Clarence Thomas

When a similar attack was waged against Clarence Thomas in the fall of 1991, the White House and the nominee’s defenders were ready with a highly organized public relations campaign.

President George H. W. Bush nominated Clarence Thomas for the seat of retiring Justice Thurgood Marshall. Both were African Americans. But in contrast to the liberal Democrat Marshall, Thomas was a conservative Republican. The nomination was opposed by leaders of liberal and feminist organizations, and supported by their conservative counterparts. It divided the civil rights community, which wanted an African American justice, but not one as conservative as Thomas.

Because the nomination was shrewdly announced on the Monday afternoon preceding the Fourth of July weekend, reporters had time to transmit only the favorable story, spoon-fed from the White House, of the nominee’s rise from poverty to prominence. Later, they reported some of his more controversial decisions during his one-year tenure as a federal appeals court judge.

News coverage of the nomination resumed with the Senate Judiciary Committee’s hearings during which Thomas, in contrast to Bork, steadfastly avoided taking clear stands on controversial issues. He had been advised by his White House advisors to “(1) stress his humble roots; (2) [not] engage Senators in ideological debate; and (3) stonewall on abortion.”Mark Gitenstein, Matters of Principle (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), 337. At the conclusion of the hearings, Senate confirmation seemed narrowly assured. Then law professor Anita Hill accused Thomas of having engaged in sexual improprieties when she worked for him at the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

With the salacious accusations, media coverage skyrocketed, especially when the hearings reopened featuring Hill’s testimony and Thomas’s rebuttals. Entertainment media made light of the issue: on Saturday Night Live, Chris Rock observed that “if Clarence Thomas looked like Denzel Washington this thing would never have happened.” Thomas angrily accused his detractors of attempting “a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks.” In the end, most senators voted as they had been leaning prior to Hill’s testimony. Thomas was confirmed by a vote of 52–48.

Link

The Thomas Hearings

Watch the Thomas hearings online at http://www.c-spanarchives.org/program/Day1Part1.

Nomination of John G. Roberts Jr.

In July 2005, President George W. Bush made the first Supreme Court nomination in eleven years. He chose John G. Roberts Jr., a federal appeals court judge on the DC Circuit, to replace the moderate Republican Sandra Day O’Connor, who was retiring. Roberts was then nominated to be chief justice after the death of incumbent William H. Rehnquist.

Figure 15.6

The media’s intense attention to Supreme Court nominees is caught in this photograph showing the gaggle of journalists around John G. Roberts as he meets with the president.

Source: Photo courtesy of the White House (Paul Morse), http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Johnroberts3.jpeg.

During three days of testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee, the erudite and engaging Roberts deflected questions by comparing judges to umpires and saying that he would be guided by the law. On September 29, 2005, the Republican-controlled Senate approved him as chief justice of the US Supreme Court by a vote of 78–22.

Link

John G. Roberts’ Opening Statement

Watch the opening statement of John G. Roberts online at http://www.c-spanclassroom.org/Video/44/Judge+John+Roberts+Opening+Statement+at+Confirmation+Hearing+for+US+Chief+Justice.aspx.

Nominations of Harriet Miers and Samuel A. Alito Jr.

Bush next turned to fill Sandra Day O’Connor’s vacant seat. He was under pressure, even in public statements from his wife, to appoint a woman to succeed O’Connor. He nominated his White House general counsel and close friend, Harriet Miers. She had never served as a judge, had little expertise on constitutional matters, and held few reported positions on important issues.

Conservatives, including officeholders, interest-group leaders, columnists, pundits, and bloggers, rejected the president’s assurance that she was a candidate they could trust. Leaders of the Senate Judiciary Committee rejected her answers to their questions as “inadequate, insufficient and insulting.” Senators expressed doubts to the news media about her qualifications and knowledge of the Constitution. After twenty-four days of a ferocious barrage of criticism, all reported and amplified by the media, Ms. Miers withdrew from consideration.

President Bush then nominated a federal appeals court judge, Samuel A. Alito Jr. The judge had a record from his time in the Reagan administration and from fifteen years of judicial decisions of deferring to the executive branch, favoring business, and rejecting abortion rights.

In testifying before the members of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Judge Alito followed the stonewalling script. Nothing he said could be used against him by Democratic senators on the committee or by the media. A dramatic moment in his favor, shown on television, occurred when his wife, upset by the questioning directed at him, walked out of the hearings in tears. Soon after the hearings, Judge Alito was approved by 58–42 (54 Republicans plus 4 Democrats against 40 Democrats plus 1 Republican and 1 Independent).

Link

The Miers Nomination

Learn more about the Miers nomination online at http://www.npr.org/series/4933926/harriet- miers-withdraws-as-high-court-nominee.

Learn more about the Alito nomination online at http://www.npr.org/series/4982475/alito-s- supreme-court-nomination-confirmed.

Nominations of Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan

When Justice Souter resigned from the Court, President Obama, making his first nomination, picked Sonia Sotomayor to replace him. Her confirmation hearings in July 2009 followed the script that had worked for Roberts and Alito. She refused to opine about cases or identify a judicial philosophy other than “fidelity to the law.” Sotomayor would be the first Hispanic and third woman ever appointed to the Court. She would not change its ideological balance, and there were no media revelations to derail her prospects. Since the Democrats had sixty votes in the Senate, it came as no surprise that she was confirmed by a vote of 68–31.

A similar pattern followed the resignation of Justice John Paul Stevens. Obama’s nominee, Solicitor General and former Dean of the Harvard Law School Elena Kagan, was unlikely to change the ideological balance on the Court. She, too, largely stonewalled the hearings and was confirmed by the Senate on August 5, 2010, by a vote of 63–37.

Link

The Sotomayor Nomination

Learn more about the Sotomayor nomination online at http://www.npr.org/series/106462774/sonia- sotomayor-s-supreme-court-nomination.

Learn more about the Kagan nomination online at http://www.npr.org/series/126664425/elena- kagan-s-supreme-court-nomination.

Key Takeaways

Presidents usually look to nominate as federal judges people who share their ideological, policy, and partisan views. Nominations attract intense scrutiny from interest groups and the media and can be controversial and contentious. They are subject to confirmation by the Senate, which may delay, block, or approve them. We explain why the nominations of Robert H. Bork and Harriet Miers failed and why those of Clarence Thomas, John G. Roberts Jr., Samuel A. Alito Jr., Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan were successful.

Exercises

- What qualities do you think are important in Supreme Court justices? Do you think the confirmation process is a good way of selecting justices?

- How does public opinion affect who gets appointed to the Supreme Court? What role do you think public opinion should play?

- Imagine you were helping prepare a nominee for the nominations process. What advice would you give?

15.4 The Courts in the Information Age

Learning Objectives

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How do Supreme Court justices interact with the media?

- How do reporters go about covering the Supreme Court?

- How are the Supreme Court and its decisions depicted in the information age?

- What are the consequences of these depictions?

Media Interactions

Occasionally, Supreme Court justices give speeches about broad constitutional issues, talk off the record with a journalist, or rarely, engage in an on-the-record interview.An exception was Justice William J. Brennan Jr., who, in 1986, engaged in sixty hours of candid interviews with reporter Stephen Wermiel and allowed him to go through his papers. The agreement was that, after Brennan retired, the reporter would write his biography. Brennan retired in 1990. The book finally appeared in 2010: Sol Stern and Stephen Wermiel, Justice Brennan: Liberal Champion (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010). They may write a book setting forth their judicial philosophies and go on television to publicize it.Antonin Scalia, with replies by scholars, A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998); also Stephen G. Breyer, Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution (New York: Knopf, 2005). Justice Stephen Breyer appeared on Larry King Live to promote his latest book. He was circumspect, carefully avoiding discussing cases in any detail or revealing the Court’s deliberations.Stephen G. Breyer, Making Our Democracy Work: A Judge’s View (New York: Knopf, 2010); the interview was on September 15, 2010.

The more flamboyant Justice Antonin Scalia has appeared on 60 Minutes to promote a book he coauthored on how to persuade judges. During the interview, he did discuss some of his views.April 27, 2008; the book is Antonin Scalia and Bryan Garner, Making Your Case: The Art of Persuading Judges (Eagan, MN: Thomson West, 2008). Also, he does not shy away from voicing controversial opinions in statements and speeches, saying, for example, “you would have to be an idiot” to believe that the Constitution is a living document.Justice Scalia appeared on the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) panel on the state of civil liberties televised by C-SPAN (October 15, 2006), explaining and defending some of his decisions. (Watch the Scalia interview online at http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2008/04/24/60minutes/main4040290.shtml.) Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, in a speech that could be seen as a response and that was posted on the Court’s website, expressed her preference for “dynamic” over “static, frozen-in-time constitutional interpretation.”Adam Liptak, “Public Comments by Justices Veer Toward the Political,” New York Times, March 19, 2006, 22.

Withal, most judges shun the media. They rarely hold press conferences or discuss current cases.Our discussion of interactions draws from Richard Davis, Decisions and Images: The Supreme Court and the Press (New York: Prentice Hall, 1994); also Robert E. Drechsel, News Making in the Trial Courts (New York: Longman, 1983). Toni House, who served as the Supreme Court’s public information officer for many years, described her job as “peculiar in Washington because this office doesn’t spin, it doesn’t flap, it doesn’t interpret…When an opinion comes down, we put it in the hands of a reporter.”Quoted in Elliot E. Slotnick and Jennifer A. Segal, Television News and the Supreme Court (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 33–34. Nowadays, the court does frequently release audio of the oral arguments.

The main way in which justices communicate with the media is through the legal language of their written opinions. Even when a case is controversial and the Supreme Court is divided 5–4, the justices use such language in their opinions to justify their decisions. No matter how impassioned, this legal language makes it difficult for reporters to raise the subjects of partisanship or politics when writing stories about the Court’s actions.

Majesty and Secrecy

The justices have two powerful weapons that help them present to the public an image of themselves as above politics and partisanship: majesty and secrecy.

Figure 15.7 US Supreme Court Building

The Supreme Court building: so magisterial and redolent of justice achieved away from the hurly-burly of politics.

© Thinkstock

Majesty begins with the Supreme Court building, which commands awe and respect. It continues with what reporters see inside the courtroom—all that they see—which is designed to elevate the justices and the judicial process to a magisterial and impersonal status: the ornate setting, the ritual, the ceremony, the justices presiding in their robes, seated on high-backed chairs, physically and metaphorically raised up. This effect is conveyed most visibly in the official photograph of the nine justices (Note 15.41 "Enduring Image").

Enduring Image

Photos of the Supreme Court Justices

The traditional group photograph that the members of the Supreme Court allow to be taken shows them arrayed and authoritative in their impressive institutional setting. This enduring image enhances the justices’ standing and contributes to people’s acceptance of their rulings.

Official Photo of the Supreme Court Justices

Source: Photo courtesy of Steve Petteway, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United Stateshttp://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Supreme_Court_US_2010.jpg.

But what if they were shown discussing cases as bargainers? Or engaged in a nonjudicial activity? Or caught in an embarrassing moment in the way that celebrities are trapped by the tabloids? Such photographs would detract from the justices’ authority and the Court’s legitimacy.

Note the furor provoked by America (The Book)Jon Stewart, America (The Book) (New York: Warner Brothers, 2004). by Jon Stewart and the writers of The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. Wal-Mart refused to stock it. The reason: one page of this parody of a civics textbook shows the faces of the Supreme Court justices superimposed over naked elderly bodies. The facing page has cutouts of the justices’ robes and a caption asking readers to “restore their dignity by matching each justice with his or her respective robe.”

The second way in which judges obtain favorable media coverage is through secrecy. Denied to reporters—and therefore absent from the news—are the justices’ discussions on granting review, conference proceedings, and the process of creating a majority through opinion writing. The press is not privy to the decision-making processes, the informal contacts among the justices, the appeals and persuasion, the negotiation and bargaining, and the sometimes pragmatic compromises.When he retired in 1994, Justice Harry Blackman gave his papers to the Library of Congress on the condition that they remained closed for five years.

Cameras in the Courtroom

Cameras are prohibited in the Supreme Court during public sessions. The stated reasons for the ban are that it prevents lawyers and justices from playing to the cameras and avoids any physical disruption of the chamber. There is also concern that news coverage would emphasize the brief oral arguments, which can be misleading—since the essence of appellate advocacy before the Court is in the written briefs. The unstated reasons are that cameras might not only cause the justices to lose their cherished anonymity and privacy but also undermine the Court’s mystique by allowing people to see and judge the justices’ behavior.

Television cameras are excluded from most other federal courts for many of the same reasons. They are allowed in all state courts under conditions and restrictions, for example, consent of the judge, agreement of the attorneys for both sides, fixed placement, and a prohibition against showing jurors.

Reporters

Reporters covering the Supreme Court tend to be protective of the institution and the justices. In part, this is because they see law and politics as separate and different. Also, they do not have access to the kind of behavior and information that might lead them to think of and frame the Court in terms of policy and, particularly, politics.

Even when reporters at the Court are familiar with the facts and the oral arguments and have read the briefs of cases, they have more than enough to do just summarizing the justices’ decisions. These decisions can be complex, containing fifty to a hundred or more pages of dense text, often with detailed concurring and dissenting opinions. At its busiest time of the year, the Court releases several opinions at once; over 40 percent are issued during the last three weeks of the Court’s term. Reporters have little time to check over the cases and opinions, decide which ones are important, and prepare a report in layperson’s language.

On controversial cases, reporters are bombarded by reactions and analyses from the parties to the case, their attorneys, legal experts, and interest groups. Most of these people are usually available on the plaza in front of the Supreme Court, where microphones are set up for them.

Figure 15.8 Supreme Court Plaza

After a controversial Supreme Court decision, reporters can interview the attorneys, their clients, and interest-group spokespersons.

Source: Photo courtesy of dbking, http://www.flickr.com/photos/bootbearwdc/22009192/.

Reporters may include some of these views in their stories and show that the justice’s decisions have effects on people’s lives. But they usually lack the time and space to explain the decisions in explicitly political terms.

Media Depictions of the Supreme Court

After the acrimony of Bush v. Gore, the four dissenting justices returned to collegiality. Media and public discussion of the decision as partisan politics died down. The authority and legitimacy of the Court and the justices were reaffirmed.

Apolitical Coverage

Contributing to the return to normalcy, the media usually depict the Supreme Court as apoliticalAbove and beyond politics and partisanship., that is, above and beyond politics and partisanship.