This is “Stakeholders”, section 4.5 from the book Management Principles (v. 1.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

4.5 Stakeholders

Learning Objectives

- Learn about stakeholders and their importance.

- Understand stakeholder analysis.

- Be able to map stakeholders and their level of participation.

Figure 4.9

Government tends to be a key stakeholder for every organization.

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Stakeholders and Stakeholder Analysis

StakeholdersIndividuals and organizations who are actively involved in the organization, or whose interests may be positively or negatively affected as a result of what the organization does. are individuals or groups who have an interest in an organization’s ability to deliver intended results and maintain the viability of its products and services. We’ve already stressed the importance of stakeholders to a firm’s mission and vision. We’ve also explained that firms are usually accountable to a broad range of stakeholders, including shareholders, who can make it either more difficult or easier to execute a strategy and realize its mission and vision. This is the main reason managers must consider stakeholders’ interests, needs, and preferences.

Considering these factors in the development of a firm’s mission and vision is a good place to start, but first, of course, you must identify critical stakeholders, get a handle on their short- and long-term interests, calculate their potential influence on your strategy, and take into consideration how the firms strategy might affect the stakeholders (beneficially or adversely). Table 4.2 "Stakeholder Categories" provides one way to begin thinking about the various stakeholder groups, their interests, importance, and influence. InfluenceA stakeholder’s relative power over and within an organization. reflects a stakeholder’s relative power over and within an organization; importanceThe degree to which the organization cannot be considered successful if a stakeholder’s needs, expectations, and issues are not addressed. indicates the degree to which the organization cannot be considered successful if a stakeholder’s needs, expectations, and issues are not addressed.

Table 4.2 Stakeholder Categories

| Stakeholder | Categories | Interests | Importance | Influence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owners | ||||

| Managers | ||||

| Employees | ||||

| Customers | ||||

| Environmental | ||||

| Social | ||||

| Government | ||||

| Suppliers | ||||

| Competitors | ||||

| Other? |

Adapted from http://www.stsc.hill.af.mil/crosstalk/2000/12/smith.html.

As you can imagine, for instance, one key stakeholder group comprises the CEO and the members of the top-management team. These are key managers, and they might be owners as well. This group is important for at least three reasons:

- Its influence as either originator or steward of the organization’s mission and vision.

- Its responsibility for formulating a strategy that realizes the mission and vision.

- Its ultimate role in strategy implementation.

Typically, stakeholder evaluation of both quantitative and qualitative performance outcomes will determine whether management is effective. Quantitative outcomes include stock price, total sales, and net profits, while qualitative outcomes include customer service and employee satisfaction. As you can imagine, different stakeholders may place more emphasis on some outcomes than other stakeholders, who have other priorities.

Stakeholders, Mission, and Vision

Stakeholder analysisThe range of techniques or tools used to identify and to understand the needs and expectations of major interests inside and outside the organization environment. refers to the range of techniques or tools used to identify and understand the needs and expectations of major interests inside and outside the organization environment. Managers perform stakeholder analysis to gain a better understanding of the range and variety of groups and individuals who not only have a vested interest in the organization, and ultimately the formulation and implementation of a firm’s strategy, but who also have some influence on firm performance. Managers thus develop mission and vision statements, not only to clarify the organization’s larger purpose but also to meet or exceed the needs of its key stakeholders.

Stakeholder analysis may also enable managers to identify other parties that might derail otherwise well-formulated strategies, such as local, state, national, or foreign governmental bodies. Finally, stakeholder analysis enables organizations to better formulate, implement, and monitor their strategies, and this is why stakeholder analysis is a critical factor in the ultimate implementation of a strategy.

Identifying Stakeholders

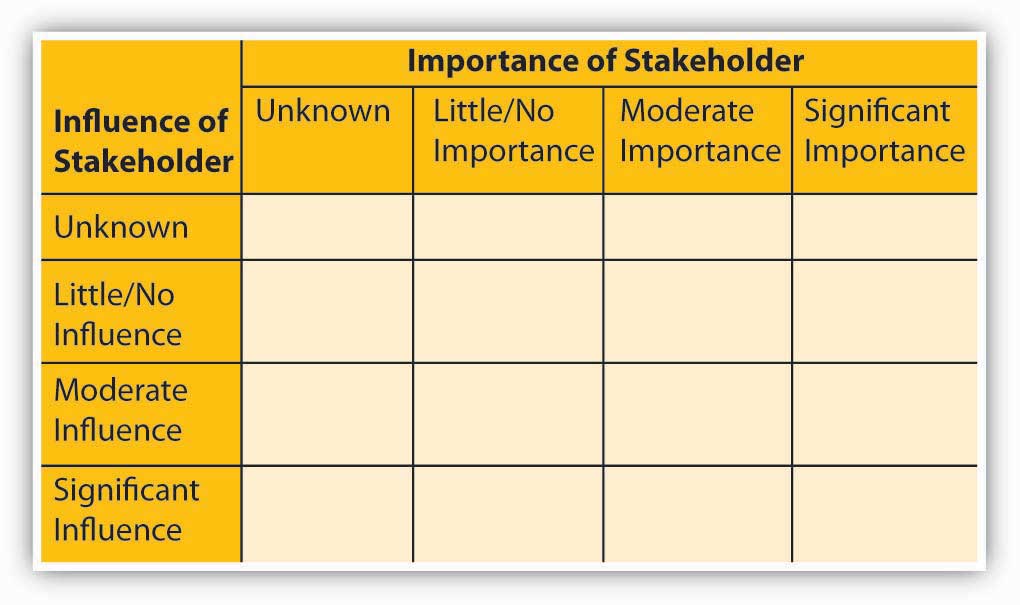

The first step in stakeholder analysis is identifying major stakeholder groups. As you can imagine, the groups of stakeholders who will, either directly or indirectly, be affected by or have an effect on a firm’s strategy and its execution can run the gamut from employees, to customers, to competitors, to the government. Ultimately, we will want to take these stakeholders and plot them on a chart, similar to that shown in the following figure.

Figure 4.10 Stakeholder Mapping

Adapted from Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman.

Let’s pause for a moment to consider the important constituencies we will be charting on our stakeholder map. Before we start, however, we need to remind ourselves that stakeholders can be individuals or groups—communities, social or political organizations, and so forth. In addition, we can break groups down demographically, geographically, by level and branch of government, or according to other relevant criteria. In so doing, we’re more likely to identify important groups that we might otherwise overlook.

With these facts in mind, you can see that, externally, a map of stakeholders will include such diverse groups as governmental bodies, community-based organizations, social and political action groups, trade unions and guilds, and even journalists. National and regional governments and international regulatory bodies will probably be key stakeholders for global firms or those whose strategy calls for greater international presence. Internally, key stakeholders include shareholders, business units, employees, and managers.

Steps in Identifying Stakeholders

Identifying all of a firm’s stakeholders can be a daunting task. In fact, as we will note again shortly, a list of stakeholders that is too long actually may reduce the effectiveness of this important tool by overwhelming decision makers with too much information. To simplify the process, we suggest that you start by identifying groups that fall into one of four categories: organizational, capital market, product market, and social. Let’s take a closer look at this step.

Step 1: Determining Influences on Mission, Vision, and Strategy Formulation. One way to analyze the importance and roles of the individuals who compose a stakeholder group is to identify the people and teams who should be consulted as strategy is developed or who will play some part in its eventual implementation. These are organizational stakeholders, and they include both high-level managers and frontline workers. Capital-market stakeholders are groups that affect the availability or cost of capital—shareholders, venture capitalists, banks, and other financial intermediaries. Product-market stakeholders include parties with whom the firm shares its industry, including suppliers and customers. Social stakeholders consist broadly of external groups and organizations that may be affected by or exercise influence over firm strategy and performance, such as unions, governments, and activist groups. The next two steps are to determine how various stakeholders are affected by the firm’s strategic decisions and the degree of power that various stakeholders wield over the firm’s ability to choose a course of action.

Step 2: Determining the Effects of Key Decisions on the Stakeholder. Step 2 in stakeholder analysis is to determine the nature of the effect of the firm’s strategic decisions on the list of relevant stakeholders. Not all stakeholders are affected equally by strategic decisions. Some effects may be rather mild, and any positive or negative effects may be secondary and of minimal impact. At the other end of the spectrum, some stakeholders bear the brunt of firm decisions, good or bad.

In performing step 1, companies often develop overly broad and unwieldy lists of stakeholders. At this stage, it’s critical to determine the stakeholders who are most important based on how the firm’s strategy affects the stakeholders. You must determine which of the groups still on your list have direct or indirect material claims on firm performance or which are potentially adversely affected. For instance, it is easy to see how shareholders are affected by firm strategies—their wealth either increases or decreases in correspondence with the firm’s actions. Other parties have economic interests in the firm as well, such as parties the firm interacts with in the marketplace, including suppliers and customers. The effects on other parties may be much more indirect. For instance, governments have an economic interest in firms doing well—they collect tax revenue from them. However, in cities that are well diversified with many employers, a single firm has minimal economic impact on what the government collects. Alternatively, in other areas, individual firms represent a significant contribution to local employment and tax revenue. In those situations, the effect of firm actions on the government would be much greater.

Step 3: Determining Stakeholders’ Power and Influence over Decisions. The third step of a stakeholder analysis is to determine the degree to which a stakeholder group can exercise power and influence over the decisions the firm makes. Does the group have direct control over what is decided, veto power over decisions, nuisance influence, or no influence? Recognize that although the degree to which a stakeholder is affected by firm decisions (i.e., step 2) is sometimes highly correlated with their power and influence over the decision, this is often not the case. For instance, in some companies, frontline employees may be directly affected by firm decisions but have no say in what those decisions are. Power can take the form of formal voting power (boards of directors and owners), economic power (suppliers, financial institutions, and unions), or political power (dissident stockholders, political action groups, and governmental bodies). Sometimes the parties that exercise significant power over firm decisions don’t register as having a significant stake in the firm (step 2). In recent years, for example, Wal-Mart has encountered significant resistance in some communities by well-organized groups who oppose the entry of the mega-retailer. Wal-Mart executives now have to anticipate whether a vocal and politically powerful community group will oppose its new stores or aim to reduce their size, which decreases Wal-Mart’s per store profitability. Indeed, in many markets, such groups have been effective at blocking new stores, reducing their size, or changing building specifications.

Once you’ve determined who has a stake in the outcomes of the firm’s decisions as well as who has power over these decisions, you’ll have a basis on which to allocate prominence in the strategy-formulation and strategy-implementation processes. The framework in the figure will also help you categorize stakeholders according to their influence in determining strategy versus their importance to strategy execution. For one thing, this distinction may help you identify major omissions in strategy formulation and implementation.

Having identified stakeholder groups and differentiated them by how they are affected by firm decisions and the power they have to influence decisions, you’ll want to ask yourself some additional questions:

- Have I identified any vulnerable points in either the strategy or its potential implementation?

- Which groups are mobilized and active in promoting their interests?

- Have I identified supporters and opponents of the strategy?

- Which groups will benefit from successful execution of the strategy and which may be adversely affected?

- Where are various groups located? Who belongs to them? Who represents them?

The stakeholder-analysis framework summarized in the figure is a good starting point. Ultimately, because mission and vision are necessarily long term in orientation, identifying important stakeholder groups will help you to understand which constituencies stand to gain or to lose the most if they’re realized.

Two Challenges

Two of the challenges of performing stakeholder analysis are determining how stakeholders are affected by a firm’s decisions and how much influence they have over the implementation of the decisions that are made. Many people have a tendency to fall into the trap of assessing all stakeholders as being important on both dimensions. In reality, not all stakeholders are affected in the same way and not all stakeholders have the same level of influence in determining what a firm does. Moreover, when stakeholder analysis is executed well, the resulting strategy has a better chance of succeeding, simply because the entities you might rely on in the implementation phase were already involved in the strategy starting with the formulation phase. Thus, you now have a good idea of how to engage various stakeholders in all the stages of the P-O-L-C framework.

Key Takeaway

This section introduced stakeholders, their roles, and how to begin assessing their roles in the development of the organization’s mission and vision. While any person or organization with a stake in your organization is a stakeholder, managers are most concerned with those stakeholders who have the most influence on, or will be most influenced by, the organization. On the basis of your assessment of stakeholders, you now can be proactive in involving them in the P-O-L-C stages.

Exercises

- What are stakeholders, and why are they relevant to mission and vision?

- Are stakeholders equally relevant to all parts of P-O-L-C, or only mission and vision?

- What is stakeholder analysis? What are the three identification steps?

- How does stakeholder analysis help you craft a mission and vision statement?

- Which important stakeholders might you intentionally exclude from a mission or vision statement?

- What are the risks of not conducting stakeholder analysis as an input to the formulation of your mission and vision?